Gertrude Barrows Bennett

| Gertrude Barrows Bennett | |

|---|---|

| Born |

Gertrude Mabel Barrows 1883 Minneapolis |

| Died | 1948 |

| Pen name | Francis Stevens |

| Occupation | Writer, stenographer |

| Nationality | American |

| Period | 1917–26 (fiction writer) |

| Genre | Science fiction, fantasy |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse | Stewart Bennett |

Gertrude Barrows Bennett (1883–1948) was the first major female writer of fantasy and science fiction in the United States, publishing her stories under the pseudonym Francis Stevens.[1] Bennett wrote a number of highly acclaimed fantasies between 1917 and 1923[2] and has been called "the woman who invented dark fantasy".[3]

Her most famous books include Claimed (which Augustus T. Swift, in a letter to The Argosy called "One of the strangest and most compelling science fantasy novels you will ever read")[lower-alpha 1] and the lost world novel The Citadel of Fear.

Bennett also wrote an early dystopian novel, The Heads of Cerberus (1919).[2]

Life

Gertrude Mabel Barrows was born in Minneapolis in 1883. She completed school through the eighth grade,[1] then attended night school in hopes of becoming an illustrator (a goal she never achieved). Instead, she began working as a stenographer, a job she held on and off for the rest of her life.[5]

In 1909 Barrows married Stewart Bennett, a British journalist and explorer, and moved to Philadelphia.[1] A year later her husband died while on an expedition. With a new-born daughter to raise, Bennett continued working as a stenographer. When her father died toward the end of World War I, Bennett assumed care for her invalid mother.[1]

During this time period Bennett began to write a number of short stories and novels, only stopping when her mother died in 1920.[5] In the mid-1920s, she moved to California. Because Bennett was estranged from her daughter, for a number of years researchers believed Bennett died in 1939 (the date of her final letter to her daughter). However, new research, including her death certificate, shows that she died in 1948.[5]

Writing career

Bennett wrote her first short story at age 17, a science fiction story titled "The Curious Experience of Thomas Dunbar". She mailed the story to Argosy, then one of the top pulp magazines. The story was accepted and published in the March 1904 issue.[1]

Once Bennett began to take care of her mother, she decided to return to fiction writing as a means of supporting her family.[1] The first story she completed after her return to writing was the novella "The Nightmare," which appeared in All-Story Weekly in 1917. The story is set on an island separated from the rest of the world, on which evolution has taken a different course. "The Nightmare" resembles Edgar Rice Burroughs' The Land That Time Forgot, itself published a year later.[1] While Bennett had submitted "The Nightmare" under her own name, she had asked to use a pseudonym if it was published. The magazine's editor chose not to use the pseudonym Bennett suggested (Jean Vail) and instead credited the story to Francis Stevens.[1] When readers responded positively to the story, Bennett chose to continue writing under the name.[1]

Over the next few years, Bennett wrote a number of short stories and novellas. Her short story "Friend Island" (All-Story Weekly, 1918), for example, is set in a 22nd-century ruled by women. Another story is the novella "Serapion" (Argosy, 1920), about a man possessed by a supernatural creature. This story has been released in an electronic book entitled Possessed: A Tale of the Demon Serapion, with three other stories by her. Many of her short stories have been collected in The Nightmare and Other Tales of Dark Fantasy (University of Nebraska Press, 2004).[6]

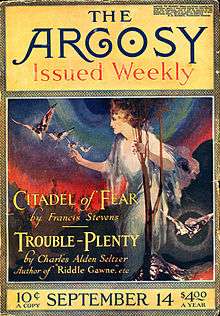

In 1918 she published her first, and perhaps best,[7] novel The Citadel of Fear (Argosy, 1918). This lost world story focuses on a forgotten Aztec city, which is "rediscovered" during World War I.[8][9] It was in the introduction to a 1952 reprint edition of the novel which revealed for the first time that "Francis Stevens" was Bennett's pen-name.

A year later she published her only science fiction novel, The Heads of Cerberus (The Thrill Book, 1919). One of the first dystopian novels, the book features a "grey dust from a silver phial" which transports anyone who inhales it to a totalitarian Philadelphia of 2118 AD[2]

One of Bennett's most famous novels was Claimed (Argosy, 1920; reprinted 1966 and 2004), in which a supernatural artifact summons an ancient and powerful god to 20th century New Jersey.[8][10] Augustus T. Swift called the novel, "One of the strangest and most compelling science fantasy novels you will ever read").[lower-alpha 1]

Influence

Bennett has been credited as having "the best claim at creating the new genre of dark fantasy".[3] It has been said that Bennett's writings influenced both H. P. Lovecraft and A. Merritt,[1] both of whom "emulated Bennett's earlier style and themes".[1][5] Lovecraft was even said to have praised Bennett's work. However, there is controversy about whether or not this actually happened and the praise appears to have resulted from letters wrongly attributed to Lovecraft.[11][12]

As for Merritt, for several decades critics and readers believed "Francis Stevens" was a pseudonym of his. This rumor only ended with the 1952 reprinting of Citadel of Fear, which featured a biographical introduction of Bennett by Lloyd Arthur Eshbach.[13]

Critic Sam Moskowitz said she was the "greatest woman writer of science fiction in the period between Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley and C.L. Moore".[1]

Because Bennett was the first American woman to have her fantasy and science fiction widely published, she has been recognized in recent years as a pioneering female fantasy author.[10]

Bibliography

Novels

- The Citadel of Fear (1918; reprinted in Famous Fantastic Mysteries, February 1942, and in paperback form in 1970,[NY: Paperback Library] and 1984[NY: Carroll & Graf])

- The Labyrinth (serialized in All-Story Weekly, July 27, August 3, and August 10, 1918; later reprinted as a paperback novel)

- The Heads of Cerberus 1st book edition. 1952, Cloth, also leather backed, Reading, PA. Polaris Press (Subsidiary of Fantasy Fress, Inc.) ill. Ric Binkley. Intro by Lloyd Arthur Eshbach (Thrill Book, 15 August 1919; reprinted as a paperback novel in 1952 and 1984)

- Avalon (serialized in Argosy, August 16 to September 6, 1919; not reprinted)

- Claimed (1920; reprinted in 1985, 1996, and 2004) 192pp, cloth and paper, Sense of Wonder Press, James A. Rock & Co., Publishers in trade paperback and hard cover.[4]

Short stories and novellas

- "The Curious Experience of Thomas Dunbar" (Argosy, March, 1904; as by G. M. Barrows)

- "The Nightmare," (All-Story Weekly, April 14, 1917)[14]

- "Friend Island" (All-Story Weekly, September 7, 1918; reprinted in Under the Moons of Mars, edited by Sam Moskowitz, 1970)

- "Behind the Curtain" (All-Story Weekly, September 21, 1918, reprinted in Famous Fantastic Mysteries, January 1940)

- "Unseen-Unfeared" (People's Favorite Magazine Feb. 10, 1919; reprinted in Horrors Unknown, edited by Sam Moskowitz, 1971)

- "The Elf-Trap" (Argosy, July 5, 1919)

- "Serapion" (serialized in Argosy Weekly, June 19, June 26, and July 3, 1920; reprinted in Famous Fantastic Mysteries, July 1942)

- "Sunfire" (1923; original printed in two parts in Weird Tales, July–August 1923, and Weird Tales, September 1923; also reprinted as trade paperback in 1996 by Apex International)

Collections

- Possessed: A Tale of the Demon Serapion (2002; contains the novella "Serapion", retitled, and the short stories "Behind the Curtain", "Elf-Trap" and "Unseen-Unfeared")

- Nightmare: And Other Tales of Dark Fantasy (University of Nebraska Press, 2004; contains all Stevens' known short fiction except "The Curious Experience of Thomas Dunbar", i.e. "The Nightmare", "The Labyrinth", "Friend Island", "Behind the Curtain", ""Unseen-Unfeared", "The Elf-Trap", "Serapion" and "Sunfire")

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Swift was at one time thought to be a pseudonym of H.P. Lovecraft but this has been proven spurious. He was a real individual in Providence. See the section Influence for more detail. Rock Publishing attributes the quotation to Lovecraft.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Partners in Wonder: Women and the Birth of Science Fiction, 1926-1965 by Eric Leif Davin, Lexington Books, 2005, pages 409-10.

- 1 2 3 Nicholls, Peter; Clute, John (1993). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. St. Martin's Press. pp. 1164–65. ISBN 0-312-13486-X..

- 1 2 "The Woman Who Invented Dark Fantasy" by Gary C. Hoppenstand from Nightmare and Other Tales of Dark Fantasy by Francis Stevens, University of Nebraska Press, 2004, page x. ISBN 0-8032-9298-8

- 1 2 (promotional page). ""Claimed"". James A. Rock and Company Publishers. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Woman Who Invented Dark Fantasy" by Gary C. Hoppenstand from Nightmare and Other Tales of Dark Fantasy by Francis Stevens, University of Nebraska Press, 2004, page xvi. ISBN 0-8032-9298-8

- ↑ Nightmare and Other Tales of Dark Fantasy by Francis Stevens, University of Nebraska Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8032-9298-8

- ↑ "The Woman Who Invented Dark Fantasy" by Gary C. Hoppenstand from Nightmare and Other Tales of Dark Fantasy by Francis Stevens, University of Nebraska Press, 2004, page xiii-xiv. ISBN 0-8032-9298-8

- 1 2 Survey of Modern Fantasy Literature by Frank Northen Magill, Salem Press, 1983, page 287.

- ↑ "The Woman Who Invented Dark Fantasy" by Gary C. Hoppenstand from Nightmare and Other Tales of Dark Fantasy by Francis Stevens, University of Nebraska Press, 2004, page xiv. ISBN 0-8032-9298-8

- 1 2 T. M. Wagner. "Review of Francis Steven's Claimed". SF reviews.net. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ↑ Women in Science Fiction and Fantasy edited by Robin Anne Reid, Greenwood, 2008, page 289.

- ↑ An H.P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia edited by S. T. Joshi, David E. Schultz, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, page 218.

- ↑ "Introduction to Citadel of Fear" by Lloyd Arthur Eshbach, Citadel of Fear by Francis Stevens, Polaris Press, 1952.

- ↑ Note: all short story information comes from "The Fiction Mags Index". Retrieved 2009-03-31.

Further reading

- R. Alain Everts. "The Mystery of Francis Stevens (1883–1948)". Outsider 4 (2000): 29–30.

- Bryce J. Stevens. "Into the Abyss: Did Francis Stevens' 1920 Novel Claimed Influence H.P. Lovecraft?". Presents textual evidence that Claimed may have influenced "The Call of Cthulhu".

- Sam Moskowitz. "The Woman Who Wrote 'Citadel of Fear'". The Citadel of Fear by Francis Stevens. NY: Paperback Library, 1970.

- Robert Weinberg. "A Forgotten Mistress of Fantasy". The Citadel of Fear by Francis Stevens. NY: Carroll & Graf, 1994.

External links

- Works by Francis Stevens at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Gertrude Barrows Bennett at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Francis Stevens at Manybooks.net

- Complete text of The Citadel of Fear (1918)

- Modern review of Claimed.

- Francis Stevens at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Francis Stevens at Library of Congress Authorities, with 4 catalog records