Gerald Durrell

| Gerald M. Durrell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

7 January 1925 Jamshedpur, British India |

| Died |

30 January 1995 (aged 70) Saint Helier, Jersey |

| Cause of death | Septicaemia |

| Known for | Founder of Jersey Zoo, author, television presenter, conservationist |

| Spouse(s) |

Jacquie Durrell (married 1951-79) Lee Durrell (married 1979) |

| Parent(s) | Lawrence Samuel Durrell and Louisa Dixie Durrell |

| Family | Lawrence (brother), Margaret (sister), Leslie Durrell (brother) |

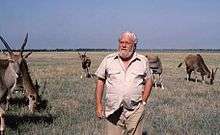

Gerald "Gerry" Malcolm Durrell, OBE (7 January 1925 – 30 January 1995) was a British naturalist, zookeeper, conservationist, author and television presenter. He founded what are now called the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust and the Durrell Wildlife Park on the Channel Island of Jersey in 1959. He wrote a number of books based on his life as an animal collector and enthusiast. He was the youngest brother of novelist Lawrence Durrell.

Early life and education

Durrell was born in Jamshedpur, India on 7 January 1925.[1] He was the fourth and final child of Louisa Florence Dixie and Lawrence Samuel Durrell, both of whom were born in India of English and Irish descent. Durrell's father was a British engineer and, as was commonplace and befitting the family status, the infant Durrell spent most of his time in the company of an ayah (nursemaid). Durrell reportedly recalled his first visit to a zoo in India and attributed his lifelong love of animals to that encounter.

The family moved to Britain shortly before the death of his father in 1928 and settled in the Upper Norwood, Crystal Palace area of South London.[2] Durrell was enrolled in Wickwood School, but frequently stayed at home feigning illness.[3]

Corfu

Mrs. Durrell moved with her three younger children (Leslie, Margaret and Gerald) to the Greek island of Corfu in 1935, joining her eldest son, Lawrence, who was living there with his wife. It was on Corfu that Durrell began to collect and keep the local fauna as pets.

The family lived on Corfu until 1939. This interval was later the basis of the book My Family and Other Animals and its successors, Birds, Beasts, and Relatives and The Garden of the Gods, plus a few short stories such as "My Donkey Sally". Durrell was home-schooled during this time by various family friends and private tutors, mostly friends of his eldest brother Lawrence (later to become a successful novelist).

Theodore Stephanides, a Greek doctor, scientist, poet, philosopher and a friend of one of Durrell's tutors, became Durrell's greatest friend and mentor, his ideas leaving a lasting impression on the young naturalist. Together, they examined Corfu's fauna, which Durrell housed in a variety of items including test tubes and bathtubs. Another major influence during these formative years, according to Durrell, was the writing of French naturalist Jean Henri Fabre.

London and Whipsnade Zoo

Gerald, his mother, his brother Leslie and their Greek maid Maria Kondos moved back to Britain in 1939 at the outbreak of the Second World War. It was difficult to find a job in the war and post-war years, especially for a home-schooled youth, but the enterprising Durrell worked as a helper at an aquarium and pet store. Some of the difficulties that he faced in this period can be found in Fillets of Plaice.

His call-up for the war came in 1943, but he was exempted from military duty on medical grounds, and asked to serve the war effort by working on a farm. After the war, Durrell joined Whipsnade Zoo as a junior or student keeper. This move fulfilled a lifelong dream: Durrell claims in The Stationary Ark that the first word that he could enunciate with any clarity was "zoo". Beasts in My Belfry recalls events of this period.

Early animal expeditions

Durrell left Whipsnade Zoo in May 1946 in order to join wildlife collecting expeditions of the time, but was denied a place in the voyages due to his lack of experience. Durrell's wildlife expeditions began with a 1947 trip to the British Cameroons (now part of Cameroon) with ornithologist John Yealland, financed by a £3,000 inheritance from his father on the occasion of his turning 21. The animals he brought back were sold to London Zoo, Chester Zoo, Paignton Zoo, Bristol Zoo and Belle Vue Zoo (Manchester). He continued such excursions for many decades, during which time he became famous for his work for wildlife conservation.

He followed this successful expedition with two others, accompanied by fellow Whipsnade zookeeper Ken Smith: a repeat trip to the British Cameroon, and to British Guiana (now Guyana) in 1949 and 1950 respectively. On the first of these trips, he met and befriended the shrewd and colourful Fon of Bafut Achirimbi II, an autocratic West African chieftain, who would help him organise future missions.

Because of his dedication, Durrell housed and fed his captives with the best supplies obtainable, never over-collecting specimens, never trapping animals having merely "show value", or those which would fetch high prices from collectors. These practices differed from those of other animal-collecting expeditions of the time and, as a result, Durrell was broke by the end of his third expedition. Further, due to a falling-out with George Cansdale, superintendent of the London Zoo, Durrell was blackballed by the British zoo community and could not secure a job in most zoos, ultimately securing a job at the aquarium at Belle Vue Zoo in Manchester where he remained for some time.

On 26 February 1951, after an extended courtship, Durrell married Manchester resident Jacqueline ('Jacquie') Sonia Wolfenden — they eloped, because of opposition from her father. The couple initially lived in a small bedsitter in Durrell's sister Margaret's Bournemouth boarding house. Jacquie accompanied Durrell on most of his following animal expeditions and helped found and manage the Jersey Zoo. She also authored two humorous, best-selling memoirs on the lines of Durrell's books, to raise money for conservation efforts.

With encouragement and assistance from Jacquie,[4] and advice from elder brother Lawrence, Gerald Durrell started writing humorous autobiographical accounts to raise money, initially because he and Jacquie were broke after their wedding and Durrell didn't have a source of income and then later to fund his expeditions and conservation efforts. His first book — The Overloaded Ark — was a huge success, causing Durrell to follow up with other such accounts. While Durrell only made £50 from British rights (Faber and Faber), he obtained £500 from the United States rights (Viking Press) for the book, and thus managed to raise money for a fourth expedition to South America in 1954. This, however, was undertaken during a political coup d'etat in Paraguay and was unsuccessful.

Foundations for the Jersey Zoo

The publication of My Family and Other Animals in 1956 made Durrell a notable author and brought him public recognition as a naturalist. Royalties from this book, which made best-seller lists in the United Kingdom,[5] helped to fund Durrell's next expedition.

Durrell's growing disillusionment with the way zoos of the time were run, and his belief that they should primarily act as reserves and regenerators of endangered species,[6] made him contemplate founding his own zoo. His 1957 trip to Cameroon for the third and last time was primarily to collect animals which would form the core collection of his own zoo.

This expedition was also filmed, it being Durrell's first experiment with making a cinematographic record of his work with animals. The success of the film To Bafut with Beagles, together with his autobiographical radio programme Encounters with Animals, made Durrell a regular with the BBC Natural History unit[7][8] for decades to come, as well as generating funds for his conservation projects.

On his return from Bafut, Durrell and wife Jacquie stayed with his sister Margaret at her boarding house in the seaside resort of Bournemouth. His animals were housed in her gardens and garage on a temporary basis, while Durrell sought prospective sites for a zoo.[9] To his dismay, both Bournemouth and Poole municipalities turned down his suggestion for a zoo. This experience provided material for his book A Zoo in My Luggage.

The Zoo and the Trust

Durrell founded the Jersey Zoological Park (now Durrell Wildlife Park) in 1959 to house his growing collection of animals. The site for the zoo, a 17th-century manor house, Les Augres Manor, came to Durrell's notice by chance after a long and unsuccessful search for a suitable site. Durrell leased the manor and set up his zoo on the redesigned manor grounds. In the same year, Durrell undertook another, more successful expedition to South America to collect endangered species. The zoo was opened to the public in 1959 on 26 March.

As the zoo grew in size, so did the number of projects undertaken to save threatened wildlife in other parts of the world. Durrell was instrumental in founding the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust (now Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust), on 6 July 1963 to cope with the increasingly difficult challenges of zoo, wildlife and habitat management.

The Trust opened an international wing, the Wildlife Preservation Trust International, in the United States in 1971, to aid international conservation efforts in a better fashion. That year, the Trust bought out Les Augres Manor from its owner, Major Hugh Fraser, giving the zoo a permanent home.

Durrell's initiative caused the Fauna and Flora Preservation Society to start the World Conference on Breeding Endangered Species in Captivity as an Aid to their Survival in 1972 at Jersey, today one of the most prestigious conferences in the field. 1972 also saw Princess Anne becoming a patron of the Trust, an action which brought the Trust into media limelight, and helped raise funds.

The 1970s saw Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust become a leading zoo in the field of captive breeding, championing the cause among species like the lowland gorilla, and various Mauritian fauna. Durrell visited Mauritius several times and coordinated large scale conservation efforts in Mauritius with conservationist Carl Jones, involving captive breeding programmes for native birds and reptiles, ecological recovery of Round Island, training local staff, and setting up local in-situ and ex-situ conservation facilities. This ultimately led to the founding of the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation in 1984.[10]

Jacquie Durrell separated from and then divorced Gerald Durrell in 1979, citing his increasing work pressure, associated alcoholism and mounting stress as causes.

Durrell met his second wife Lee McGeorge Durrell in 1977 when he lectured at Duke University, where she was studying for a PhD in animal communication. They married in 1979. She co-authored a number of books with him, including The Amateur Naturalist, and became the Honorary Director of the Trust after his death.

In 1978 Durrell started the training centre for conservationists at the zoo, or the "mini-university" in his words. As of 2005, over a thousand biologists, naturalists, zoo veterinarians and zoo architects from 104 countries have attended the International Training Centre. Durrell was also instrumental in forming the Captive Breeding Specialist Group of the World Conservation Union in 1982.

Durrell founded Wildlife Preservation Trust Canada, now Wildlife Preservation Canada, in 1985. The official appeal Saving Animals from Extinction was launched in 1991, at a time when British zoos were not faring well and London Zoo was in danger of closing down.

In 1989, Durrell and his wife Lee, along with David Attenborough and cricketer David Gower helped launch the World Land Trust (then the World Wide Land Conservation Trust). The initial goal of the trust was to purchase rainforest land in Belize as part of the Programme for Belize. Around this time Gerald Durrell developed a friendship with Charles Rycroft, who became an important donor of funds both for building works in Jersey (the Harcroft Lecture Theatre) and for conservation work in East Africa, Madagascar and elsewhere.

1990 saw the Trust establish a conservation programme in Madagascar along the lines of the Mauritius programme. Durrell visited Madagascar in 1990 to start captive breeding of a number of endemic species like the aye aye.

Durrell chose the dodo, the flightless bird of Mauritius that was hunted to extinction in the 17th century, as the logo for both the Jersey Zoo and the Trust. The children's chapter of the trust is called the Dodo Club. Following his death, the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust was renamed Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust at the 40th anniversary of the zoo on 26 March 1999. The Wildlife Preservation Trust International also changed its name to Wildlife Trust in 2000, and adopted the logo of the black tamarin.

To me, the (destruction) of an animal species is a criminal offence, in the same way as the destruction of anything we cannot recreate or replace, such as a Rembrandt [a famous painting] or the Acropolis (in Athens). (A Zoo in my Luggage)

Later life and death

A hard, outdoor life led Durrell to health problems in the 1980s. He underwent hip-replacement surgery in a bid to counter arthritis, but he also suffered from alcohol-related liver problems. His health deteriorated rapidly after the 1990 Madagascar trip. Durrell had a liver transplant in King's College Hospital on 28 March 1994,[11] and he died of septicaemia on 30 January 1995, shortly after his 70th birthday in Jersey General Hospital.[12] His ashes are buried in Jersey Zoo, under a memorial plaque bearing a quote by William Beebe.

The beauty and genius of a work of art may be re-conceived, though its first material expression be destroyed; a vanished harmony may yet again inspire the composer; but when the last individual of a race of living beings breathes no more, another heaven and another earth must pass before such a one can be again. (The Bird, 1906)

A memorial celebrating Durrell's life and work was held at the Natural History Museum in London on 28 June 1995. Participants included personal friends such as David Attenborough and Princess Anne.

Policy for zoos

Gerald Durrell was ahead of his time when he postulated the role that a 20th-century zoo should play, primarily in Stationary Ark. His idea relies on the following bases:

- The primary purpose of a zoo should be to act as a reserve of critically endangered species which need captive breeding in order to survive.

- They can serve the secondary purposes of educating people about wildlife and natural history, and of educating biologists about the animal's habits.

- Zoos should not be run for the purposes of entertainment only, and non-threatened species should be re-introduced into their natural habitats.

- An animal should be present in the zoo only as a last resort, when all efforts to save it in the wild have failed.

Durrell's ideas about housing zoo animals also bring his priorities to the fore. The bases on which enclosures at Jersey are built:

- Enclosures should be built keeping in mind — firstly, the comfort of the animal (including a private shelter), secondly for the convenience of the animal keeper, and finally for the viewing comfort of visitors.

- The size of an enclosure should depend on how large their territories might be.

- The companions of an animal should reflect not only ecological niche and biogeographic concerns, but its social abilities as well – how well it gets on with other members of its species and other species.

- Every animal deserves food of its choice, sometimes made interesting by variation; and a mate of its choice; and a nice and interesting environment.

Durrell Wildlife Park was the first zoo to house only endangered breeding species, and has been one of the pioneers in the field of captive breeding. The International Training Centre, and the organisation of the conference on captive breeding are also notable firsts.

Durrell initially faced stiff opposition and criticism from some members of the zoo community when he introduced the idea of captive breeding, and was only vindicated after successfully breeding a wide range of species. One of the most active opposition members was George Cansdale, superintendent of the London Zoo and Zoological Society of London, and wielder of considerable influence in the zoo community.

Books

Durrell's books, both fiction and non-fiction, have a wry, loose style that poked fun at himself as well as those around him. Perhaps his best-known work is My Family and Other Animals (1956), which tells of his idyllic, if oddball, childhood on Corfu. Later made into a TV series, it is delightfully deprecating about the whole family, especially elder brother Lawrence, who became a famous novelist. Despite Durrell's jokes at the expense of "brother Larry", the two were close friends all their lives.

Gerald Durrell always insisted that he wrote for royalties to help the cause of environmental stewardship, not out of an inherent love for writing. Gerald Durrell describes himself as a writer in comparison to his brother Lawrence:

The subtle difference between us is that he loves writing and I don't. To me it's simply a way to make money which enables me to do my animal work, nothing more.

However, he shows a surprising diversity and dexterity in a wide variety of writing, including:

- autobiographical accounts: Most of his works are of such kind — characterised by a love for nature and animals, dry wit, crisp descriptions and humorous analogies of human beings with animals and vice versa. The most famous of these is the Corfu trilogy — My Family and Other Animals, Birds, Beasts and Relatives, and The Garden of the Gods.

- short stories: often bordering on the Roald Dahl-esque, like "Michelin Man" in Picnic and Suchlike Pandemonium. The latter also has an acclaimed Gothic horror story titled "The Entrance". Marrying Off Mother and Other Stories also has a few short stories.

- novels: Durrell's only two novels for adults are Rosy is My Relative, a story about a bequeathed elephant which Durrell claimed is based on real life events, and The Mockery Bird, the fable based loosely on the story of Mauritius and the dodo.

- technical essays: The Stationary Ark is a collection of technical essays on zoo-keeping and conservation.

- guides: The Amateur Naturalist is the definitive guide for a budding naturalist over the last 20 years.

- novels for older children: The Donkey Rustlers is set on a Greek island, and The Talking Parcel is a tale of children at large in a land of mythological creatures.

- natural history books for children: The New Noah is a collection of encounters with animals from Durrell's previous expeditions, written with children in mind.

- stories for younger children: Keeper, Toby the Tortoise, The Fantastic Dinosaur Adventure and The Fantastic Flying Journey are lavishly illustrated stories.

- board and picture books: the board book series Puppy Stories are for infants, and the picture book Island Zoo is for young children about the first animals in Jersey Zoo.

Durrell was also a regular contributor to magazines on both sides of the Atlantic like Harper's, Atlantic Monthly and the Sunday Times Supplement. He was also a regular book reviewer for the New York Times. A number of excerpts and stories from his books were used by Octopus Books and Reader's Digest Publishing, including in the Reader's Digest Condensed Books.

Durrell's works have been translated into 31 languages, and made into TV serials and feature films. He has a large followings in Northern and Eastern Europe, Russia, Israel and in various Commonwealth countries, including India.

The British Library houses a collection of Durrell's books, presented by him to Alan G. Thomas, as part of the Lawrence Durrell Collection.

Illustrators

Durrell was a talented artist and caricaturist, but worked with numerous illustrators over the years starting with Sabine Baur for The Overloaded Ark (published by Faber and Faber). Two of his most productive collaborations were with Ralph Thompson (Bafut Beagles, Three Singles To Adventure, The New Noah, The Drunken Forest, Encounters with Animals, A Zoo in My Luggage, The Whispering Land, Menagerie Manor) (published by Rupert Hart-Davis) and Edward Mortelmans (Catch Me A Colobus, Beasts in My Belfry, Golden Bats and Pink Pigeons) (published by Collins). The illustrations are mostly sketches of animal subjects. Ralph Thompson visited the Jersey Zoological Park during the sketching period for Menagerie Manor.

Other illustrators who worked with Durrell were Barry L. Driscoll who illustrated Two in the Bush, Pat Marriott who illustrated Look at Zoos and Anne Mieke van Ogtrop who illustrated The Talking Parcel and Donkey Rustlers.

Durrell wrote a number of lavishly illustrated children's books in his later years. Graham Percy was the illustrator for The Fantastic Flying Journey and The Fantastic Dinosaur Adventure. Toby the Tortoise and Keeper were illustrated by Keith West. His Puppy board books were illustrated by Cliff Wright.

Honours and legacy

- Durrell was awarded the Order of the Golden Ark by Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands in 1981.

- In 1981, Durrell became a founding member of the World Cultural Council.[13]

- Durrell received the OBE in 1982.

- The National Youth Music Theatre performed the musical theatre The Carnival of the Animals at Fort Regent, Jersey as a tribute to Gerald Durrell in 1984.

- Durrell featured in the United Nations' Roll of Honour for Environmental Achievement in 1988, becoming part of 500 people ("Global 500") to be given this honour in the period 1987–92.

- The University of Kent started the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology (DICE) in 1989, the first graduate school in the United Kingdom to offer degrees and diplomas in conservation and biodiversity.

- The journal Biodiversity and Conservation brought out a special volume of the journal in tribute to Gerald Durrell, on the theme of "The Role of Zoos" in 1995, following his death.

- The Gerald Durrell Memorial Funds, launched in 1996, are granted in the field of conservation by the Wildlife Trust every year.

- The statue park in Miskolc Zoo, created a bust of Gerald Durrell in 1998. Whipsnade Zoo also unveiled a new island for housing primates dedicated to Durrell in 1998.[14]

- The Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition, owned by the Natural History Museum and BBC Wildlife, gives the Gerald Durrell Award for the best photograph of an endangered species, starting from 2001.

- The Durrell School in Corfu, established in 2002, offers an academic course and tours in the footsteps of the Durrells in Corfu. Botanist David Bellamy has conducted field trips in Corfu for the school.

- The town hall of Corfu announced in 2006 that it would rename Corfu Bosketto (a park in the city of Corfu) Bosketto Durrell, after Gerald and Lawrence Durrell as a mark of respect.[15]

- Wildlife Preservation Canada established the Gerald Durrell Society in 2006 as recognition for individuals who have made legacy gifts.

- The Gerald Durrell Endemic Wildlife Sanctuary in the Black River Valley in Mauritius, is the home of the Mauritius Wildlife Appeal Fund's immensely successful captive breeding programme for the Mauritius kestrel, pink pigeon and echo parakeet.

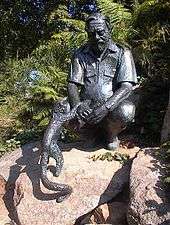

- The Durrell Wildlife Park has a bronze statue of Gerald Durrell by John Doubleday, cast along with a ruffed lemur at his knee and a Round Island gecko at his feet.

- Jersey brought out stamps honouring the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust and Mauritius brought out a stamp based on a race of a rare gecko named after Durrell.

- The de-rodentification of Rat Island in St. Lucia by the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust to create a sanctuary for the Saint Lucia whiptail lizard on the lines of Praslin Island has caused an official change in name for Rat Island. It is in the process of being renamed Durrell Island.

- The Visitors' Centre at the Belize Zoo is named the Gerald Durrell Visitors' Centre in honour of Durrell.

- Numerous individual animals of rare species born in captivity have been named "Gerry" or "Gerald" as homage to Durrell, among them the first Aldabra giant tortoise born in captivity.

- Cornwall college Newquay's centre for applied zoology has two buildings, one the Durrell Building, opened by his wife Lee Durrell in 2007

Species and homages

- Salanoia durrelli: a carnivoran species related to the brown-tailed mongoose, from Lake Alaotra, Madagascar. (2010)[16]

- Centrolene durrellorum: A glassfrog of the family Centrolenidae from the eastern Andean foothills of Ecuador, discovered in 2002 and described in 2005. This frog was named in honour of Gerald Durrell and his wife Lee Durrell "for their contributions to the conservation of global biodiversity".[17]

- Clarkeia durrelli: A fossil brachiopod of the order Atrypida, from the Upper Silurian age, discovered 1982 - there is presently no reference to indicate that this species was named in honour of Gerald Durrell

- Nactus serpensinsula durrellorum: The Round Island race of the Serpent Island gecko is a distinct subspecies and was named after both Gerald and Lee Durrell[18] for their contribution to saving the gecko and Round Island fauna in general. Mauritius released a stamp depicting the race.

- Ceylonthelphusa durrelli: Durrell's freshwater crab: A critically rare new species of Sri Lankan freshwater crab.

- Benthophilus durrelli: Durrell's tadpole goby: A new species of tadpole goby discovered in 2004

- Kotchevnik durrelli Yakovlev: A new species of moth of the superfamily Cossoidea from Russia

- Mahea durrelli Kment 2005: A new species of shield bug of the family Acanthosomatidae from Madagascar[19]

Major expeditions

| Year | Place | Primary purpose | Book | Film | Species in focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1947 / 1948 | Mamfe, British Cameroons (now Cameroon) | Independent animal collecting mission for British zoos | The Overloaded Ark | — | Angwantibo, giant otter shrew |

| 1949 | Mamfe and Bafut, British Cameroons (now Cameroon) | Independent animal collecting mission for British zoos | The Bafut Beagles | — | Galago, hairy frog, African golden cat, flying mouse |

| 1950 | British Guiana (now Guyana) | Independent animal collecting mission for British zoos | Three Singles to Adventure | — | Giant otter, poison arrow frogs, Surinam toad, capybara, Brazilian porcupine, curassow |

| 1953 / 1954 | Argentina and Paraguay | Partially sponsored animal collecting mission | The Drunken Forest | — | Burrowing owl, ovenbird, anaconda, rhea, giant anteater |

| 1957 | Bafut, British Cameroons (now Cameroon) | Animal collecting mission for his own to-be zoo | A Zoo in My Luggage | To Bafut With Beagles | Patas, galago, grey-necked rockfowl |

| 1958 | Patagonia, Argentina | Animal collecting mission for his own Jersey Zoo | The Whispering Land | Look (Argentinian Expedition) | South American fur seal, Patagonian hare, vampire bat, Magellanic penguin |

| 1962 | Malaysia, and Australia and New Zealand | Shooting of the BBC Nature series Two in the Bush | Two in the Bush | Two in the Bush | Kakapo, kākā, kea, tuatara, Sumatran rhinoceros, Leadbeater's possum |

| 1965 | Sierra Leone | Animal collecting mission for Jersey Zoo to be made into a TV series by BBC | Section of Catch Me a Colobus | Catch Me a Colobus | Colobus, African leopard, red river hog, potto |

| 1968 | Mexico | Animal collecting mission for Jersey Zoo | Section of Catch Me a Colobus | — | Volcano rabbit, thick-billed parrot |

| 1969 | Great Barrier Reef, Northern Territory and Queensland, Australia | Conservation fact-finding mission, with possible material for book never written | — | — | Great Barrier Reef species |

| 1976, 1977 | Mauritius and other Mascarene Islands | Two back-to-back in-situ conservation missions and animal collecting expeditions for local breeding and the Jersey Zoo | Golden Bats and Pink Pigeons | The Mauritius Conservation Mission, The Round Island Project | Pink pigeon, Rodrigues fruit bat, Round Island boa, Telfair's skink, Gunther's gecko, Mauritius kestrel |

| 1978 | Assam, India and Bhutan | In-situ conservation mission and filming for an episode in a BBC series | — | "Animals Are My Life" episode in The World About Us series | Pigmy hog |

| 1982 | Mauritius and other Mascarene Islands and Madagascar | In-situ conservation mission and animal collecting expedition for local breeding and Jersey Zoo to be filmed for a BBC TV series about the Trust's role in other countries | Ark on the Move | Ark on the Move | Pink pigeon, Rodrigues fruit bat, Round Island boa, Telfair's skink, Gunther's gecko, Mauritius kestrel, indri, Madagascan boa |

| 1984 | Russia | Shooting of the Channel 4 TV series Durrell in Russia | Durrell in Russia | Durrell in Russia | Przewalski's horse, saiga, cranes, Russian desman |

| 1989 | Belize | As part of Programme for Belize — a conservation project which aimed to conserve 250,000 acres (1000 km2) of tropical rain forest | — | — | Belizean rain forest species |

| 1990 | Madagascar | In-situ conservation mission and animal collecting expedition for local breeding and Jersey Zoo | The Aye-Aye and I | To the Island of Aye-Aye | Aye aye, indri, ring-tailed lemur, Alaotran lemur, tenrec |

Bibliography

Autobiographical

- The Overloaded Ark (Faber and Faber, 1953)

- Three Singles to Adventure (Three Tickets to Adventure) (Rupert Hart-Davis, 1954)

- The Bafut Beagles (Rupert Hart-Davis, 1954)

- The New Noah (Rupert Hart-Davis, 1955)

- The Drunken Forest (Rupert Hart-Davis, 1956)

- My Family and Other Animals (Rupert Hart-Davis, 1956)

- Encounters with Animals (Rupert Hart-Davis, 1958)

- A Zoo in My Luggage (Rupert Hart-Davis, 1960)

- The Whispering Land (Rupert Hart-Davis, 1961)

- Menagerie Manor (Rupert Hart-Davis, 1964)

- Two in the Bush (Collins, 1966)

- Birds, Beasts, and Relatives (Collins, 1969)

- Fillets of Plaice (Collins, 1971)

- Catch Me a Colobus (Collins, 1972)

- Beasts in My Belfry (A Bevy of Beasts) (Collins, 1973)

- The Stationary Ark (Collins, 1976) (mainly non-fictional content)

- Golden Bats And Pink Pigeons: A Journey to the Flora and Fauna of a Unique Island (Collins, 1977)

- The Garden of the Gods (Fauna and Family) (Collins, 1978)

- The Picnic And Suchlike Pandemonium (The Picnic and Other Inimitable Stories) (Collins, 1979) (with some fictional short stories)

- Ark on the Move (Coward McCann, 1982)

- How to Shoot an Amateur Naturalist (Collins, 1984)

- Durrell in Russia (with Lee Durrell) (MacDonald (Publisher) (UK) / Simon & Schuster (U.S.), 1986)

- The Ark's Anniversary (Collins, 1990)

- Marrying Off Mother and Other Stories (Harper-Collins, 1991) (with some fictional short stories)

- The Aye-Aye And I: A Rescue Journey to Save One of the World's Most Intriguing Creatures from Extinction (Harper-Collins, 1992)

- The Best of Gerald Durrell (edited by Lee Durrell) (Harper-Collins, 1996)

Non-fiction

- Island Zoo: The Animals a Famous Collector Couldn't Part with (photographs by W. Suschitzky) (Collins, 1961)

- Look At Zoos (Hamish Hamilton, 1961)

- A Practical Guide for the Amateur Naturalist (with Lee Durrell) (Hamish Hamilton (UK) / Alfred A. Knopf (U.S.), 1982)

Fiction

- The Donkey Rustlers (Collins, 1968)

- Rosy Is My Relative (Collins, 1968)

- The Talking Parcel (Battle for Castle Cockatrice) (Collins, 1974)

- The Mockery Bird (The Billion Dollar Brain) (Collins, 1981)

- The Fantastic Flying Journey: An Adventure in Natural History (Conran Octopus, 1987)

- The Fantastic Dinosaur Adventure: A New Adventure in Natural History (Conran Octopus, 1989)

- Keeper (Michael O'Mara Books, 1990)

- Toby the Tortoise (Michael O'Mara Books, 1991)

- Puppy Tales: Puppy's Beach Adventure, Puppy's Field Day, Puppy's Pet Pals, Puppy's Wild Time (Andrex, 1993)

Unpublished

- Animal Pie, an unpublished book of lighthearted animal poems and caricatures, written in the 1950s [referenced in the official Douglas Botting biography]

Contributions

- Durrell, Lee (1986). State of the Ark: An atlas of conservation in action. Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0-370-30754-1. (Foreword; the book is also dedicated to him.)

- Wilkinson, Peter; Helen Gilks (1993). Wildlife Photographer of the Year. Portfolio 2. Fountain. ISBN 978-0-86343-306-1. (Foreword)

Books edited by Durrell

- My Favourite Animal Stories (Arrow Books, 1962)

In case of simultaneous releases in many countries, the UK edition is referred to, except for companion books to TV series where both the UK and US editions are referred to.

Reference books

Biographies and other references

- Himself and Other Animals – A Portrait of Gerald Durrell, David Hughes (1976)

- In The Footsteps of Lawrence Durrell and Gerald Durrell in Corfu (1935–39), Hilary Whitton Paipeti (1998)

- Gerald Durrell – The Authorized Biography, Douglas Botting (1999)

- "Durrelliania": An Illustrated Checklist of Inscribed Books of Lawrence Durrell and Gerald Durrell and Associated Publications, Letters and Notes in the Library of Jeremy J. C. Mallinson, edited by Jeremy Mallinson (1999)

- Amateurs in Eden – The Story of a Bohemian Marriage: Nancy and Lawrence Durrell, Joanna Hodgkin (2012)

Jersey Zoo and Durrell Wildlife Preservation Trust books

- A Brush with Animals, Ralph Thompson (illustrations by author) (1963)

- Okavango Adventure: In Search of Animals in Southern Africa, Jeremy Mallinson (1973)

- Earning Your Living with Animals, Jeremy Mallinson (1975)

- The Facts About a Zoo: Featuring the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust, Jeremy Mallinson (1980)

- State of the Ark: An Atlas of Conservation in Action, Lee Durrell (1986)

- Travels in Search of Endangered Species, Jeremy Mallinson (1989)

- Gerald Durrell's Army, Edward Whitley (1992)

- Jambo: A Gorilla's Story, Richard Johnstone-Scott (1995)

Companion books to TV series not co-authored by Durrell

- Ourselves and Other Animals: From the TV Series with Gerald and Lee Durrell, Peter Evans (1987)

Books by family and friends

- Prospero's Cell: A Guide to the Landscape and Manners of the Island of Corcyra, Lawrence Durrell (1945)

- Beasts in My Bed, Jacquie Durrell (1967)

- Spirit of Place: Essays and Letters on Travel, Lawrence Durrell (1969)

- Island Trails, Theodore Stephanides (1973)

- Intimate Relations, Jacquie Durrell (1976)

- Whatever Happened to Margo, Margaret Durrell (1995) (written in the 1960s)[20]

- Autumn Gleanings: Corfu Memoirs and Poems, Theodore Stephanides (2011) (written in the 1970s or so)

Selected articles

- I am sort of caged in my own zoo[21]

Radio and filmography

Featuring the subject

- Encounters With Animals, Radio series, BBC (1957)

- To Bafut With Beagles, TV series, BBC (1958)

- Look (Argentinian Expedition), Single episode in TV series, BBC (1961)

- Zoo Packet, TV series, BBC (1961)

- Animal Magic, Early episodes in TV series, BBC (1962–1983)

- Two in the Bush, TV series, BBC (1963)

- Catch Me a Colobus, TV series, BBC (1966)

- The Garden of the Gods, TV series, BBC (1967)

- The Stationary Ark, TV series, Primedia (Canada) / Channel 4 (UK) (1975)

- Animals Are My Life, episode in the TV series The World About Us, BBC (1978)

- Ark on the Move, TV series, Primedia (Canada) / Channel 4 (UK) (1982)

- The Amateur Naturalist, TV series, CBC / Channel 4 (UK) (1983)

- Ourselves & Other Animals, TV series, Primetime Television and Harcourt Films (1987). Directed by Jeremy marre

- Durrell in Russia, TV series, Channel 4 (UK) (1986)

- Durrell's Ark, one hour documentary, BBC (1988)

- A Day at the Zoo with Phillip Schofield, one hour episode featuring Durrell and Jersey Zoo (1989)

- Gerald Durrell – Himself and Other Animals, documentary, Green Umbrella Productions (1999)

- Gerald Durrell – Jambo the Gentle Giant, documentary, Green Umbrella Productions (1999)

- Gerald Durrell – To the Island of the Aye-Aye, documentary, Green Umbrella Productions (1999)

- Safe Hands in a Wild World, documentary, Green Umbrella Productions (1999)

- Inside Jersey Zoo, re-release, UK PC Advisor magazine (2001)

- The Round Island Project, re-release, UK PC Advisor magazine (2001)

- The Mauritius Conservation Mission, re-release, UK PC Advisor magazine (2001)

- My Family And Other Animals, the film version of his autobiography as a child (2005)

- My Family and Other Animals (Radio Play), BBC Radio 4 (2010)

- The Durrells (6-part TV series) ITV (2016

On the subject

- A Memorial Celebration for the Life of Gerald Durrell (1995)

- World of Animals episode on Gerald Durrell and Jersey Zoo, Channel One, Moscow (2004)

- The Wild Life of Gerald Durrell, BBC Four (December 2005)

- Wildlife in a War Zone, using archival Durrell footage and examining the changes brought about by war in Sierra Leone, Animal Planet, May 2006

- Archive Hour with Bridget Nicholls: Discover Your Inner Durrell, BBC Radio 4 (September 2006)[22]

- Fierce Creatures, a 1997 comedic film about a zoo in peril of being closed written by John Cleese, starring Cleese, Jamie Lee Curtis, Kevin Kline, and Michael Palin, is dedicated to Gerald Durrell and British humorist Peter Cook in the closing credits, with their photographs and dates of birth and death.[23]

Movies

- The Talking Parcel, Animated movie, directed by Brian Cosgrove, Cosgrove Hall (1979)

- My Family and Other Animals, TV series, BBC (1989)

- My Family and Other Animals, Radio drama, BBC Radio 4 (2001)

- The Fantastic Flying Journey, Animated TV series, directed by Catherine Robbins and John Coates, Two Sides TV / TV Loonland (2001)

- My Family and Other Animals (remake), BBC 2005 film broadcast in America on PBS - Masterpiece Theatre in 2006.[24]

- The Durrells, a six-part TV series loosely based on Durrell's three autobiographical books about his family's time on Corfu, ITV (2016)

Screenplays

- Tarka the Otter, movie, directed by David Cobham (1979)

Limericks

Durrell quoted numerous bawdy limericks in his Corfu Trilogy which have not been documented elsewhere, and it is probable that some of these owe their origins to Lawrence Durrell, Edward Lear and Theodore Stephanides. Gerald Durrell is himself the subject of a few limericks written later.[25]

Time capsule

A time capsule buried at Jersey Zoo in 1988 contains the following popular quote by Durrell, often used in conservation awareness campaigns:

We hope that there will be fireflies and glow-worms at night to guide you and butterflies in hedges and forests to greet you.

We hope that your dawns will have an orchestra of bird song and that the sound of their wings and the opalescence of their colouring will dazzle you.

We hope that there will still be the extraordinary varieties of creatures sharing the land of the planet with you to enchant you and enrich your lives as they have done for us.

We hope that you will be grateful for having been born into such a magical world.

References

- ↑ "Chapter One of Gerald Durrell: The Authorized Biography By Douglas Botting". New York Times. 12 December 1999. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ↑ (Thomson 1998)

- ↑ (McNiven 1998, pp. 79).

- ↑ Jacquie Durrell, Beasts in My Bed, Fontana 1967

- ↑ "Curtis Brown". Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 2014-03-16.

- ↑ "BBC Radio 4 Extra - Gerald Durrell - My Family and Other Animals". BBC. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ↑ "BBC Radio 4 - Great Lives, Series 25, Gerald Durrell". BBC. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ↑ "Gerald Durrell's Jersey wildlife conservation trust celebrates 50th anniversary". Telegraph.co.uk. 10 April 2009. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Jones_(biologist)

- ↑ Botting. page 588

- ↑ Botting. page 598

- ↑ "About Us". World Cultural Council. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ↑ (Gruner 1998)

- ↑ Helena Smith. "Corfu pays belated tribute to Durrells". the Guardian. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ↑ "US News". US News. 13 October 2010. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- ↑ Cisneros-Heredia, D. F. (2007) A new species of glassfrog of the genus Centrolene from the foothills of Cordillera Oriental of Ecuador (Anura: Centrolenidae). Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. Herpetozoa, 20 (1/2), 27–34. (PDF available by clicking here Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Beolens B, Watkins M, Grayson M. 2011. The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Durrell", p. 78).

- ↑ Kment, P. 2005. Revision of Mahea Distant, 1909, with a review of the Acanthosomatidae (Insecta: Heteroptera) of Madagascar and Seychelles. ACTA ENTOMOLOGICA MUSEI NATIONALIS PRAGAE. Volume 45, pp. 21–50; Available at "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- ↑ Robin Balke, Paperback reviews, The Independent, 13 October 1996

- ↑

- ↑ 'Archive Hour with Bridget Nicholls: Discover Your Inner Durrell' Archived 29 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine., BBC Radio 4 (September 2006)

- ↑ 'Fierce Creatures' Archived 2 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. (1997).

- ↑ "Drama - My Family and Other Animals". BBC. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- ↑ "see here". Oedilf.com. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gerald Durrell. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Gerald Durrell |

- Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust

- TIME magazine report of Durrell's 1973 tour at the Wayback Machine (archived 30 September 2007)

- BBC database of Gerald Durrell

- Gerald Durrell database of films at the BFI

- Gerald Durrell at the Internet Movie Database

- Profile of George Cansdale