George Taylor House (Catasauqua, Pennsylvania)

|

George Taylor House | |

|

Home built by George Taylor, a signer of the Declaration of Independence | |

| |

| Location | Lehigh & Poplar Sts., Catasauqua, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°38′52″N 75°27′59″W / 40.64778°N 75.46639°WCoordinates: 40°38′52″N 75°27′59″W / 40.64778°N 75.46639°W |

| Built | 1768 |

| Architectural style | Georgian |

| NRHP Reference # | 71000709 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | July 17, 1971[1] |

| Designated NHL | July 17, 1971[2] |

The George Taylor House, also known as George Taylor Mansion, was the home of George Taylor, a signer of the Declaration of Independence.[2]

The home, which is located in Catasauqua, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, was built by Taylor in 1768. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1971.[2] The Borough of Catasauqua purchased the house from the Lehigh County Historical Society in 2009 and today sponsors events and offers tours of the property at the borough's southwestern corner near the historic Lehigh River Canal.[3][4]

The house's first owners

The George Taylor House's first three owners were men of substantial means, who played notable roles locally and nationally in events leading up to the nation's founding.

George Taylor, 1768–76

George Taylor was born in northern Ireland in 1716 and immigrated to the American colonies in 1736.[5] Starting as an Indentured laborer , he built a successful career as an ironmaster in Pennsylvania, first at Warwick Furnace and Coventry Forge in Chester County and later at Durham Furnace in Bucks County.[6]

In 1767, Taylor purchased a 331-acre (1.34 km2) estate in Biery's Port (now part of Catasauqua) for £700. On this expansive property overlooking the Lehigh River, he built what was then one of the finest homes in the region, the house now named for him.[7] Shortly after the Taylors moved in, his wife Ann died.[7] Taylor continued to live here for the next six years, but in 1774, he returned to Durham to operate the ironworks under a new lease.[6] Until that time, production at Durham Furnace had focused on domestic products, primarily plates for stoves and fireplaces but also cast iron pots and pans. With the start of the Revolutionary War in 1775, the mill became a major supplier of cannon shot to the Continental Army and Navy.[8]

Taylor first entered the public arena in the late 1750s as a justice of the peace, a judicial post that was important in colonial times, when travel to the county courthouse was difficult. He was subsequently elected to the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, representing Northampton County from 1764-69.[5] In 1775, he was re-elected to the Assembly and on July 20, 1776, was appointed to the Continental Congress. Two weeks later, on August 2, he signed the Declaration of Independence, along with most of the congressional delegates.[9]

Four months before joining the Congress, Taylor sold his Biery's Port property to John Benezet of Philadelphia.[10] The next year, in March 1777, Taylor was named to Pennsylvania's new Supreme Executive Council, a 12-member body that acted in the capacity of governor. In ill health, he resigned from the council after just a few months, ending his public career. Taylor remained active in iron making over the next three years, but retired to Easton in 1780. Less than a year later, on February 23, 1781, he died at the age of 65.[6]

John Benezet, 1776–82

John Benezet was a native of Philadelphia and the son of Daniel Benezet, a prominent Philadelphia merchant.[11] Benezet briefly attended the College of Philadelphia in 1757 and was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1768. In 1775, he married Hanna Bingham, and with that, his father gave him £3,000 plus £6,000 in stock to set up an import business. On March 27, 1776, Benezet purchased George Taylor's estate for £1,800.[7]

Benezet, like Taylor, became active in political affairs, but only briefly. In early 1775, he served as one of the secretaries who recorded proceedings at the Pennsylvania Provincial Congress, a meeting Taylor also attended.[12] In August of that year, he was named to Philadelphia's Committee of Correspondence.

Two years later, in 1777, the Continental Congress appointed Benezet as Commissioner of Claims in the Treasury Office. However, he resigned in 1778 and returned to his business interests.[13] Benezet died in the winter of 1780-81, when his ship, the Shillelagh, was lost at sea during a voyage to France.[11]

David Deshler, 1782–96

In 1782, Benezet's widow sold the Biery's Port estate to David Deshler for the same amount her husband had paid six years before.[7] Born in Switzerland in 1734, Deshler came to the American colonies as an infant. His father Adam Deshler was one of the earliest residents of the northern section of present-day Lehigh County. The owner of a significant amount of property, he personally built Fort Deshler in Whitehall Township in 1760 to protect local settlers against Indian attack.[14]

When David Deshler purchased Taylor's former house, he was living in Northampton Town (now Allentown) in what was then part of Northampton County. Deshler built Northampton Town's first house in 1762, the year of the town's founding. Initially, he operated a store and tavern here, but later started a saw mill and grist mill, Northampton Town's first industries. By the mid-1770s, he was one of the region's wealthiest men.[15]

In 1774, Deshler was appointed to the county's Committee of Observation, and in 1776, he was elected to the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, where he served with George Taylor. During the Revolutionary War, Deshler's properties in Northampton Town were used to produce munitions and manufacture, repair and store materials for the Continental Army.[14] In 1777, the Assembly appointed him one of four "sub-lieutenants" in charge of the county's military preparations. Deshler, who held the rank of colonel in the militia, was named a Commissioner of Purchases in February 1778, Assistant Forage Master in April 1780 and Assistant Commissary of Purchases in July 1780.[15]

The war ended in 1783, and the next year Deshler was re-elected to the Provincial Assembly as a representative of Northampton County. In 1787, he served as a delegate to the state convention that ratified the federal Constitution. After completing his final term in the Assembly in 1788, he retired from public service. Deshler lived out his days at Biery's Port, where he died at the age of 62 on December 24, 1796.[14]

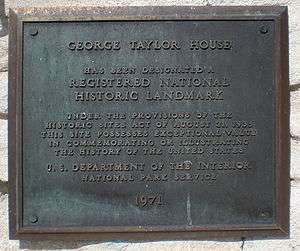

National Historic Landmark

During the 1800s, George Taylor's former house passed through various hands and was eventually acquired by Wahneta Silk Company, which built a mill in front of the house around 1890.[16] Meanwhile, the property was left to deteriorate for many years. In 1945, the Lehigh County Historical Society rescued the house, raising funds from its members for the acquisition and repairs.[7] Since then, the historical society has completed extensive restoration work.[17]

On July 17, 1971, the George Taylor House was registered as a National Historic Landmark.[2] After a fire destroyed the former silk mill (then a furniture factory) in 1982, the society purchased the property and extended the front lawn to provide a park-like setting for the historic site.[17]

In 2008, the society proposed selling the house to the Borough of Catasauqua for $250,000, stating "We believe that they can do much more with the site than we can. We believe the highest and best use of the property is with the good people of Catasauqua because it can be used for so many community type events."[18]

On May 5, 2013, as part of the Lehigh County Bicentennial celebration, a monument, designed by Jirair Youssefian of Vitetta Architects & Engineers, was unveiled during a ceremony held on the front lawn of the house. The monument will serve as the base for a future statue of George Taylor, which is currently in the planning stages.[19]

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 4 "George Taylor House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ "George Taylor House - Got George?". Borough of Catasauqua.

- ↑ Clark, Adam (February 5, 2012). "Catasauqua's revolutionary connection". The Morning Call.

- 1 2 "Biographical Directory of the United States Congress". Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- 1 2 3 Ely, Warren S. (1926). "George Taylor, Signer of the Declaration of Independence". A Collection of Papers Read Before the Bucks County Historical Society. Meadville, Pennsylvania: Bucks County Historical Society. V: 100–112. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wilcox, William J. (1946). "The George Taylor House at Catasauqua: A Brief History and Statement Concerning a Noteworthy Acquisition". 1946 Proceedings. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Lehigh County Historical Society: 47–51.

- ↑ The Committee on Historical Research, Pennsylvania Society of the Colonial Dames of America (1914). Forges and Furnaces in the Province of Pennsylvania. Lancaster, Pennsylvania: New Era Printing Company. pp. 43–57.

- ↑ "Signers of the Declaration: Biographical Sketches". Washington, DC: National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ↑ Fackenthal, Benjamin Franklin (1926). "The Homes of George Taylor". A Collection of Papers Read Before the Bucks County Historical Society. Meadville, Pennsylvania: Bucks County Historical Society. V: 112–133. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- 1 2 Bell, Jr., Whitfield J. (1999). Patriot-Improvers: Biographical Sketches of Members of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 2, 1768. Philadelphia: American Philosophical society. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ↑ "Pennsylvania Archives: Proceedings of the Convention for the Province of Pennsylvania". Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: William and Thomas Bradford. 1775. Retrieved 2014-09-14.

- ↑ Hayden, Rev. Horace Edwin (1903). "The Reminiscences of David Hayfield Conyngham, 1750–1834 of the Revolutionary House of Conyngham and Nesbitt". Proceedings and Collections of the Wyoming Historical and Geological Society for the years 1902–1903. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: E.B. Yordy Co. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- 1 2 3 Roberts, Charles R. (1908). "Revolutionary Patriots of Allentown and Vicinity". 1908 Proceedings. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Lehigh County Historical Society: 200–201.

- 1 2 Kohl, Helen Wittman; Kohl, John Young (1946). "Colonel David Deshler Allentown's First Citizen". 1946 Proceedings. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Lehigh County Historical Society: 9–46.

- ↑ Fox, Martha Capwell (2002). Catasauqua and North Catasauqua. Mount Pleasant, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 18. Retrieved 2008-08-31.

- 1 2 "George Taylor Mansion". Historic Catasauqua Preservation Association website. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved 2008-08-31.

- ↑ Jackson, Kurt Beldon (March 26, 2008). "Is timing right for Catasauqua to buy historic landmark? ** Borough may give George Taylor House its "best use,' but recession may hurt chances.". The Morning Call. pp. B.4.

- ↑ Cmil, Paul (May 16, 2013). "Monument is unveiled at historic house". www.thelehighvalleypress.com. Retrieved Feb 18, 2016.

External links

- The Borough of Catasauqua: George Taylor House

- Delaware & Lehigh National Heritage Corridor: George Taylor House

- Historic Catasauqua Preservation Association