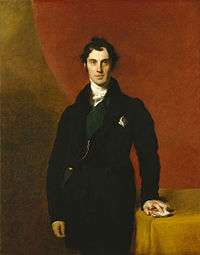

George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen

| The Right Honourable The Earl of Aberdeen KG KT FRSE FRS PC FSA Scot | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |

|

In office 19 December 1852 – 30 January 1855 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Derby |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Palmerston |

| Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs | |

|

In office 2 September 1841 – 6 July 1846 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Prime Minister | Sir Robert Peel |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Palmerston |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Palmerston |

|

In office 2 June 1828 – 22 November 1830 | |

| Monarch | George IV |

| Prime Minister | The Duke of Wellington |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Dudley |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Palmerston |

| Secretary of State for War and the Colonies | |

|

In office 20 December 1834 – 8 April 1835 | |

| Monarch | William IV |

| Prime Minister | Sir Robert Peel |

| Preceded by | Thomas Spring Rice |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Glenelg |

| Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster | |

|

In office 26 January 1828 – 2 June 1828 | |

| Monarch | George IV |

| Prime Minister | The Duke of Wellington |

| Preceded by | The Lord Bexley |

| Succeeded by | Charles Arbuthnot |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

George Gordon 28 January 1784[1] Edinburgh, Midlothian, Scotland |

| Died |

14 December 1860 (aged 76)[1] St James's, Middlesex, England |

| Political party | Peelite |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 4 |

| Alma mater | St John's College, Cambridge |

| Religion | Church of England |

| Signature |

|

George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen, KG, KT, FRSE, FRS, PC, FSA Scot (28 January 1784 – 14 December 1860),[1] styled Lord Haddo from 1791 to 1801, was a British politician, diplomat and landowner, successively a Tory, Conservative and Peelite, who served as Prime Minister from 1852 until 1855 in a coalition between the Whigs and Peelites, with Radical and Irish support. The Aberdeen ministry was filled with powerful and talented politicians, whom Aberdeen was largely unable to control and direct. Despite trying to avoid this happening, it took Britain into the Crimean War, and fell when its conduct became unpopular, after which Aberdeen retired from politics.

Aberdeen's career was dominated by foreign policy, but his experience did not prevent the slide towards the Crimean War. His personal life was marked by the loss of both parents by the time he was eleven, and of his first wife after only seven years of a happy marriage. His daughters died young, and his relations with his sons were difficult.[2] Before his marriage he travelled extensively in Europe, including Greece, and he had a serious interest in the classical civilisations and their archaeology. On his return to Britain in 1805 he devoted much time and energy to improving conditions on his Scottish estates.

After the death of his wife in 1812 he became a diplomat, almost immediately being given the important embassy to Vienna while still in his twenties. His rise in politics was equally rapid and lucky, and "two accidents — Canning's death and Wellington's impulsive acceptance of the Canningite resignations" led to him becoming Foreign Secretary to the Duke of Wellington in 1828 despite "an almost ludicrous lack of official experience"; he had been a minister for less than six months. After holding the position for two years, followed by another cabinet role, by 1841 his experience led to his appointment as Foreign Secretary again under Robert Peel for a longer term.[3] This was despite his being a "notoriously bad speaker", which mattered far less in the House of Lords, and having a "dour, awkward, occasionally sarcastic exterior".[4] Nonetheless his Peelite colleague, later himself Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone, said of him that he was "the man in public life of all others whom I have loved. I say emphatically loved. I have loved others, but never like him".[5]

Early life

Born in Edinburgh on 28 January 1784, he was the eldest son of George Gordon, Lord Haddo, son of George Gordon, 3rd Earl of Aberdeen. His mother was Charlotte, youngest daughter of William Baird of Newbyth.[6] He lost his father in 1791 and his mother in 1795 and was brought up by Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville and William Pitt the Younger.[1] He was educated at Harrow, and St John's College, Cambridge, where he graduated with a Master of Arts in 1804.[7] Before this, however, he had become Earl of Aberdeen on his grandfather's death in 1801,[1] and had travelled all over Europe. On his return to England, he founded the Athenian Society. In 1805, he married Lady Catherine Elizabeth, daughter of John Hamilton, 1st Marquess of Abercorn.

Political and diplomatic career, 1805–1828

In December 1805 Lord Aberdeen took his seat as a Tory Scottish representative peer in the House of Lords. In 1808, he was created a Knight of the Thistle. Following the death of his wife from tuberculosis in 1812 he joined the Foreign Service. He was appointed Ambassador Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Austria,[1] and signed the Treaty of Töplitz between Britain and Austria in Vienna in October 1813. In the company of the Austrian Emperor, Francis II he was an observer at the decisive Coalition victory of the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813; he had met Napoleon in his earlier travels. He became one of the central diplomatic figures in European diplomacy at this time,[1] and he was one of the British representatives at the Congress of Châtillon in February 1814, and at the negotiations which led to the Treaty of Paris in May of that year.[1][8]

Aberdeen was greatly affected by the aftermath of war which he witnessed at first hand. He wrote home:

The near approach of war and its effects are horrible beyond what you can conceive. The whole road from Prague to [Teplitz] was covered with waggons full of wounded, dead, and dying. The shock and disgust and pity produced by such scenes are beyond what I could have supposed possible...the scenes of distress and misery have sunk deeper in my mind. I have been quite haunted by them.[9]

Returning home he was created a peer of the United Kingdom as Viscount Gordon, of Aberdeen in the County of Aberdeen (1814),[1] and made a member of the Privy Council. In July 1815 he married his former sister-in-law Harriet, daughter of John Douglas, and widow of James Hamilton, Viscount Hamilton; the marriage was much less happy than his first. During the ensuing thirteen years Aberdeen took a less prominent part in public affairs.

Political career, 1828–1852

Lord Aberdeen served as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster between January and June 1828 and subsequently as Foreign Secretary until 1830 under the Duke of Wellington.[1] He resigned with Wellington over the Reform Bill of 1832.

He was Secretary of State for War and the Colonies between 1834 and 1835, and again Foreign Secretary between 1841 and 1846 under Sir Robert Peel. It was during his second stint as Foreign Secretary, that he had the harbor settlement of 'Little Hong Kong', on the south side of Hong Kong Island named after him. It was probably the most productive period of his career, that he settled two disagreements with the US – the Northeast Boundary dispute by the Webster-Ashburton Treaty (1842), and the Oregon dispute by the Oregon Treaty of 1846.[1] He also worked successfully to improve relationships with France, where Guizot had become a personal friend. He enjoyed the trust of Queen Victoria, which was still important for a Foreign Secretary. He again followed his leader and resigned with Peel over the issue of the Corn Laws.

After Peel's death in 1850 he became the recognised leader of the Peelites. In July 1852, a general election of Parliament was held which resulted in the election of 325 Tory/Conservative party members to Parliament. This represented 42.7% seats in Parliament. The main opposition to the Tory/Conservative Party was the Whig Party, which elected 292 members of the party to the Parliament in July 1852. Although occupying fewer seats than the Tory/Conservatives, the Whigs had a chance to draw support from the minor parties and independents who were also elected in July 1852. Lord Aberdeen as the leader of the Peelites was one of 38 Peelites elected to members of Parliament independently of the Tory/Conservative Party.[10]

While the Peelites agreed with the Whigs on issues dealing with the international trade, there were other issues which the Peelites disagreed with the Whigs. Indeed, Lord Aberdeen's own dislike of the Ecclesiastical Titles Assumption Bill, the rejection of which he failed to secure in 1851, prevented him from joining the government of Whig government of Lord John Russell in 1851. Additionally, 113 of the members of Parliament elected in July 1852 were Free Traders.[11] These members agreed with the Peelites on the repeal of the "Corn Laws," but they felt that the tariffs on all consumer products should be removed.

Furthermore, 63 members of Parliament elected in 1852, were members of the "Irish Brigade," who voted with the Peelites and the Whigs for the repeal of the Corn Laws because they sought an end the Great Irish Famine by means of cheaper wheat and bread prices for the poor and middle classes in Ireland.[12] Currently, however, neither the Free Traders and the Irish Brigade had disagreements with the Whigs that prevented them from joining with the Whigs form a government. Accordingly, the Tory/Conservative Party leader the Earl of Derby was asked to form a "minority government". However, the Earl of Derby appointed Benjamin Disraeli as the Chancellor of the Exchequer for the minority government.

When in December 1852, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer submitted his budget to Parliament on behalf of the minority government, the Peelites, the Free Traders and the Irish Brigade were all alienated by the proposed budget. Accordingly, each of these groups suddenly forgot their differences with the Whig Party and voted with the Whigs against the proposed budget. The vote was 286 in favour of the budget and 305 votes against the budget.[13] Because the leadership of the minority government had made the vote on the budget vote a "vote of confidence" in the minority government, the defeat of the Disraeli budget was a "vote of no confidence" in the minority government and meant the downfall of the minority government. Accordingly, Lord Aberdeen was asked to form a new government.

Prime Minister, 1852–1855

Following the downfall of the Tory/Conservative minority government under Lord Derby in December 1852, Lord Aberdeen formed a new government from the coalition of Free Traders, Peelites and Whigs that had voted no confidence in the minority government. Lord Aberdeen was able to put together a coalition government of these groups that held 53.8% of the seats of Parliament. Thus Lord Aberdeen, a Peelite, became Prime Minister and headed a coalition ministry of Whigs and Peelites.

Although united on international trade issues and on questions of domestic reform, his cabinet which also contained Lord Palmerston and Lord John Russell, who were certain to differ on questions of foreign policy. Charles Greville says in his Memoirs, "In the present cabinet are five or six first-rate men of equal, or nearly equal, pretensions, none of them likely to acknowledge the superiority or defer to the opinions of any other, and every one of these five or six considering himself abler and more important than their premier"; and Sir James Graham wrote, "It is a powerful team, but it will require good driving"; this Aberdeen was unable to provide. During the administration, much trouble was caused by the rivalry between these two, and over the course of it Palmerston managed to out-manoeuvre Russell to emerge as the Whig heir-apparent.[14] The cabinet also included a single Radical Sir William Molesworth, but much later, when justifying to the Queen his own new appointments, Gladstone told her: "For instance, even in Ld Aberdeen's Govt, in 52, Sir William Molesworth had been selected, at that time, a very advanced Radical, but who was perfectly harmless, & took little, or no part ... He said these people generally became very moderate, when they were in office", which she admitted had been the case.[15]

One of the foreign policy issues on which Palmerston and Russell disagreed was the type of relationship that Britain should have with France and especially France's ruler, Louis Bonaparte. Louis Bonaparte was the nephew of the famous Napoleon Bonaparte, who had become dictator and then Emperor of France from 1804 until 1814. Louis Bonaparte had been elected to a three-year term as President of the Second Republic of France on 20 December 1848. The Constitution of the Second Republic limited the President to a single term in office. Thus, Louis Bonaparte would be unable to succeed himself and after 20 December 1851 would no longer be President. Thus, on 2 December 1851, shortly before the end of his single three-year term in office was to expire, Louis Bonaparte staged a coup against the Second Republic in France, disbanded the elected Constituent Assembly, arrested some of the Republican leaders and declared himself Emperor Napoleon III of France.[16]

This coup upset many democrats in England as well as in France. Some British government officials felt that Louis Bonaparte was seeking foreign adventure in the spirit of his uncle—Napoleon I.[17] Consequently, these officials felt that any close association with Louis Bonaparte would eventually lead Britain into another series of wars, like the wars with France and Napoleon dating from 1793 until 1815. British relations with France had scarcely improved since 1815. As prime minister, the Earl of Aberdeen was one of these officials, who feared France and Louis Bonaparte. However, other British government officials were beginning to worry more about the rising political dominance of the Russian Empire in eastern Europe and the corresponding decline of the Ottoman Empire. Lord Palmerston, who at the time of Louis Bonaparte's 2 December 1851 coup was serving as the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in the Whig government of Prime Minister Lord John Russell. Without informing the rest of the cabinet or Queen Victoria, Palmerston had sent a private note to the French ambassador endorsing Louis Bonaparte's coup and congratulating Louis Bonaparte, himself, on the coup. Queen Victoria and members of the Russell government demanded that Palmerston be dismissed as Foreign Minister. John Russell requested Palmerston's resignation and Palmerston reluctantly provided it.

However, in February 1852, Palmerston took revenge on Russell by voting with the Conservatives in a "no confidence" vote against the Russell government. This brought an end to the Russell Whig government and set the stage for a general election in July 1852 which eventually brought the Conservatives to power in a minority government under the Earl of Derby. Another problem facing the Earl of Aberdeen in the formation of his new government in December 1852, was Lord Russell himself. Lord Russell was the leader of the Whig Party, the largest group in the coalition government. Consequently, Lord Aberdeen, was required to appoint Lord Russell as the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, which he had done on 29 December 1852. However, Lord Russell sometimes liked to use this position to speak for the whole government, as if he were the prime minister. In 1832, John Russell had been nicknamed "Finality John" because of his statement that the 1832 Reform Act had just been approved by both the House of Commons and the House of Lords would be the "final" expansion of the vote in Britain. There would be no further extension of the ballot to the common people of Britain. However, as political pressure in favour of further reform had risen over the twenty years since 1832, John Russell had changed his mind. While the Whigs were still part of the Opposition under the minority government of the Earl of Derby, John Russell had said, in January 1852, that he intended to introduce a new reform bill into the House of Commons which would equalise the populations of the districts from which members of Parliament were elected.[18]

Probably as a result of their continuing feud,[19] Palmerston declared himself against this Reform Bill of 1852. As a result, support for the Reform Bill of 1852 dwindled[20] Russell was forced to change his mind again and not introduce the any Reform Bill in 1852.[21] In order to form the coalition government, the Earl of Aberdeen had been required to appoint both Palmerston and Russell to his cabinet. Because of the controversy surrounding Palmerston's removal as Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs because of his letter to the French ambassador endorsing Louis Bonaparte's 2 December 1851 coup, Palmerston could not now be appointed Foreign Minister again so soon after his removal from the same position. Thus on 28 December 1852, the Earl of Aberdeen appointed Palmerston as Home Secretary and appointed John Russell as Foreign Minister.

The "Eastern Question"

Given the differences of opinion within the Lord Aberdeen cabinet over the direction of foreign policy with regard to relations between Britain and the French under Napoleon III, it is not surprising that debate raged within the government as Louis Bonaparte, now assuming the title of Emperor Napoleon III of France. As Prime Minister of the Peelite/Whig coalition government, the Earl of Aberdeen eventually led Britain into war on the side of the French/Ottomans against the Russian Empire. This war would eventually be called Crimean War, but the entire foreign policy negotiations surrounding the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire, which would continue throughout the middle and end of nineteenth century the problem would be referred to as the "Eastern Question".[22] Aberdeen was ordinarily a sympathiser with Russian interests against French/Napoleonic interests. Thus, he was really not in favour of the entrance of into the Crimean War. However, he was following the pressure that was being exerted on him from some members of his cabinet, including Palmerston, who in this rare instance was actually being supported by John Russell, both of whom were in favour of a more aggressive policy against perceived Russian expansion. Aberdeen, unable to control Palmerston, acquiesced. However the Eastern Question and the resulting Crimean War proved to be the downfall of his government.

The Eastern Question began as early as the 2 December 1852 with the Napoleonic coup against the Second Republic of France. As he was forming his new imperial government, Napoleon III sent an ambassador to the Ottoman Empire with instructions to assert France's right to protect Christian sites in Jerusalem and the Holy Land. The Ottoman Empire agreed to this condition to avoid conflict or potential war with France. Aberdeen, as Foreign Secretary, had himself tacitly authorised the construction of the first Anglican church in Jerusalem in 1845, following his predecessor's commission in 1838 of the first European Consul in Jerusalem on Britain's behalf, which lead to series of successive appointments by other nations. Both resulted from Lord Shaftesbury's canvassing with substantial public support.[23][24][25] Nevertheless, Britain became increasingly worried about the situation in Turkey and Prime Minister Aberdeen sent Lord Stratford de Redcliffe, a diplomat with vast experience in Turkey, as a special envoy to the Ottoman Empire to guard British interests. Russia protested the Turkish agreement with the French as a violation of the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca of 1778—the treaty which ended the Russo-Turkish War (1768–74). Under this treaty, the Russians had been granted the exclusive right to protect the Christian sites in the Holy Land. Accordingly. on 7 May 1853, the Russians sent Prince Alexander Sergeyevich Menshikov, one their premier statesmen to negotiate a settlement of the issue.[26] Prince Menshikov called the attention of the Turks to the fact that during the Russo-Turkish War, the Russians had occupied the Turkish controlled provinces of Wallachia and Moldavia on the north bank of the Danube River, but he reminded them that pursuant to the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca, however, the Russians had returned these "Danubian provinces" to Ottoman control in exchange for the right to protect the Christian sites in the Holy Land. Accordingly, the Turks reversed themselves and agreed with the Russians.

The French sent one of their premier ships-of-the-line, the Charlemagne to the Black Sea as a show of force. In light of the French show of force, the Turks, again, reversed themselves and recognised the French right to protect the Christian sites. Lord Stratford de Redcliffe was advising the Ottomans during this time[27] and later, it was alleged, that he had been instrumental in persuading the Turks to reject the Russian arguments.

As war became inevitable, Aberdeen wrote to Russell:

The abstract justice of the cause, although indisputable, is but a poor consolation for the inevitable calamities of all war, or for a decison which I am not without fear may prove to have been impolitic and unwise. My conscience upbraids me the more, because seeing, as I did from the first, all that was to be apprehended, it is possible that by a little more energy and vigour, not on the Danube, but in Downing Street, it might have been prevented.[28]

Crimean War 1853–1856

In response this latest change of mind by the Ottomans/Turks, the Russians, on 2 July 1853 occupied the Turkish-satellite states of Wallachia and Moldavia, as they had during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768-1774.[29] Almost immediately, the Russian troops deployed along the northern banks of the Danube River, implying that they may cross the river. Aberdeen ordered the British Fleet to Constantinople and later into the Black Sea.[1] On 23 October 1853, the Ottoman Empire declared war on Russia. A Russian naval raid on Sinope, on 30 November 1853, resulted in the destruction of the Turkish fleet in the battle of Sinope. When Russia ignored an Anglo-French ultimatum to abandon the Danubian provinces, Britain and France declared war on Russia on 28 March 1854. In September 1854, British and French troops landed on the Crimean peninsula at Eupatoria north of Sevastopol. The Allied troops then moved across the Alma River on 20 September 1854 at the battle of Alma and set siege to the fort of Sevastopol.

A Russian attack on the allied supply base at Balaclava on 25 October 1854 was rebuffed. The Battle of Balaclava is noted for its famous (or rather infamous) Charge of the Light Brigade. On 5 November 1854, Russian forces tried to relieve the siege at Sevastopol and tried to defeat the Allied armies in the field in the Battle of Inkerman. However, this attempt failed and the Russians were rebuffed. Dissatisfaction as to the course of the war arose in England. As reports returned detailing the mismanagement of the conflict arose Parliament began to investigate. On 29 January 1855, John Arthur Roebuck introduced a motion for the appointment of a select committee to enquire into the conduct of the war.[30] This motion was carried by the large majority of 305 in favour and 148 against.

Treating this as a vote of no confidence in his government, Aberdeen resigned, and retired from active politics, speaking for the last time in the House of Lords in 1858. In visiting Windsor Castle to resign, he told the Queen: "Nothing could have been better, he said than the feeling of the members towards each other. Had it not been for the incessant attempts of Ld John Russell to keep up party differences, it must be acknowledged that the experiment of a coalition had succeeded admirably. We discussed future possibilities & agreed that nothing remained to be done, but to offer the Govt to Ld Derby,...".[31] The Queen continued to criticise Lord John Russell, for his behaviour for the rest of his life, on his death in 1878 her journal records that he was: "A man of much talent, who leaves a name behind him, kind, & good, with a great knowledge of the constitution, who behaved very well, on many trying occasions; but he was impulsive, very selfish (as shown on many occasions, especially during Ld Aberdeen's administration) vain, & often reckless & imprudent".[32]

Family

Lord Aberdeen married Lady Catherine Elizabeth Hamilton, daughter of Lord Abercorn, in 1805. They had one son and three daughters, all of whom predeceased their father. In July 1815 he married Harriet, daughter of John Douglas, and widow of James Hamilton, Viscount Hamilton, his first wife's sister-in-law. They had four sons and one daughter. His eldest son, George, succeeded as fifth Earl, and was the father of John, the seventh Earl, who was created Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair in 1916. Aberdeen's second son was General Sir Alexander Hamilton-Gordon; his third son was the Reverend Douglas Hamilton-Gordon; and his youngest son Arthur Gordon was created Baron Stanmore in 1893. The Countess of Aberdeen died in August 1833. Lord Aberdeen died at Argyll House, St. James's, London, on 14 December 1860, and was buried in the family vault at Stanmore.[33] In 1994 the novelist, columnist and politician Ferdinand Mount used George Gordon's life as the basis for a historical novel, Umbrella.

Apart from his political career Aberdeen was also a scholar of the classical civilisations, who published An Inquiry into the Principles of Beauty in Grecian Architecture (London, 1822) and was referred to by his cousin Lord Byron in his English Bards and Scotch Reviewers (1809) as "the travell'd thane, Athenian Aberdeen." He was appointed Chancellor of the University of Aberdeen in 1827 and was President of the Society of Antiquaries of London.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Religious interests

Aberdeen's biographer Muriel Chamberlain summarises "Religion never came easy to him". In his Scots landowning capacity "North of the border, he considered himself ex officio a Presbyterian";[45] in England "he privately considered himself an Anglican", as early as 1840 told Gladstone he preferred what Aberdeen called "the sister church [of England]" and when in London worshipped at St James's Piccadilly.[46] He was ultimately buried in the Anglican parish church at Stanmore, Middlesex.

He was a member of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland from 1818 to 1828 and exercised his existing rights to present ministers to parishes on his Scottish estates through a time when the right of churches to veto the appointment or 'call' of a minister became so contentious as to lead in 1843 to the schism known as "the Disruption" when a third of ministers broke away to form the Free Church of Scotland. In the House of Lords, in 1840 and 1843, he raised two Compromise Bills to allow presbyteries but not congregations the right of veto. The first failed to pass (and was voted against by the General Assembly) but the latter, raised post-schism, became law for Scotland and remained in force until patronage of Scots livings was abolished in 1874.[47]

He is said in the last few months of his life, post Crimean War, to have declined to contribute to building a church on his Scotland estates because of sense of guilt in having "shed much blood", citing biblically King David's being forbidden to build the Temple in Jerusalem.[48]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Aberdeen, George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of,". Encyclopedia Britannica. I: A-ak Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopedia Britannica Inc. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- ↑ MacIntyre, 644

- ↑ MacIntyre, 641

- ↑ MacIntyre, 642, 644, both quoted

- ↑ MacIntyre, 643, quoted

- ↑ Dod, Robert P. (1860). The Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage of Great Britain and Ireland. London: Whitaker and Co. p. 81.

- ↑ "Gordon, George Hamilton (Lord Haddo) (GRDN800GH)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Chambers Biographical Dictionary, ISBN 0-550-18022-2, page 4

- ↑ Gordon, Arthur (1893). The Earl of Aberdeen. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. p. 31.

- ↑ Karl Marx, "Result of the Elections" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 11 (International Publishers: New York, 1979) p. 352.

- ↑ Karl Marx, "Result of the Elections" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Freederick Engels: Volume 11, p. 352.

- ↑ Karl Marx, "Result of the Elections" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 11, p. 352.

- ↑ Karl Marx, "The Defeat of the Ministry" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: volume 11, p. 466.

- ↑ Martin, 110-112

- ↑ Queen Victoria's Journals, Wednesday 28 April 1880, Windsor Castle, from Princess Beatrice's copies, Volume72 (1 January 1880-18 August 1880), p.167, online from the Bodleian Library

- ↑ See the "Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon" by Karl Marx, contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 11 (International Publishers: New York, 1979) pp. 99 through 197.

- ↑ Frederick Engels, "England" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 11, p. 198.

- ↑ Karl Marx, "England" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 11, pp. 205-208.

- ↑ Karl Marx, "Political Parties and Prospects" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 11, p. 370.

- ↑ Karl Marx, "Capital Punishment--Mr. Cobden's Pamphlet" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 11, p. 499.

- ↑ Karl Marx, "The Italian Insurrection--British Politics" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 11, p. 511.

- ↑ Karl Marx, "British Politics--Disraeli--The Refugees--Mazzini in London--Turkey" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 12, p. 5.

- ↑ Lewis, Donald (2 January 2014). The Origins of Christian Zionism: Lord Shaftesbury And Evangelical Support For A Jewish Homeland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 380. ISBN 9781107631960.

- ↑ Sokolow, Nahum (2015-09-27). History of Zionism, 1600-1918. 1. Charleston SC USA: Forgotten Books. p. 418. ISBN 9781330331842.

- ↑ Hyamson, Albert M., The British Consulate in Jerusalem in Relation to the Jews of Palestine, 1838-1914, ISBN 978-0404562786, cited in Lewis, D.

- ↑ Karl Marx, "Affairs in Holland--Denmark--Conversion of the British Debt--India, Turkey and Russia" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 12, p. 105.

- ↑ Karl Marx "Mazzini--Switzerland and Austria--Turkish Question" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 12, p. 109.

- ↑ Walpole, Spencer (1889). The Life of Lord John Russell - Volume II. London: Longmans, Green and Co. p. 204.

- ↑ Karl Marx, "Turkey and Russia--the Connivance of the Aberdeen Ministry with Russia--The Budget--Tax on Newspaper Supplements--Parliamentary Corruption" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 12, p. 145.

- ↑ Karl Marx, "Fall of the Aberdeen Ministry" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 13 (International Publishers: New York, 1980) p. 631.

- ↑ Queen Victoria's Journals, Tuesday 30 January 1855, Windsor Castle, Princess Beatrice's copies, Volume:39 (1 January 1855-30 June 1855), pp. 47-48, Online from the Bodleian Library

- ↑ Queen Victoria's Journals, Wednesday 29 May 1878, Balmoral Castle, Princess Beatrice's copies, Vol 68 (1 January 1878-24 June 1878), pp. 268-69, Online from the Bodleian Library

- ↑ "The Churches of Great Stanmore". St John Church, Stanmore.

- 1 2 3 G.E. Cokayne and V. Gibbs, Complete Peerage, 2nd ed., vol. 1, 1910, p. 15.

- 1 2 G.E. Cokayne and V. Gibbs, Complete Peerage, 2nd ed., vol. 1, 1910, p. 16.

- ↑ G.E. Cokayne and V. Gibbs, Complete Peerage, 2nd ed., vol. 1, 1910, p. 16 ; of Wakefield, Yorkshire ; according to local traditions recited in at least two books on Lord Aberdeen, Oswald Hanson was a blacksmith and his daughter a cook at the Strafford Arms, Wakefield; the third Earl was visiting Hatfield Hall near the town and ate at the pub; being so impressed by the food prepared there for him, he asked to meet the cook and she would become his wife (see M.E. Chamberlain, Lord Aberdeen: a Political Biography, 1983, p. 17 and W.D. Home, The Prime Ministers: Stories and Anecdotes, 1987, p. 133).

- ↑ There does not appear to be a published record of Oswald Hanson's wife.

- ↑ J. Debrett, The Baronetage of England, 1815, vol. ii, p. 1232

- ↑ G.E. Cokayne and V. Gibbs, Complete Peerage, 2nd ed., vol. 1, 1910, pp. 15-6 ; of Newbyth, Haddington.

- ↑ Debrett gives no name for William Baird's wife.

- ↑ G.E. Cokayne and V. Gibbs, Complete Peerage, 2nd ed., vol. 1, 1910, p. 16 ; sister of General Sir David Baird, Baronet.

- ↑ J. Debrett, The Baronetage of England, 1815, vol. ii, p. 1232 ; neither Debrett nor the ODNB article for Sir David Baird give a name for Alicia Johnstone's father ; both do state that he was from Hiltown.

- ↑ B. Carnduff, "Baird, Sir David, first baronet (1757–1829)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004 ; of Hiltown, Berwick

- ↑ Nothing is given about the mother.

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 22. Oxford University Press. 2004. p. 902. ISBN 0-19-861372-5.Article by Muriel E. Chamberlain.

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 22. p. 903.

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 22. pp. 902–903.

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 22. p. 907.

Bibliography

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon, 4th Earl of". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 46.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon, 4th Earl of". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 46.- Churchill, Winston S. (1958). The Great Democracies. A History of the English-Speaking Peoples. 4.

- MacIntyre, Angus, review of Lord Aberdeen. A Political Biography by Muriel E. Chamberlain, The English Historical Review, Vol. 100, No. 396 (Jul., 1985), pp. 641–644, Oxford University Press, JSTOR

- Martin, B. K., "The Resignation of Lord Palmerston in 1853: Extracts from Unpublished Letters of Queen Victoria and Lord Aberdeen", Cambridge Historical Journal, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1923), pp. 107–112, Cambridge University Press, JSTOR

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen. |

- More about The Earl of Aberdeen on the Downing Street website.

"Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon, Earl of". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

"Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon, Earl of". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen

- "Archival material relating to George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of George Hamilton Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Portraits of Catherine Elizabeth Gordon (née Hamilton), Countess of Aberdeen at the National Portrait Gallery, London

.svg.png)