Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou

| Geoffrey Plantagenet | |

|---|---|

|

Duke of the Normans Count of Anjou, Maine and Mortain | |

Enamel effigy of Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou on his tomb at Le Mans. His decorated shield shows the early origins of the Royal Arms of England. | |

| Count of Anjou | |

| Reign | 1129 – 7 September 1151 |

| Predecessor | Fulk the Younger |

| Successor | Henry Curtmantle |

| Born | 24 August 1113 |

| Died |

7 September 1151 (aged 38) Château-du-Loir, France |

| Burial | Le Mans Cathedral, Le Mans |

| Spouse |

Matilda of England (m. 1128–51; his death) |

| Issue Detail |

Henry II, King of England Geoffrey, Count of Nantes William, Viscount of Dieppe |

| House | Plantagenet |

| Father | Fulk, King of Jerusalem |

| Mother | Ermengarde, Countess of Maine |

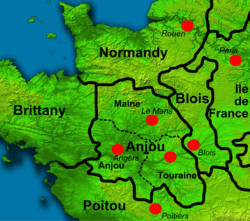

Geoffrey V (24 August 1113 – 7 September 1151) — called the Handsome or the Fair (French: le Bel) and Plantagenet — was the Count of Anjou, Touraine, and Maine by inheritance from 1129 and then Duke of Normandy by conquest from 1144. By his marriage to the Empress Matilda, daughter and heiress of Henry I of England, Geoffrey had a son, Henry Curtmantle, who succeeded to the English throne as King Henry II (1154-1189) and founded the Plantagenet dynasty the name of which was taken from Geoffrey's epithet. His ancestral domain of Anjou, also later gave rise to the names, Angevin, for three kings of England, and what became known as the Angevin Empire of the 12th century.

Biography

Early life

Geoffrey was the elder son of Foulques V d'Anjou and Eremburga de La Flèche, daughter of Elias I of Maine. He was named after his great-grandfather Geoffrey II, Count of Gâtinais. Geoffrey received his nickname from the yellow sprig of broom blossom (genêt is the French name for the planta genista, or broom shrub) he wore in his hat.[1]:9[2]:1 King Henry I of England, having heard good reports on Geoffrey's talents and prowess, sent his royal legates to Anjou to negotiate a marriage between Geoffrey and his own daughter, Empress Matilda. Consent was obtained from both parties, and on 10 June 1128 the fifteen-year-old Geoffrey was knighted in Rouen by King Henry in preparation for the wedding.

Marriage

Geoffrey and Matilda's marriage took place in 1128. The marriage was meant to seal a peace between England/Normandy and Anjou. She was eleven years older than Geoffrey, and very proud of her status as empress dowager (as opposed to being a mere countess). Their marriage was a stormy one with frequent long separations, but she bore him three sons and survived him.[1]:14–18

Count of Anjou

The year after the marriage Geoffrey's father left for Jerusalem (where he was to become king), leaving Geoffrey behind as count of Anjou. John of Marmoutier describes Geoffrey as handsome, red-headed, jovial, and a great warrior; however, Ralph of Diceto alleges that his charm camouflaged a cold and selfish character.

When King Henry I died in 1135, Matilda at once entered Normandy to claim her inheritance. The border districts submitted to her, but England chose her cousin Stephen of Blois for its king, and Normandy soon followed suit. The following year, Geoffrey gave Ambrieres, Gorron, and Chatilon-sur-Colmont to Juhel de Mayenne, on condition that he help obtain the inheritance of Geoffrey's wife.[3]

In 1139 Matilda landed in England with 140 knights, where she was besieged at Arundel Castle by King Stephen. In the "Anarchy" which ensued, Stephen was captured at Lincoln in February 1141, and imprisoned at Bristol. A legatine council of the English church held at Winchester in April 1141 declared Stephen deposed and proclaimed Matilda "Lady of the English". Stephen was subsequently released from prison and had himself recrowned on the anniversary of his first coronation.

During 1142 and 1143, Geoffrey secured all of Normandy west and south of the Seine, and, on 14 January 1144, he crossed the Seine and entered Rouen. He assumed the title of Duke of Normandy in the summer of 1144. In 1144, he founded an Augustine priory at Château-l'Hermitage in Anjou. Geoffrey held the duchy until 1149, when he and Matilda conjointly ceded it to their son, Henry, which cession was formally ratified by King Louis VII of France the following year.

Geoffrey also put down three baronial rebellions in Anjou, in 1129, 1135, and 1145–1151. He was often at odds with his younger brother, Elias, whom he had imprisoned until 1151. The threat of rebellion slowed his progress in Normandy, and is one reason he could not intervene in England. In 1153, the Treaty of Wallingford stipulated that Stephen should remain King of England for life and that Henry, the son of Geoffrey and Matilda should succeed him.[4]

Death

Geoffrey died suddenly on 7 September 1151. According to John of Marmoutier, Geoffrey was returning from a royal council when he was stricken with fever. He arrived at Château-du-Loir, collapsed on a couch, made bequests of gifts and charities, and died. He was buried at St. Julien's Cathedral in Le Mans France.[4]

Legacy

Children

Geoffrey and Matilda's children were:

- Henry II of England (1133–1189)

- Geoffrey, Count of Nantes (1 June 1134 Rouen- 26 July 1158 Nantes) died unmarried and was buried in Nantes

- William, Viscount of Dieppe (1136–1164) died unmarried

Geoffrey also had illegitimate children by an unknown mistress (or mistresses): Hamelin; Emme, who married Dafydd Ab Owain Gwynedd, Prince of North Wales; and Mary, who became a nun and Abbess of Shaftesbury and who may be the poet Marie de France. Adelaide of Angers is sometimes sourced as being the mother of Hamelin.[4]

Earliest heraldry?

It has long been thought that the earliest documented instance of heraldry was that in a report by Jean de Marmentier, a late-12th-century chronicler, that in 1128 Henry I of England knighted his son-in-law Geoffrey and granted him a badge of gold lions.[5] A gold lion may already have been Henry's own badge, and different lion motifs would later be used by many of his descendants. An enamel effigy (funerary plaque) created at the direction of his widow shows Geoffrey with a shield with gold lions on a blue background.[6] Thus, this may be evidence of one of the first authentic representations of a coat of arms[7] and, according to British historian Jim Bradbury, "suggests possible evidence for the early use of what became the English royal arms".[8] Bradbury also concedes, however, that "this is often discredited as written later" (i.e., two or three generations later by de Marmentier). According to French medievalist Michel Pastoureau, "for a long time heraldists believed that the earliest documented arms were those of Geoffrey Plantagenet…unfortunately [the] text was written after the death of Geoffrey…and the funerary plaque was created around 1155–60, at the request of his widow…. So Geoffrey Plantagenet probably never bore arms." Pastoureau adds that "Moreover, it has yet to be established which are the oldest extant arms, although that is a rather futile exercise".[9] Other scholars have found the evidence for Geoffrey's use of these arms compelling.[10]

Fictional portrayals

Geoffrey was portrayed by actor Bruce Purchase in the 1978 BBC TV series The Devil's Crown, which dramatised the reigns of his son and grandsons in England.

Geoffrey is an important character in Sharon Penman's novel When Christ and His Saints Slept, which deals with the war between his wife and King Stephen. The novel dramatises their stormy marriage and Geoffrey's invasion of Normandy on his wife's behalf.

Geoffrey features in Elizabeth Chadwick's novel Lady of the English which tells the story of Empress Matilda between 1125 and 1148. He also features in the first novel of Elizabeth Chadwick's trilogy about Eleanor of Aquitaine, The Summer Queen.

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- 1 2 Costain, Thomas B (1962). The Conquering Family. New York: Popular Library.

- ↑ Jones, Dan (2013). The Plantagenets: The Warrior Kings and Queens Who Made England. Viking. ISBN 9780670026654.

- ↑ Bradbury, Jim. 1990. "Geoffrey V of Anjou, Count and Knight", in The Ideals and Practice of Medieval Knighthood III, ed. Christopher Harper-Bill and Ruth Harvey. Rochester: Boydell Press.

- 1 2 3 Haskins, Charles H. 1912. "Normandy Under Geoffrey Plantagenet", The English Historical Review, volume 27 (July): 417–444.

- ↑ Woodcock, Thomas and John Martin Robinson (1988), The Oxford Guide to Heraldry, Oxford University Press, pg 10.

- ↑ Ailes, Adrian (1982). The Origins of The Royal Arms of England. Reading: Graduate Center for Medieval Studies, University of Reading. pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Gage, John (1999), Color and Culture: Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction, pg ??.

- ↑ Bradbury, Jim (2004), The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare, p. 273

- ↑ Pastoureau, Michel (1997), Heraldry: Its Origins and Meaning, London: Thames and Hudson/New Horizons; trans., Francisca Garvie, pg 18.

- ↑ Adrian Ailes (1982), The Origins of The Royal Arms of England, Reading: Graduate Center for Medieval Studies, University of Reading, pp. 52-53.

External links

| Geoffrey Plantagenet Born: 24 August 1113 Died: 7 September 1151 | ||

| Preceded by Ermengarde |

Count of Maine 1126–1151 |

Succeeded by Elias II |

| Preceded by Fulk V |

Count of Anjou 1129–1151 |

Succeeded by Henry II |

| Preceded by Eustace |

Count of Mortain 1141–1151 | |

| Preceded by Stephen |

Duke of Normandy 1144–1150 | |

.svg.png)

.svg.png)