Garonne

| Garonne | |

|---|---|

The Garonne at Bordeaux | |

Map of the Garonne | |

| Native name | La Garonne |

| Country | France, Spain |

| Basin | |

| Main source |

Pyrenees 2,600 m (8,500 ft) 42°36′26″N 0°57′56″E / 42.607295°N 0.965424°E |

| River mouth |

Gironde estuary, Atlantic Ocean 45°2′29″N 0°36′24″W / 45.04139°N 0.60667°WCoordinates: 45°2′29″N 0°36′24″W / 45.04139°N 0.60667°W |

| Basin size | Including Dordogne: 84,811 km2 (32,746 sq mi) |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Length | 602 km (374 mi) |

| Discharge |

|

The Garonne (French: Garonne, IPA: [ɡa.ʁɔn]; in Occitan, Catalan, Portuguese and Spanish: Garona; Latin: Garumna[1] or Garunna) is a river in southwest France and northern Spain, with a length of 602 kilometres (374 mi). It flows into the Atlantic Ocean at Bordeaux.

Geography

Sources

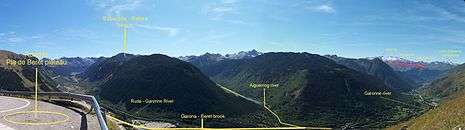

The Garonne's headwaters are to be found in the Aran Valley in the Spanish Pyrenees, though three different locations have been proposed as the true source: the Uelh deth Garona at Plan de Beret (42°42′34″N 0°56′43″E / 42.709494°N 0.945398°E), the Ratera-Saboredo cirque 42°36′26″N 0°57′56″E / 42.607295°N 0.965424°E), or the slopes of Pic Aneto (Salterillo-Barrancs ravine 42°38′59″N 0°40′06″E / 42.6498°N 0.6683°E according to the season).

The Uelh deth Garona at 1,862 metres (6,109 ft) above sea level has been traditionally considered as the source of the Garonne. From this point a brook (called the Beret-Garona) runs for 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) until the bed of the main upper Garonne valley. The river runs for another 38 kilometres (24 mi) until the French border at Pont de Rei, 40.5 kilometres (25.2 mi) in total.

The Ratera-Saboredo cirque is the head of the upper Garonne valley, and its upper lake at 2,600 metres (8,500 ft) above sea level is the origin of the Ruda-Garona river, running for 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) until the confluence with the Beret-Garona brook, and another 38 kilometres (24 mi) until the French border at Pont del Rei, 54 kilometres (34 mi) in total. At the confluence, the Ruda-Garona carries 2.6 cubic metres per second (92 cu ft/s) of water.[2][3] The Ratera-Saboredo cirque has been pointed by many researchers as the origin of the Garonne.[4][5][6][6][7]

The third thesis holds that the river rises on the slopes of Pic Aneto at 2,300 metres (7,500 ft) above sea level and flows by way of a sinkhole known as the Forau de Aigualluts (42°40′00″N 0°40′01″E / 42.6666°N 0.6669°E) through the limestone of the Tuca Blanca de Pomèro and a resurgence in the Val dera Artiga above the Aran Valley in the Spanish Pyrenees.[8] This underground route was suggested by the geologist Ramond de Carbonnières in 1787, but there was no confirmation until 1931, when caver Norbert Casteret poured fluorescein dye into the flow and noted its emergence a few hours later 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) away at Uelhs deth Joèu ("Jove's eyes" 42°40′51″N 0°42′28″E / 42.68092°N 0.7077°E) in the Artiga de Lin on the other side of the mountain.[9][10][11] From Aigualluts to the confluence with the main river at the bed of the upper Garonne valley at 800 metres (2,600 ft) above sea level, the Joèu has run for 12.4 kilometres (7.7 mi) (16 kilometres more to get to the French border), carrying 2.16 cubic metres per second (76 cu ft/s) of water, while the main river is carrying 17.7 cubic metres per second (630 cu ft/s).[2][3][12]

Despite the lack of universal agreement upon definition for determining a stream's source, the United States Geological Survey, the National Geographic Society, and the Smithsonian Institution agree that a stream's source should be considered as the most distant point (along watercourses from the river mouth) in the drainage basin from which water runs.[13][14][15][16][17]

The Ratera-Saboredo cirque is the "most distant point (along watercourses from the river mouth) in the drainage basin from which water runs",[18][19] and the source of the Garonne, according to the United States Geological Survey, the National Geographic Society, and the Smithsonian Institution convention upon determining a stream's source.

Course

The Garonne follows the Aran Valley northwards into France, flowing via Toulouse and Agen towards Bordeaux, where it meets the Gironde estuary. The Gironde flows into the Atlantic Ocean (Bay of Biscay). Along its course, the Garonne is joined by three other major rivers: the Ariège, the Tarn, and the Lot. Just after Bordeaux, the Garonne meets the Dordogne at the Bec d'Ambès, forming the Gironde estuary, which after approximately 100 kilometres (62 mi) empties into the Atlantic Ocean. Other tributaries include the Save and the Gers.

The Garonne is one of the few rivers in the world that exhibit a tidal bore.[20][21][22] Surfers and jet skiers could ride the tidal bore at least as far as the village of Cambes, 120 kilometres or 75 miles from the Atlantic, and even further upstream to Cadillac, although the tidal bore appears and disappears in response to changes in the channel bathymetry. In 2010 and 2012, some detailed field studies were conducted in the Garonne River (France) in the Arcins channel between Arcins Island and the right bank close to Lastrene township.[20] A striking feature of the field data sets was the large and rapid fluctuations in turbulent velocities and turbulent stresses during the tidal bore and flood flow.[21][22][23]

Towns along the river

- Aran Valley (Spain): Vielha, Bossòst

- Haute-Garonne (31): Saint-Gaudens, Muret, Toulouse

- Tarn-et-Garonne (82): Castelsarrasin

- Lot-et-Garonne (47): Agen, Marmande, Aiguillon

- Gironde (33): Langon, Bordeaux

Main tributaries

Following the flow of the river:

Navigation

The Garonne plays an important role in inland shipping. The river not only allows seagoing vessels to reach the port of Bordeaux but also forms part of the "Canal des Deux Mers", linking the Mediterranean Sea to the Atlantic Ocean, allowing a shorter and safer way for goods to pass from the agricultural areas of the South of France to the Atlantic.

From the ocean, ships pass through the Gironde estuary until the mouth of the Garonne (to the right of the Dordogne when sailing upstream). The Garonne remains navigable for larger vessels up to the "Pont de Pierre" (Stone Bridge) in Bordeaux. River vessels can sail upstream to Castets-en-Dorthe, where the Garonne Lateral Canal (Canal Latéral à la Garonne) joins the river.

Prior to the building of the Garonne Lateral Canal, constructed between 1838 and 1856, river shipping used the Garonne itself as far as Toulouse. However the navigation of the upper river was very uncertain, and this stretch of the river is no longer considered navigable. Instead the lateral canal takes the ships through 53 locks to the town of Toulouse, where the canal meets the Canal du Midi, the next stage of the "Canal des Deux Mers".[24]

The Garonne Lateral Canal was subject to one of the largest infrastructure works in Europe during the 19th century, when it was widened to accept the standardized barge dimension of 38 by 5 metres (125 by 16 ft). French minister Freycinet ordered that all major canals used for long distance transport be suitable for vessels of those standard dimensions. The extension of all of the former 30-metre (98 ft) locks to the new standard length was carried out throughout the lateral canal. The other half of the Canal des Deux Mers, the Canal du Midi, partly escaped this operation, because by the time the works had reached the area where the most locks were situated, commercial traffic on the canal had almost disappeared. The works were stopped, leading to the cultural heritage status of the United Nations that has made the Canal du Midi famous.[25]

See also

References

- ↑ Smith, William (1850). A new classical dictionary of Greek and Roman biography, mythology, and geography. London: John Murray. p. 492. OCLC 223027795.

- 1 2

- 1 2

- ↑ Datos sobre la vegetación y bioclima del Valle de Arán. Salvador Rivas-Martínez (member of the Spanish Royal Academy of Sciences, Manuel Costa (Professor of the Universitat de Valencia). Acta Bot. Barcinon. 45:473-499, 1998

- ↑ Soler i Santaló; La Vall d'Aran. Guía monográfica de la comarca; pág. 12. Barcelona, 1916.

- 1 2 Faura i Sans (M.); Sobre hidrología subterránea en los Pirineos Centrales de Aragón y Cataluña. Bol. de la Real Soc. de Hist. Nat, vom. XVI, pgs. 353-354. Madrid, 1916.

- ↑ Boletín del Centro Excursionista de Cataluña

- ↑ Reynolds, Kev (2001). Walks and Climbs in the Pyrenees. Milnthorpe, England: Cicerone Press. p. 208. ISBN 1-85284-328-4.

- ↑ Casteret, Norbert (1939). Ten Years Under the Earth. Mussey, Barrows (trans). London: J. M. Dent.

- ↑ Mapa topogràfic de Catalunya 1:100 000 (Map) (1st ed.). Institut Cartogràfic de Catalunya. § 1: Pirineu occidental.

- ↑ Lambert, Roger (1996). "A propos de la Garonne Supérieure". Géographie du cycle de l'eau (in French). Toulouse: Presses Universitaires du Mirail. p. 351. ISBN 978-2-85816-273-4.

prouvant péremptoirement que la Garonne a sa vrai source et la plus importante dans les Monts Maudits, sur le versant Sud des Pyrénées ('proving conclusively that the Garonne has its true source, and the most important, in the Monts Maudits, on the southern slopes of the Pyrenees')

- ↑

- ↑ "Largest Rivers in the United States" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ↑ National Geographic News @ nationalgeographic.com

- ↑ The True Utmost Reaches of the Missouri

- ↑ IBGE - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística

- ↑ Quest for the Missouri River Source, John LaRandeau, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

- ↑ Instituto Geográfico Nacional; Ministerio de FOmento. "Visor cartográfico del Instituto Geográfico Nacional". Instituto Geográfico Nacional de España. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ↑ s - Géoportail, le portail des territoires et des citoyens. "IGN France Cartes Topographie". Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- 1 2 Chanson, H., Lubin, P., Simon, B., and Reungoat, D. (2010). Turbulence and Sediment Processes in the Tidal Bore of the Garonne River: First Observations. Hydraulic Model Report No. CH79/10, School of Civil Engineering, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 97 pages. ISBN 978-1-74272-010-4.

- 1 2 Simon, B., Lubin, P., Reungoat, D., Chanson, H. (2011). Turbulence Measurements in the Garonne River Tidal Bore: First Observations. Proc. 34th IAHR World Congress, Brisbane, Australia, 26 June-1 July, Engineers Australia Publication, Eric Valentine, Colin Apelt, James Ball, Hubert Chanson, Ron Cox, Rob Ettema, George Kuczera, Martin Lambert, Bruce Melville and Jane Sargison Editors. pp. 1141–1148. ISBN 978-0-85825-868-6.

- 1 2 Chanson, H., Reungoat, D., Simon, B., Lubin, P. (2011). "High-Frequency Turbulence and Suspended Sediment Concentration Measurements in the Garonne River Tidal Bore". Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science. 95 (2–3): 298–306. Bibcode:2011ECSS...95..298C. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2011.09.012. ISSN 0272-7714.

- ↑ Reungoat, D., Chanson, H., Caplain, B. (2012). "Field Measurements in the Tidal Bore of the Garonne River at Arcins (June 2012)". Hydraulic Model Report No. CH89/12, School of Civil Engineering, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 121 pages. ISBN 9781742720616.

- ↑ McKnight, Hugh (2005). Cruising French Waterways (4th-US ed.). Sheridan House, Inc. p. 246. ISBN 1-57409-210-3. Retrieved 2010-11-23.

- ↑ NoorderSoft Waterways database

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Garonne. |

- French Waterways - River Garonne Information on the navigable lower Garonne

- History and real-time water heights of Garonne river and main tributaries