Scottish Gaelic

| Scottish Gaelic | |

|---|---|

| Gàidhlig | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈkaːlikʲ] |

| Native to |

United Kingdom Canada |

| Region | Scotland; Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia in Canada |

| Ethnicity | Scottish people |

Native speakers |

57,000 in Scotland (2011)[1] 87,000 people aged three and over in Scotland reported having some Gaelic language ability in 2011.[1] |

|

Indo-European

| |

Early forms |

Primitive Irish

|

| Scottish Gaelic orthography (Latin script) | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

gd |

| ISO 639-2 |

gla |

| ISO 639-3 |

gla |

| Glottolog |

scot1245[2] |

| Linguasphere |

50-AAA |

|

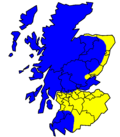

1891 distribution of English and Gaelic in Scotland | |

|

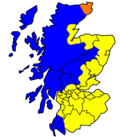

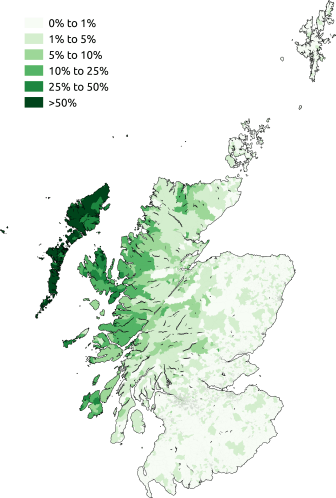

2001 distribution of Gaelic speakers in Scotland | |

Scottish Gaelic or Scots Gaelic, sometimes also referred to as Gaelic (Gàidhlig [ˈkaːlikʲ]), is a Celtic language native to Scotland. A member of the Goidelic branch of the Celtic languages, Scottish Gaelic, like Modern Irish and Manx, developed out of Middle Irish. It is thus ultimately descended from Old Irish.

The 2011 census of Scotland showed that a total of 57,375 people (1.1% of the Scottish population aged over three years old) in Scotland could speak Gaelic at that time, with the Outer Hebrides being the main stronghold of the language. The census results indicate a decline of 1,275 Gaelic speakers from 2001. A total of 87,056 people in 2011 reported having some facility with Gaelic compared to 93,282 people in 2001, a decline of 6,226.[1][3] Despite this decline, revival efforts exist and the number of speakers of the language under age 20 has increased.[4]

Scottish Gaelic is neither an official language of the European Union nor the United Kingdom. However, it is classed as an indigenous language under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, which the British government has ratified,[5] and the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005 established a language development body, Bòrd na Gàidhlig, "with a view to securing the status of the Gaelic language as an official language of Scotland".[6]

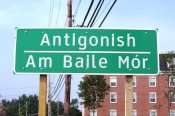

Outside Scotland, a group of dialects collectively known as Canadian Gaelic are spoken in parts of Atlantic Canada, mainly Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. In the 2011 census, there were 7,195 total speakers of "Gaelic languages" in Canada, with 1,365 in Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island where the responses mainly refer to Scottish Gaelic.[7] About 2,320 Canadians in 2011 also claimed Gaelic languages as their mother tongue, with over 300 in Nova Scotia (mostly in Cape Breton Island, Antigonish and Pictou) and Prince Edward Island.[8]

Nomenclature

.jpg)

Aside from "Scottish Gaelic", the language may also be referred to simply as "Gaelic". In Scotland, the word "Gaelic" in reference to Scottish Gaelic specifically is pronounced [ˈɡalɪk], while outside Scotland it is often pronounced /ˈɡeɪlᵻk/.[9] Outside Ireland and Great Britain, "Gaelic" may refer to the Irish language.[10]

Scottish Gaelic should not be confused with Scots, the Middle English-derived language varieties which had come to be spoken in most of the Lowlands of Scotland by the early modern era. Prior to the 15th century, these dialects were known as Inglis ("English") by its own speakers, with Gaelic being called Scottis ("Scottish"). From the late 15th century, however, it became increasingly common for such speakers to refer to Scottish Gaelic as Erse ("Irish") and the Lowland vernacular as Scottis.[11] Today, Scottish Gaelic is recognised as a separate language from Irish, so the word Erse in reference to Scottish Gaelic is no longer used.

History

Origins to zenith

It is commonly accepted by scholars today that Gaelic was brought to Scotland, probably in the 4th–5th centuries CE, by settlers from Ireland who founded the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata on Scotland's west coast in present-day Argyll.[12][13]

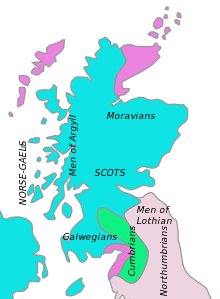

Gaelic in Scotland was mostly confined to Dál Riata until the 8th century, when it began expanding into Pictish areas north of the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde. This was spurred by the intermarriage of Gaelic and Pictish aristocratic families, the political merger of the two kingdoms in the early 9th century, and the common threat of attack by Norse invaders. By 900 Pictish appears to have become extinct, completely replaced by Gaelic.[14] An exception might be made for the Northern Isles, however, where Pictish was more likely supplanted by Norse rather than by Gaelic. During the reign of Caustantín mac Áeda (900–943), outsiders began to refer to the region as the kingdom of Alba rather than the kingdom of the Picts, but we do not know whether this was because a new kingdom was established or Alba was simply a closer approximation of the Pictish name for the Picts. However, though the Pictish language did not disappear suddenly, a process of Gaelicisation (which may have begun generations earlier) was clearly underway during the reigns of Caustantín and his successors. By a certain point, probably during the 11th century, all the inhabitants of Alba had become fully Gaelicised Scots, and Pictish identity was forgotten.[15]

By the 10th century, Gaelic had become the dominant language throughout northern and western Scotland, the Gaelo-Pictic Kingdom of Alba. Its spread to southern Scotland, was less even and totalizing. Place name analysis suggests dense usage of Gaelic in Galloway and adjoining areas to the north and west as well as in West Lothian and parts of western Midlothian. Less dense usage is suggested for north Ayrshire, Renfrewshire, the Clyde Valley and eastern Dumfriesshire. This latter region is roughly the area of the old Kingdom of Strathclyde, which was annexed by the Kingdom of Alba in the early 11th century, but may have continued to speak Cumbric as late as the 12th century. In south-eastern Scotland, there is no evidence that Gaelic was ever widely spoken. The area shifted from Cumbric to Old English during its long incorporation into the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria. After the Lothians were conquered by Malcolm II at the Battle of Carham in 1018, elites spoke Gaelic and continued to do so down to c. 1200. However, commoners retained Old English.[16]

With the incorporation of Strathclyde and the Lothians, Gaelic reached its social, cultural, political, and geographic zenith in Scotland. The language in Scotland had been developing features independently of the language in Ireland at least as early as its crossing the Druim Alban into Pictland.[17] The entire country was for the first time being referred to in Latin as Scotia and Gaelic was recognized as the lingua Scotia .[18][19]

Eclipse of Gaelic in Scotland

Many historians mark the reign of King Malcom Canmore (Malcolm III) as the beginning of Gaelic’s eclipse in Scotland.[20] In either 1068 or 1070, the king married the exiled Princess Margaret of Wessex. This future Saint Margaret of Scotland was a member of the royal House of Wessex which had occupied the English throne from its founding until the Norman Conquest. Margaret was thoroughly Anglo-Saxon and is often credited (or blamed) for taking the first significant steps in anglicizing the Scottish court. She spoke no Gaelic, gave her children Anglo-Saxon rather than Gaelic names, and brought many English bishops, priests, and monastics to Scotland. Her family also served as a conduit for the entry of English nobles into Scotland.[20] When both Malcolm and Margaret died just days apart in 1093, the Gaelic aristocracy rejected their anglicized sons and instead backed Malcolm’s brother Donald as the next King of Scots. Known as Donald Bàn (“the Fair”), the new king had lived 17 years in Ireland as a young man and his power base as an adult was in the thoroughly Gaelic west of Scotland. Upon Donald’s ascension to the throne, in the words of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, “the Scots drove out all the English who had been with King Malcolm”.[21] Malcolm’s sons fled to the English court, but in 1097 returned with an Anglo-Norman army backing them. Donald was overthrown, blinded, and imprisoned for the remaining two years of his life. Because of the strong English ties of Malcolm’s sons Edgar, Alexander, and David – each of whom became king in turn – Donald Bàn is sometimes called the ‘last Celtic King of Scotland’.[22] He was the last Scottish monarch to be buried on Iona, the one-time center of the Scottish Gaelic Church and the traditional burial place of the Gaelic Kings of Dàl Riada and the Kingdom of Alba.

During the reigns of the sons of Malcolm Canmore (1097–1153), Anglo-Norman names and practices spread throughout Scotland south of the Forth–Clyde line and along the northeastern coastal plain as far north as Moray. Norman French became dominant among the new feudal aristocracy, especially in southern Scotland, and completely displaced Gaelic at court. The establishment of royal burghs throughout the same area, particularly under David I, attracted large numbers of foreigners speaking ‘Inglis’, the language of the merchant class. This was the beginning of Gaelic’s status as a predominantly rural language in Scotland.[23] The country experienced significant population growth in the 12th and 13th centuries in the expanding burghs and their nearby agricultural districts.[24] These economic developments surely helped spread English as well.

Gaelic still retained some of its old prestige in medieval Scotland. At the coronation of King Alexander III in 1249, a traditional seanchaidh or story-teller recited the king’s full genealogy in Gaelic all the way back to Fergus Mòr, the mythical progenitor of the Scots in Dál Riata, “in accordance with the custom which had grown up in the kingdom from antiquity right up to that time”.[25] Clan chiefs in the northern and western parts of Scotland continued to support Gaelic bards who remained a central feature of court life there. The semi-independent Lordship of the Isles in the Hebrides and western coastal mainland remained thoroughly Gaelic since the language’s recovery there in the 12th century, providing a political foundation for cultural prestige down to the end of the 15th century.[26]

That being said, it seems clear that Gaelic had ceased to be the language of all of Scotland by 1400 at the latest. It disappeared from the central lowlands by c. 1350 and from the eastern coastal lowlands north of the Mounth not long afterwards. By the mid-14th century what eventually came to be called Scots (at that time termed Inglis) emerged as the official language of government and law.[27] Scotland’s emergent nationalism in the era following the conclusion of the Wars of Scottish Independence was organized using Scots as well. For example, the nation’s great patriotic literature including John Barbour’s The Brus (1375) and Blind Harry’s The Wallace (before 1488) was written in Scots, not Gaelic. It was around this time that the very name of Gaelic began to change. Down through the 14th century, Gaelic was referred to in English as 'Scottis', i.e. the language of the Scots. By the end of the 15th century, however, the Scottish dialect of Northern English had absorbed that designation. English/Scots speakers referred to Gaelic instead as 'Yrisch' or 'Erse', i.e. Irish.[23] King James IV (d. 1513) thought Gaelic important enough to learn and speak. However, he was the last Scottish monarch to do so.

Modern era

Scottish Gaelic has a rich oral and written tradition, referred to as beul-aithris in Scottish Gaelic, having been the language of the bardic culture of the Highland clans for many years. The language preserves knowledge of and adherence to pre-feudal 'tribal' laws and customs (as represented, for example, by the expressions tuatha and dùthchas). The language suffered particularly as Highlanders and their traditions were persecuted after the Battle of Culloden in 1746, and during the Highland Clearances.

An Irish translation of the Bible dating from the Elizabethan era was in use until the Bible was translated into Scottish Gaelic.[28] Author David Ross notes in his 2002 history of Scotland that a Scottish Gaelic version of the Bible was published in London in 1690 by the Rev. Robert Kirk, minister of Aberfoyle; however it was not widely circulated.[29] The first well-known translation of the Bible into Scottish Gaelic was made in 1767 when Dr James Stuart of Killin and Dugald Buchanan of Rannoch produced a translation of the New Testament. Very few European languages have made the transition to a modern literary language without an early modern translation of the Bible. The lack of a well-known translation until the late 18th century may have contributed to the decline of Scottish Gaelic.[28]

Pre-feudal attitudes antedating the Jacobite risings and Highland Clearances were still evident in the complaints and claims of the Highland Land League of the late 19th century. This political movement was successful in getting members elected to the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Land League was dissipated as a parliamentary force by the Crofters' Holdings Act 1886 and by the way the Liberal Party was seen to become supportive of Land League objectives.[30]

In the 21st century, Scottish Gaelic literature has seen development within the area of prose fiction publication, as well as challenges due to the continuing decline of the language[31]

The phrase Alba gu bràth "Scotland forever" is still used today as a catch-phrase or rallying cry.

Defunct dialects

All surviving dialects are Highland and/or Hebridean dialects. Dialects of Lowland Gaelic have become defunct since the demise of Galwegian Gaelic, originally spoken in Galloway, which seems to have been the last Lowland dialect and which survived into the Modern Period. By the 18th century Lowland Gaelic had been largely replaced by Lowland Scots across much of Lowland Scotland. According to a reference in The Carrick Covenanters by James Crichton,[32] the last place in the Lowlands where Scottish Gaelic was still spoken was the village of Barr in Carrick (only a few miles inland to the east of Girvan, but at one time very isolated). Crichton gives neither date nor details.[33]

There is, however, no evidence of a linguistic border following the topographical north-south differences. Similarly, there is no evidence from placenames of significant linguistic differences between, for example, Argyll and Galloway. Dialects on both sides of the Straits of Moyle (the North Channel) linking Scottish Gaelic with Irish are now extinct, though native speakers were still to be found on the Mull of Kintyre, Rathlin and in North East Ireland as late as the mid-20th century. Records of their speech show that Irish and Scottish Gaelic existed in a dialect chain with no clear language boundary.

Today, the closest tied Irish dialect with Highland Gaelic is Ulster Irish, spoken in County Donegal – most notably the Gaoth Dobhair Gaeltacht. Written Ulster Irish as well as common grammatical and vocabulary traits reflects more archaic Classical Gaelic still providing more of a solid link between the two languages than with Official Standard Irish, based on the dialects of southern provinces. However, to claim that Ulster Irish is a perfect intermediate between the Irish and Scottish forms of Gaelic still remains perhaps an exaggerated statement.

What is known as Scottish Gaelic is essentially that of the Gaelic spoken in The Outer Hebrides and on Skye. Generally speaking, the Gaelic spoken across The Western Isles (with perhaps exception to that of Arran and Kintyre) is similar enough to be classed as one major dialect group, although there is still regional variation, for example the pronunciation of the slender 'r' as [ð] in Lewis, where the Gaelic is thought to have a unique Nordic accent, and is described as being tonal.

Gaelic in Eastern and Southern Scotland is now largely defunct, although the dialects which were spoken in the east tended to preserve a more archaic tone, which had been lost further west. For example, Gaelic speakers in East Sutherland prefer to say Cà 'd robh tu m' oidhche a-raoir? (where were you about last night), rather than the more common càit an robh thu (oidhche) a-raoir?. Such dialects also retain the Classical Gaelic values of the stops, as do Manx and Irish Gaelic.

A certain number of these dialects, which are now defunct in Scotland, have been preserved and, indeed, re-established within the Nova Scotia Gaelic community. Those of particular note are the Morar and Lochaber dialects, the latter of which pronounces the broad or velarised l (l̪ˠ) as a w (similar to ʍ or w).[34]

Status

Number of speakers

| Year | Scottish population | Monolingual Gaelic speakers | Gaelic and English bilinguals | Total Gaelic language group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1755 | 1,265,380 | 289,798 | 22.9% | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| 1800 | 1,608,420 | 297,823 | 18.5% | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| 1881 | 3,735,573 | 231,594 | 6.1% | Unknown | Unknown | ||

| 1891 | 4,025,647 | 43,738 | 210,677 | 5.2% | |||

| 1901 | 4,472,103 | 28,106 | 202,700 | 4.5% | |||

| 1911 | 4,760,904 | 8,400 | 183,998 | 3.9% | |||

| 1921 | 4,573,471 | 9,829 | 148,950 | 3.3% | |||

| 1931 | 4,588,909 | 6,716 | 129,419 | 2.8% | |||

| 1951 | 5,096,415 | 2,178 | 93,269 | 1.8% | |||

| 1961 | 5,179,344 | 974 | 80,004 | 1.5% | |||

| 1971 | 5,228,965 | 477 | 88,415 | 1.7% | |||

| 1981 | 5,035,315 | — | 82,620 | 1.6% | 82,620 | 1.6% | |

| 1991 | 5,083,000 | — | 65,978 | 1.4% | 65,978 | 1.4% | |

| 2001 | 5,062,011 | — | 58,652 | 1.2% | 58,652 | 1.2% | |

| 2011 | 5,295,403 | — | 57,602 | 1.1% | 57,602 | 1.1% | |

The 1755–2001 figures are census data quoted by MacAulay.[35] The 2011 Gaelic speakers figures come from table KS206SC of the 2011 Census. The 2011 total population figure comes from table KS101SC. Note that the numbers of Gaelic speakers relate to the numbers aged 3 and over, and the percentages are calculated using those and the number of the total population aged 3 and over.

Distribution in Scotland

The 2011 UK Census showed a total of 57,375 Gaelic speakers in Scotland (1.1% of population over three years old).[36] Compared to the 2001 Census, there has been a diminution of approximately 1,300 people.[37] This is the smallest drop between censuses since the Gaelic language question was first asked in 1881, which the Scottish Government's language minister and Bord na Gaidhlig took as evidence that Gaelic's long decline has slowed.[38]

The main stronghold of the language continues to be the Outer Hebrides (Na h-Eileanan Siar), where the overall proportion of speakers is at 52.2%. Important pockets of the language also exist in the Highlands (5.4%) and in Argyll and Bute (4.0%). While mostly a language of small towns and rural areas, Gaelic's urban centre is Inverness where 4.9% speak the language. The locality with the largest absolute number is Glasgow with 5,878 such persons who make up over 10% of all of Scotland's Gaelic speakers.

Gaelic continues to decline in its traditional heartland. Between 2001 and 2011, the absolute number of Gaelic speakers fell sharply in the Western Isles (−1,745), Argyll & Bute (−694), and Highland (−634). The drop in Stornoway, the largest parish in the Western Isles by population, was especially acute, down from 57.5% of the population in 1991 to 43.4% in 2011.[39] The only parish outside the Western Isles over 40% Gaelic-speaking is Kilmuir in Northern Skye at 46%. Outside the Outer Hebrides the only areas with significant percentages of Gaelic speakers are the Inner Hebridean islands of Tiree (38.3%), Raasay (30.4%), Skye (29.4%), Lismore (26.9%), Colonsay (20.2%), and Islay (19.0%).

Continued decline in the traditional Gaelic heartland has been recently balanced by growth in others parts of Scotland. Between the 2001 and 2011 censuses, the number of Gaelic speakers rose in nineteen of the country's 32 council areas. The largest absolute gains were in Aberdeenshire (+526), North Lanarkshire (+305), Aberdeen City (+216), and East Ayrshire (+208). The largest relative gains were in Aberdeenshire (+0.19%), East Ayrshire (+0.18%), Moray (+0.16%), and Orkney (+0.13%).

Because of the continued decline of Gaelic in its traditional heartland, today no civil parish in Scotland has a proportion of Gaelic speakers greater than 65% (the highest value corresponds to Barvas, Lewis, with 64.1%). In addition, no civil parish on Mainland Scotland has a proportion of Gaelic speakers greater than 20% (the highest value corresponds to Ardnamurchan, Highland, with 19.3%). From a total of 871 civil parishes in Scotland, 7 have a proportion of Gaelic speakers greater than 50%, 14 have a proportion of Gaelic speakers greater than 25%, and 35 have a proportion of Gaelic speakers greater than 10%.

As with other Celtic languages, monolingualism is non-existent except among native-speaking children under school age in traditional Gàidhealtachd regions. In 2014, the census of pupils in Scotland showed 497 pupils in publicly funded schools had Gaelic as the main language at home, a drop of 18% from 606 students in 2010. During the same period, Gaelic medium education in Scotland has grown, with 3,583 pupils being educated in a Gaelic-immersion environment in 2014, up from 2,638 pupils in 2009.[40]

| Area | Gaelic Name | Number of Gaelic Speakers |

|---|---|---|

| Outer Hebrides | Eilean Siar | (52%) 14,248 |

| Highland | A' Ghaidhealtachd | (5%) 6,927 |

| Argyll and Bute | Earra-Ghaidheal agus Bòd | (4%) 3.500 |

| Glasgow | Glaschu | (1%) 5,726 |

| Edinburgh | Dun Eideann | (0.7%) 3,220 |

Writing system

Alphabet

Primitive Irish, the precursor to Old Irish, was written in a carved writing called Ogham. Ogham consisted of marks made above or below a horizontal line. With the advent of Christianity in the 5th century, the Latin alphabet was introduced to Ireland. The Goidelic languages have historically been part of a dialect continuum stretching from the south of Ireland, the Isle of Man, to the north of Scotland.

The modern Scottish Gaelic alphabet has 18 letters:

- A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, L, M, N, O, P, R, S, T, U.

The letter h, now mostly used to indicate lenition of a consonant, was in general not used in the oldest orthography, as lenition was instead indicated with a dot over the lenited consonant. The letters of the alphabet were traditionally named after trees, but this custom has fallen out of use.

Long vowels are marked with a grave accent (à, è, ì, ò, ù), indicated through digraphs (e.g. ao is [ɯː]) or conditioned by certain consonant environments (e.g. a u preceding a non-intervocalic nn is [uː]). Traditional spelling systems also use the acute accent on the letters á, é and ó to denote a change in vowel quality rather than length, but reform from within the Scottish schools system has abandoned these in parts of Gaelic speaking society.

Certain early sources used only an acute accent along the lines of Irish, particularly in the 18th century sources such as in the writings of Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair (1741–51) and the earliest editions (1768–90) of Duncan Ban MacIntyre.[41]

Orthography

Classical Gaelic was used as a literary language in Scotland until the 18th century. Orthographic divergence between Scottish Gaelic and Irish is the result of more recent orthographic reforms resulting in a pluricentric language situation.

The 1767 New Testament historically set the standard for Scottish Gaelic. Around the time of World War II, Irish spelling was reformed and the Official Standard or Caighdeán Oifigiúil introduced. Further reform in 1957 eliminated some of the silent letters that are still used in Scottish Gaelic. The 1981 Scottish Examination Board recommendations for Scottish Gaelic, the Gaelic Orthographic Conventions, were adopted by most publishers and agencies, although they remain controversial among some academics, most notably Ronald Black.[42]

The quality of consonants is indicated in writing by the vowels surrounding them. So-called "slender" consonants are palatalised while "broad" consonants are neutral or velarised. The vowels e and i are classified as slender, and a, o, and u as broad. The spelling rule known as caol ri caol agus leathann ri leathann ("slender to slender and broad to broad") requires that a word-medial consonant or consonant group followed by a written i or e be also preceded by an i or e; and similarly if followed by a, o or u be also preceded by an a, o, or u. Consonant quality (palatalised or non-palatalised) is then indicated by the vowels written adjacent to a consonant, and the spelling rule gives the benefit of removing possible uncertainty about consonant quality at the expense of adding additional purely graphic vowels that may not be pronounced. For example, compare the t in slàinte [s̪lˠ̪aːɲtʲə] with the t in bàta [paːʰt̪ə].

The rule has no effect on the pronunciation of vowels. For example, plurals in Gaelic are often formed with the suffix -an, for example, bròg [prɔːk] (shoe) / brògan [prɔːkən] (shoes). But because of the spelling rule, the suffix is spelled -ean (but pronounced the same) after a slender consonant, as in taigh [tʰɤj] (house) / taighean [tʰɛhən] (houses) where the written e is purely a graphic vowel inserted to conform with the spelling rule because an i precedes the gh.

In changes promoted by the Scottish Examination Board from 1976 onwards, certain modifications were made to this rule. For example, the suffix of the past participle is always spelled -te, even after a broad consonant, as in togte "raised" (rather than the traditional togta).

Where pairs of vowels occur in writing, it is sometimes unclear which vowel is to be pronounced and which vowel has been introduced to satisfy this spelling rule.

Unstressed vowels omitted in speech can be omitted in informal writing. For example:

- Tha mi an dòchas. ("I hope.") > Tha mi 'n dòchas.

Once Gaelic orthographic rules have been learned, the pronunciation of the written language is in general quite predictable. However learners must be careful not to try to apply English sound-to-letter correspondences to written Gaelic, otherwise mispronunciations will result. Gaelic personal names such as Seònaid [ˈʃɔːnɛdʲ] are especially likely to be mispronounced by English speakers.

Scots English orthographic rules have also been used at various times in Gaelic writing. Notable examples of Gaelic verse composed in this manner are the Book of the Dean of Lismore and the Fernaig manuscript.

Pronunciation

Most varieties of Gaelic have between 8 and 9 vowel phonemes (/i e ɛ a ɔ o u ɤ ɯ/) that can be either long or short. There are also two reduced vowels ([ə ɪ]) which only occur short. Although some vowels are strongly nasal, instances of distinctive nasality are rare. There are about nine diphthongs and a few triphthongs.

Most consonants have both palatal and non-palatal counterparts, including a very rich system of liquids, nasals and trills (i.e. 3 contrasting l sounds, 3 contrasting n sounds and 3 contrasting r sounds). The historically voiced stops [b d̪ ɡ] have lost their voicing, so the phonemic contrast today is between unaspirated [p t̪ k] and aspirated [pʰ t̪ʰ kʰ]. In many dialects, these stops may however gain voicing through secondary articulation through a preceding nasal, for examples doras [t̪ɔɾəs̪] "door" but an doras "the door" as [ən̪ˠ d̪ɔɾəs̪] or [ə n̪ˠɔɾəs̪].

In some fixed phrases, these changes are shown permanently, as the link with the base words has been lost, as in an-dràsta "now", from an tràth-sa "this time/period".

In medial and final position, the aspirated stops are preaspirated rather than aspirated.

Grammar

Scottish Gaelic is an Indo-European language with an inflecting morphology, a verb–subject–object word order and two grammatical genders.

Noun inflection

Gaelic nouns inflect for four cases (nominative/accusative, vocative, genitive and dative) and three numbers (singular, dual and plural).

They are also normally either classed as masculine or feminine. A small number of words that used to belong to the neuter class show some degree of gender confusion. For example, in some dialects am muir "the sea" behaves as a masculine noun in the nominative case, but as a feminine noun in the genitive (na mara).

Nouns are marked for case in a number of ways, most commonly by involving various combinations of lenition, palatalization and suffixation.

Verb inflection

There are 12 irregular verbs.[43] Most other verbs are derived following a fully predictable paradigm although polysyllabic verbs ending in laterals can deviate from this paradigm as they show syncopation.

There are:

- Three persons: 1st, 2nd, 3rd

- Three numbers: singular, dual and plural

- Two voices: traditionally called active and passive, but actually personal and impersonal.

- Three non-composed combined TAM forms expressing tense, aspect and mood, i.e. non-past (future-habitual), conditional (future of the past), and past (preterite); several composed TAM forms, such as pluperfect, future perfect, present perfect, present continuous, past continuous, conditional perfect, etc. Two verbs, bi, used to attribute a notionally temporary state, action, or quality to the subject, and is, used to show a notional permanent identity or quality, have non-composed present and non-past tense forms: (bi) tha [perfective present], bì/bithidh [imperfective non-past]; (is) is imperfective non-past.

- Three modes: independent (used in affirmative main clause verbs), relative (used in verbs in affirmative relative clauses), and dependent (used in subordinate clauses, anti-affirmative relative clauses, and anti-affirmative main clauses)

Word order

Word order is strictly verb–subject–object, including questions, negative questions and negatives. Only a restricted set of preverb particles may occur before the verb.

Official recognition

Scottish Parliament

Fàilte gu stèisean Dùn [sic] Èideann[44]

("Welcome to Edinburgh station")

Gaelic has long suffered from its lack of use in educational and administrative contexts and was long suppressed.[45] It has not received the same degree of official recognition from the UK Government as Welsh. With the advent of devolution, however, Scottish matters have begun to receive greater attention, and it has achieved a degree of official recognition when the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act was enacted by the Scottish Parliament on 21 April 2005.

The key provisions of the Act are:[46]

- Establishing the Gaelic development body, Bòrd na Gàidhlig, (BnG), on a statutory basis with a view to securing the status of the Gaelic language as an official language of Scotland commanding equal respect to the English language and to promote the use and understanding of Gaelic.

- Requiring BnG to prepare a National Gaelic Language Plan for approval by Scottish Ministers.

- Requiring BnG to produce guidance on Gaelic Education for education authorities.

- Requiring public bodies in Scotland, both Scottish public bodies and cross border public bodies insofar as they carry out devolved functions, to develop Gaelic language plans in relation to the services they offer, if requested to do so by BnG.

Following a consultation period, in which the government received many submissions, the majority of which asked that the bill be strengthened, a revised bill was published with the main improvement that the guidance of the Bòrd is now statutory (rather than advisory).

In the committee stages in the Scottish Parliament, there was much debate over whether Gaelic should be given 'equal validity' with English. Due to Executive concerns about resourcing implications if this wording was used, the Education Committee settled on the concept of 'equal respect'. It is not clear what the legal force of this wording is.

The Act was passed by the Scottish Parliament unanimously, with support from all sectors of the Scottish political spectrum on 21 April 2005. Some commentators, such as Éamonn Ó Gribín (2006) argue that the Gaelic Act falls so far short of the status accorded Welsh that one would be foolish or naïve to believe that any substantial change will occur in the fortunes of the language as a result of Bòrd na Gàidhlig's efforts.[47]

Under the provisions of the 2005 Act, it will ultimately fall to BnG to secure the status of the Gaelic language as an official language of Scotland.

On 10 December 2008 to celebrate the 60th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Scottish Human Rights Commission had the UDHR translated into Gaelic for the first time.[48]

Education

| Year | Number of students in Gaelic medium education | Percentage of all students in Scotland |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2,480 | 0.35% |

| 2006 | 2,535 | 0.36%[49] |

| 2007 | 2,601 | 0.38% |

| 2008 | 2,766 | 0.4%[50] |

| 2009 | 2,638 | 0.39%[51] |

| 2010 | 2,647 | 0.39%[52] |

| 2011 | 2,929 | 0.44%[53] |

| 2012 | 2,871 | 0.43%[54] |

| 2013 | 2,953 | 0.44%[55] |

| 2014 | 3,583 | 0.53%[56] |

| 2015 | 3,660 | 0.54%[57] |

The Education (Scotland) Act 1872, which completely ignored Gaelic, and led to generations of Gaels being forbidden to speak their native language in the classroom, is now recognised as having dealt a major blow to the language. People still living can recall being beaten for speaking Gaelic in school.[58] The first modern solely Gaelic-medium secondary school, Sgoil Ghàidhlig Ghlaschu ("Glasgow Gaelic School"), was opened at Woodside in Glasgow in 2006 (61 partially Gaelic-medium primary schools and approximately a dozen Gaelic-medium secondary schools also exist). According to Bòrd na Gàidhlig, a total of 2,092 primary pupils were enrolled in Gaelic-medium primary education in 2008–09, as opposed to 24 in 1985.[59]

In Nova Scotia, Canada, there are somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 native speakers, most of whom are now elderly. In May 2004, the provincial government announced the funding of an initiative to support the language and its culture within the province. Several public schools in Northeastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton offer Gaelic classes as part of the high-school curriculum.[60]

Maxville Public School in Maxville, Glengarry, Ontario, Canada offers Scottish Gaelic lessons weekly.

In Prince Edward Island, Canada, the Colonel Gray High School is now offering two courses in Gaelic, an introductory and an advanced course; both language and history are taught in these classes. This is the first recorded time that Gaelic has ever been taught as an official course on Prince Edward Island.

The UK government has ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in respect of Gaelic. Along with Irish and Welsh, Gaelic is designated under Part III of the Charter, which requires the UK Government to take a range of concrete measures in the fields of education, justice, public administration, broadcasting and culture.

The Columba Initiative, also known as colmcille (formerly Iomairt Cholm Cille), is a body that seeks to promote links between speakers of Scottish Gaelic and Irish.

However, given there are no longer any monolingual Gaelic speakers,[61] following an appeal in the court case of Taylor v Haughney (1982), involving the status of Gaelic in judicial proceedings, the High Court ruled against a general right to use Gaelic in court proceedings.[62]

European Union

In October 2009, a new agreement was made which allows Scottish Gaelic to be used formally between Scottish Government ministers and European Union officials. The deal was signed by Britain's representative to the EU, Sir Kim Darroch, and the Scottish government. This does not give Scottish Gaelic official status in the EU, but gives it the right to be a means of formal communications in the EU's institutions. The Scottish government will have to pay for the translation from Gaelic to other European languages. The deal was received positively in Scotland; Secretary of State for Scotland Jim Murphy said the move was a strong sign of the UK government's support for Gaelic. He said that "Allowing Gaelic speakers to communicate with European institutions in their mother tongue is a progressive step forward and one which should be welcomed". Culture Minister Mike Russell said that "this is a significant step forward for the recognition of Gaelic both at home and abroad and I look forward to addressing the council in Gaelic very soon. Seeing Gaelic spoken in such a forum raises the profile of the language as we drive forward our commitment to creating a new generation of Gaelic speakers in Scotland."[63]

The Scottish Gaelic used in Machine-readable British passports differs from Irish passports in places. "Passport" is rendered Cead-siubhail (in Irish, Pas); "The European Union", Aonadh Eòrpach (in Irish, An tAontas Eorpach), while "Northern Ireland" is Èirinn a Tuath in Gaelic (the Irish equivalent is Tuaisceart Éireann).

Media

The BBC operates a Gaelic-language radio station Radio nan Gàidheal as well as a television channel, BBC Alba. Launched on 19 September 2008, BBC Alba is widely available in the UK (on Freeview, Freesat, Sky and Virgin Media). It also broadcasts across Europe on the Astra 2 satellites.[64] The channel is being operated in partnership between BBC Scotland and MG Alba – an organisation funded by the Scottish Government, which works to promote the Gaelic language in broadcasting.[65] The ITV franchise in central Scotland, STV Central, produces a number of Scottish Gaelic programmes for both BBC Alba and its own main channel.[65]

Until BBC Alba was broadcast on Freeview, viewers were able to receive the channel TeleG, which broadcast for an hour every evening. Upon BBC Alba's launch on Freeview, it took the channel number than was previously assigned to TeleG.

There are also television programmes in the language on other BBC channels and on the independent commercial channels, usually subtitled in English. The ITV franchise in the north of Scotland, STV North (formerly Grampian Television) produces some non-news programming in Scottish Gaelic.

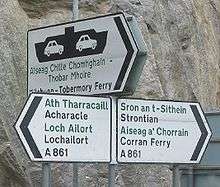

Signage

Bilingual road signs, street names, business and advertisement signage (in both Gaelic and English) are gradually being introduced throughout Gaelic-speaking regions in the Highlands and Islands, including Argyll. In many cases, this has simply meant re-adopting the traditional spelling of a name (such as Ràtagan or Loch Ailleart rather than the anglicised forms Ratagan or Lochailort respectively).

Bilingual railway station signs are now more frequent than they used to be. Practically all of the stations in the highland area use both English and Gaelic, and the spreading of bilingual station signs is becoming ever-more frequent in the Lowlands of Scotland, including areas where Gaelic has not been spoken for a long time.

While this has been welcomed by many supporters of the language as a means of raising its profile as well as securing its future as a 'living language' (i.e. allowing people to use it to navigate from A to B in place of English) and creating a sense of place, recently revealed roadsigns for Castletown in Caithness in the Highlands indicate The Highland Council's intention to introduce bilingual signage into all areas of the Highlands have caused some controversy.[66]

The Ordnance Survey has acted in recent years to correct many of the mistakes that appear on maps. They announced in 2004 that they intended to correct them and set up a committee to determine the correct forms of Gaelic place names for their maps.

Canada

The Atlantic Canadian province of Nova Scotia is home to 1,275 Gaelic speakers as of 2011,[67] of whom 300 claim to have Gaelic as their "mother tongue".[68] The Nova Scotia government maintains an Office of Gaelic Affairs which works to promote the Gaelic language, culture, and tourism. As in Scotland, bilingual street signs are in place in areas of North-Eastern Nova Scotia and in Cape Breton. Nova Scotia also has the Comhairle na Gàidhlig (The Gaelic Council of Nova Scotia), a non-profit society dedicated to the maintenance and promotion of the Gaelic language and culture in Maritime Canada.

Maxville Public School in Maxville, Glengarry, Ontario, Canada offers Scottish Gaelic lessons weekly.

In Prince Edward Island, the Colonel Gray High School now offers both an introductory and an advanced course in Gaelic; both language and history are taught in these classes. This is the first recorded time that Gaelic has ever been taught as an official course on Prince Edward Island.

The province of British Columbia is host to the Comunn Gàidhlig Bhancoubhair (The Gaelic Society of Vancouver), the Vancouver Gaelic Choir, the Victoria Gaelic Choir, as well as the annual Gaelic festival Mòd Vancouver. The city of Vancouver's Scottish Cultural Centre also holds seasonal Scottish Gaelic evening classes.

Church

In the Western Isles, the isles of Lewis, Harris and North Uist have a Presbyterian majority (largely Church of Scotland – Eaglais na h-Alba in Gaelic, Free Church of Scotland and Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland.) The isles of South Uist and Barra have a Catholic majority. All these churches have Gaelic-speaking congregations throughout the Western Isles.

There are Gaelic-speaking congregations in the Church of Scotland, mainly in the Highlands and Islands, but also in Edinburgh and Glasgow. Notable city congregations with regular services in Gaelic are St Columba's Church, Glasgow and Greyfriars Tolbooth & Highland Kirk, Edinburgh. Leabhar Sheirbheisean – a shorter Gaelic version of the English-language Book of Common Order – was published in 1996 by the Church of Scotland.

The relationship between the Church and Gaelic has not always been an easy one. The widespread use of English in worship has often been suggested as one of the historic reasons for the decline of Gaelic. Whilst the Church of Scotland is supportive today, there is, however, an increasing difficulty in being able to find Gaelic-speaking ministers. The Free Church also recently announced plans to reduce their Gaelic provision by abolishing Gaelic-language communion services, citing both a lack of ministers and a desire to have their congregations united at communion time.[69]

Sport

The most notable use of the language in sport is that of the Camanachd Association, the shinty society, who have a bilingual logo.

In the mid-1990s, the Celtic League started a campaign to have the word "Alba" on the Scottish football and rugby union tops. Since 2005, the SFA have supported the use of Scottish Gaelic on their teams' strip in recognition of the language's revival in Scotland.[70] However, the SRU is still being lobbied to have "Alba" on the national rugby strip.[71][72]

Some sports coverage, albeit at a small level, takes place in Scottish Gaelic broadcasting.

Personal names

Some traditional Gaelic names have no direct equivalents in English: Oighrig, which is normally rendered as Euphemia (Effie) or Henrietta (Etta) (formerly also as Henny or even as Harriet), or, Diorbhal, which is "matched" with Dorothy, simply on the basis of a certain similarity in spelling; Gormul, for which there is nothing similar in English, and it is rendered as Gormelia or even Dorothy; Beathag, which is "matched" with Becky (> Rebecca) and even Betsy, or Sophie. Many of these traditional Gaelic-only names are now regarded as old-fashioned, and hence are rarely or never used.

Some names have come into Gaelic from Old Norse; for example, Somhairle ( < Somarliðr), Tormod (< Þórmóðr), Ranald or Raonull (< Rögnvaldr), Torcuil (< Þórkell, Þórketill), Ìomhar (Ívarr). These are conventionally rendered in English as Sorley (or, historically, Somerled), Norman, Ronald or Ranald, Torquil and Iver (or Evander). Somhairle has no modern equivalent in the Nordic countries. Tormod is a common male name in Norway but not in Denmark and Sweden. Torcuil is spelled Torgil and is a male name in the Nordic countries. It is still used but not so common. Iomhar is spelled Ivar in the Nordic countries and a fairly common male name in Sweden, especially among older males.

Some traditional Gaelic names have become so well-known, that English versions of them are used outside Gaelic-speaking areas. Also, Gaelic has its own version of European-wide names which also have English forms. Names which fall into one or other of these classes are: Ailean (Alan), Aonghas (Angus), Dòmhnall (Donald), Donnchadh (Duncan), Coinneach (Kenneth), Murchadh (Murdo), Iain (John), Alasdair (Alexander), Uilleam (William), Catrìona (Catherine), Raibeart (Robert), Ranald (Ronald), Cairistìona (Christina), Anna (Ann), Màiri (Mary), Seumas (James), Pàdraig (Patrick) and Tòmas (Thomas). The well-known name Hamish, and the recently established Mhairi (pronounced [vaːri]) come from the Gaelic for, respectively, James, and Mary, but derive from the form of the names as they appear in the vocative case: Seumas (James) (nom.) → Sheumais (voc.), and, Màiri (Mary) (nom.) → Mhàiri (voc.).

Surnames

The most common class of Gaelic surnames are those beginning with mac (Gaelic for "son"), such as MacGillEathain (MacLean). The female form is nic (Gaelic for "daughter"), so Catherine MacPhee is properly called in Gaelic, Caitrìona Nic a' Phì (strictly, "nic" is a contraction of the Gaelic phrase nighean mhic, meaning "daughter of the son", thus Nic Dhomhnuill, really means "daughter of MacDonald" rather than "daughter of Donald"). Although there is a common misconception that mac means "son of", the "of" part actually comes from the genitive form of the patronymic that follows the prefix "Mac", e.g., in the case of MacNéill, Néill ("of Neil") is the genitive form of Niall ("Neil").

Several colours give rise to common Scottish surnames: bàn (Bain – white), ruadh (Roy – red), dubh (Dow, Duff – black), donn (Dunn – brown), buidhe (Bowie – yellow).

Loanwords

The majority of the vocabulary of Scottish Gaelic is native Celtic. There are a large number of borrowings from Latin, (muinntir, Didòmhnaich from (dies) dominica), ancient Greek, especially in the religious domain (eaglais, Bìoball from Ekklesia and Biblia), Norse (eilean from eyland, sgeir from sker), Hebrew (Sàbaid from shabbáth, Aba), French (seòmar from chambre) and Scots (aidh, bramar).

In common with other Indo-European languages, the neologisms which are coined for modern concepts are typically based on Greek or Latin, although written in Gaelic orthography; television, for instance, becomes telebhisean and computer becomes coimpiùtar. Although native speakers frequently use an English word for which there is a perfectly good Gaelic equivalent, they will, without thinking, simply adopt the English word and use it, applying the rules of Gaelic grammar, as the situation requires. With verbs, for instance, they will simply add the verbal suffix (-eadh, or, in Lewis, -igeadh, as in, "Tha mi a' watcheadh (Lewis, "watchigeadh") an telly" (I am watching the television), instead of "Tha mi a' coimhead air an telebhisean". This was remarked upon by the minister who compiled the account covering the parish of Stornoway in the New Statistical Account of Scotland, published over 170 years ago. It has even gone so far as the verb Backdatigeadh. However, as Gaelic medium education grows in popularity, a newer generation of literate Gaels is becoming more familiar with modern Gaelic vocabulary.

Going in the other direction, Scottish Gaelic has influenced the Scots language and English, particularly Scottish Standard English. Loanwords include: whisky, slogan, brogue, jilt, clan, trousers, gob, as well as familiar elements of Scottish geography like ben (beinn), glen (gleann) and loch. Irish has also influenced Lowland Scots and English in Scotland, but it is not always easy to distinguish its influence from that of Scottish Gaelic.[73]

See also List of English words of Scottish Gaelic origin.

There are also many Brythonic influences on Scottish Gaelic. Scottish Gaelic contains a number of apparently P-Celtic loanwords, but as there is a far greater overlap in terms of Celtic vocabulary, than with English, it is not always possible to disentangle P and Q Celtic words. However some common words such as monadh = Welsh mynydd Cumbric *monidh are particularly evident. Often the Brythonic influence on Scottish Gaelic is indicated by considering the Irish Gaelic usage which is not likely to have been influenced so much by Brythonic. In particular, the word srath (Anglicised as "Strath") is a native Goidelic word, but its usage appears to have been modified by the Brythonic cognate ystrad whose meaning is slightly different.

Common words and phrases with Irish and Manx equivalents

| Scottish Gaelic | Irish | Manx Gaelic | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| sinn [ʃiːɲ] | muid/sinn [mˠidʲ / ʃiɲ] | shin [ʃin] | we |

| aon [ɯːn] | aon [eːn] | nane [neːn] | one |

| mòr [moːɾ] | mór [mˠoːɾ] / [mˠuəɾ] | mooar [muːɾ] | big |

| iasg [iəs̪k] | iasc [iəsk] | eeast [jiːs] | fish |

| cù [kʰuː] (madadh [mat̪əɣ]) |

madra [mˠadɾə] gadhar [ gˠəiɾ] (cú [kʰuː]) |

moddey [mɔːdə] (coo [kʰuː]) |

dog |

| grian [kɾʲiən] | grian [gˠɾʲiən] | grian [gridn] | sun |

| craobh [kʰɾɯːv] (crann [kʰɾaun̪ˠ]) |

crann [kʰɾa(u)nˠ] | billey [biʎə] | tree |

| cadal [kʰat̪əl̪ˠ] | codail [kʰodəlʲ] | cadley [kʲadlə] | sleep (verb) |

| ceann [kʲaun̪ˠ] | ceann [kʲaunˠ] / [kʲa:nˠ] | kione [kʲo:n̪ˠ] | head |

| cha do dh'òl thu [xa t̪ə ɣɔːl̪ˠ u] | Ní d'ól tú [n̠ʲi: d̪ˠo:l̪ˠ t̪ˠu:] | cha diu oo [xa deu u] | you did not drink |

| bha mi a' faicinn [va mi fɛçkʲɪɲ] | Bhí mé ag feiceáil [wi: mʲe: əg fʲɛca:il̠ʲ] (bhíos ag feiscint [wi:ɔsˠ əg fʲɛʃcin̠ʲt]) |

va mee fakin [vɛ mə faːɣin] | I was seeing |

| Slàinte [s̪l̪ ˠaːɲtʲə] | Sláinte | Slaynt | health, cheers! (toast) |

Note: Items in brackets denote archaic or dialectal forms

Qualifications in the language

Examinations

The Scottish Qualifications Authority offer two streams of Gaelic examination across all levels of the syllabus: Gaelic for learners (equivalent to the modern foreign languages syllabus) and Gaelic for native speakers (equivalent to the English syllabus).

An Comunn Gàidhealach performs assessment of spoken Gaelic, resulting in the issue of a Bronze Card, Silver Card or Gold Card. Syllabus details are available on An Comunn's website. These are not widely recognised as qualifications, but are required for those taking part in certain competitions at the annual mods.

Higher and further education

A number of Scottish and some Irish universities offer full-time degrees including a Gaelic language element, usually graduating as Celtic Studies.

St. Francis Xavier University, the Gaelic College of Celtic Arts and Crafts and Cape Breton University (formerly University College Of Cape Breton) in Nova Scotia, Canada also offer a Celtic Studies degrees and/or Gaelic language programs.

In Russia the Moscow State University offers Gaelic language, history and culture courses.

Courses at the University of the Highlands and Islands

The University of the Highlands and Islands offers a range of Gaelic courses at Cert HE, Dip HE, BA (ordinary), BA (Hons) and MA, and offers opportunities for postgraduate research through the medium of Gaelic. The majority of these courses are available as residential courses at Sabhal Mòr Ostaig. A number of other colleges offer the one-year certificate course, which is also available on-line (pending accreditation).

Lews Castle College's Benbecula campus offers an independent 1 year course in Gaelic and Traditional Music (FE, SQF level 5/6).

See also

- Languages of Scotland

- Scottish English

- Scots language (Lowland Scots)

- Scottish Gaelic literature

- An Comunn Gàidhealach

- Book of Deer

- Bungi creole

- Canadian Gaelic

- Clì Gàidhlig

- Differences between Scottish Gaelic and Irish

- Gaelic broadcasting in Scotland

- Gaelic Digital Service

- Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005

- Gaelic medium education in Scotland

- Gaelic music

- Gaelic revival

- Gaelic road signs in Scotland

- Gaelic Society of Moscow

- Gaelicisation

- Galwegian Gaelic

- Gàidhealtachd

- Goidelic substrate hypothesis

- Irish language

- List of Celtic language media

- List of Scottish Gaelic place names

- List of television channels in Celtic languages

- Nancy Dorian

- The Mòd

- William J. Watson

References

- 1 2 3 2011 Census of Scotland, Table QS211SC. Viewed 30 May 2014.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Scottish Gaelic". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Scotland's Census Results Online (SCROL), Table UV12. Viewed 30 May 2014.

- ↑ Scottish Government, "A’ fàs le Gàidhlig", 26 September 2013. Viewed 30 May 2014.

- ↑ List of declarations made with respect to treaty No. 148 from the Council of Europe.

- ↑ "Official text of the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005". Statutelaw.gov.uk. 2011-05-26. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- ↑ Statistics Canada, 2011 NHS Survey

- ↑ "2011 Census of Canada, Topic-based tabulations, Detailed mother tongue (192)". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "Gaelic: definition of Gaelic in Oxford dictionary (British & World English)". Oxforddictionaries.com. 2013-11-06. Retrieved 2013-11-13.

- ↑ "Irish vs Gaelic". YouTube. 2012-04-12. Retrieved 2013-11-13.

- ↑ Companion to the Oxford English Dictionary, Tom McArthur, Oxford University Press, 1994

- ↑ Jones, Charles (1997). The Edinburgh history of the Scots language. Edinburgh University Press. p. 551. ISBN 978-0-7486-0754-9.

- ↑ Nora Kershaw Chadwick, Myles Dyllon (1972). The Celtic Realms. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7607-4284-6.

- ↑ Clarkson, pp. 238–244

- ↑ Broun, "Dunkeld", Broun, "National Identity", Forsyth, "Scotland to 1100", pp. 28–32, Woolf, "Constantine II"; cf. Bannerman, "Scottish Takeover", passim, representing the "traditional" view.

- ↑ Withers, Charles W. J. (1984). Gaelic in Scotland, 1698–1981. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers Ltd. pp. 16–18. ISBN 0859760979.

- ↑ http://www.euppublishing.com/doi/abs/10.3366/shr.2013.0178

- ↑ Clarkson, p. 276

- ↑ Colm Ó Baoill, “The Scots–Gaelic interface,” in Charles Jones, ed., The Edinburgh History of the Scots Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1997, p. 554

- 1 2 Withers, p. 19

- ↑ Magnusson, p. 68

- ↑ MacArthur, Margaret (1874). History of Scotland. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 33.

- 1 2 Withers, pp. 19–23

- ↑ Whyte, Ian D. (2013). Scotland before the Industrial Revolution. Routledge. p. 57.

- ↑ Bower, Walter (1990). S. Taylor; D. E. R. Watt; B. Scott, eds. "Scotichronicon". Aberdeen.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ Ó Baoill, p. 553–6

- ↑ Withers, Charles W. J. (1988). "The Geographical History of Gaelic in Scotland". In Colin H. Williams. Language in Geographic Context. p. 139.

- 1 2 Mackenzie, Donald W. (1990–92). "The Worthy Translator: How the Scottish Gaels got the Scriptures in their own Tongue". Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness. 57: 168–202.

- ↑ Ross, David (2002). Scotland: History of a Nation. Geddes & Grosset.

- ↑ Hunter, James (1976). The Making of the Crofting Community. pp. 178–9.

- ↑ Storey, John (2011) "Contemporary Gaelic fiction: development, challenge and opportunity" Lainnir a’ Bhùirn' – The Gleaming Water: Essays on Modern Gaelic Literature, edited by Emma Dymock & Wilson McLeod, Dunedin Academic Press.

- ↑ Printed at the Office of Messrs. Arthur Guthrie and Sons Ltd., 49 Ayr Road, Cumnock

- ↑ For further discussion on the subject of Gaelic in the South of Scotland, see articles Gàidhlig Ghallghallaibh agus Alba-a-Deas ("Gaelic of Galloway and Southern Scotland") and Gàidhlig ann an Siorramachd Inbhir-Àir ("Gaelic in Ayrshire") by Garbhan MacAoidh, published in GAIRM Numbers 101 and 106.

- ↑ Kennedy, Michael (2002). Gaelic in Nova Scotia: An Economic, Cultural and Social Impact Study (PDF). Province of Nova Scotia. p. 131. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ↑ MacAulay, Donald (1992). The Celtic Languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 141. ISBN 0521231272. – quoting census data. No data recorded for monolingual Gaelic speakers from 1981

- ↑ 2011 Census of Scotland, Table QS211SC. Viewed 23 June 2014.

- ↑ Scotland's Census Results Online (SCROL), Table UV12. Viewed 23 June 2014.

- ↑ "Census shows decline in Gaelic speakers 'slowed'". BBC News Online. 26 September 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ↑ "Census shows Gaelic declining in its heartlands". BBC News Online. 15 November 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ↑ "Pupil Census Supplementary Data". The Scottish Government. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ↑ O'Rahilly, T F, Irish Dialects Past and Present. Brown and Nolan 1932, ISBN 0-901282-55-3, p. 19

- ↑ The Board of Celtic Studies Scotland (1998) Computer-Assisted Learning for Gaelic: Towards a Common Teaching Core. The orthographic conventions were revised by the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) in 2005: "Gaelic Orthographic Conventions 2005" (PDF). SQA publication BB1532. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

- ↑ Cox, Richard Brìgh nam Facal (1991) Roinn nan Cànan Ceilteach ISBN 0-903204-21-5

- ↑ This should of course be spelt Dhùn, not Dùn

- ↑ See Kenneth MacKinnon (1991) Gaelic: A Past and Future Prospect. Edinburgh: The Saltire Society.

- ↑ Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005.

- ↑ Williams, Colin H., Legislative Devolution and Language Regulation in the United Kingdom, Cardiff University

- ↑ "Latest News – SHRC". Scottish Human Rights Commission. 2008-10-12. Retrieved 2013-11-13.

- ↑ Pupils in Scotland, 2006 from scot.gov.uk. Published February 2007, Scottish Government.

- ↑ Pupils in Scotland, 2008 from scot.gov.uk. Published February 2009, Scottish Government.

- ↑ Pupils in Scotland, 2009 from scotland.gov.uk. Published 27 November 2009, Scottish Government.

- ↑ "Scottish Government: Pupils Census, Supplementary Data". Scotland.gov.uk. 2011-06-14. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- ↑ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2011 Spreadsheet published 3 February 2012 (Table 1.13)

- ↑ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2012 Spreadsheet published 11 December 2012 (Table 1.13)

- ↑ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2013 Spreadsheet (Table 1.13)

- ↑ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2014 Spreadsheet (Table 1.13)

- ↑ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2015 Spreadsheet (Table 1.13)

- ↑ Pagoeta, Mikel Morris (2001). Europe Phrasebook. Lonely Planet. p. 416. ISBN 1-86450-224-X.

- ↑ "Gael-force wind of change in the classroom". The Scotsman. 2008-10-29. Retrieved 2011-06-08.

- ↑ "Gaelic core class increasingly popular in Nova Scotia". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 2015-01-26. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ↑ "UK Ratification of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Working Paper 10 – R.Dunbar, 2003" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- ↑ Archived 1 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "EU green light for Scots Gaelic". BBC News Online. 7 October 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- ↑ BBC Reception advice – BBC Online

- 1 2 About BBC Alba, from BBC Online

- ↑ "Caithness councillors harden resolve against Gaelic signs". The Press and Journal. 24 October 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ↑ "National Household Survey Profile, Nova Scotia, 2011". 2.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- ↑ "2011 Census of Canada: Topic-based tabulations, Detailed Mother Tongue, Nova Scotia". 2.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- ↑ MacLeod, Murdo (6 January 2008). "Free Church plans to scrap Gaelic communion service". The Scotsman. Edinburgh.

- ↑ "Gaelic added to Scotland strips". BBC News Online. 24 August 2006. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ "Scottish Rugby Union: "Put 'Alba' on Scottish Ruby Shirt"". Facebook. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- ↑ "BBC Alba – Gàidhlig air lèintean rugbaidh na h-Alba" (in Scottish Gaelic).

- ↑ Macbain, Alexander (1896). An Etymological Dictionary of the Gaelic Language (Digitized facsimile ed.). BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-116-77321-7.

Resources

- Gillies, H. Cameron. (1896). Elements of Gaelic Grammar. Vancouver: Global Language Press (reprint 2006), ISBN 1-897367-02-3 (hardcover), ISBN 1-897367-00-7 (paperback)

- Gillies, William. (1993). "Scottish Gaelic", in Ball, Martin J. and Fife, James (eds). The Celtic Languages (Routledge Language Family Descriptions). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28080-X (paperback), p. 145–227

- Lamb, William. (2001). Scottish Gaelic. Munich: Lincom Europa, ISBN 3-89586-408-0

- MacAoidh, Garbhan. (2007). Tasgaidh – A Gaelic Thesaurus. Lulu Enterprises, N. Carolina

- McLeod, Wilson (ed.). (2006). Revitalising Gaelic in Scotland: Policy, Planning and Public Discourse. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press, ISBN 1-903765-59-5

- Robertson, Charles M. (1906–07). "Scottish Gaelic Dialects", The Celtic Review, vol 3 pp. 97–113, 223–39, 319–32.

- Withers, Charles W. J. (1984). Gaelic in Scotland, 1689–1984. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers Ltd. ISBN 0-85976-097-9.

External links

| Scottish Gaelic edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scottish Gaelic language. |

| For a list of words relating to Scottish Gaelic, see the Scottish Gaelic language category of words in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikibooks has more on the topic of: Scottish Gaelic |

| Wikivoyage has a phrasebook for Scottish Gaelic. |

- BBC Alba – Scottish Gaelic language, music and news

- Bòrd na Gàidhlig – Scotland's Gaelic-language Board

- Gaelic Resource Database – founded by Comhairle nan Eilean Siar

- Scottish Gaelic Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- Faclair Dwelly air Loidhne – Dwelly's Gaelic dictionary online

- Gàidhlig air an Lìon – Sabhal Mòr Ostaig's links to pages in and about Scottish Gaelic

- Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies – Census information from 1881 to the present, 27 volumes covering all Gaelic-speaking regions

- Goidelic Dictionaries

- Pàrlamaid na h-Alba: Gàidhlig – Scottish Parliament site in Gaelic

- Gaelic psalms at Back Free Church, Isle Of Lewis (6:29)

- Sermons in Scottish Gaelic, Back Free Church, Back, Isle of Lewis

- Comhairle na Gàidhlig – The Gaelic Council of Nova Scotia (Canada)

- Comunn Gàidhlig Bhancoubhair – The Gaelic Society of Vancouver (Canada)

- DASG - The Digital Archive of Scottish Gaelic