Frenzy

| Frenzy | |

|---|---|

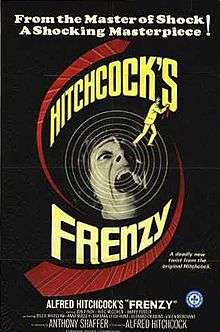

theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Produced by | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Screenplay by | Anthony Shaffer |

| Based on |

Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square by Arthur La Bern |

| Starring |

Jon Finch Alec McCowen Barry Foster |

| Music by | Ron Goodwin |

| Cinematography |

Gilbert Taylor Leonard J. South |

| Edited by | John Jympson |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2 million[1] |

| Box office | $12.6 million[2] |

Frenzy is a 1972 British thriller-psychological horror film directed by Alfred Hitchcock. The penultimate feature film of his extensive career, it is often considered by critics and scholars to be his last great film before his death. The screenplay by Anthony Shaffer was based on the novel Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square by Arthur La Bern. The film stars Jon Finch, Alec McCowen, and Barry Foster and features Billie Whitelaw, Anna Massey, Barbara Leigh-Hunt, Bernard Cribbins and Vivien Merchant. The original music score was composed by Ron Goodwin.

The plot centres on a serial killer in contemporary London. In a very early scene there is dialogue that mentions two actual London serial murder cases: the Christie murders in the early 1950s, and the Jack the Ripper murders in 1888. Barry Foster has said that the real life inspiration for his character was Neville Heath, an English serial killer who would often pass himself off as an officer in the RAF.[3]

Frenzy was the third film Hitchcock made in Britain after he moved to Hollywood in 1939. The other two were Under Capricorn in 1949 and Stage Fright in 1950 (although there were some interior and exterior scenes filmed in London for the 1956 remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much). The last film he made in Britain before his move to America was Jamaica Inn (1939). The film was screened at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival, but was not entered into the main competition.[4]

Plot

In London, a serial killer is raping women and strangling them with neckties. Most of the film takes place in Covent Garden, which at the time was still the wholesale fruit and vegetable market district. Fairly early in the film, the audience sees that fruit merchant Robert Rusk (Barry Foster) is in fact the murderer. However, circumstantial evidence has already built up around his friend Richard Blaney (Jon Finch).

Blaney's ex-wife, Brenda (Barbara Leigh-Hunt), runs a matchmaking service that Rusk used until he was blacklisted for beating up his dates. One day, Rusk shows up at her office and tries to seduce her; when she spurns his advances, he rapes and strangles her in a fit of rage. Suspicion falls on Blaney, who is previously seen threatening his ex-wife in public, as well as being seen leaving her building shortly after her murder. The subsequent murder of Blaney's girlfriend, Barbara "Babs" Milligan (Anna Massey), occurs off-screen: the audience sees her entering Rusk's apartment with him, but the camera then pulls back down the stairs all the way out to the other side of the street.

The audience next sees Rusk at night carrying a large sack and lifting it into the back of a lorry among sacks of unsold potatoes bound for Lincolnshire. Rusk soon finds that his distinctive jeweled tie pin (with the initial R) is missing, and realises that Babs must have torn it off as he was murdering her. He climbs into the back of the lorry, but it starts off on its journey north. The killer desperately scrabbles through the sack of potatoes to find the dead woman's hand. Rigor mortis has set in, and he has to break her fingers in order to prise the pin from her grasp.

Owing to fake evidence set up by Rusk, Blaney is gaoled while protesting his innocence. Chief Inspector Oxford (Alec McCowen), the detective investigating the murders, reconsiders the previous events and begins to believe that he has arrested the wrong man. He discusses the case with his wife (Vivien Merchant) in several scenes of comic relief concerning her pretensions as a gourmet cook.

With the help of his fellow inmates, Blaney escapes from prison. Oxford knows he will head to Rusk's flat for revenge, and immediately goes there. Blaney arrives first, to find that the door to the flat is unlocked. He creeps in and sees what appears to be Rusk asleep in bed, and strikes the body three times with a metal bar. However, the body is in fact the corpse of another of Rusk's female victims, strangled by a necktie.

Oxford bursts through the door. Blaney is still standing by the corpse holding the metal bar, and begins to protest his innocence, but then they both hear something or someone banging heavily coming up the staircase. The two men wait in the flat and witness Rusk dragging a large trunk inside to cart away the body, only to come face to face with two determined witnesses. The film ends with Oxford's urbane but pointed comment, "Mr. Rusk, you're not wearing your tie." Rusk drops the trunk in defeat.

Cast

|

|

Cast notes

- Alfred Hitchcock's cameo appearance can be seen (three minutes into the film) in the centre of a crowd scene, wearing a bowler hat. Teaser trailers show a Hitchcock-like dummy floating in the River Thames and Hitchcock introducing the audience to Covent Garden via the fourth wall.

- Michael Caine was Hitchcock's first choice for the role of Rusk, the main antagonist, but Caine thought the character was disgusting and said "I don't want to be associated with the part." Foster was cast after Hitchcock saw him in Twisted Nerve (which also featured Frenzy co-star Billie Whitelaw).

- Vanessa Redgrave reportedly turned down the role of Brenda, and Deep Red's David Hemmings (who had co-starred with Redgrave in Blow-Up) was considered to play Blaney.

- Helen Mirren, who later in life played a film version of Hitchcock's wife Alma Reville in Hitchcock, met with the director and eventually turned down the role of Babs Milligan, and years later regretted it.

Production

After a pair of unsuccessful films depicting political intrigue and espionage, Hitchcock returned to the murder genre with this film. The narrative makes use of the familiar Hitchcock theme of an innocent man overwhelmed by circumstantial evidence and wrongly assumed to be guilty. Some critics consider Frenzy the last great Hitchcock film and a return to form after his two previous works, Topaz and Torn Curtain.

Hitchcock set and filmed Frenzy in London after many years making films in the United States. The film opens with a sweeping shot along the Thames to Tower Bridge, and while the interior scenes were filmed at Pinewood Studios, much of the location filming was done in and around Covent Garden and was an homage to the London of Hitchcock's childhood. The son of a Covent Garden merchant, Hitchcock filmed several key scenes showing the area as the working produce market that it was. Aware that the area's days as a market were numbered, Hitchcock wanted to record the area as he remembered it. According to the making-of feature on the DVD, an elderly man who remembered Hitchcock's father as a dealer in the vegetable market came to visit the set during the filming and was treated to lunch by the director.

No. 31, Ennismore Gardens Mews, was used as the home of Brenda Margaret Blaney during the filming of Frenzy.[5]

During shooting for the film, Hitchcock's wife and longtime collaborator Alma had a stroke. As a result, some sequences were shot without Hitchcock on the set so he could tend to his wife.[6]

The film was the first Hitchcock film to have nudity. There are a number of classic Hitchcock set pieces in the film, particularly the long tracking shot down the stairs when Babs is murdered. The camera moves down the stairs, out the doorway (with a rather clever edit just after the camera exits the door which marks where the scene moves from the studio to the location footage) and across the street where the usual activity in the market district goes on with patrons unaware that a murder is occurring in the building. A second sequence set in the back of a delivery truck full of potatoes increases the suspense as the murderer Rusk attempts to retrieve his tie pin from the corpse of Babs. Rusk struggles with the hand and has to break the fingers of the corpse in order to retrieve his tie pin and try to escape unseen from the truck.[7]

The part of London shown in the film still exists more or less intact, but the fruit and vegetable market no longer operates from that site, having relocated in 1974. The buildings seen in the film are now occupied by banks and legal offices, restaurants and nightclubs, such as Henrietta Street, where Rusk lived (and Babs met her untimely demise). Oxford Street, which had the back alley (Dryden Chambers, now demolished) leading to Brenda Blaney's matrimonial agency, is the busiest shopping area in Britain. Nell of Old Drury, which is the public house where the doctor and solicitor had their frank, plot-assisting discussion on sex killers, is still a thriving bar. The lanes where merchants and workers once carried their produce, as seen in the film, are now occupied by tourists and street performers.

Novelist La Bern later expressed his dissatisfaction with Shaffer's adaptation of his book.[8]

Soundtrack

Henry Mancini was originally hired as the film's composer. His opening theme was written in Bachian organ andante, opening in D minor, for organ and an orchestra of strings and brass, and was intended to express the formality of the grey London landmarks, but Hitchcock thought it sounded too much like Bernard Herrmann's scores. According to Mancini, "Hitchcock came to the recording session, listened awhile and said 'Look, if I want Herrmann, I'd ask for Herrmann.'" After an enigmatic, behind-the-scenes melodrama, the composer was fired. He never understood the experience, insisting that his score sounded nothing like Herrmann. In those days, Mancini had full music measurements sheet and he had to pay all transportation and accommodations himself. In his autobiography, Mancini reports that the discussions between himself and Hitchcock seemed clear, he thought he understood what was wanted, but he was replaced and flew back home to Hollywood. The irony was that Mancini was now being second-guessed for being too dark and symphonic after having been criticized for being too light before. Mancini's experience with Frenzy was a painful topic for the composer for years to come.

Hitchcock then hired composer Ron Goodwin to write the score after being impressed with some of his earlier work. He had Goodwin rescore the opening titles in the style of a London travelogue - the director had heard his score for the Peter Sellers sketch, Balham, Gateway to the South.[9] Goodwin's music had a lighter tone in the opening scenes, and scenes featuring London scenery, while there were darker undertones in certain other scenes.

Reception

Frenzy ranked #33 on Variety's list of the 50 Top Grossing Films of 1972. The movie had total takings of $4,809,694 at the domestic box office (the United States and Canada), which is approximately $27,254,933 in today's funds.[10][11]

The film received positive reviews from critics. The film was the subject of the 2012 book Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece by Raymond Foery.[12] Frenzy currently holds an 87% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 31 reviews.[13]

Accolades

| Award | Category | Subject | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Motion Picture – Drama | Alfred Hitchcock | Nominated |

| Best Director | Nominated | ||

| Best Screenplay | Anthony Shaffer | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | Ron Goodwin | Nominated | |

References

- ↑ Nat Segaloff, Final Cuts: The Last Films of 50 Great Directors, Bear Manor Media 2013 p 131

- ↑ "Frenzy, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ↑ http://www.dvdtalk.com/reviews/56856/alfred-hitchcock-the-masterpiece-collection-limited-edition/

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: Frenzy". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- ↑ Mews News. Issue 32. Lurot Brand. Published winter 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ McGilligan, Patrick (30 September 2003). Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. Regan Books.

- ↑ Wood, Robin "Hitchcock's Films Revisited" Columbia University Press, 2002

- ↑ "Letters to the Editor: Hitchcock's "Frenzy", The Times, 29 May 1972". Hitchcockwiki.com. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/news/2003/jan/11/guardianobituaries.artsobituaries

- ↑ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Community Development Project. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ↑ Foery, Raymond (2012). Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7756-6.

- ↑ Foery, Raymond (2012). Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7756-6.

- ↑ https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/frenzy/?search=Frenzy

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Frenzy |

- Frenzy at the Internet Movie Database

- Frenzy at AllMovie

- Frenzy at Rotten Tomatoes

- Frenzy at Dial H for Hitchcock