French architecture

French architecture ranks high among France's many accomplishments. Indications of the special importance of architecture in France were the founding of the Academy of Architecture in 1671, the first such institution anywhere in Europe, and the establishment in 1720 of the Prix de Rome in architecture, a competition of national interest, funded by the state, and an honor intensely pursued.

History

Gallo-Roman

The architecture of Ancient Rome at first adopted the external Greek architecture and by the late Republic, the architectural style developed its own highly distinctive style by introducing the previously little-used arches, vaults and domes. A crucial factor in this development, coined the Roman Architectural Revolution, was the invention of concrete. Social elements such as wealth and high population densities in cities forced the ancient Romans to discover new (architectural) solutions of their own. The use of vaults and arches together with a sound knowledge of building materials, for example, enabled them to achieve unprecedented successes in the construction of imposing structures for public use.

Notable examples in France during the period are Alyscamps in Arles and Maison Carrée in Nîmes. The Alyscamps is a large Roman necropolis, which is a short distance outside the walls of the old town of Arles. It was one of the most famous necropolises of the ancient world. The name is a corruption of the Latin Elisii Campi (that is, Champs-Élysées or Elysian Fields). They were famous in the Middle Ages and are referred to by Ariosto in Orlando Furioso and by Dante in the Inferno.[1] The Alyscamps continued to be used well into medieval times, although the removal of Saint Trophimus' relics to the cathedral in 1152 reduced its prestige.

Pre-Romanesque

The unification of the Frankish kingdom under Clovis I (465–511) and his successors, corresponded with the need for the building of churches, and especially monastery churches, as these were now the power-houses of the Merovingian church. Plans often continued the Roman basilica tradition, but also took influences from as far away as Syria and Armenia. In the East, most structures were in timber, but stone was more common for significant buildings in the West and in the southern areas that later fell under Merovingian rule. Most major churches have been rebuilt, usually more than once, but many Merovingian plans have been reconstructed from archaeology. The description in Bishop Gregory of Tours' History of the Franks of the basilica of Saint-Martin, built at Tours by Saint Perpetuus (bishop 460-490) at the beginning of the period and at the time on the edge of Frankish territory, gives cause to regret the disappearance of this building, one of the most beautiful Merovingian churches, which he says had 120 marble columns, towers at the East end, and several mosaics: "Saint-Martin displayed the vertical emphasis, and the combination of block-units forming a complex internal space and the correspondingly rich external silhouette, which were to be the hallmarks of the Romanesque".[2] A feature of the basilica of Saint-Martin that became a hallmark of Frankish church architecture was the sarcophagus or reliquary of the saint raised to be visible and sited axially behind the altar, sometimes in the apse. There are no Roman precedents for this Frankish innovation.[3] A number of other buildings, now lost, including the Merovingian foundations of Saint-Denis, St. Gereon in Cologne, and the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris, are described as similarly ornate.

Romanesque

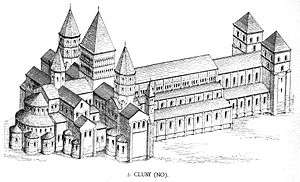

Architecture of a Romanesque style developed simultaneously in parts of France in the 10th century and prior to the later influence of the Abbey of Cluny. The style, sometimes called "First Romanesque" or "Lombard Romanesque", is characterised by thick walls, lack of sculpture and the presence of rhythmic ornamental arches known as a Lombard band. The Angoulême Cathedral is one of several instances in which the Byzantine churches of Constantinople seem to have been influential in the design in which the main spaces are roofed by domes. This structure has necessitated the use of very thick walls, and massive piers from which the domes spring. There are radiating chapels around the apse, which is a typically French feature and was to evolve into the chevette. Notre-Dame in Domfront, Normandy is a cruciform church with a short apsidal east end. The nave has lost its aisle, and has probably some of its length. The crossing has a tower that rises in two differentiated stages and is surmounted by a pyramidical spire of a type seen widely in France and Germany and also on Norman towers in England. The Abbey of Fongombault in France shows the influence of the Abbey of Cluny. The cruciform plan is clearly visible. There is a chevette of chapels surrounding the chance apse. The crossing is surmounted by a tower. The transepts end with gables.

The Saint-Étienne located in Caen presents one of the best known Romanesque facades of Northern France, with three portals leading into the nave and aisles, and a simple arrangement of identical windows between the buttresses of the tall towers. Begun in the 1060s, it was a prototype for Gothic facades. The spires and the pinnacles, which appear to rise inevitably from the towers, are of the early 13th century. The Trinité Church of Caen has a greater emphasis on the central portal and the arrangement of the windows above it. The decoration of the towers begins at a lower level to that at Saint-Étienne, giving them weight and distinction. The upper balustrades are additions in the Classical style. The facade of Le Puy-en-Velay in Haute-Loire has a complex arrangement of openings and blind arcades that was to become a feature of French Gothic facades. It is made even richer by the polychrome brick used in diverse patterns, including checkerboard, also a feature of ceramic decoration of Spanish churches of this period. The profile of the aisles is screened by open arches, perhaps for bells. Angoulême Cathedral is another richly decorated facade, but here it is of dressed stone with sculpture as the main ornament. The manner of arrangement of the various arches is not unlike that at Le Puy-en-Velay, but forming five strong vertical divisions which suggests that the nave is framed by two aisles on each side. In fact, the church has no aisles and is roofed by domes. The figurative sculpture, in common with much Romanesque sculpture, is not closely integrated to the arched spaces into which it has been set.

At Autun Cathedral, the pattern of the nave bays and aisles extends beyond the crossing and into the chancel, each aisle terminating in an apse. Each nave bay is separated at the vault by a transverse rib. Each transept projects to the width of two nave bays. The entrance has a narthex which screens the main portal. This type of entrance was to be elaborated in the Gothic period on the transepts at Chartres.

Medieval

French Gothic architecture is a style of architecture prevalent in France from 1140 until about 1500, which largely divided into four styles, Early Gothic, High Gothic, Rayonnant, Late Gothic or Flamboyant style. The Early Gothic style began in 1140 and was characterized by the adoption of the pointed arch and transition from late Romanesque architecture. To heighten the wall, builders divided it into four tiers: arcade (arches and piers), gallery, triforium, and clerestorey. To support the higher wall builders invented the flying buttresses, which reached maturity only at High Gothic during the 13th century. The vaults were six ribbed Sexpartite vaults. Notable structures of the style include the East end of the Abbey Church of St Denis, Sens Cathedral, Notre-Dame of Laon, the West facade of Chartres Cathedral, Notre Dame de Paris, Lyon Cathedral and Toul Cathedral.

The High Gothic style of the 13th century canonized proportions and shapes from early Gothic and developed them further to achieve light, yet tall and majestic structures. The wall structure was modified from four to only three tiers: arcade, triforium, and clerestorey. Piers coronations were smaller to avoid stopping the visual upward thrust. The clerestorey windows changed from one window in each segment, holed in the wall, to two windows united by a small rose window. The rib vault changed from six to four ribs. The flying buttresses matureed, and after they were embraced at Notre-Dame de Paris and Notre-Dame de Chartres, they became the canonical way to support high walls, as they served both structural and ornamental purposes. The main body of Chartres Cathedral (1194–1260), Amiens Cathedral, and Bourges Cathedral are also representatives of the style.

Aside from these Gothic styles, there is another style called "Gothique Méridional" (or Southern Gothic, opposed to Gothique Septentrional or Northern Gothic). This style is characterised by a large nave and has no transept. Examples of this Gothic architecture would be Notre-Dame-de-Lamouguier in Narbonne and Sainte-Marie in Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges.

Renaissance

During the early years of the 16th century the French were involved in wars in northern Italy, bringing back to France not just the Renaissance art treasures as their war booty, but also stylistic ideas. In the Loire Valley a wave of building was carried and many Renaissance chateaux appeared at this time, the earliest example being the Château d'Amboise (c. 1495) in which Leonardo da Vinci spent his last years. The style became dominant under Francis I (See Châteaux of the Loire Valley).

The style progressively developed into a French Mannerism known as the Henry II style under architects such as Sebastiano Serlio, who was engaged after 1540 in work at the Château de Fontainebleau. At Fontainebleau Italian artists such as Rosso Fiorentino, Francesco Primaticcio, and Niccolo dell' Abbate formed the First School of Fontainebleau. Architects such as Philibert Delorme, Androuet du Cerceau, Giacomo Vignola, and Pierre Lescot, were inspired by the new ideas. The southwest interior facade of the Cour Carree of the Louvre in Paris was designed by Lescot and covered with exterior carvings by Jean Goujon. Architecture continued to thrive in the reigns of Henry II and Henry III.

Baroque

French Baroque is a form of Baroque architecture that evolved in France during the reigns of Louis XIII (1610–43), Louis XIV (1643–1714) and Louis XV (1714–74). French Baroque profoundly influenced 18th-century secular architecture throughout Europe. Although the open three wing layout of the palace was established in France as the canonical solution as early as the 16th century, it was the Palais du Luxembourg (1615–20) by Salomon de Brosse that determined the sober and classicizing direction that French Baroque architecture was to take. For the first time, the corps de logis was emphasized as the representative main part of the building, while the side wings were treated as hierarchically inferior and appropriately scaled down. The medieval tower has been completely replaced by the central projection in the shape of a monumental three-storey gateway.

Probably the most accomplished formulator of the new manner was François Mansart, credited with introducing the full Baroque to France. In his design for Château de Maisons (1642), Mansart succeeded in reconciling academic and baroque approaches, while demonstrating respect for the gothic-inherited idiosyncrasies of the French tradition. Maisons-Laffitte illustrates the ongoing transition from the post-medieval chateaux of the 16th century to the villa-like country houses of the eighteenth. The structure is strictly symmetrical, with an order applied to each story, mostly in pilaster form. The frontispiece, crowned with a separate aggrandized roof, is infused with remarkable plasticity and the whole ensemble reads like a three-dimensional whole. Mansart's structures are stripped of overblown decorative effects, so typical of contemporary Rome. Italian Baroque influence is muted and relegated to the field of decorative ornamentation.

The next step in the development of European residential architecture involved the integration of the gardens in the composition of the palace, as is exemplified by Vaux-le-Vicomte (1656–61), where the architect Louis Le Vau, the designer Charles Le Brun and the gardener André Le Nôtre complemented each other. From the main cornice to a low plinth, the miniature palace is clothed in the so-called "colossal order", which makes the structure look more impressive. The creative collaboration of Le Vau and Le Nôtre marked the arrival of the "Magnificent Manner" which allowed to extend Baroque architecture outside the palace walls and transform the surrounding landscape into an immaculate mosaic of expansive vistas.

Rococo

Rococo developed first in the decorative arts and interior design. Louis XIV's succession brought a change in the court artists and general artistic fashion. By the end of the old king's reign, rich Baroque designs were giving way to lighter elements with more curves and natural patterns. These elements are obvious in the architectural designs of Nicolas Pineau. During the Régence, court life moved away from Versailles and this artistic change became well established, first in the royal palace and then throughout French high society. The delicacy and playfulness of Rococo designs is often seen as perfectly in tune with the excesses of Louis XV's regime.

The 1730s represented the height of Rococo development in France. Rococo still maintained the Baroque taste for complex forms and intricate patterns, but by this point, it had begun to integrate a variety of diverse characteristics, including a taste for Oriental designs and asymmetric compositions. The style had spread beyond architecture and furniture to painting and sculpture. The Rococo style spread with French artists and engraved publications. It was readily received in the Catholic parts of Germany, Bohemia, and Austria, where it was merged with the lively German Baroque traditions.

Neoclassicism

The first phase of neoclassicism in France is expressed in the "Louis XVI style" of architects like Ange-Jacques Gabriel (Petit Trianon, 1762–68); the second phase, in the styles called Directoire and "Empire", might be characterized by Jean Chalgrin's severe astylar Arc de Triomphe (designed in 1806). In England the two phases might be characterized first by the structures of Robert Adam, the second by those of Sir John Soane. The interior style in France was initially a Parisian style, the "Goût grec" ("Greek style") not a court style. Only when the young king acceded to the throne in 1771 did Marie Antoinette, his fashion-loving Queen, bring the "Louis XVI" style to court.

From about 1800 a fresh influx of Greek architectural examples, seen through the medium of etchings and engravings, gave a new impetus to neoclassicism that is called the Greek Revival. Neoclassicism continued to be a major force in academic art through the 19th century and beyond— a constant antithesis to Romanticism or Gothic revivals— although from the late 19th century on it had often been considered anti-modern, or even reactionary, in influential critical circles. By the mid-19th century, several European cities - notably St Petersburg, Athens, Berlin and Munich - were transformed into veritable museums of Neoclassical architecture. By comparison, the Greek revival in France was never popular with either the State or the public. What little there is started with Charles de Wailly's crypt in the church of St Leu-St Gilles (1773–80), and Claude Nicolas Ledoux's Barriere des Bonshommes (1785-9). First-hand evidence of Greek architecture was of very little importance to the French, due to the influence of Marc-Antoine Laugier's doctrines that sought to discern the principles of the Greeks instead of their mere practices. It would take until Laboustre's Neo-Grec of the second Empire for the Greek revival to flower briefly in France.

Differences Between Homes in the 18th Century and 19th Century

The difference between 1800 to 1900 is enormous. In 1800 all poor people, rural and urban, lived in one room homes. In the country that room might be divided in two by a low wall that kept the domestic animals in. Peasants were terrified that wolves would devour their cow and goat or that the neighbors would steal them. Sometimes there was a loft, if you were a bit more prosperous. People had fireplaces, but not stoves, for a lot of people couldn't afford them. Glass had gotten much cheaper but windows were still sealed with oiled parchment to let in some sunlight and keep out rain. Some houses had wooden floors, many didn't (packed earth instead). There was no running water. Peasants couldn't afford a tub, and they didn't all live near rivers, so bathing was rare. Even where there was a river or pond, people were scared to death of water spirits that would drown them. The brightest lads could get educated by the local cathedral, if the parents let him. Although rents were low, food was very dear. Masonry was skilled work, generating good wages and steady work. A lot of the income from the average French citizen went to bread. In the cities 2 or more families might share a single room, again with no running water and no privacy. By 1900 homes, even poor ones, had wooden floors, perhaps 2-3 rooms, a shingled roof (thatched straw was still in use but it was a fire hazard), real glass windows, and a shed or barn for domestic animals. Some homes had running water, but not a toilet or tub. Just as in the rural South outhouses were in use well into the 20th century. Homes now would have wallpaper and curtains, a real table instead of boards laid across trestles, real chairs instead of stumps, a foot powered sewing machine, kerosene lamps, closets and more.[4]

Second Empire

During the mid-19th century when Napoleon III established the Second Empire, Paris became a glamorous city of tall, imposing buildings. Many homes were embellished with details such as paired columns and elaborate wrought iron cresting appeared along rooftops. But the most striking feature borrowed from this period is the steep, boxy mansard roof. You can recognize a mansard roof by its trapezoid shape. Unlike a triangular gable, a mansard roof has almost no slope until the very top, when it abruptly flattens. This nearly perpendicular roofline creates a sense of majesty, and also allows more usable living space in the attic. In the United States, Second Empire is a Victorian style. However, you can also find the practical and the decidedly French mansard roof on many contemporary homes.

Beaux Arts

Another Parisian style, Beaux-Arts originated from the legendary École des Beaux Arts (School of Fine Arts). Flourishing during the 19th and early 20th centuries, it was a grandiose elaboration on the more refined neoclassical style. Symmetrical façades were ornamented with lavish details such as swags, medallions, flowers, and shields. These massive, imposing homes were almost always constructed of stone and were reserved for only the very wealthy. However a more 'humble' home might show Beaux Arts influences if it has stone balconies and masonry ornaments. Many American architects studied at the École des Beaux Arts, and the style strongly influenced United States architecture from about 1880 to 1920.

Art Nouveau & Art Deco

Modernist and Contemporary

- Main: Modernist architecture in France

Some renowned modernist and contemporary French designers and architects include:

- Le Corbusier

- Robert Mallet-Stevens

- Frédéric Borel,

- Dominique Perrault,

- Christian de Portzamparc

- Jean Nouvel

- List of Post World War II French architects

- Examples of modernist and contemporary buildings in France

- Villa Savoye

- Notre Dame du Haut - "Chapel du Ronchamp"

- Le Corbusier buildings

- Villa Noailles

- Institut du Monde Arabe

- Jean Nouvel buildings

Regional architecture

French style can vary from being very modern to rustic and antique in appearance.

Provincial

One of the most distinctive characteristics of many French buildings is the tall second story windows, often arched at the top, that break through the cornice and rise above the eaves. This unusual window design is especially noticeable on America's French provincial homes. Modeled after country manors in the French provinces, these brick or stucco homes are stately and formal. They have steep hipped roofs and a square, symmetrical shape with windows balanced on each side of the entrance. The tall second story windows add to the sense of height.

Normandy

In Normandy and the Loire Valley of France, farm silos were often attached to the main living quarters instead of a separate barn. After World War I, Americans romanticized the traditional French farmhouse, creating a style known as French Normandy. Sided with stone, stucco, or brick, these homes may suggest the Tudor style with decorative half timbering (vertical, horizontal, and diagonal strips of wood set in masonry). The French Normandy style is distinguished by a round stone tower topped by a cone-shaped roof. The tower is usually placed near the centre, serving as the entrance to the home. French Normandy and French provincial details are often combined to create a style simply called French Country or French Rural carved or embossed on mouldings, sconces, and banisters.

Overseas architecture

America

French Creole architecture is an American Colonial style that developed in the early 18th century in the Mississippi Valley, especially in Louisiana. French Creole buildings borrow traditions from France, the Caribbean, and many other parts of the world such as Spanish, African, Native American, and other heritages. French Creole homes from the Colonial period were especially designed for the hot, wet climate of that region. Traditional French Creole homes had some or all of these features:

- Timber frame with brick or "Bousillage" (mud combined with moss and animal hair)

- Wide hipped roof extends over porches

- Thin wooden columns

- Living quarters raised above ground level

- Wide porches, called "galleries"

- No interior hallways

- Porches used as passageway between rooms

- French doors (doors with many small panes of glass)

See also

- Art Deco

- Art Nouveau

- Châteauesque

- Enclos paroissial

- Fountains in France

- French architecture index

- French Colonial Architecture

- French landscape garden

- Jardin à la française

- Gardens in France index

- Gardens of the French Renaissance

- List of French architects

- Modernisme

- Architecture of Paris

- Paris architecture of the Belle Époque

- Remarkable Gardens of France

References

- Notes

- ↑ Lawrence Durrell, Caesar's Vast Ghost,Faber and Faber, 1990; paperback with corrections 1995; ISBN 0-571-21427-4; see page 98 in the reset edition of 2002

- ↑ V.I. Atroshenko and Judith Collins, The Origins of the Romanesque (Lund Humphries, London) 1986, p. 48. ISBN 0-85331-487-X

- ↑ Werner Jacobsen, "Saints' Tombs in Frankish Church Architecture" Speculum 72.4 (October 1997:1107-1143).

- ↑ "France's growing poor: Where do they live?". 2014-01-28. Retrieved 2016-10-30.

- Sources

- Kalnein, Wend von (1995). Architecture in France in the Eighteenth Century. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300060133.

External links

Media related to Architecture of France at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Architecture of France at Wikimedia Commons