Forerunner (magazine)

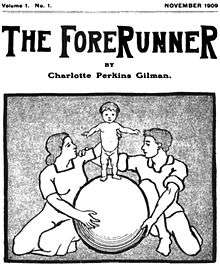

The Forerunner was a monthly magazine produced by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (best known as the writer of The Yellow Wallpaper), from 1909 through 1916. During that time, she wrote all of every issue—editorials, critical articles, book reviews, essays, poems, stories, and six serialized novels. The magazine was based in New York City.[1]

History and profile

The first issue of the Forerunner appeared in November 1909.[2] Among the most interesting pieces published in The Forerunner are the three novels of Gilman's feminist utopian trilogy, Moving the Mountain (1911), Herland (1915), and With Her in Ourland (1916). Herland, the most famous of these books, presents an all-women society in which women reproduce themselves through parthenogenesis, and the female value of nurturing is upheld by the community.

Gilman used The Forerunner as the venue for other major works, including Man-Made World (1911) and her novels What Diantha Did (1909–10), The Crux (1911), Mag-Marjorie (1912), Won Over (1913), and Begnina Machiavelli (1914). The magazine ceased publication in 1916.[2]

The Forerunner takes up 28 full-length books.

Philosophy

As an advocate for women’s rights, Gilman began publishing Forerunner to reach out to women during the early 1900s who hoped to further their franchise and natural rights to become equal to the rights which were afforded to men. She aimed to change the idea that women must be passive and their only role be in household duties. Gilman wanted to attract the average woman to become a reader, and aid in persuading them to fight for a just change in society. According to Cane and Alves, “The short fiction written and published by Charlotte Perkins Gilman in her magazine, the Forerunner (1909–16), concerns ordinary women who deflect the traditional trajectories of their lives to create better situations for themselves and, in so doing, improve the lives of those around them.”[3] Forerunner not only fought to contradict the popular media of the time, but also proposed new ideas on the place of women in society.

The writings published by Gilman in Forerunner were of sharp contrast to the texts that were available to women during the early 1900s. Women were expected to read about the appropriate etiquette assumed for them in marriage and the household. For example, the paramount journal of the early 1900s was Ladies’ Home Journal, which portrayed women as passive, focused on marriage and family issues, and was concerned with reaching the specific audience of middle class white women.[4] Cane and Alves bring to light Gilman’s goals. “Gilman’s Forerunner, on the other hand, existed to counteract popular images of women and such personal limitations on their everyday lives that the mass media promulgated.”[5] Fighting the assumed roles of women and the representation of women in society was not a simple undertaking given the constraints placed upon women by the general public and prevailing cultural standards. A patriarchal society was rampantly dominant throughout the standing government and general population. The beliefs held by the community of a woman’s place restricted a woman’s access to opportunity and education, a problem which Gilman was passionately determined to change.

As Gilman herself describes, “The forerunner ... does not fill your brain with more facts, but stirs it to new action...It stands for Human Progress, and concentrates upon the Progress of Women only because their present position is the world’s stumbling block.”[6] By publishing the Forerunner, Gilman hoped to inspire woman to take the steps towards changing the concepts of what a woman “should be” and stimulate the community to promote a commonality in the civil liberties of women. By perpetuating a diverse collection of ideas in her writings, Gilman wrote to address and effect the main issue she believed was adversely impacting the nation.

Gilman believed, one of the main issues faced in the society of the time period was a lack of opportunities and education, beyond motherly knowledge, afforded to women even though these opportunities were readily available to bolster the advancement of men. She discusses this matter of contention in her writing Our Brains and What Ails Them, published in Forerunner in 1912. Her stance that women are stunted in society is expressed in this article. She writes, “So the human brain has grown, by normal use and exercise, in the male; and been stunted, denied normal use and exercise in the female...”[7] She supported the idea that, “The major lack in the minds of women is in experience.”[8] Hoping to break new ground in the forefront of the women’s movement, Forerunner confronts the lack of education for women head on.

The solutions offered for the problems Gilman believed faced women were not ones of rebellion and fast-paced revolution, but realistic subtle changes which would not intimidate the reader. Gilman argued that, “The liberation of women- and of children and men, for that matter- required getting women out of the house, both practically and ideologically.” [9] The articles were mainly stories of fiction which were more relatable to her audience at the time, and useful in contrasting the writings in other popular media outlets. “Gilman took a conservative, slow-going approach to social change for two main reasons: First, she adhered to the notion that social change was based on the scientific evidence of evolution and she understood the evolutionary process to be gradual; second, as an observer of the suffrage campaigns undertaken within her lifetime, she had learned that the less radical approaches were the ones that won adherents, while more revolutionary schemes frightened and alienated many middle- class women.”[10] Gilman succeeded in commanding 1300 subscribers at the peak of the magazine’s circulation, equalling around 6500 readers. The magazine was unbacked by advertisers and paid for by Gilman herself.[11] It was published once a month, costing a dollar per year.

Gilman’s drive for social change was the inspiration for Forerunner, and its controversial articles. She succeeded in administering progressive ideas for change to the magazine’s readers, growing support for her desires during the women’s suffrage movement.

Background

Charlotte Perkins Gilman states in her magazine The Forerunner, “Then This: It strives in prose and verse, Thought, fancy, fact and fun, To tell the things we ought to know, To point the way we ought to go, So audibly to bless and curse, That he who reads may run.” This excerpt reveals the background and reasons why Gilman started her magazine The Forerunner. Gilman grew up during the time of the Industrial Revolution, the Women’s Movement and the development of the major schools of social sciences. This provided her with an understanding of the effect these certain events had on the development of the American society we live in today. Gilman’s parents had conflicting world views, which is where her passion to reach out began. Gilman’s mother, Mary A. Fitch and her family were very conservative while her father, Fredrick Beecher Perkins and his family were known for their radical reformist family member, Isabella Beecher Stowe, who was a famous suffragist and Harriet Beecher Stowe who was an abolitionist. Due to this Fredrick left his family and only had occasional support for them in further situations. Gilman was blessed with a great gift in writing and used it to shed light on these problems she experienced growing up well as the problem of women’s right and the status of women during this time (1860-1935). She does a great job of providing this world with understanding and helping change the worlds view on women’s rights and statuses.[12][13]

References

- ↑ "The Forerunner:". Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- 1 2 "The Forerunner archives". UPenn Libraries. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ↑ Cane, Aleta; Susan, Alves (2005). The Only Efficient Instrument:Women & The Periodical. University of Iowa Press. p. 95. ISBN 9781587294006.

- ↑ Cane, Aleta; Susan, Alves (2005). The Only Efficient Instrument:Women & The Periodical. University of Iowa Press. p. 95. ISBN 9781587294006.

- ↑ Cane, Aleta; Susan, Alves (2005). The Only Efficient Instrument:Women & The Periodical. University of Iowa Press. p. 95. ISBN 9781587294006.

- ↑ Gilman, Charlotte (February 1914). The Forerunner: A Monthly Magazine (Volume 5, Issue 2 ed.). Charltone CO., 67 Wall St., New York City: Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

- ↑ Harris, Leonard; Pratt, Scott; Waters, Anne (2002). American Philosophies: An Anthology. Blackwell Publishers Inc. p. 131.

- ↑ Harris, Leonard; Pratt, Scott; Waters, Anne (2002). American Philosophies: An Anthology. Blackwell Publishers Inc. p. 132.

- ↑ Gilman, Charlotte (2005). Human Work. AltaMira Press. p. xiv. ISBN 0-7591-0904-4.

- ↑ Cane, Aleta; Susan, Alves (2005). The Only Efficient Instrument:Women & The Periodical. University of Iowa Press. p. 96,97. ISBN 9781587294006.

- ↑ Gilman, Charlotte (February 1914). The Forerunner: A Monthly Magazine (Volume 5, Issue 2 ed.). Charltone CO., 67 Wall St., New York City: Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

- ↑ Gutenberg

- ↑ Gilman