Ford's Theatre

| |

| Address |

511 10th St, NW Washington, D.C. United States |

|---|---|

| Owner | National Park Service |

| Operator | Ford's Theatre Society |

| Type | Regional theatre |

| Capacity | 665 |

| Construction | |

| Opened | August 1863 |

| Reopened | 1968, 2009 |

| Website | |

|

Ford's Theatre National Historic Site | |

| |

| Coordinates | 38°53′48″N 77°1′33″W / 38.89667°N 77.02583°WCoordinates: 38°53′48″N 77°1′33″W / 38.89667°N 77.02583°W |

| Area | 0.29 acres (0.12 ha) (Theatre alone) less than one acre (entire NHS) |

| Built | 1863 |

| Architectural style | Late Victorian |

| Visitation | 856,079 (2005) |

| NRHP Reference # | 66000034[1] |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 2013 |

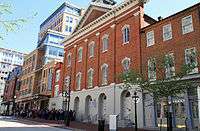

Ford's Theatre is a historic theatre in Washington, D.C., used for various stage performances beginning in the 1860s. It is also the site of the assassination of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865. After being shot, the mortally wounded president was carried across the street to the Petersen House, where he died the next morning.

The theatre was later used as a warehouse and office building, and in 1893 part of it collapsed, causing 22 deaths. It was renovated and re-opened as a theatre in 1968. During the 2000s, it was renovated again, opening on February 12, 2009, in commemoration of the bicentennial of Lincoln's birth. A related Center for Education and Leadership museum experience opened February 12, 2012 next to Petersen House.

The Petersen House and the theatre are preserved together as Ford's Theatre National Historic Site, administered by the National Park Service; programming within the theatre and the Center for Education is overseen separately by the Ford's Theatre Society in a public-private partnership.[2] Ford's Theatre is located at 511 10th Street, NW.

History

The site was originally a house of worship, constructed in 1833 as the second meeting house of the First Baptist Church of Washington, with Obadiah Bruen Brown as the pastor. In 1861, after the congregation moved to a newly built structure, John T. Ford bought the former church and renovated it into a theatre. He first called it Ford's Athenaeum. It was destroyed by fire in 1862, and was rebuilt the following year. When the new Ford's Theatre opened in August 1863, it had seating for 2,400 persons and was called a "magnificent new thespian temple".[3]

Just five days after General Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House, Lincoln and his wife attended a performance of Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre. The famous actor John Wilkes Booth, desperate to aid the dying Confederacy, stepped into the box where the presidential party was sitting and shot Lincoln. Booth then jumped onto the stage, and cried out "Sic semper tyrannis" (some heard "The South is avenged!") just before escaping through the back of the theatre.[4][5][6]

Following the assassination, the United States Government appropriated the theatre, with Congress paying Ford $88,000 in compensation,[7] and an order was issued forever prohibiting its use as a place of public amusement. Between 1866 and 1887, the theatre was taken over by the U.S. military and served as a facility for the War Department with records kept on the first floor, the Library of the Surgeon General's Office on the second floor, and the Army Medical Museum on the third. In 1887, the building exclusively became a clerk's office for the War Department, when the medical departments moved out.

On June 9, 1893, the front part of the building collapsed, killing 22 clerks and injuring another 68. This led some people to believe that the former church turned theatre and storeroom was cursed. The building was repaired and used as a government warehouse until 1911.

It languished unused until 1918. In 1928,[8] the building was turned over from the War Department Office to the Office of Public Buildings and Parks of the National Capital. A Lincoln museum opened on the first floor of the theatre building on February 12, 1932—Lincoln's 123rd birthday.[9] In 1933, the building was transferred to the National Park Service.

The restoration of Ford's Theatre was brought about by the two decade-long lobbying efforts of Democratic National Committeeman Melvin D. Hildreth and Republican North Dakota Representative Milton Young. Hildreth first suggested to Young the need for its restoration in 1945. Through extensive lobbying of Congress, a bill was passed in 1955 to prepare an engineering study for the reconstruction of the building.[10] In 1964 Congress approved funds for its restoration, which began that year and was completed in 1968.

On January 21,1968 Vice President Hubert Humphrey and 500 others dedicated the restored theater.[11] The theatre reopened on January 30, 1968, with a gala performance.[12]

The theatre was again renovated during the 2000s. It has a current seating capacity of 665.[13] The re-opening ceremony was on February 11, 2009,[14] which commemorated Lincoln's 200th birthday. The event featured remarks from President Barack Obama as well as appearances by Katie Couric, Kelsey Grammer, James Earl Jones, Ben Vereen, Jeffrey Wright, the President's Own Marine Band, Joshua Bell, Patrick Lundy and the Ministers of Music, Audra McDonald and Jessye Norman.[15]

Ford's Theatre National Historic Site

The National Historic Site consisting of two contributing buildings, the theatre and the Petersen House, was designated in 1932.

The Ford's Theatre Museum beneath the theatre contains portions of the Olroyd Collection of Lincolniana. Most recently renovated and reimagined for a July 2009 reopening,[16] the Museum is run through a partnership with the National Park Service and the private non-profit 501(c)(3) Ford's Theatre Society. The collection includes multiple items related to the assassination, including the Derringer pistol used to carry out the shooting, Booth's diary and the original door to Lincoln's theatre box. In addition, a number of Lincoln's family items, his coat (without the blood-stained pieces), some statues of Lincoln and several large portraits of the President are on display in the museum. The blood-stained pillow from the President's deathbed is in the Ford's Theatre Museum. In addition to covering the assassination conspiracy, the renovated museum focuses on Lincoln's arrival in Washington, his presidential cabinet, family life in the White House and his role as orator and emancipator.[17] The museum also features exhibits about Civil War milestones and generals and about the building's history as a theatrical venue. The rocking chair in which Lincoln was sitting is now on display at The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

Tours of Ford's Theatre and the adjacent Petersen House are by timed-entry ticket. Tickets can be reserved ahead, and there are also tickets available on the day of entry on a first-come, first-served basis. Admission is free.

- Upper row of seats at Ford's Theatre.

View from beneath the balcony.

View from beneath the balcony.- The Presidential Box today.

Petersen House

Attendants, including Dr. Charles Leale, carried the President onto 10th Street. The doctor decided to take him to Petersen's boarding house across the street. The streets were extremely crowded with people because of the uproar. A captain cleared the way to the brick federal style rowhouse. A boarder, Henry Safford, noticed what was going on and stood on the front steps crying, "Bring him in here! Bring him in here!" Then he was taken into the bedroom in the rear of the parlors and placed on a bed that was not long enough for him. Mrs. Lincoln was escorted across the street by Clara Harris, who had been in the box during the shooting, and whose fiancé, Henry Rathbone, had been stabbed by Booth during the assassination. Rathbone, bleeding severely from the knife wound in his arm, collapsed from loss of blood after arriving at the Petersen House.

During the night and early morning, military guards patrolled outside to prevent onlookers from coming inside the house. A parade of government officials and physicians was allowed to come inside and pay respects to the unconscious President. Physicians continually removed blood clots which formed over the wound and poured out the excess brain fluid and brain matter from where the bullet had entered Lincoln's head in order to relieve pressure on the brain. However, the external and internal hemorrhaging continued throughout the night. Lincoln died in the house on April 15, 1865, at 7:22 a.m., at age 56. Among the attending physicians was Anderson Ruffin Abbott, a black, Canadian-educated doctor who later wrote "Some recollections of Lincoln's assassination".[18]

The National Park Service has operated the Petersen House as a historic house museum since 1933. The rooms have been furnished to appear as if it were the night of Abraham Lincoln's death.[19]

In literature

Ford's Theatre is a key site in the children's historical novel Assassin by Anna Myers.

See also

- Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site

- Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

- Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial

- Lincoln Home National Historic Site

- Lincoln Memorial

- Lincoln Tomb

- Mount Rushmore

- Theater in Washington, D.C.

- United States Presidential Memorial

- President Lincoln's Cottage

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ http://fords.org/home/about-fords

- ↑ Samples, Gordon (1982). Lust for Fame: The Stage Career of John Wilkes Booth. Jefferson, N. Carolina: McFarland. p. 123. ISBN 0-89950-042-0.

- ↑ Donald, David Herbert (1995). Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80846-3.

- ↑ Smith, Gene (1992). American Gothic: the story of America's legendary theatrical family, Junius, Edwin, and John Wilkes Booth. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 154. ISBN 0-671-76713-5.

- ↑ Goodrich, Thomas (2005). The Darkest Dawn. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University. p. 97. ISBN 0-253-32599-4.

- ↑ Anderson, Brian (2014). Images of America: Ford's Theatre. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4671-2112-5

- ↑ Anderson, Brian (2014). Images of America: Ford's Theatre. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-4671-2112-5

- ↑ Anderson, Brian (2014). Images of America: Ford's Theatre. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4671-2112-5

- ↑ Eva Reffell, Ford's Theatre's Reconstruction: Warehouse, Museum, Pilgrimage Site (1865–1968), http://www.si.umich.edu/~rfrost/courses/ArchivesSem/papers/EvaReffell.pdf.

- ↑ The Times News, Henderson, NC https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1665&dat=19680122&id=VFRPAAAAIBAJ&sjid=ViQEAAAAIBAJ&pg=3896,1364150&hl=en

- ↑ Theodore Mann, Journeys in the Night: Creating a New American Theatre with Circle in the Square (NY: Applause Theatre and Cinema Books, 2007), 234-5

- ↑ Select Traveler Magazine: "Restored Theaters: Stage presence" May 13, 2010. http://selecttraveler.com/articles/restored-theaters-stage-presence

- ↑ United Press International "Ford's Theater Reopening" February 11, 2009.

- ↑ The Washington Post "At Historic Ford's Theatre, an Evening of Tributes to Lincoln's Legacy" February 12, 2009. BY PETER MARKS

- ↑ The Washington Post: "Ford's Theatre Museum To Unveil New Artifacts" July 9, 2009

- ↑ The Washington Post: "Ford's Theatre Museum Reopens; New Displays Focus on Lincoln's Life" July 17, 2009. BY MICHAEL O'SULLIVAN

- ↑ Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- ↑ Petersen House

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ford's Theatre. |

- Official NPS website: Ford's Theatre National Historic Site

- Ford's Theatre Society including Center for Education and Leadership, Theatre Box Office

- The 1893 collapse of Ford's Theatre

- Abraham Lincoln's Assassination

- The Life and Plot of John Wilkes Booth

- Podcast with the curator of Ford's Theatre from the Speaking of History Podcast - MP3 file

- Podcast of the Ranger Talk for visitors from Ford's Theatre from the Speaking of History Podcast

- Ford's Theatre at Google Cultural Institute

- "A Living Museum" (Slideshow). The New York Times. July 15, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2009.