Toxopneustes pileolus

| Flower urchin | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Flower urchin from Okinawa, Japan | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Echinodermata |

| Class: | Echinoidea |

| Superorder: | Echinacea |

| Order: | Camarodonta |

| Infraorder: | Temnopleuridea |

| Family: | Toxopneustidae |

| Genus: | Toxopneustes |

| Species: | T. pileolus |

| Binomial name | |

| Toxopneustes pileolus (Lamarck, 1816) | |

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Toxopneustes pileolus, commonly known as the flower urchin, is a widespread and commonly encountered species of sea urchin from the Indo-West Pacific. It is considered highly dangerous, as it is capable of delivering extremely painful and medically significant stings when touched. It inhabits coral reefs, seagrass beds, and rocky or sandy environments at depths of up to 90 m (295 ft). It feeds on algae, bryozoans, and organic detritus.

Its common name is derived from its numerous and distinctively flower-like pedicellariae, which are usually pinkish-white to yellowish-white in color with a central purple dot. It possesses short and blunt spines, though these are commonly hidden beneath the pedicellariae. The rigid "shell" (test) is a variegated deep red and gray in color, though in rare cases it may be greenish to light purple.

Taxonomy

Toxopneustes pileolus is one of four species belonging to the genus Toxopneustes. It belongs to the family Toxopneustidae in the order Camarodonta. It was originally described as Echinus pileolus by the French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck in 1816, in the second book of his Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres series. It was later used as the type species for the newly created genus Toxopneustes by the Swiss American biologist Louis Agassiz.[1]

The generic name Toxopneustes literally means "poison breath", derived from Greek τοξικόν [φάρμακον] (toksikón [phármakon], "arrow [poison]") and πνευστος (pneustos, "breath"). The specific name pileolus means "little cap" or "skullcap", from Latin pileus, a kind of brimless conical felt cap. In English, Toxopneustes pileolus is most widely known as the "flower urchin".[1] It is also sometimes known under various other common names, including "trumpet sea urchin",[2] "flower tip urchin",[3] "felt cap sea urchin",[4] and "poison claw sea urchin".[5] In the seashell collecting trade, Toxopneustes pileolus is known as the "mushroom urchin", due to their spineless empty shells (tests) resembling the caps of mushrooms.[6][7]

It is also known as tapumiti in Samoan;[8] tehe-tehe batu in Sinama and Tausug;[9] rappa-uni (ラッパウニ) or dokugaze (毒ガゼ) in Japanese;[1][10] and lǎbā dú jí hǎi dǎn (喇叭毒棘海膽) in Chinese.[11]

Description

Flower urchins are relatively large sea urchins. They can reach a maximum diameter of around 15 to 20 cm (6 to 8 in).[12][13]

.jpg)

Like most echinoderms, the body of adult flower urchins is equally divided into identical segments around a central axis in multiples of five (pentaradial symmetry). The rigid "shell" (test) has five interambulacral segments separated from each other by five ambulacral segments, each of them are composed of smaller regularly interlocking plates. It is overlaid by a thin layer of skin in living individuals. The test is variegated in coloration, usually deep red and grey, though there are rare instances of green and pale purple.[14][15][16] Each ambulacral segment is ornamented by a large purple zigzag pattern running along its length.[14]

Two rows of tube feet emerge from the grooves on either side of each of the ambulacral segments (for a total of ten rows). The tube feet are individually composed of a thin muscular stalk (podia) tipped with a small suction cup (ampulla). The mouth is centrally located in the bottom (oral) surface of the test. It is surrounded by a ring of small plates overlaid by softer tissue known as the peristome. Embedded in the peristome are five calcareous "teeth" collectively known as Aristotle's lantern. These are used for grinding the flower urchin's food. The anus is situated on the upper (aboral) surface of the test, directly opposite the mouth. Like the mouth, it is surrounded by a ring of small plates known as the periproct. Surrounding the anal opening are five smaller holes (the genital pores) which are directly connected to the gonads inside the body cavity.[14][15]

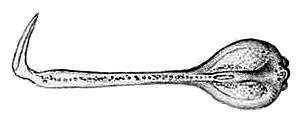

The most conspicuous feature of flower urchins are their pedicellariae (stalked grasping appendages). Flower urchins possess four types of pedicellariae, distinguished by form and function, but only two are abundant. The first type are the ophicephalous pedicellariae. They resemble tube feet, except they end in three small claws (called valves) rather than suction cups. These are used to keep the body surface clear of algae, encrusting organisms, and unwanted debris.[16][17][18][19]

The second type are the globiferous pedicellariae which superficially resemble flowers (hence its common name).[21] These are more specialized and are used for defense against predators and larger ectoparasites. Globiferous pedicellariae also end in a three-valved claw-like grasping appendage, like they do in ophicephalous pedicellariae, but they are much larger.[19][22] The valves are connected to each other by a distinctive circular membrane around 4 to 5 mm (0.16 to 0.20 in) in diameter. They are pinkish-white to yellowish-white in color with a central purple dot and a bright white rim.[14][19] Each valve ends in a sharp fang-like tip which is capable of penetrating human skin.[18][23][24] The base of the valves also house venom glands.[19][25] Some authors further subdivide globiferous pedicellariae into two subtypes based on size - the trumpet pedicellariae and the giant pedicellariae.[21] The other two types of pedicellariae - tridentate and triphyllous - are rare or restricted only to certain areas of the test.[16]

The relatively blunt spines are quite short and are usually hidden below the flower-like pedicellariae. They can vary from white, pink, yellow, light green, to purple in coloration with lighter-colored tips.[14][15]

Other members of the genus Toxopneustes are similar in appearance and can be mistaken for flower urchins. Toxopneustes roseus can be distinguished by the uniform coloration of their tests of pink, brown, or purple. It is also restricted to the East Pacific and thus aren't found together with flower urchins. Toxopneustes elegans, which is only found around Japan, can be distinguished by the presence of a distinctive dark stripe just below the tips of their spines. Toxopneustes maculatus is a very rare species known only from specimens from Réunion, Christmas Island, and the Palmyra Atoll. It can be distinguished by the bright violet coloration on the bottom and in a band around the middle of their tests.[15]

Distribution and habitat

Flower urchins are widespread and common in the tropical Indo-West Pacific.[12] They can be found north from Okinawa, Japan, to Tasmania, Australia in the south;[17][26] and west from the Red Sea and the East African coast,[1] to Raratonga in the Cook Islands in the east.[27]

They are found among coral reefs, coral rubble, rocks, sand, and seagrass beds at depths of 0 to 90 m (0 to 295 ft) from the water's surface.[12][28] They may sometimes partially bury themselves on the substrate.[17]

Ecology and behavior

Diet

Flower urchins feed on algae, bryozoans, and organic detritus.[26][29]

Predators

Flower urchins have few predators.[17] They are known to be toxic to fish. One of the few organisms capable of consuming flower urchins with no apparent adverse effects is the predatory corallimorph Paracorynactis hoplites. However it is unknown if flower urchins are among its natural prey.[30]

Associated species

The commensal alpheid shrimp Athanas areteformis, can sometimes be found living among the spines of flower urchins (as well as burrowing urchins and collector urchins).[31] The intestines of flower urchins can also serve as habitats for the commensal flatworm Syndesmis longicanalis.[32]

Flower urchins are also common hosts of the zebra crab, Zebrida adamsii. These tiny crabs are obligate symbionts of sea urchins. They cling to the spines on the outer surface of the sea urchin test using their highly specialized walking legs. Because their ability to walk on substrates like sand is impaired, zebra crabs spend their entire benthic life stage attached to sea urchins, switching between hosts only during the mating season. Usually only one zebra crab is attached to an individual sea urchin outside of the mating season, but larger sea urchins can be hosts to two (very rarely more). The area of the test they inhabit is characteristically smooth; completely devoid of spines, pedicellariae, tube feet, and even epidermis. It is unknown if they physically destroy and/or consume these appendages or if they use other stimuli to induce the host sea urchins to autotomize. Although previously considered harmless commensals, authors have since reclassified them as parasites. In addition to the visible external damage, a 1974 study also observed abnormal behavior and coloration among infected sea urchins. They also appear to be immune to the flower urchin's venom.[10][33][34]

Reproduction

Flower urchins are dioecious (having separate male and female individuals), but it is almost impossible to determine the sex of an individual by external characteristics alone. A possible method is by examining the external characteristics of the genital pores (gonopores). In males, they are generally short, cone-shaped, and extrude above the body surface; while in females they are usually sunken. However this is not reliable, as 15% of the cases can exhibit the opposite characteristics. All other external features, like shape and size of the tests or color of the spines are indistinguishable between the two sexes.[35] Flower urchins have a chromosome number of 2n = 42.[36]

Relatively little is known of the spawning behavior of flower urchins. Like other sea urchins, fertilization happens externally. Males and females release free-swimming gametes (eggs and sperm) directly into the water currents in mass spawning events.[37] In Okinawa, Japan, a 1994 study identified the spawning season of flower urchins as occurring in winter, at the same time as the closely related and sympatric Toxopneustes elegans. It also recorded possible natural hybrids resulting from instances where the eggs of Toxopneustes pileolus are fertilized by the sperm of Toxopneustes elegans.[38]

In Taiwan, a 2010 study observed flower urchins spawning in May on the years 2007 and 2009. They occurred on highly similar conditions: in the afternoon low tide of the spring tide immediately after a new moon. During the event, spawning individuals discard the debris that usually cover their bodies before releasing their gametes into the water.[37] Another study published in 2013 did not find any obvious correlation between lunar and tidal cycles to the mass spawning behavior of the flower urchin populations in southern Taiwan. It did note that the spawning patterns appeared to be non-random, with higher spawning rates on daytime on certain dates. However, the study was conducted within a span of only five months (from April to August 2010).[39]

"Covering" behavior

Flower urchins are among the numerous species of sea urchins known as "collector urchins", so named because they frequently cover the upper surfaces of their bodies with debris from their surroundings. This behavior is usually referred to as "covering" or "heaping".[28][33][40] Flower urchins are usually found almost completely covered in objects like dead coral fragments, shells, seaweed, and rocks.[17][41] These are held fast to their bodies using their tube feet and pedicellariae.[37]

The function of this behavior is not well understood. Some authors believe that the debris serve as ballast, preventing them from being swept away by wave surges when feeding;[37][42] while others believe that they may function as some sort of defense against predation.[33] A 2007 study has hypothesized that the behavior may serve as protection from UV radiation during daytime.[43]

Venom

Bioactive components

At least two active toxins have been purified from the pedicellarial venom of flower urchins in two studies.[44] The first was discovered in 1991 and named Contractin A. It was found to interfere with the transmission of signals at nerve endings as well as cause hemagglutination (clumping of the red blood cells).[45][46] When administered to guinea pigs, it resulted in contractions in the smooth muscles.[47]

The second, discovered in 1994, is a protein toxin named peditoxin. It is composed of the protein pedin and the active prosthetic group pedoxin. At low doses to mice, pedoxin was found to result in markedly lower body temperatures, muscle relaxation, sedation, and anesthetic coma. At higher doses it resulted in convulsions and death. Pedin itself is non-toxic, but it magnifies the effects of pedoxin. When combined together into the holoprotein peditoxin, even low doses resulted in anaphylaxis-like shock and death.[48]

UT841, a possible third toxin isolated in 2001, has been shown to affect brain metabolism in chicks. However, the authors are unclear on whether UT841 may actually be the same compound as Contractin A, since both have the same molecular weight of 18,000 Da and an almost identical N-terminal sequence.[49]

In addition to these toxins, lectins have also been isolated from flower urchin venom. Among them is SUL-I, SUL-II, SUL-IA, and SUL-III (SUL stands for "sea urchin lectin"). These lectins may be valuable as research tools for investigating the functions of cell processes.[50]

Envenomation mechanism

Unlike most other venomous sea urchins, flower urchins and related toxopneustids do not deliver their venom through spines. Instead, the venom is administered through the flower-like globiferous pedicellariae.[18][23][24][25] If undisturbed, the tips of the globiferous pedicellariae are usually expanded into round cup-like shapes. They possess tiny sensors on their inside surfaces which can detect threats by touch and chemical stimuli. When agitated or brushed against by a potential threat, the pedicellariae will immediately snap shut and inject venom. The claws of the pedicellariae may also break off from their stalks and adhere to the point of contact, retaining the ability to continually inject venom for several hours.[4][33][51][52]

The potency of the pedicellarial venom is believed to be directly related to the size of the pedicellariae. Thus individuals with larger globiferous pedicellariae are considered to be more dangerous than individuals with more numerous but smaller globiferous pedicellariae.[21]

Effects on humans

In 1930, the Japanese marine biologist Tsutomu Fujiwara accidentally envenomated himself with seven or eight flower urchin pedicellariae while working in a fishing boat. He described his experience in a paper published in 1935:[33][51][52]

On June 26, 1930, while I was working on a fishing boat on the coast of Tsutajima in Saganoseki, I scooped up with my bare hand an individual of the sea-urchin which had been carried up by a diver with a fishing implement on the water surface from the sea-bottom about 20 fathoms in depth, and I transferred the sea-urchin into a small tank in the boat. At that time, 7 or 8 pedicellariae stubbornly attached themselves to a side of the middle finger of my right hand, detached from the stalk and remained on the skin of my finger.

Instantly, I felt a severe pain resembling that caused by the cnidoblast of Coelenterata, and I felt as if the toxin were beginning to move rapidly to the blood vessel from the stung area towards my heart. After a while, I experienced a faint giddiness, difficulty of respiration, paralysis of the lips, tongue and eyelids, relaxation of muscles in the limbs, was hardly able to speak or control my facial expression, and felt almost as if I were going to die. About 15 minutes afterwards, I felt that pains gradually diminish and after about an hour they disappeared completely. But the facial paralysis like that caused by cocainization continued for about six hours.

Tsutomu Fujiwara (1935). "On the poisonous pedicellaria of Toxopneustes pileolus (Lamarck)". Annotationes Zoologicae Japonenses. 15 (1): 62–68.

There have been reports of fatalities resulting from flower urchin envenomation.[53] One such report was the purported drowning of a pearl diver after being rendered unconscious from accidental contact with a flower urchin.[54][55][56] But it remains difficult to confirm if these incidents actually occurred since no documentation or details of the deaths have been uncovered so far.[54][57]

Nevertheless, flower urchins are still considered highly dangerous. The severe debilitating pain of the flower urchin sting compounded by muscular paralysis, breathing problems, numbness, and disorientation can result in accidental drowning among divers and swimmers.[4][18][58] The flower urchin was named the "most dangerous sea urchin" in the 2014 Guinness World Records.[59]

Edibility

Despite being venomous, flower urchins are sometimes harvested in East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific Islands for their edible gonads.[8][9][60][61] In the Sulu Archipelago of the Philippines and eastern Sabah, Malaysia, flower urchins are among the species of edible sea urchins used by the Sama-Bajau and Tausug people to make a traditional delicacy known as oku-oku or ketupat tehe tehe. This is prepared by degutting the test and then filling it with glutinous rice and coconut milk before boiling.[9]

Other uses

In Okinawa, fishermen observed numerous individuals of the predatory crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) gathering around the remains of the internal organs of flower urchins.[62] A follow-up study by Japanese researchers in 2001 confirmed that the viscera of flower urchins could indeed attract crown-of-thorns starfish in both aquarium and open sea experiments. The attractant compounds were isolated and identified as arachidonic acid and α-linolenic acid. The authors believe that this discovery may be used to augment population control measures of the crown-of-thorns starfish, which are highly destructive to coral reefs.[63]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Andreas Kroh (2014). A. Kroh & R. Mooi, eds. "Toxopneustes pileolus (Lamarck, 1816)". World Echinoidea Database. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ S. Amemiya (2002). "Developmental modes and rudiment formation in sea urchins". In Yukio Yokota; Valeria Matranga; Zuzana Smolenicka. The Sea Urchin: From Basic Biology to Aquaculture. CRC Press. p. 37. ISBN 9789058093790.

- ↑ "Flower Urchin (Toxopneustes pileolus)". WHATSTHATFISH. 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Gordon C. Cook; Alimuddin Zumla (2008). Manson's Tropical Diseases. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 586. ISBN 9780702043321.

- ↑ Rokus Groeneveld; Sanne Reijs (2014). "Echinoderms, sea urchins". Diverosa. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ Richard Howey (2005). "Calcareous Flowers: Tests and Cross-Sections of Sea Urchin Spines". Microscopy UK. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ↑ "Sea Urchin - Mushroom". Paxton Gate. 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- 1 2 Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (2010). State of the Environment Report 2006 (PDF). Government of Samoa.

- 1 2 3 Siti Akmar Khadijah Ab Rahim & Raymie Nurhasan (2012). "Edible sea urchin species in Sabah Waters" (PDF). Research Bulletin, Faculty of Resource Science and Technology. 1: 2–3.

- 1 2 Katsumi Suzuki; Masatsune Takeda (1974). "On a parthenopid crab, Zebrida adamsii on the sea urchins from Suruga Bay, with a special reference to their parasitic relations" (PDF). Bulletin of the National Science Museum. 17 (4): 286–296.

- ↑ "Toxopneustes pileolus (Lamarck, 1816)". The Global Biodiversity Information Facility: GBIF Backbone Taxonomy. July 1, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- 1 2 3 M.L.D. Palomares; D. Pauly., eds. (2014). "Toxopneustes pileolus (Lamarck, 1816)". SeaLifeBase. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Flower Urchin (Toxopneustes pileolus)". Lord Howe Island Museum. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Frédéric Ducarme (2014). "Toxopneustes pileolus - Brief Summary". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Hubert Lyman Clark (1925). A Catalogue of the Recent Sea-Urchins (Echinoidea) in the Collection of the British Museum (Natural History). Oxford University Press. pp. 122–123.

- 1 2 3 Alexander Agassiz; Hubert Lyman Clark (1912). "Hawaiian and Other Pacific Echini: The Pedinidae, Phymosomatidae, Stomopneustidae, Echinidae, Temnopleuridae, Strongylocentrotidae, and Echinometridae". Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoölogy at Harvard College. 34 (4): 207–383. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.3820.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Marine Animal Encyclopedia (2014). "Flower Urchin Toxopneustes pileolus". Oceana. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Flower urchin has one hell of a nasty sting...". Destination-Scuba. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Simon E. Coppard; Andreas Kroh; Andrew B. Smith (2010). "The evolution of pedicellariae in echinoids: an arms race against pests and parasites" (PDF). Acta Zoologica. 20: 1–24. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6395.2010.00487.x.

- ↑ Alexander Agassiz (1872). Revision of the Echini. Illustrated Catalogue of the Museum of Comparative Zoölogy at Harvard College. Cambridge University Press.

- 1 2 3 H. Nakagawa; T. Hashimoto; H. Hayashi; M. Shinohara; K. Ohura; E. Tachikawa; T. Kashimoto (1996). "Isolation of a novel lectin from the globiferous pedicellariae of the sea urchin Toxopneustes pileolus". Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 391: 213–223. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-0361-9_14.

- ↑ Ole Theodor Jensen Mortensen (1903). The Danish Ingolf-Expedition Volume IV Part 1. H. Hagerup. p. 135–136.

- 1 2 Kozue Edo (2014). Study on a pedicellarial venom lectin from the sea urchin Toxopneustes pileolus, in the coast of Tokushima Prefecture, Japan (PDF). Graduate School of Integrated Arts and Sciences, The University of Tokushima.

- 1 2 Ronald L. Shimek (1997). "There is No Reason to Be Spineless". Reefs.org. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- 1 2 Pedro Nuño Ferreira. "When Beauty Turns to Beast And Hell Breaks Loose in the Reef System". Reefs Magazine. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- 1 2 Andrew Trevor-Jones (2008). "Toxopneustes pileolus". ATJ's Marine Aquarium Site. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ↑ Gerald McCormack (2007). "Toxopneustes pileolus Flower Urchin". Cook Islands Biodiversity Database, Version 2007.2. Cook Islands Natural Heritage Trust. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- 1 2 M. de Beer (1990). "Distribution patterns of regular sea urchins (Echinodermata: Echinoidea) across the Spermonde Shelf, SW Sulawesi (Indonesia)". In C. De Ridder; P. Dubois; M.-C. Lahaye; M. Jangoux. Echinoderm Research. CRC Press. pp. 165–169. ISBN 9789061911418.

- ↑ Bob Goemans (2012). "Toxopneustes pileolus". Saltcorner. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ↑ Arthur R. Bos; Benjamin Mueller; Girley S. Gumanao (2011). "Feeding biology and symbiotic relationships of the corallimorpharian Paracorynactis hoplites (Anthozoa: Hexacorallia)" (PDF). The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 59 (2): 245–250.

- ↑ Andreas Kroh (2014). A. Kroh & R. Mooi, eds. "Echinometra mathaei (Blainville, 1825)". World Echinoidea Database. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ Jozef B. Moens; Els E. Martens; Ernest R. Schockaert (1994). "Syndesmis longicanalis sp. nov., an umagillid turbellarian (Platyhelminthes) from echinoids from the Kenyan coast" (PDF). Belgian Journal of Zoology. 124 (2): 105–114.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Christopher Mah (February 4, 2014). "What we know about the world's most venomous sea urchin Toxopneustes fits in this blog post!". Echinoblog. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ Yasunobu Yanagisawa; Akira Hamaishi (1986). "Mate acquisition by a solitary crab Zebrida adamsii, a symbiont of the sea urchin". Journal of Ethology. 4 (2): 153–162. doi:10.1007/BF02348117.

- ↑ Yutaka Tahara; Minoru Okada; Naomasa Kobayashi (1958). "Secondary sexual characters in Japanese sea-urchins" (PDF). Publications of the Seto Marine Biological Laboratory. 7 (1): 165–172.

- ↑ T. Uehara; M. Shingaki; K. Taira; Y. Arakaki; H. Nakatomi (1991). "Chromosome studies in eleven Okinawan species of sea urchins, with special reference to four species of the Indo-Pacific Echinometra". In T. Yanagisawa; I. Yasumasu; C. Oguro; N. Suzuki; T. Motokawa. Biology of Echinodermata: Proceedings of the 7th International Echinoderm Conference, Japan (Atami) 9th - 14th September 1990. CRC Press. pp. 119–129. ISBN 9789054100102.

- 1 2 3 4 Andy Chen; Keryea Soong (2010). ""Uncovering" behavior at spawning of the trumpet sea urchin Toxopneustes pileolus" (PDF). Zoological Studies. 49 (1): 9.

- ↑ K. Fukuchi; T. Uehara (1994). "Hybridization between species of sea urchins Toxopneustes elegans and Toxopneustes pileolus". In Bruno David; Alain Guille; Jean-Pierre Feral; Michel Roux. Echinoderms Through Time. CRC Press. p. 669. ISBN 9789054105145.

- ↑ Shi-jie Lin (2013). Are there lunar patterns of gamete release in two sea urchins (Toxopneustes pileolus and Tripneustes gratilla)? (M.Sc.). Institute of Marine Biology, National Sun-Yat-sen University.

- ↑ Yasunobu Yanagisawa (1972). "Preliminary observations on the so-called heaping behaviour in a sea urchin, Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus (A. Agassiz)" (PDF). Publications of the Seto Marine Biological Laboratory. 9 (6): 431–435.

- ↑ Peter Frances; et al., eds. (2014). Ocean: The Definitive Visual Guide. Dorling Kindersley. p. 310. ISBN 9781465436207.

- ↑ D. W. James (2000). "Diet, movement, and covering behavior of the sea urchin Toxopneustes roseus in rhodolith beds in the Gulf of California, México". Marine Biology. 137: 913–923. doi:10.1007/s002270000423.

- ↑ Jessica E. Sigg; Karena M. Lloyd-Knight; Jean Geary Boal (2007). "UV radiation influences covering behaviour in the urchin Lytechinus variegatus". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 87 (5): 1257–1261. doi:10.1017/s0025315407055865.

- ↑ Yukio Yokota (2005). "Bioresources from Echinoderms". In Valeria Matranga. Echinodermata. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 257. ISBN 9783540244028.

- ↑ Aaron Sewell (September 2007). "Feature Article: Toxins, Venoms and Inhibitory Chemicals in Marine Organisms". Advanced Aquarist Volume IV. CoralScience.org. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ↑ Randy Holmes-Farley (2008). "Sea Urchins: A Chemical Perspective". Reefkeeping. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ↑ H. Nakagawa; A.T. Tu; A. Kimura (1991). "Purification and characterization of Contractin A from the pedicellarial venom of sea urchin, Toxopneustes pileolus". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 284 (2): 279–284. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(91)90296-u. PMID 1989511.

- ↑ S. Kuwabara (1994). "Purification and properties of peditoxin and the structure of its prosthetic group, pedoxin, from the sea urchin Toxopneustes pileolus (Lamarck)". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 269 (43): 26734–26738. PMID 7929407.

- ↑ Y. Zhang; J. Abe; A. Siddiq; H. Nakagawa; S. Honda; T. Wada; S. Ichida (2001). "UT841 purified from sea urchin (Toxopneustes pileolus) venom inhibits time-dependent (45)Ca(2+) uptake in crude synaptosome fraction from chick brain". Toxicon. 39 (8): 1223–1229. doi:10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00267-1. PMID 11306134.

- ↑ Hitomi Sakai; Kozue Edo; Hideyuki Nakagawa; Mitsuko Shinohara; Rie Nishiitsutsuji; Kiyoshi Ohura (2013). "Isolation and partial characterization of a L-rhamnose-binding lectin from the globiferous pedicellariae of the toxopneustid sea urchin, Toxopneustes pileolus" (PDF). International Aquatic Research. 5 (12): 1–10.

- 1 2 Bruce W. Halstead (2013). "Venomous Echinoderms and Annelids". In Wolfgang Bücherl; Eleanor E. Buckley. Venomous Animals and Their Venoms: Volume III - Venomous Invertebrates. Academic Press, Inc. pp. 427–431. ISBN 9781483262895.

- 1 2 Tsutomu Fujiwara (1935). "On the poisonous pedicellaria of Toxopneustes pileolus (Lamarck)". Annotationes Zoologicae Japonenses. 15 (1): 62–68.

- ↑ Frederick W. Oehme; Daniel E. Keyler (2007). "Plant and Animal Toxins". In A. Wallace Hayes. Principles and Methods of Toxicology, Fifth Edition. CRC Press. p. 1012. ISBN 9780849337789.

- 1 2 John A. Williamson; Joseph W. Burnett; Peter J. Fenner; Jacquie F. Rifkin (1996). Venomous and Poisonous Marine Animals: A Medical and Biological Handbook. UNSW Press. p. 322. ISBN 9780868402796.

- ↑ Scott A. Gallagher. "Echinoderm Envenomation Clinical Presentation". Medscape. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ Elizabeth Mitchell; Ron Medzon (2005). Introduction to Emergency Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 513. ISBN 9780781732000.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2003). "Dangerous Aquatic Organisms". Guidelines for safe recreational water environments. Volume 1: Coastal and fresh waters (PDF). World Health Organization. p. 184. ISBN 9241545801.

- ↑ William J Dahl; Peter Jebson; Dean S Louis (2010). "Sea urchin injuries to the hand: a case report and review of the literature". Iowa Orthopaedic Journal. 30: 153–156. PMC 2958287

. PMID 21045988.

. PMID 21045988. - ↑ Craig Glenday, ed. (2014). Guinness World Records 2014. Bantam. p. 30. ISBN 9780553390551.

- ↑ Takasi Tokioka (1963). "Supposed effects of the cold weather of the winter 1962–63 upon the intertidal fauna in the vicinity of Seto" (PDF). Publications of the Seto Marine Biological Laboratory. 11 (2): 415–424.

- ↑ Shyh-Min Chao; Bang-Chin Chen (2012). "High density of flower urchin, Toxopneustes pileolus, in Houbihu Lagoon, Southern Taiwan". Platax. 9: 77–81.

- ↑ Daisuke Uemura (2010). "Exploratory research on bioactive natural products with a focus on biological phenomena". Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B: Physical and Biological Sciences. 86 (3): 190–201. doi:10.2183/pjab.86.190. PMC 3417845

. PMID 20228620.

. PMID 20228620. - ↑ Toshiaki Teruya; Kiyotake Suenaga; Tomoyuki Koyama; Yoshikatsu Nakano; Daisuke Uemura (2001). "Arachidonic acid and α-linolenic acid, feeding attractants for the crown-of-thorns sea star Acanthaster planci, from the sea urchin Toxopneustes pileolus". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 266 (2): 123–134. doi:10.1016/S0022-0981(01)00337-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Toxopneustes pileolus. |

- Christopher Mah (February 4, 2014). "What we know about the world's most venomous sea urchin Toxopneustes fits in this blog post!". Echinoblog.

- Video of a live flower urchin in its natural habitat (YouTube)

- Video of a live captive flower urchin (YouTube)

- Video of a flower urchin with a zebra crab (YouTube)