Flight 19

Artist's depiction of the five Grumman TBM Avengers that disappeared | |

| Occurrence summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | December 5, 1945 |

| Summary | Disappearance |

| Site | Unknown |

| Crew | 14 |

| Fatalities | 14 (assumed) |

| Survivors | none known |

| Aircraft type | Grumman TBM Avenger |

| Operator |

|

| Destination | NAS Fort Lauderdale |

Flight 19 was the designation of five Grumman TBM Avenger torpedo bombers that disappeared over the Bermuda Triangle on December 5, 1945 after losing contact during a United States Navy overwater navigation training flight from Naval Air Station Fort Lauderdale, Florida. All 14 airmen on the flight were lost, as were all 13 crew members of a Martin PBM Mariner flying boat that subsequently launched from Naval Air Station Banana River to search for Flight 19. The PBM aircraft was known to collect flammable aviation gasoline vapors in its bilges and professional investigators have assumed that the PBM most likely exploded in mid-air while searching for the flight. Navy investigators could not determine the cause of the loss of Flight 19.

Navigation training flight

Flight 19 undertook a routine navigation and combat training exercise in TBM-type aircraft.[1] The assignment was called "Navigation problem No. 1", a combination of bombing and navigation, which other flights had completed or were scheduled to undertake that day.[2] The flight leader was United States Navy Lieutenant Charles Carroll Taylor, who had about 2,500 flying hours, mostly in aircraft of this type, while his trainee pilots each had 300 total, and 60 flight hours in the Avenger.[2] Taylor had completed a combat tour in the Pacific theatre as torpedo bomber pilot on the aircraft carrier USS Hancock and had recently arrived from NAS Miami where he had also been a VTB instructor. The student pilots had recently completed other training missions in the area where the flight was to take place.[2] They were US Marine Captains Edward Joseph Powers and George William Stivers, US Marine Second Lieutenant Forrest James Gerber and USN Ensign Joseph Tipton Bossi; their callsigns started with 'Fox Tare'.

The aircraft were four TBM-1Cs, BuNo 45714, 'FT3', BuNo 46094, 'FT36', BuNo 46325, 'FT81', BuNo 73209, 'FT117', and one TBM-3, BuNo 23307, 'FT28'. Each was fully fueled, and during pre-flight checks it was discovered they were all missing clocks. Navigation of the route was intended to teach dead reckoning principles, which involved calculating among other things elapsed time. The apparent lack of timekeeping equipment was not a cause for concern as it was assumed each man had his own watch. Takeoff was scheduled for 13:45 local time, but the late arrival of Taylor delayed departure until 14:10. Weather at NAS Fort Lauderdale was described as "favorable, sea state moderate to rough."[2] Taylor was supervising the mission, and a trainee pilot had the role of leader out front.

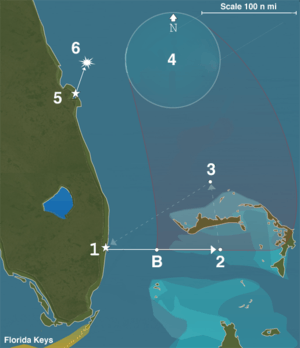

Called "Naval Air Station, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, navigation problem No. 1,"[3] the exercise involved three different legs, but the actual flight should have flown four. After take off, they flew on heading 091° (almost due east) for 56 nmi (64 mi; 104 km) until reaching Hen and Chickens Shoals where low level bombing practice was carried out. The flight was to continue on that heading for another 67 nmi (77 mi; 124 km) before turning onto a course of 346° for 73 nmi (84 mi; 135 km), in the process over-flying Grand Bahama island. The next scheduled turn was to a heading of 241° to fly 120 nmi (140 mi; 220 km) at the end of which the exercise was completed and the Avengers would turn left to then return to NAS Ft. Lauderdale.[2]

1. Leave NAS Fort Lauderdale 14:10 on heading 091°, drop bombs at Hen and Chickens shoals (B) until about 15:00 then continue on heading 091° for 73 nautical miles (140 km)

2. Turn left to heading 346° and fly 73 nautical miles (140 km).

3. Turn left to heading 241° for 120 nautical miles (220 km) to end exercise north of NAS Fort Lauderdale.

4. 17:50 radio triangulation establishes flight's position to within 50 nautical miles (93 km) of 29°N 79°W / 29°N 79°W and their last reported course, 270°.

5. PBM Mariner leaves NAS Banana River 19:27.

6. 19:50 Mariner explodes near 28°N 80°W / 28°N 80°W.

Radio conversations between the pilots were overheard by base and other aircraft in the area. The practice bombing operation is known to have been carried out because at about 15:00 a pilot requested and was given permission to drop his last bomb.[2] Forty minutes later, another flight instructor, Lieutenant Robert F. Cox in FT-74, forming up with his group of students for the same mission, received an unidentified transmission.[3]

An unidentified crew member asked Powers, one of the students, for his compass reading. Powers replied: "I don't know where we are. We must have got lost after that last turn." Cox then transmitted; "This is FT-74, plane or boat calling 'Powers' please identify yourself so someone can help you." The response after a few moments was a request from the others in the flight for suggestions. FT-74 tried again and a man identified as FT-28 (Taylor) came on. "FT-28, this is FT-74, what is your trouble?" "Both of my compasses are out", Taylor replied, "and I am trying to find Fort Lauderdale, Florida. I am over land but it's broken. I am sure I'm in the Keys but I don't know how far down and I don't know how to get to Fort Lauderdale."[2]

FT-74 informed the NAS that aircraft were lost, then advised Taylor to put the sun on his port wing and fly north up the coast to Fort Lauderdale. Base operations then asked if the flight leader's aircraft was equipped with a standard YG (IFF transmitter), which could be used to triangulate the flight's position, but the message was not acknowledged by FT-28. (Later he would indicate that his transmitter was activated.) Instead, at 16:45, FT-28 radioed: "We are heading 030 degrees for 45 minutes, then we will fly north to make sure we are not over the Gulf of Mexico." During this time no bearings could be made on the flight, and IFF could not be picked up. Taylor was told to broadcast on 4805 kilocycles. This order was not acknowledged so he was asked to switch to 3,000 kilocycles, the search and rescue frequency. Taylor replied – "I cannot switch frequencies. I must keep my planes intact."[2]

At 16:56, Taylor was again asked to turn on his transmitter for YG if he had one. He did not acknowledge but a few minutes later advised his flight "Change course to 090 degrees (due east) for 10 minutes." About the same time someone in the flight said "Dammit, if we could just fly west we would get home; head west, dammit."[2] This difference of opinion later led to questions about why the students did not simply head west on their own.[4] It has been explained that this can be attributed to military discipline.[4]

As the weather deteriorated, radio contact became intermittent, and it was believed that the five aircraft were actually by that time more than 200 nmi (230 mi; 370 km) out to sea east of the Florida peninsula. Taylor radioed "We'll fly 270 degrees west until landfall or running out of gas" and requested a weather check at 17:24. By 17:50 several land-based radio stations had triangulated Flight 19's position as being within a 100 nmi (120 mi; 190 km) radius of 29°N 79°W / 29°N 79°W; Flight 19 was north of the Bahamas and well off the coast of central Florida, but nobody transmitted this information on an open, repetitive basis.

At 18:04, Taylor radioed to his flight "Holding 270, we didn't fly far enough east, we may as well just turn around and fly east again". By that time, the weather had deteriorated even more and the sun had since set. Around 18:20, Taylor's last message was received. (It has also been reported that Taylor's last message was received at 19:04.)[5] He was heard saying "All planes close up tight ... we'll have to ditch unless landfall ... when the first plane drops below 10 gallons, we all go down together."[1][2]

PBM-5 (Bureau Number 59225)

A Martin PBM-5 Mariner similar to BuNo 59225.[6]) | |

| Occurrence summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | December 5, 1945 |

| Summary | Disappearance, Presumed mid-air explosion |

| Site | 28°35′N 80°15′W / 28.59°N 80.25°W |

| Crew | 13 |

| Fatalities | 13 |

| Survivors | none |

| Aircraft type | Martin PBM-5 Mariner |

| Operator |

|

| Flight origin | NAS Banana River |

| Destination | NAS Banana River |

As it became obvious the flight was lost, air bases, aircraft, and merchant ships were alerted. A Consolidated PBY Catalina departed after 18:00 to search for Flight 19 and guide them back if they could be located. After dark, two Martin PBM Mariner seaplanes originally scheduled for their own training flights were diverted to perform square pattern searches in the area west of 29°N 79°W / 29°N 79°W. PBM-5 BuNo 59225 took off at 19:27 from Naval Air Station Banana River (now Patrick Air Force Base), called in a routine radio message at 19:30 and was never heard from again.[2]

At 21.15, the tanker SS Gaines Mills reported it had observed flames from an apparent explosion leaping 100 ft (30 m) high and burning for 10 minutes, at position 28°35′N 80°15′W / 28.59°N 80.25°W. Captain Shonna Stanley reported unsuccessfully searching for survivors through a pool of oil and aviation gasoline. The escort carrier USS Solomons also reported losing radar contact with an aircraft at the same position and time.[2]

Investigation

A 500-page Navy board of investigation report published a few months later made several observations:

- Flight leader Lt. Charles C. Taylor had mistakenly believed that the small islands he passed over were the Florida Keys, so his flight was over the Gulf of Mexico and heading northeast would take them to Florida. It was determined that Taylor had passed over the Bahamas as scheduled, and he did in fact lead his flight to the northeast over the Atlantic. The report noted that some subordinate officers did likely know their approximate position as indicated by radio transmissions stating that flying west would result in reaching the mainland.

- Taylor was not at fault because the compasses stopped working.

- The loss of PBM-5 BuNo 59225 was attributed to an explosion.[3]

This report was subsequently amended "cause unknown" by the Navy after Taylor's mother contended that the Navy was unfairly blaming her son for the loss of five aircraft and 14 men, when the Navy had neither the bodies nor the airplanes as evidence.[7]

Had Flight 19 actually been where Taylor believed it to be, landfall with the Florida coastline would have been reached in a matter of 10 to 20 minutes or less, depending on how far down they were. However, a later reconstruction of the incident showed that the islands visible to Taylor were probably the Bahamas, well northeast of the Keys, and that Flight 19 was exactly where it should have been. The board of investigation found that because of his belief that he was on a base course toward Florida, Taylor actually guided the flight farther northeast and out to sea. Further, it was general knowledge at NAS Fort Lauderdale that if a pilot ever became lost in the area to fly a heading of 270° west (or in evening hours toward the sunset if the compass had failed). By the time the flight actually turned west, they were likely so far out to sea they had already passed their aircraft's fuel endurance. This factor combined with bad weather, and the ditching characteristics of the Avenger,[1] meant that there was little hope of rescue, even if they had managed to stay afloat.

It is possible that Taylor overshot Castaway Cay and instead reached another land mass in southern Abaco Island. He then proceeded northwest as planned. He fully expected to find the Grand Bahama Island lying in front of him as planned. Instead, he eventually saw a land mass to his right side, the northern part of Abaco Island. Believing that this landmass to his right was the Grand Bahama Island and his compass was malfunctioning, he set a course to what he thought was southwest to head straight back to Fort Lauderdale. However, in reality this changed his course farther northwest, toward open ocean.

To further add to his confusion, he encountered a series of islands north of Abaco Island, which looks very similar to the Key West Islands, but he was still over the ocean instead of over Fort Lauderdale. The control tower then suggested that Taylor's team should fly west, which would have taken them to the landmass of Florida eventually. Taylor headed for what he thought was west, but in reality was northwest, almost parallel to Florida.

After trying that for a while and no land in sight, Taylor decided that it was impossible for them to fly so far west and not reach Florida. He believed that he might have been near the Key West Islands. What followed was a series of serious confusions between Taylor, his team and the control tower. Taylor was not sure whether he was near Bahama or Key West, and he was not sure which direction was which due to compass malfunction. The control tower informed Taylor that he could not be in Key West since the wind that day did not blow that way. Some of his teammates believed that their compass was working. Taylor then set a course northeast according to their compass, which should take them to Florida if they were in Key West. When that failed, Taylor set a course west according to their compass, which should take them to Florida if they were in Bahama. If Taylor stayed this course he would have reached land before running out of fuel. However, at some point Taylor decided that he had tried going west enough. He then once again set a course northeast, thinking they were near Key West after all. Finally, his flight ran out of fuel and may have crashed into the ocean somewhere north of Abaco Island and east of Florida.[8]

Unrelated Avenger wreckage

In 1986, the wreckage of an Avenger was found off the Florida coast during the search for the wreckage of the Space Shuttle Challenger.[9] Aviation archaeologist Jon Myhre raised this wreck from the ocean floor in 1990. He mistakenly believed it was one of the missing planes.[10]

In 1991, a treasure-hunting expedition led by Graham Hawkes announced that the wreckage of five Avengers had been discovered off the coast of Florida, but that tail numbers revealed they were not Flight 19.[11][12] In 2004 a BBC documentary showed Hawkes returning with a new submersible 12 years later and identifying one of the planes by its bureau number (a clearly readable 23990[13]) as a flight lost at sea on 9 October 1943, over two years before Flight 19 (its crew all survived[14]), but he was unable to definitively identify the other planes; the documentary concluded that "Despite the odds, they are just a random collection of accidents that came to rest in the same place 12 miles from home."[15][13] But in March 2012 Hawkes was reported as stating that it had suited both him (and indirectly his investors) and the Pentagon to make the story go away because it was an expensive and time-consuming distraction, and that, while admitting he had found no conclusive evidence, he now thought he had in fact found Flight 19.[12]

Records showed training accidents between 1942 and 1945 accounted for the loss of 95 aviation personnel from NAS Fort Lauderdale[16] In 1992, another expedition located scattered debris on the ocean floor, but nothing could be identified. In the last decade, searchers have been expanding their area to include farther east, into the Atlantic Ocean, but the remains of Flight 19 have still never been confirmed found.

A wrecked warplane with two bodies inside was retrieved by the Navy In the mid-1960s near Sebastian, Florida. The Navy initially said it was from Flight 19 but later recanted its statement. Despite Freedom of Information Act requests for details in 2013,[17] the names are still not known because the Navy hasn't enough information to identify the bodies.

Crews of Flight 19 and PBM-5 BuNo 59225

Charles Carroll Taylor

The flight leader, Lieutenant Charles Carroll Taylor (born October 25, 1917), graduated from Naval Air Station Corpus Christi in February 1942 and became a flight instructor in October of that year.

| The men of Flight 19 and PBM-5 BuNo 59225[3] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Aircraft number | Pilot | Crew | Bureau Nr. (BuNo) |

| FT-28 | Charles C. Taylor, Lieutenant, USNR | George Devlin, AOM3c, USNR Walter R. Parpart, ARM3c, USNR |

23307 |

| FT-36 | E. J. Powers, Captain, USMC | Howell O. Thompson, SSgt, USMCR George R. Paonessa, Sgt, USMC |

46094 |

| FT-3 | Joseph T. Bossi, Ensign, USNR | Herman A. Thelander, S1c, USNR Burt E. Baluk, JR., S1c, USNR |

45714 |

| FT-117 | George W. Stivers, Captain, USMC | Robert P. Gruebel, Pvt, USMCR Robert F. Gallivan, Sgt, USMC |

73209 |

| FT-81* | Forrest J. Gerber, 2ndLt, USMCR | William E. Lightfoot, PFC, USMCR | 46325 |

| BuNo 59225 | Walter G. Jeffery, LTJG, USN | Harrie G. Cone, LTJG, USN Roger M. Allen, Ensign, USN Lloyd A. Eliason, Ensign, USN Charles D. Arceneaux, Ensign, USN Robert C. Cameron, RM3, USN Wiley D. Cargill, Sr., Seaman 1st, USN James F. Jordan, ARM3, USN John T. Menendez, AOM3, USN Philip B. Neeman, Seaman 1st, USN James F. Osterheld, AOM3, USN Donald E. Peterson, AMM1, USN Alfred J. Zywicki, Seaman 1st, USN |

59225 |

| * This particular plane was one crew member short. The airman in question, Corporal Allan Kosnar, "had asked to be excused from this exercise."[18] | |||

In popular culture

- The pulp magazine Argosy published an account of the incident in 1974.[5]

- The 1977 science fiction film Close Encounters of the Third Kind featured a depiction of the Flight 19 planes being discovered in the desert and later their pilots are returned to Earth by peaceful alien captors. In the film, the returned fliers are depicted at the age they would have been at the time of their disappearance, but have fictional names.

- In 1977, the English experimental rock band 801 wrote and recorded the song "Flight 19", with the chorus: "Saint Serene, get me on Flight 19".

- In 1978, the American rock band Blondie included the song "Bermuda Triangle Blues (Flight 45)" on their album "Plastic Letters". The lyrics include "Several hours out - 20 minutes south of Bermuda. The communication's gone - something has to be so wrong."

- In The Invincible Iron Man #504 (July 2011), Bethany Cabe finds a plane on the ocean floor while diving, a find she referred to as "Flight 19".[19]

- In 1980, Scottish singer/songwriter B. A. Robertson released a single, "Flight 19".

- In a chapter of a 1980 work of science fiction by Peter J. Hammond, Corporal Allan Kosnar, who had successfully asked to be excused from Flight 19,[18] has been said to have done so because he had had a strong premonition of danger.[20]

- The supporters group of the Fort Lauderdale Strikers is named after Flight 19.

References

- 1 2 3 Mayell, Hillary (December 15, 2003). "Bermuda Triangle: Behind the Intrigue". National Geographic. p. 2. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 McDonell, Michael (June 1973). "Lost Patrol" (PDF). Naval Aviation News: 8–16.

- 1 2 3 4 Naval Air Advanced Training Command Board of Inquiry (December 7, 1945). Board of Investigation Into 5 Missing TBM Airplanes and One PBM Airplane Convened by Naval Air Advanced Training Command, NAS Jacksonville, Florida 7 December 1945 and Related Correspondence (Flight 19) (Report). United States Navy via iBiblio.org. Retrieved March 8, 2008.

- 1 2 Goodridge, Elisabeth (November 17, 2005). "Flight 19 crew honored by House; disappearance began notion of Bermuda Triangle". Free New Mexican. Archived from the original on November 26, 2005.

- 1 2 "Mysteries of the Bermuda Triangle". Decoding the Past. Season 1. 2005. History Channel.

- ↑ "Background on Naval Aircraft Bureau (Serial) Numbers". Naval History & Heritage Command. 2007.

- ↑ http://www.nasflmuseum.com/flight-19.html

- ↑ "Bermuda Triangle". Naked Science. Season 1. 2004. National Geographic Channel.

- ↑ (via Google Book archive):Bloom, Minerva. "Naval Air Station Fort Lauderdale: A Catalyst for Growth". Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ↑ Naval military Library reports this aircraft was not part of Flight 19

- ↑ Tim Golden (June 5, 1991). "Mystery of Bermuda Triangle Remains One". New York Times. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

The undersea explorers who announced last month that they might have discovered five Navy planes that vanished mysteriously in 1945, laying a foundation for the myth of a craft-swallowing Caribbean twilight zone, said that on closer inspection, the planes they found turned out not to be those of the fabled 'Flight 19.' ... Mr. Hawkes said at a news conference that in four of the five cases, the tail numbers of the planes his team had found did not match those of the lost aircraft.

- 1 2 Adam Higginbotham (March 2012). "Graham Hawkes and the Race to the Bottom of the Sea". Men's Journal. p. 3. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

Hawkes has since changed his story. Now he says both he (because his investors didn't want to waste valuable time on an investigation) and the Pentagon (because they had more important things to worry about) had an interest in making the story go away. He admits that while he didn't find conclusive evidence that the planes were the same group that went missing in 1945, he consulted a statistician to establish the probability that they were not. "He said, 'You've got Flight 19,' " Hawkes says.

- 1 2 "Online Video Extract from 'The Bermuda Triangle: Beneath the Waves'". YouTube. 2004. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ↑ Indeed, as documented here in the Military Times Hall Of Valor, the pilot, George Swint, went on to become a decorated war hero flying torpedo bombers from the USS Enterprise (an aircraft carrier that eventually gave its name to the spaceship in Star Trek) in 1944 and the USS Lexington in 1945, receiving the Navy Cross for "extraordinary heroism" in 1944 and the DFC for "extraordinary achievement" in 1945.

- ↑ "The Bermuda Triangle: Beneath the Waves". BBC. 2004. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

Graham Hawkes is also able to reveal, by using a state-of-the-art submarine, how five wrecks mysteriously wound up 730 feet down in the heart of the Bermuda Triangle.

Broadcasts: First broadcast (BBC1): Sun 14 Mar 2004; BBC4:Sat 28 Dec 2013, Mon 6 Jan 2014, Tue 7 Jan 2014, Thu 6 Mar 2014, Fri 7 Mar 2014, Tue 9 Aug 2014, Wed 10 Aug 2014

Alternative name (and full credits) at IMDB: Dive to Bermuda Triangle (2004)

Quotes from a transcript of the text of a shortened version of the program (including advertisements):

...

00:24:22 It's much, much more untidy if it isn't flight 19 and we have to find out where they are.

00:24:30 Graham Hawkes is now going to return to the phantom five, and using a new submersible, he is going to go down there himself and find out, once and for all, who they are.

00:24:47 Graham has waited 12 years for this moment.

...

00:38:36 "Nav 23990-- " on the 9th october, 1943, ft-87, piloted by ensign george swint, was returning to fort lauderdale from a bombing run.

00:38:53 Onboard were airmen second class sam treese and j. lewulis.

00:38:59 , the engine suffered a catastrophic loss of fuel and ditched.

00:39:06 Swint and his crew survived.

00:39:10 Ft-87-- ..

00:39:20 Graham now knows how she got here.

00:39:23 Of the remaining four wrecks, graham could never definitively identify the downed avengers.

00:39:32 Despite the odds, they are just a random collection of accidents that came to rest in the same place 12 miles from home. ... - ↑ "Flight 19 Memorial". Naval Air Station Fort Lauderdale Museum. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

A sad but equally historic note is the fact that 95 young Americans lost their lives at the NAS Fort Lauderdale base during 1942-1945— the three most intensive training years of the war.

- ↑ Kaye, Ken (2 April 2015), "Were two dead pilots part of Lost Patrol?", Sun Sentinel, Fort Lauderdale, FL, retrieved 6 April 2015

- 1 2 "The Mystery of Flight 19". Naval Air Station Fort Lauderdale Museum. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

FT - 81: Pilot: 2nd Lt. Forrest J. Gerber, USMCR. Aircraft: TBM-1C. BuNo 46325. Crew: (Only one) Pfc. William Lightfoot, USMCR. That day, Corporal Allan Kosnar had asked to be excused from this exercise.

- ↑ Fraction, Matt (w), Larroca, Salvador (a). "Fear Itself Part 1: City Of Light, City Of Stone" The Invincible Iron Man (July 2011), Marvel Comics

- ↑ Hammond, Peter J. (1980). "The Bermuda Triangle". Sapphire & Steel Annual 1981. Manchester: World International Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-0723566014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Flight 19. |

- "The Loss Of Flight 19" by the Navy History and Heritage Command

- "The Mystery of Flight 19" by Naval Air Station Fort Lauderdale Museum

- "The Lost Patrol" a 1982 Flight article