Fishing industry

The fishing industry includes any industry or activity concerned with taking, culturing, processing, preserving, storing, transporting, marketing or selling fish or fish products. It is defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization as including recreational, subsistence and commercial fishing, and the harvesting, processing, and marketing sectors.[2] The commercial activity is aimed at the delivery of fish and other seafood products for human consumption or as input factors in other industrial processes. Directly or indirectly, the livelihood of over 500 million people in developing countries depends on fisheries and aquaculture.[3]

Sectors

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

There are three principal industry sectors:[4]

- The commercial sector: comprises enterprises and individuals associated with wild-catch or aquaculture resources and the various transformations of those resources into products for sale. It is also referred to as the "seafood industry", although non-food items such as pearls are included among its products.

- The traditional sector: comprises enterprises and individuals associated with fisheries resources from which aboriginal people derive products in accordance with their traditions.

- The recreational sector: comprises enterprises and individuals associated for the purpose of recreation, sport or sustenance with fisheries resources from which products are derived that are not for sale.

Commercial sector

The commercial sector of the fishing industry comprises the following chain:

- Commercial fishing and fish farming which produce the fish

- Fish processing which produce the fish products

- Marketing of the fish products

World production

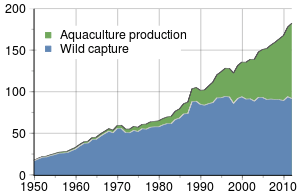

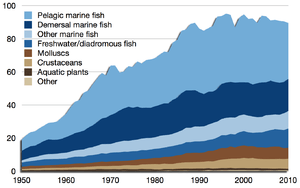

Fish are harvested by commercial fishing and aquaculture.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the world harvest in 2005 consisted of 93.3 million tonnes captured by commercial fishing in wild fisheries, plus 48.1 million tonnes produced by fish farms. In addition, 1.3 million tons of aquatic plants (seaweed etc.) were captured in wild fisheries and 14.8 million tons were produced by aquaculture.[5] The number of individual fish caught in the wild has been estimated at 0.97-2.7 trillion per year (not counting fish farms or marine invertebrates).[6]

Following is a table of the 2011 world fishing industry harvest in tonnes by capture and by aquaculture.[5]

| Capture (ton) | Aquaculture (ton) | Total (ton) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 94,574,113 | 83,729,313 | 178,303,426 |

| Aquatic plant | 1,085,143 | 20,975,361 | 22,060,504 |

| Aquatic animal | 93,488,970 | 62,753,952 | 156,202,922 |

Commercial fishing

The top producing countries were, in order, the People's Republic of China (excluding Hong Kong and Taiwan), Peru, Japan, the United States, Chile, Indonesia, Russia, India, Thailand, Norway and Iceland. Those countries accounted for more than half of the world's production; China alone accounted for a third of the world's production.

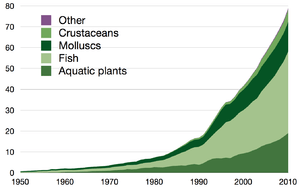

Fish farming

Aquaculture is the cultivation of aquatic organisms. Unlike fishing, aquaculture, also known as aquafarming, is the cultivation of aquatic populations under controlled conditions.[7] Mariculture refers to aquaculture practiced in marine environments. Particular kinds of aquaculture include algaculture (the production of kelp/seaweed and other algae); fish farming; shrimp farming, shellfish farming, and the growing of cultured pearls.

Fish farming involves raising fish commercially in tanks or enclosed pools, usually for food. Fish species raised by fish farms include carp, salmon, tilapia, catfish and cod. Increasing demands on wild fisheries by commercial fishing operations have caused widespread overfishing. Fish farming offers an alternative solution to the increasing market demand for fish and fish protein.

Fish processing

Fish processing is the processing of fish delivered by commercial fisheries and fish farms. The larger fish processing companies have their own fishing fleets and independent fisheries. The products of the industry are usually sold wholesale to grocery chains or to intermediaries.

Fish processing can be subdivided into two categories: fish handling (the initial processing of raw fish) and fish products manufacturing. Aspects of fish processing occur on fishing vessels, fish processing vessels, and at fish processing plants.

Another natural subdivision is into primary processing involved in the filleting and freezing of fresh fish for onward distribution to fresh fish retail and catering outlets, and the secondary processing that produces chilled, frozen and canned products for the retail and catering trades.[8]

Fish products

Fisheries are estimated to currently provide 16% of the world population's protein. The flesh of many fish are primarily valued as a source of food; there are many edible species of fish. Other marine life taken as food includes shellfish, crustaceans, sea cucumber, jellyfish and roe.

Fish and other marine life can also be used for many other uses: pearls and mother-of-pearl, sharkskin and rayskin. Sea horses, star fish, sea urchins and sea cucumber are used in traditional Chinese medicine. Tyrian purple is a pigment made from marine snails, sepia is a pigment made from the inky secretions of cuttlefish. Fish glue has long been valued for its use in all manner of products. Isinglass is used for the clarification of wine and beer. Fish emulsion is a fertilizer emulsion that is produced from the fluid remains of fish processed for fish oil and fish meal.

In the industry the term seafood products is often used instead of fish products.

Fish marketing

Fish markets are marketplace used for the trade in and sale of fish and other seafood. They can be dedicated to wholesale trade between fishermen and fish merchants, or to the sale of seafood to individual consumers, or to both. Retail fish markets, a type of wet market, often sell street food as well.

Most shrimp are sold frozen and are marketed in different categories.[9] The live food fish trade is a global system that links fishing communities with markets.

Traditional sector

The traditional fishing industry, or artisan fishing, are terms used to describe small scale commercial or subsistence fishing practises, particularly using traditional techniques such as rod and tackle, arrows and harpoons, throw nets and drag nets, etc. It does not usually cover the concept of fishing for sport, and might be used when talking about the pressures between large scale modern commercial fishing practises and traditional methods, or when aid programs are targeted specifically at fishing at or near subsistence levels.

Recreational sector

The recreational fishing industry consists of enterprises such as the manufacture and retailing of fishing tackle and apparel, the payment of license fees to regulatory authorities, fishing books and magazines, the design and building of recreational fishing boats, and the provision of accommodation, fishing boats for charter, and guided fishing adventures.

Lift nets in Cà Mau, Vietnam

Lift nets in Cà Mau, Vietnam Fly fishing in a river

Fly fishing in a river

International disputes

The ocean covers 71% of the earth's surface and 80% of the value of exploited marine resources are attributed to the fishing industry. The fishing industry has provoked various international disputes as wild fish capture rose to a peak about the turn of the century, and has since started a gradual decline.[10] Iceland, Japan, and Portugal are the greatest consumers of seafood per capita in the world.

Disputes in the Americas

Chile and Peru are countries with high fish consumption, and therefore had troubles regarding fish industry. In 1947, Chile and Peru first adopted the 200 nautical miles of Exclusive Economic Zone for their shore, and in 1982, UN formally adopted this term. In the 2000s, Chile and Peru suffered serious fish crisis because of excessive fishing and lack of proper regulations, and now political power play in the area is rekindled.[11] From the late 1950s, offshore bottom trawlers began exploiting the deeper part, leading to a large catch increase and a strong decline in the underlying biomass. The stock collapsed to extremely low levels in the early 1990s and this is a well-known example of non-excludable, non-rivalrous public good in economics, causing free-rider problems.

Disputes in Europe

Iceland is one of the largest consumers in the world and in 1972, a dispute occurred between UK and Iceland because of Iceland’s announcement of Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) to reduce overfishing. This dispute is called the Cod War, direct confrontations between Icelandic patrol vessels and British warships. Nowadays in Europe in general, countries are searching for a way to recover fishing industry. Overfishing of EU fisheries is costing 3.2 billion euros a year and 100,000 jobs according to a report. So Europe is constantly looking for some collective actions to prevent overfishing.[12]

Disputes in Asia

Japan, China and Korea are some of the greatest consumers of fish, and have some disputes over Exclusive Economic Zone. In 2011, due to a serious earthquake, the nuclear power facility in Fukushima was damaged. Ever since, huge amount of contaminated water leaked and is entering the oceans. Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco) admitted that around 300 tonnes of highly radioactive water had leaked from a storage tank on the site. In the Kuroshio Current, the sea near Fukushima, about 11 countries catch fish. Not only the surrounding countries such as Japan, Korea and China, but also the countries like Ukraine, Spain and Russia have boats in the Kuroshio Current. In September 2013, South Korea banned all fish imports from eight Japanese prefectures, concerning radioactive water leak from the Fukushima nuclear plant.[12]

See also

References

- 1 2 Based on data sourced from the FishStat database Archived November 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ FAO Fisheries Section: Glossary: Fishing industry. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- ↑ Fisheries and Aquaculture in our Changing Climate Policy brief of the FAO for the UNFCCC COP-15 in Copenhagen, December 2009.

- ↑ The wording of the following definitions of the fishing industry are based on those used by the Australian government

- 1 2 "FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture - Home". Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ↑ A Mood and P Brooke (July 2010). Estimating the Number of Fish Caught in Global Fishing Each Year. FishCount.org.uk.

- ↑ "Answers - The Most Trusted Place for Answering Life's Questions". Answers.com. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ↑ Royal Society of Edinburgh (2004) Inquiry into the future of the Scottish fishing industry. 128pp.

- ↑ "Comparative economics of shrimp farming in Asia". Aquaculture. 164: 183–200. doi:10.1016/s0044-8486(98)00186-0.

- ↑ Millennium Ecosystem Assessment

- ↑ "In Mackerel's Plunder, Hints of Epic Fish Collapse". International Herald Tribune. 25 January 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2016 – via The New York Times.

- 1 2 "Overfishing 'costs EU £2.7bn each year'". BBC News. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

External links

- FAO Fisheries Information

- World Fishing Today, news from fishing industry

- Fish database (FishBase)

- American Fisheries Society

- NOAA Fisheries Service

- One Fish

- The Sunken Billions: The Economic Justification for Fisheries Reform

.png)