Fireside chats

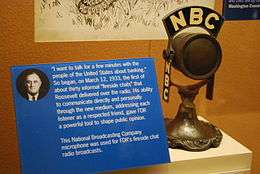

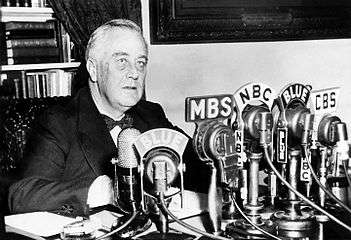

President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered his first fireside chat, on the banking crisis, eight days after taking office (March 12, 1933) | |

| Duration | 13–44 minutes |

|---|---|

| Date | March 12, 1933 – June 12, 1944 |

| Type | 30 Presidential radio addresses |

| Participants | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

The series of fireside chats was among the first 50 recordings made part of the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress, which noted it as "an influential series of radio broadcasts in which Roosevelt utilized the media to present his programs and ideas directly to the public and thereby redefined the relationship between the President and the American people."

Origin

It cannot misrepresent or misquote. It is far reaching and simultaneous in releasing messages given it for transmission to the nation or for international consumption.

Roosevelt understood that his administration's success depended upon a favorable dialogue with the electorate — possible only through methods of mass communication — and that the true power of the presidency was the ability to take the initiative. The use of radio for direct appeals was perhaps the most important of FDR's innovations in political communication.[1]:153 Roosevelt's opponents had control of most newspapers in the 1930s and press reports were under their control and involved their editorial commentary. Historian Betty Houchin Winfield says, "He and his advisers worried that newspapers' biases would affect the news columns and rightly so."[2] Historian Douglas B. Craig says that he "offered voters a chance to receive information unadulterated by newspaper proprietors' bias" through the new medium of radio.[3]

Roosevelt first used what would become known as fireside chats in 1929 as Governor of New York.[4] He faced a conservative Republican legislature, so during each legislative session he would occasionally address the residents of New York directly.[5] His third gubernatorial address—April 3, 1929, on WGY radio—is cited by Roosevelt biographer Frank Freidel as being the first fireside chat.[5]

In these speeches, Roosevelt appealed to radio listeners for help getting his agenda passed.[4] Letters would pour in following each of these addresses, which helped pressure legislators to pass measures Roosevelt had proposed.[6]

|

Fireside Chat 1 On the Banking Crisis

Roosevelt's first Fireside Chat on the Banking Crisis (March 12, 1933) |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

As President, Roosevelt began making the informal addresses on March 12, 1933, eight days after his inauguration. He had spent his first week coping with a month-long epidemic of bank closings that was ruining families nationwide.[7]:78 He closed the entire American banking system on March 6. On March 9 Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act, which Roosevelt used to effectively create federal deposit insurance when the banks reopened.[8] At 10 p.m. ET that Sunday night, on the eve of the end of the bank holiday, Roosevelt spoke to a radio audience of more than 60 million people, to tell them in clear language "what has been done in the last few days, why it was done, and what the next steps are going to be".[7]:78–79

The result, according to economic historian William L. Silber, was a "remarkable turnaround in the public's confidence ... The contemporary press confirms that the public recognized the implicit guarantee and, as a result, believed that the reopened banks would be safe, as the President explained in his first Fireside Chat." Within two weeks people returned more than half of the cash they had been hoarding, and the first stock-trading day after the bank holiday marked the largest-ever one-day percentage price increase.[8]

The term "fireside chat" was inspired by a statement by Roosevelt's press secretary, Stephen Early, who said that the president liked to think of the audience as a few people seated around his fireside. Listeners were able to picture FDR in his study, in front of the fireplace, and could imagine they were sitting beside him.[9]:57–58 The term was coined by CBS broadcast executive Harry C. Butcher of the network's Washington, D.C., office,[10] in a press release before the address of May 7, 1933.[11] The phrase has often been credited to CBS journalist Robert Trout, but he said he was simply the first person to use the it on the air.[12] The title was picked up by the press and public and later used by Roosevelt himself,[11] becoming part of American folklore.[10]

Presentation

It is whispered by some that only by abandoning our freedom, our ideals, our way of life, can we build our defenses adequately, can we match the strength of the aggressors. ... I do not share these fears.

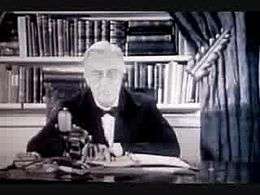

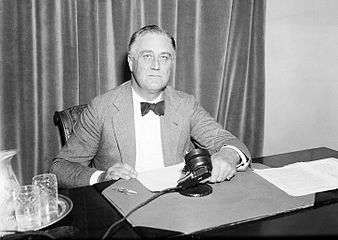

Roosevelt customarily made his address from the Diplomatic Reception Room of the White House. He would arrive 15 minutes before air time to welcome members of the press, including radio and newsreel correspondents. NBC White House announcer Carleton E. Smith gave him a simple introduction: "Ladies and gentlemen, the President of the United States." Roosevelt most often began his talks with the words, "My friends" or "My fellow Americans", and he read his speech from a looseleaf binder.[10] Presidential advisor and speechwriter Samuel Rosenman recalled his use of common analogies and his care in avoiding dramatic oratory: "He looked for words that he would use in an informal conversation with one or two of his friends".[9]:58 Eighty percent of the words used were in the thousand most commonly used words in the English language.[6]

The radio historian John Dunning wrote that "It was the first time in history that a large segment of the population could listen directly to a chief executive, and the chats are often credited with helping keep Roosevelt's popularity high."[10]

Each radio address went through about a dozen drafts. Careful attention was also given to Roosevelt's delivery. When he realized that a slight whistle was audible on the air due to a separation between his two front lower teeth, FDR had a removable bridge made.[9]:58

FDR is regarded as one of the most effective communicators in radio history.[10] Although the fireside chats are sometimes thought of as weekly events, Roosevelt delivered just 30 addresses[6] during a presidency lasting 4,422 days.[14] He resisted those who encouraged him to speak on radio more frequently, as shown in his response to Russell Leffingwell after the address of February 23, 1942:

The one thing I dread is that my talks should be so frequent as to lose their effectiveness. ... Every time I talk over the air it means four or five days of long, overtime work in the preparation of what I say. Actually, I cannot afford to take this time away from more vital things. I think we must avoid too much personal leadership—my good friend Winston Churchill has suffered a little from this.[9]:319–320

Gallery

-

Fireside chat on the merits of the recovery program (June 28, 1934)

-

Fireside chat on government and capitalism (September 30, 1934)

-

Fireside chat on the WPA and the Social Security Act (April 28, 1935)

-

Fireside chat on drought conditions and labor (September 6, 1936)

-

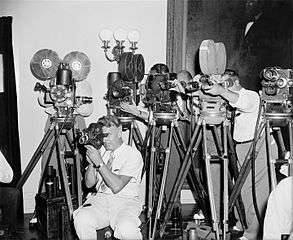

Radio press at fireside chat (September 3, 1939)

-

Newsreel cameras at fireside chat (September 3, 1939)

-

Fireside chat on maintaining freedom of the seas (September 11, 1941). The black arm band signifies his mourning the death of his mother, Sara Delano Roosevelt.

-

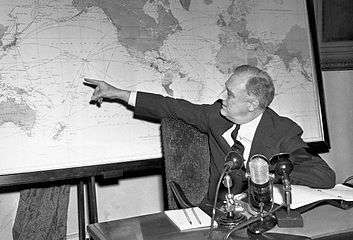

Fireside chat on the progress of the war (February 23, 1942)

-

Fireside chat on the Tehran Conference and Cairo Conference (December 24, 1943)[1]

-

Fireside chat on the State of the Union (January 11, 1944)[2]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

FC_27was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

FC_28was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Chronological list of addresses

| # | Date | Topic | Length | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sunday, March 12, 1933 | On the Banking Crisis[15] | 13:42[16] | Audio, transcript |

| 2 | Sunday, May 7, 1933 | Outlining the New Deal Program[17] | 22:42[16] | Audio, Transcript |

| 3 | Monday, July 24, 1933 | On the National Recovery Administration[18] | not recorded[16] | Transcript |

| 4 | Sunday, October 22, 1933 | On Economic Progress[19] | not recorded[16] | Transcript |

| 5 | Thursday, June 28, 1934 | Achievements of the 73rd U.S. Congress and Critics of the New Deal[20] | not recorded[16] | Transcript |

| 6 | Sunday, September 30, 1934 | On Government and Capitalism[21] | 27:20[16] | Audio, Transcript |

| 7 | Sunday, April 28, 1935 | On the Works Relief Program and the Social Security Act[22] | 28:08[16] | Audio (excerpt), Transcript |

| 8 | Sunday, September 6, 1936 | On Drought Conditions, Farmers and Laborers[23] | 26:49[16] | Audio, Transcript |

| 9 | Tuesday, March 9, 1937 | On the Reorganization of the Judiciary[24] | 35:28[16] | Audio, transcript |

| 10 | Tuesday, October 12, 1937 | On New Legislation to be Recommended to Congress[25] | 27:42[16] | Transcript |

| 11 | Sunday, November 14, 1937 | On the Unemployment Census[26] | 14:16[16] | Transcript |

| 12 | Thursday, April 14, 1938 | On the Recession[27] | 40:42[16] | Transcript |

| 13 | Friday, June 24, 1938 | On Party Primaries[28] | 29:02[16] | Audio, Transcript |

| 14 | Sunday, September 3, 1939 | On the European War[29] | 11:25[16] | Audio excerpt, Transcript |

| 15 | Sunday, May 26, 1940 | On National Defense[30] | 31:32[16] | Audio, Transcript |

| 16 | Sunday, December 29, 1940 | On the "Arsenal of Democracy"[31] | 36:53[16] | Audio, Transcript |

| 17 | Tuesday, May 27, 1941 | Announcing Unlimited National Emergency[32] | 44:27[16] | Transcript |

| 18 | Thursday, September 11, 1941 | On Maintaining Freedom of the Seas and the Greer Incident[33] | 28:33[16] | Audio, Transcript |

| 19 | Tuesday, December 9, 1941 | On the Declaration of War with Japan[34] | 26:19[16] | Audio, Transcript |

| 20 | Monday, February 23, 1942 | On the Progress of the War[35] | 36:34[16] | Audio, Transcript |

| 21 | Tuesday, April 28, 1942 | On Our National Economic Policy and Sacrifice[36] | 32:42[16] | Audio, Transcript |

| 22 | Monday, September 7, 1942 | On Inflation and Progress of the War[37] | 26:56[16] | Audio, Transcript |

| 23 | Monday, October 12, 1942 | Report on the Home Front[38] | 29:25[16] | Transcript |

| 24 | Sunday, May 2, 1943 | On the Coal Crisis[39] | 21:06[16] | Audio, Transcript |

| 25 | Wednesday, July 28, 1943 | On the Fall of Mussolini[40] | 29:11[16] | Audio, Transcript |

| 26 | Wednesday, September 8, 1943 | On the Armistice with Italy and the Third War Loan Drive[41] | 12:38[16] | Transcript |

| 27 | Friday, December 24, 1943 | On the Tehran and Cairo Conferences[42] | 28:29[16] | Audio, Transcript |

| 28 | Tuesday, January 11, 1944 | On the State of the Union[13] | 30:20[16] | Transcript |

| 29 | Monday, June 5, 1944 | On the Fall of Rome[43] | 14:36[16] | Transcript |

| 30 | Monday, June 12, 1944 | Opening the Fifth War Loan Drive[44] | 13:02[16] | Transcript |

Reception

2232. 78th Street Brooklyn, N.Y.

March 13th 1933.

Secretary to the President

The White House

Washington. D.C.

Dear Sir: Being a citizen of little or no consequence I feel the utter futility of writing to the President at a time such as this, but I trust you will accept this letter in the spirit in which it was written. For me to sit down to write to any public official, whoever he may be, it must be prompted by a very special and appealing occasion or personality. That happened last evening, as I listened to the President's broadcast. I feel that he walked into my home, sat down and in plain and forceful language explained to me how he was tackling the job I and my fellow citizens gave him. I thought what splendid thing it would be if he could find time to do that occasionally. Needless to say, such forceful direct and honest action commands the respect of all Americans, it is certainly deserving of it. My humble and sincere gratitude to a great leader. May God protect him.

Respectfully

J.F. BandoRoosevelt's radio audiences averaged 18 percent during peacetime, and 58 percent during the war.[45] The fireside chats attracted more listeners than the most popular radio shows, which were heard by 30–35 percent of the radio audience. Roosevelt's fireside chat of December 29, 1940, was heard by 59 percent of radio listeners. His address of May 27, 1941, was heard by 70 percent of the radio audience.[9]:240 An estimated 62,100,000 people heard Roosevelt's fireside chat December 9, 1941—attaining a Hooper rating of 79, the record high for a Presidential address.[46]

Approximately 61,365,000 adults tuned in February 23, 1942, for FDR's first fireside chat since the attack on Pearl Harbor, in which he outlined the principal purposes of the war.[46] In advance of the address Roosevelt asked citizens to have a world map in front of them as they listened to him speak. "I'm going to speak about strange places that many of them never heard of—places that are now the battleground for civilization," he told his speechwriters. "I want to explain to the people something about geography—what our problem is and what the overall strategy of the war has to be. … If they understand the problem and what we are driving at, I am sure that they can take any kind of bad news right on the chin." Sales of new maps and atlases were unprecedented, while many people retrieved old commercial maps from storage and pinned them up on their walls.[9]:319 The New York Times called the speech "one of the greatest of Roosevelt's career".[9]:320

Novelist Saul Bellow recalled hearing a fireside chat while walking in Chicago one summer evening. "The blight hadn't yet carried off the elms, and under them drivers had pulled over, parking bumper to bumper, and turned on their radios to hear Roosevelt. They had rolled down the windows and opened the car doors. Everywhere the same voice, its odd Eastern accent, which in anyone else would have irritated Midwesterners. You could follow without missing a single word as you strolled by. You felt joined to these unknown drivers, men and women smoking their cigarettes in silence, not so much considering the President's words as affirming the rightness of his tone and taking assurance from it."[9]:450–451[47]

This level of intimacy with politics made people feel as if they too were part of the administration's decision-making process and many soon felt that they knew Roosevelt personally. Most importantly, they grew to trust him. The conventional press grew to love Roosevelt because they too had gained unprecedented access to the goings-on of government.[48]

Legacy

Every U.S. president since Roosevelt has delivered periodic addresses to the American people, first on radio, and later adding television and the Internet. The practice of regularly scheduled addresses began in 1982 when President Ronald Reagan started delivering a radio broadcast every Saturday.[49]

Accolades

The series of Roosevelt's 30 fireside chats was included with the first 50 recordings made part of the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress. It is noted as "an influential series of radio broadcasts in which Roosevelt utilized the media to present his programs and ideas directly to the public and thereby redefined the relationship between the President and the American people."[50]

Further reading

- Craig, Douglas B. Fireside Politics: Radio and Political Culture in the United States, 1920-1940. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000. ISBN 9780801883125

- Foster, Tiara Kay. "Constructing a World War II America: The Rhetorical Craftsmanship of Franklin D. Roosevelt". PhD Dissertation. Syracuse University, 2013.[51]

- Hayes, Joy Elizabeth. 2000. "Did Herbert Hoover Broadcast the First Fireside Chat? Rethinking the Origins of Roosevelt's Radio Genius". Journal of Radio Studies. 7, no. 1: 76–92. ISSN 1095-5046

- Kiewe, Amos. FDR's First Fireside Chat: Public Confidence and the Banking Crisis. College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 2007. ISBN 9781585445974

- Lenthall, Bruce. Radio's America: The Great Depression and the Rise of Modern Mass Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007. ISBN 9780226471921

- Levine, Lawrence W., and Cornelia R. Levine. The Fireside Conversations: America Responds to FDR During the Great Depression. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010. ISBN 9780520265547

- Lim, Elvin T. 2003. "The Lion and the Lamb: De-mythologizing Franklin Roosevelt's Fireside Chats." Rhetoric & Public Affairs 6#3 (2003): 437–464. ISSN 1094-8392

- Ryan, Halford Ross. Franklin D. Roosevelt's Rhetorical Presidency. New York: Greenwood Press, 1988. ISBN 9780313255670

- Ryfe, David Michael. 2001. "From media audience to media public: a study of letters written in reaction to FDR's fireside chats." Media, culture & society 23#6 (2001): 767-781.

- Ryfe, David Michael. 1999. "Franklin Roosevelt and the fireside chats." Journal of communication 49#4 (1999): 80-103. ISSN 0021-9916

- Winfield, Betty Houchin. FDR and the News Media. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990. ISBN 9780252016721

References

- 1 2 Reedy, George E. (Winter 1992). "The First Great Communicator (book review, FDR and the News Media by Betty Houchin Winfield)". The Review of Politics. University of Notre Dame. 54 (1): 152–155. doi:10.1017/s003467050001723x.

- ↑ Betty Houchin Winfield (1994). FDR and the News Media. Columbia University Press. p. 146.

- ↑ Douglas B. Craig (2005). Fireside Politics: Radio and Political Culture in the United States, 1920-1940. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 156.

- 1 2 Burns, James MacGregor (1996). Roosevelt : the lion and the fox. New York, NY: Smithmark. p. 118. ISBN 978-0831756116.

- 1 2 Storm, Geoffrey (Spring 2007). "Roosevelt and WGY: The Origins of the Fireside Chats". New York History: Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association. New York State Historical Association. 88 (2): 183–85 (177–197). ISSN 0146-437X. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 Mankowski, Diana, and Raissa Jose (12 March 2003). "The 70th Anniversary of Roosevelt's Fireside Chats". Chicago: The Museum of Broadcast Communications. Archived from the original on May 17, 2012. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- 1 2 "FDR's First Fireside Chat". Radio Digest. 1 (1): 78–82. February 1939.

- 1 2 Silber, William L. (July 2009). "Why Did FDR's Bank Holiday Succeed?". Economic Policy Review. Federal Reserve Bank of New York. 15 (1). Retrieved 2015-10-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Goodwin, Doris Kearns (1995). No Ordinary Time. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780684804484.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 495. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3.

- 1 2 Buhite, Russell D, and David W Levy (1992). "Introduction". In Russell D Buhite and David W Levy, eds. Roosevelt's fireside chats (1st ed.). Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. xv. ISBN 9780806123707. Viewed 2 January 2013.

- ↑ Unger, Arthur (January 29, 1982). "Bob Trout's Roosevelt Days". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- 1 2 Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 28: On the State of the Union (January 11, 1944)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Skeens, Barbara Seuling ; illustrated by Matthew (2008). One president was born on Independence Day : and other freaky facts about the 26th through 43rd presidents. Minneapolis: Picture Window Books. p. 14. ISBN 9781404841185. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "FDR Fireside Chat 1: On the Banking Crisis (March 12, 1933)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 "Fireside Chats of Franklin D. Roosevelt". Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "FDR Fireside Chat 2: On Progress During the First Two Months (May 7, 1933)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 3: On the National Recovery Administration (July 24, 1933)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 4: On Economic Progress (October 22, 1933)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 5: On Addressing the Critics (June 28, 1934)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "FDR Fireside Chat 6: On Government and Capitalism (September 30, 1934)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 7: On the Works Relief Program and Social Security Act (April 28, 1935)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 8: On Farmers and Laborers (September 6, 1936)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 9: On 'Court-Packing' (March 9, 1937)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 10: On New Legislation (October 12, 1937)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 11: On the Unemployment Census (November 14, 1937)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 12: On the Recession (April 14, 1938)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 13: On Purging the Democratic Party (June 24, 1938)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 14: On the European War (September 3, 1939)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 15: On National Defense (May 26, 1940)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 16: On the 'Arsenal of Democracy' (December 29, 1940)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 17: On An Unlimited National Emergency (May 27, 1941)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 18: On The Greer Incident (September 11, 1941)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 19: On the War with Japan (December 9, 1941)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 20: On the Progress of the War (February 23, 1942)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 21: On Sacrifice (April 28, 1942)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 22: On Inflation and Food Prices (September 7, 1942)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 23: On the Home Front (October 12, 1942)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 24: On the Coal Crisis (May 2, 1943)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 25: On the Fall of Mussolini (July 28, 1943)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 26: On the Armistice in Italy (September 8, 1943)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 27: On the Tehran and Cairo Conferences (December 24, 1943)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 29: On the Fall of Rome (June 5, 1944)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat 30: Opening Fifth War Loan Drive (June 12, 1944)". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Douglas B. Craig (2005). Fireside Politics: Radio and Political Culture in the United States, 1920-1940. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 156.

- 1 2 "CBS Says 25,217,000 Heard Truman Friday". The New York Times. May 26, 1946. Retrieved 2015-09-16.

- ↑ Amis, Martin (April 27, 2015). "'There Is Simply Too Much to Think About,' Saul Bellow's Nonfiction". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-09-16.

- ↑ Lumeng (Jenny) Yu. The Great Communicator: How Roosevelt's Radio Speeches Shaped American History, pp. 89-106.

- ↑ "Reagan signs off with 331st weekly radio address". Deseret News. Associated Press. 1989-01-15. p. A3. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- ↑ "2002 Recording Registry". National Recording Preservation Board, Library of Congress. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- ↑ Foster, Tiara Kay (2013). "Constructing a World War II America: The Rhetorical Craftsmanship of Franklin D. Roosevelt" (PDF). College of Visual and Performing Arts, Syracuse University. Retrieved 2015-09-16.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- The New Deal Network from the Roosevelt Institute

- The Real Deal: Media and the Battle to Define Roosevelt's Social Programs at the University of Virginia: audio with editorial and cartoon reactions.

- Vincent Voice Library at Michigan State University, with many Roosevelt speeches in MP3 format