Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | |

|---|---|

|

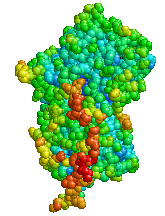

Structure of Alpha 1-antitrypsin | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology, medical genetics |

| ICD-10 | E88.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 273.4 |

| OMIM | 107400 |

| DiseasesDB | 434 |

| MedlinePlus | 000120 |

| eMedicine | med/108 |

| Patient UK | Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency |

| MeSH | D019896 |

| GeneReviews | |

Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency (α1-antitrypsin deficiency, A1AD) is a genetic disorder that causes defective production of alpha 1-antitrypsin (A1AT), leading to decreased A1AT activity in the blood and lungs, and deposition of excessive abnormal A1AT protein in liver cells.[1][2] There are several forms and degrees of deficiency; the form and degree depend on whether the sufferer has one or two copies of a defective allele. In the literature it has been described as either a recessive or co-dominant trait as there is some evidence that smoking heterozygotes are affected.[3] Severe A1AT deficiency causes panacinar emphysema or COPD in adult life in many people with the condition (especially if they are exposed to cigarette smoke).[4] The disorder can lead to various liver diseases in a minority of children and adults, and occasionally more unusual problems.[4] It is treated through avoidance of damaging inhalants and, in severe cases, by intravenous infusions of the A1AT protein or by transplantation of the liver or lungs. It usually produces some degree of disability and reduces life expectancy.[1]

Signs and symptoms

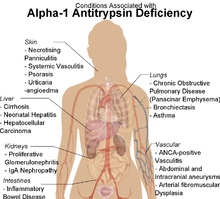

Symptoms of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency include shortness of breath, wheezing, rhonchi, and rales. The patient's symptoms may resemble recurrent respiratory infections or asthma that does not respond to treatment. Individuals with A1AD may develop emphysema during their thirties or forties even without a history of significant smoking, though smoking greatly increases the risk for emphysema.[1] A1AD causes impaired liver function in some patients and may lead to cirrhosis and liver failure (15%). In newborns, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency has indicators that include early onset jaundice followed by prolonged jaundice. It is a leading indication for liver transplantation in newborns.

Associated conditions

α1-antitrypsin deficiency has been associated with a number of diseases:

- Cirrhosis

- COPD

- Pneumothorax

- Asthma

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Pancreatitis

- Gallstones

- Bronchiectasis

- Pelvic organ prolapse[5]

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Emphysema, predominantly involving the lower lobes and causing bullae

- Secondary Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis

- Cancer

Pathophysiology

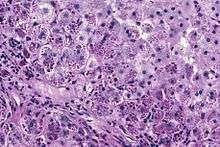

Alpha 1-antitrypsin (A1AT) is produced in the liver, and one of its functions is to protect the lungs from neutrophil elastase, an enzyme that can disrupt connective tissue.[1] Normal blood levels of alpha-1 antitrypsin may vary with analytical method but are typically around 1.0-2.7 g/l.[6] In individuals with PiSS, PiMZ and PiSZ genotypes, blood levels of A1AT are reduced to between 40 and 60% of normal levels. This is usually sufficient to protect the lungs from the effects of elastase in people who do not smoke. However, in individuals with the PiZZ genotype, A1AT levels are less than 15% of normal, and patients are likely to develop panacinar emphysema at a young age; 50% of these patients will develop liver cirrhosis, because the A1AT is not secreted properly and therefore accumulates in the liver . A liver biopsy in such cases will reveal PAS-positive, diastase-resistant granules. Unlike glycogen and other mucins which are diastase sensitive (i.e., diastase treatment disables PAS staining), A1AT deficient hepatocytes will stain with PAS even after diastase treatment - a state thus referred to as diastase resistant.

Cigarette smoke is especially harmful to individuals with A1AD.[1] In addition to increasing the inflammatory reaction in the airways, cigarette smoke directly inactivates alpha 1-antitrypsin by oxidizing essential methionine residues to sulfoxide forms, decreasing the enzyme activity by a factor of 2000.

Genetics

Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade A, member 1 (SERPINA1) is the gene that encodes the protein Alpha 1-antitrypsin. SERPINA1 has been localized to chromosome 14q32. Over 75 mutations of the SERPINA1 gene have been identified, many with clinically significant effects.[7] The most common cause of severe deficiency is a single base-pair substitution leading to a glutamate to lysine mutation at position 342 (dbSNP: rs28929474), while PiS is caused by a glutamate to valine mutation at position 264 (dbSNP: rs17580). Other rarer forms have been described (see OMIM).

Diagnosis

A1AT deficiency remains undiagnosed in many patients. Patients are usually labelled as having COPD without an underlying cause. It is estimated that about 1% of all COPD patients actually have A1AT deficiency. Thus, testing should be performed for all patients with COPD, asthma with irreversible air-flow obstruction, unexplained liver disease, or necrotizing panniculitis. The initial test performed is serum A1AT level. A low level of A1AT confirms the diagnosis and further assessment with A1AT protein phenotyping and A1AT genotyping should be carried out subsequently.[8] The Alpha-1 Foundation offers free, confidential testing.

As protein electrophoresis does not completely distinguish between A1AT and other minor proteins at the alpha-1 position (agarose gel), antitrypsin can be more directly and specifically measured using a nephelometric or immunoturbidimetric method. Thus, protein electrophoresis is useful for screening and identifying individuals likely to have a deficiency. A1AT is further analysed by isoelectric focusing (IEF) in the pH range 4.5-5.5, where the protein migrates in a gel according to its isoelectric point or charge in a pH gradient. Normal A1AT is termed M, as it is migrates toward the center of such an IEF gel. Other variants are less functional, and are termed A-L and N-Z, dependent on whether they run proximal or distal to the M band. The presence of deviant bands on IEF can signify the presence of alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Since the number of identified mutations has exceeded the number of letters in the alphabet, subscripts have been added to most recent discoveries in this area, as in the Pittsburgh mutation described above. As every person has two copies of the A1AT gene, a heterozygote with two different copies of the gene may have two different bands showing on electrofocusing, although a heterozygote with one null mutant that abolishes expression of the gene will only show one band. In blood test results, the IEF results are notated as, e.g., PiMM, where Pi stands for protease inhibitor and "MM" is the banding pattern of that person.

Other detection methods include use of enzyme-linked-immuno-sorbent-assays in vitro and radial immunodiffusion. Alpha 1-antitrypsin levels in the blood depend on the genotype. Some mutant forms fail to fold properly and are, thus, targeted for destruction in the proteasome, whereas others have a tendency to polymerise, thereafter being retained in the endoplasmic reticulum. The serum levels of some of the common genotypes are:

- PiMM: 100% (normal)

- PiMS: 80% of normal serum level of A1AT

- PiSS: 60% of normal serum level of A1AT

- PiMZ: 60% of normal serum level of A1AT

- PiSZ: 40% of normal serum level of A1AT

- PiZZ: 10-15% (severe alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency)

Treatment

In the United States, Canada, and several European countries, lung-affected A1AD patients may receive intravenous infusions of alpha-1 antitrypsin, derived from donated human plasma. This augmentation therapy is thought to arrest the course of the disease and halt any further damage to the lungs. Long-term studies of the effectiveness of A1AT replacement therapy are not available. It is currently recommended that patients begin augmentation therapy only after the onset of emphysema symptoms.[8]

To date (April 2015) there are four IV augmentation therapy manufacturers in the United States, Canada and several European countries. Intravenous (IV) therapies are the standard mode of augmentation therapy delivery. Researchers are exploring inhaled therapies. IV Augmentation therapy is manufactured by the following companies and have been shown to be clinically identical to one another in terms of dosage and efficacy.

- Grifols

- CSL-Behring

- Kamada Ltd.

- Shire

Augmentation therapy is not appropriate for liver-affected patients; treatment of A1AD-related liver damage focuses on alleviating the symptoms of the disease. In severe cases, liver transplantation may be necessary.

As α1-antitrypsin is an acute phase reactant, its transcription is markedly increased during inflammation elsewhere in response to increased interleukin-1 and 6 and TNFα production.

Treatments currently being studied include recombinant and inhaled forms of A1AT. Other experimental therapies are aimed at the prevention of polymer formation in the liver.[9] In addition, significant strides have been made in improving the survival of individuals affected with Alpha-1 through AlphaNet's Alpha-1 Disease Management Program, a unique and innovative disease management program. The results of this program were first documented in the Effects of a Disease Management Program in Individuals with Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency.[10]

Epidemiology

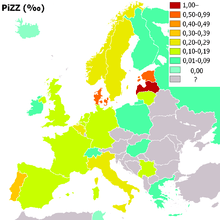

People of northern European, Iberian ancestry are at the highest risk for A1AD. Four percent carry the PiZ allele; between 1 in 625 and 1 in 2000 are homozygous.

Another study detected a frequency of 1 in 1550 individuals and a gene frequency of 0.026. The highest prevalence of the PiZZ variant was recorded in the northern and western European countries with mean gene frequency of 0.0140.[11]

Patient Registry

Lung-affected A1AD patients, families, and caregivers are encouraged to join the Alpha 1 Foundation Research Registry . They can also join NIH Rare Lung Diseases Consortium Contact Registry. This is a privacy protected site that provides up-to-date information for individuals interested in the latest scientific news, trials, and treatments related to rare lung diseases.

History

A1AD was discovered in 1963 by Carl-Bertil Laurell (1919–2001), at the University of Lund in Sweden.[12] Laurell, along with a medical resident, Sten Eriksson, made the discovery after noting the absence of the α1 band on protein electrophoresis in five of 1500 samples; three of the five patient samples were found to have developed emphysema at a young age.

The link with liver disease was made six years later, when Harvey Sharp et al. described A1AD in the context of liver disease.[13]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, eds. (2005). Robbins and Cotran Pathological Basis of Disease (7th ed.). Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 911–2. ISBN 0-7216-0187-1.

- ↑ Stoller J, Aboussouan L (2005). "Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency". Lancet. 365 (9478): 2225–36. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66781-5. PMID 15978931.

- ↑ Marciniuk, DD; Hernandez, P; Balter, M; Bourbeau, J; Chapman, KR; Ford, GT; Lauzon, JL; Maltais, F; O'Donnell, DE; Goodridge, D; Strange, C; Cave, AJ; Curren, K; Muthuri, S; Canadian Thoracic Society COPD Clinical Assembly Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency Expert Working, Group (NaN). "Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency targeted testing and augmentation therapy: a Canadian Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline.". Canadian Respiratory Journal. 19 (2): 109–16. doi:10.1155/2012/920918. PMC 3373286

. PMID 22536580. Check date values in:

. PMID 22536580. Check date values in: |date=(help) - 1 2 Needham M, Stockley RA (2004). "α1-Antitrypsin deficiency • 3: Clinical manifestations and natural history". Thorax. 59 (5): 441–5. doi:10.1136/thx.2003.006510. PMC 1746985

. PMID 15115878.

. PMID 15115878. - ↑ Chen B, Wen Y, Polan ML (2004). "Elastolytic activity in women with stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse". Neurourol. Urodyn. 23 (2): 119–26. doi:10.1002/nau.20012. PMID 14983422.

- ↑ Donato, Leslie; Jenkins; et al. (2012). "Reference and Interpretive Ranges for α1-Antitrypsin Quantitation by Phenotype in Adult and Pediatric Populations". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 138 (3): 398–405. doi:10.1309/AJCPMEEJK32ACYFP. PMID 22912357. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ↑ Silverman, Edwin K.; Sandhaus, Robert A. (2009-06-25). "Alpha1-Antitrypsin Deficiency". New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (26): 2749–2757. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0900449. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 19553648.

- 1 2 Silverman EK, Sandhaus RA (2009). "Alpha1-Antitrypsin Deficiency". New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (26): 2749–2757. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0900449. PMID 19553648.

- ↑ Mohanka M, Khemasuwan D, Stoller JK (June 2012). "A review of augmentation therapy for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency". Expert Opin Biol Ther. 12 (6): 685–700. doi:10.1517/14712598.2012.676638. PMID 22500781.

- ↑ Campos, Michael A.; Alazemi, Saleh; Zhang, Guoyan; Wanner, Adam; Sandhaus, Robert A. (2009-02-01). "Effects of a disease management program in individuals with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency". COPD. 6 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1080/15412550802607410. ISSN 1541-2563. PMID 19229706.

- ↑ Luisetti, M; Seersholm, N (February 2004). "Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. 1: epidemiology of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency.". Thorax. 59 (2): 164–9. doi:10.1136/thorax.2003.006494. PMC 1746939

. PMID 14760160.

. PMID 14760160. - ↑ Laurell CB, Eriksson S (1963). "The electrophoretic alpha 1-globulin pattern of serum in alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency". Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 15 (2): 132–140. doi:10.1080/00365516309051324.

- ↑ Sharp H, Bridges R, Krivit W, Freier E (1969). "Cirrhosis associated with alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency: a previously unrecognized inherited disorder". J Lab Clin Med. 73 (6): 934–9. PMID 4182334.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. |

- Alpha-1 Disease Management Program at AlphaNet

- Alpha-1 Foundation

- FAQ from AlphaNet

- Alpha-1 Kids

- Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency on Orphanet

- Alpha 1-antitrypsin at Lab Tests Online

- Children's Liver Disease Foundation

- http://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/disorders/singlegene/a1ad/[]