Reactive armour

Reactive armor is a type of vehicle armor that reacts in some way to the impact of a weapon to reduce the damage done to the vehicle being protected. It is most effective in protecting against shaped charges and specially hardened kinetic energy penetrators. The most common type is explosive reactive armor (ERA), but variants include self-limiting explosive reactive armor (SLERA), non-energetic reactive armor (NERA), non-explosive reactive armor (NxRA), and electric reactive armor. Unlike ERA and SLERA, NERA and NxRA modules can withstand multiple hits, but a second hit in exactly the same location will still penetrate.

Essentially all anti-tank munitions work by piercing the armor and killing the crew inside, disabling vital mechanical systems, or both. Reactive armor can be defeated with multiple hits in the same place, as by tandem-charge weapons, which fire two or more shaped charges in rapid succession. Without tandem charges, hitting the same spot twice is much more difficult.

History

The idea of counterexplosion (kontrvzryv in Russian) in armour was first proposed by the Scientific Research Institute of Steel (NII Stali) in 1949 in the USSR by academician Bogdan Vjacheslavovich Voitsekhovsky (1922–1999). The first pre-production models were produced during the 1960s. However, insufficient theoretical analysis during one of the tests resulted in all of the prototype elements being blown up. For a number of reasons, including the accident, as well as a belief that Soviet tanks had sufficient armour, the research was ended. No more research was conducted until 1974 when the Ministry of the Defensive Industry announced a contest to find the best tank protection project.

A West German researcher, Manfred Held carried out similar work with the IDF in 1967–69. Reactive armour created on the basis of the joint research was first installed on Israeli tanks during the 1982 Lebanon war and was judged very effective.

Explosive reactive armour

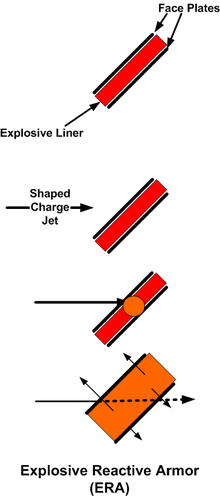

An element of explosive reactive armour consists of a sheet or slab of high explosive sandwiched between two plates, typically metal, called the reactive or dynamic elements. On attack by a penetrating weapon, the explosive detonates, forcibly driving the metal plates apart to damage the penetrator. Against a shaped charge, the projected plates disrupt the metallic jet penetrator, effectively providing a greater path-length of material to be penetrated. Against a kinetic energy penetrator, the projected plates serve to deflect and break up the rod.

The disruption is attributed to two mechanisms. First, the moving plates change the effective velocity and angle of impact of the shaped charge jet, reducing the angle of incidence and increasing the effective jet velocity versus the plate element. Second, since the plates are angled compared to the usual impact direction of shaped charge warheads, as the plates move outwards the impact point on the plate moves over time, requiring the jet to cut through fresh plate material. This second effect significantly increases the effective plate thickness during the impact.

To be effective against kinetic energy projectiles, ERA must use much thicker and heavier plates and a correspondingly thicker explosive layer. Such "heavy ERA," such as the Soviet-developed Kontakt-5, can break apart a penetrating rod that is longer than the ERA is deep, again significantly reducing penetration capability.

An important aspect of ERA is the brisance, or detonation speed of its explosive element. A more brisant explosive and greater plate velocity will result in more plate material being fed into the path of the oncoming jet, greatly increasing the plate's effective thickness. This effect is especially pronounced in the rear plate receding away from the jet, which triples in effective thickness with double the velocity.[1]

ERA also counters explosively forged projectiles, as produced by a shaped charge. The counter-explosion must disrupt the incoming projectile so that its momentum is distributed in all directions rather than towards the target, greatly diminishing its effectiveness.

Explosive reactive armour has been valued by the Soviet Union and its now-independent component states since the 1980s, and almost every tank in the eastern-European military inventory today has either been manufactured to use ERA or had ERA tiles added to it, including even the T-55 and T-62 tanks built forty to fifty years ago, but still used today by reserve units. The U.S. Army uses reactive armour on its Abrams tanks as part of the TUSK (Tank Urban Survivability Kit) package and on Bradley vehicles and the Israelis use it frequently on their American built M60 tanks.

ERA tiles are used as add-on (or "appliqué") armour to the portions of an armoured fighting vehicle that are most likely to be hit, typically the front (glacis) of the hull and the front and sides of the turret. Their use requires that a vehicle be fairly heavily armoured to protect itself and its crew from the exploding ERA.

A further complication to the use of ERA is the inherent danger to anyone near the tank when a plate detonates, disregarding that a high explosive anti-tank warhead (HEAT) warhead explosion would already cause great danger to anyone near the tank. Although ERA plates are intended only to bulge following detonation, the combined energy of the ERA explosive, coupled with the kinetic or explosive energy of the projectile, will frequently cause explosive fragmentation of the plate. The explosion of an ERA plate creates a significant amount of shrapnel, and bystanders are in grave danger of fatal injury. Thus, infantry must operate some distance from vehicles protected by ERA in combined arms operations.

Non-explosive and non-energetic reactive armour

NERA and NxRA operate similarly to explosive reactive armour, but without the explosive liner. Two metal plates sandwich an inert liner, such as rubber.[2] When struck by a shaped charge's metal jet, some of the impact energy is dissipated into the inert liner layer, and the resulting high pressure causes a localized bending or bulging of the plates in the area of the impact. As the plates bulge, the point of jet impact shifts with the plate bulging, increasing the effective thickness of the armour. This is almost the same as the second mechanism that explosive reactive armour uses, but it uses energy from the shaped charge jet rather than from explosives.[3]

Since the inner liner is non-explosive, the bulging is less energetic than on explosive reactive armour, and thus offers less protection than a similarly-sized ERA. However, NERA and NxRA are lighter, safe to handle, safer for nearby infantry, can theoretically be placed on any part of the vehicle, and can be packaged in multiple spaced layers if needed. A key advantage of this kind of armour is that it cannot be defeated via tandem warhead shaped charges, which employ a small forward warhead to detonate ERA before the main warhead fires.

Electric reactive armour

A new technology called electric reactive armour (also termed electromagnetic reactive armour, or colloquially as electric armour) is in development. This armour is made up of two or more conductive plates separated by an air gap or by an insulating material, creating a high-power capacitor.[4][5][6][7][8] In operation, a high-voltage power source charges the armour. When an incoming body penetrates the plates, it closes the circuit to discharge the capacitor, dumping a great deal of energy into the penetrator, which may vaporize it or even turn it into a plasma, significantly diffusing the attack. It is not public knowledge whether this is supposed to function against both kinetic energy penetrators and shaped charge jets, or only the latter. This technology has not yet been introduced on any known operational platform.

An alternative design to ERA uses layers of plates of electromagnetic metal with silicone spacers on alternate sides. The damage to the exterior of the armour passes electricity into the plates causing them to magnetically move together. As the process is completed at the speed of electricity the plates are moving when struck by the projectile causing the projectile energy to be deflected whilst the energy is also dissipated in parting the magnetically attracted plates.

Directed energy reactive armour

Some active protection systems, like the German AMAP-ADS or the American Iron Curtain, have explosive modules that destroy projectiles with a directed energy explosion. This type of explosive module is similar in concept to the classic ERA, but without the metal plates and with directed energy explosives. The composition materials of the explosive modules are not public. The designer of the AMAP-ADS claims that his AMAP-ADS systems are effective against EFP and APFSDS.

See also

For analyzing reactive plate velocities, the Gurney equations are commonly used.

References

General references

- Manfred Held: "Brassey's Essential Guide to Explosive Reactive Armour and Shaped Charges", Brassey 1999, ISBN 1-85753-225-2

Inline citations

- ↑ Held, Manfred (20 Aug 2004). "Dr.". Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics. 29 (4): 245. doi:10.1002/prep.200400051. Retrieved 20 Jan 2015.

- ↑ "Protection Systems For Future Armored Vehicles". Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ↑ Non-explosive energetic material and a reactive armour element using same, US Patent Application 20060011057, accessed August 29, 2007

- ↑ U.S. Military Uses the Force (Wired News)

- ↑ 'Star Trek' shields to protect supertanks (The Guardian)

- ↑ 'Electric armour' vaporises anti-tank grenades and shells - Telegraph

- ↑ Electrified Vehicle Armour Could Deflect Weapons

- ↑ Advanced Add-on Armor for Light Vehicles

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Reactive armour. |

- Defense Update: Reactive Armor Suits

- Defense Update: Advanced Protection for Modern Armored Vehicles

- Defence Science and Technology Laboratory: Electric Armour - The threat of RPGs