Extraterrestrial atmosphere

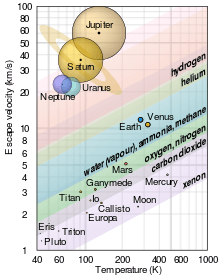

The study of extraterrestrial atmospheres is an active field of research,[1] both as an aspect of astronomy and to gain insight into Earth's atmosphere.[2] In addition to Earth, many of the other astronomical objects in the Solar System have atmospheres. These include all the gas giants, as well as Mars, Venus, and Pluto. Several moons and other bodies also have atmospheres, as do comets and the Sun. There is evidence that extrasolar planets can have an atmosphere. Comparisons of these atmospheres to one another and to Earth's atmosphere broaden our basic understanding of atmospheric processes such as the greenhouse effect, aerosol and cloud physics, and atmospheric chemistry and dynamics.

Planets

Inner planets

Mercury

Due to its small size (and thus its small gravity), Mercury has no substantial atmosphere. Its extremely thin atmosphere mostly consists of a small amount of helium and traces of sodium, potassium, and oxygen. These gases derive from the solar wind, radioactive decay, meteor impacts, and breakdown of Mercury's crust.[3][4] Mercury's atmosphere is not stable and is constantly being refreshed because of its atoms escaping into space as a result of the planet's heat.

Venus

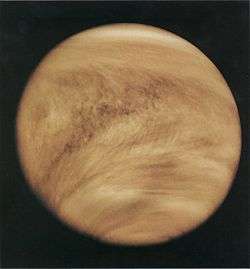

Venus' atmosphere is mostly composed of carbon dioxide. It contains minor amounts of nitrogen and other trace elements, including compounds based on hydrogen, nitrogen, sulfur, carbon, and oxygen. The atmosphere of Venus is much hotter and denser than that of Earth, though shallower. As greenhouse gases warm a lower atmosphere, they cool the upper atmosphere, leading to compact thermospheres.[5][6] By some definitions, Venus has no stratosphere.

The troposphere begins at the surface and extends up to an altitude of 65 kilometres (an altitude at which the mesosphere has already been reached on Earth). At the top of the troposphere, temperature and pressure reach Earth-like levels. Winds at the surface are a few metres per second, reaching 70 m/s or more in the upper troposphere. The stratosphere and mesosphere extend from 65 km to 95 km in height. The thermosphere and exosphere begin at around 95 kilometres, eventually reaching the limit of the atmosphere at about 220 to 250 km.

The air pressure at Venus' surface is about 92 times that of the Earth. The enormous amount of CO2 in the atmosphere creates a strong greenhouse effect, raising the surface temperature to around 470 °C, hotter than that of any other planet in the Solar System.

Mars

The Martian atmosphere is very thin and composed mainly of carbon dioxide, with some nitrogen and argon. The average surface pressure on Mars is 0.6-0.9 kPa, compared to about 101 kPa for Earth. This results in a much lower atmospheric thermal inertia, and as a consequence Mars is subject to strong thermal tides that can change total atmospheric pressure by up to 10%. The thin atmosphere also increases the variability of the planet's temperature. Martian surface temperatures vary from lows of approximately −140 °C (−220 °F) during the polar winters to highs of up to 20 °C (70 °F) in summers.

Between the Viking and Mars Global Surveyor missions, Mars saw "Much colder (10-20 K) global atmospheric temperatures were observed during the 1997 versus 1977 perihelion periods" and "that the global aphelion atmosphere of Mars is colder, less dusty, and cloudier than indicated by the established Viking climatology,"[7] with "generally colder atmospheric temperatures and lower dust loading in recent decades on Mars than during the Viking Mission."[8] The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, though spanning a much shorter dataset, shows no warming of planetary average temperature, and a possible cooling. "MCS MY 28 temperatures are an average of 0.9 (daytime) and 1.7 K (night- time) cooler than TES MY 24 measurements."[9] Locally and regionally, however, changes in pits in the layer of frozen carbon dioxide at the Martian south pole observed between 1999 and 2001 suggest the south polar ice cap is shrinking. More recent observations indicate that Mars' south pole is continuing to melt. "It's evaporating right now at a prodigious rate," says Michael Malin, principal investigator for the Mars Orbiter Camera.[10] The pits in the ice are growing by about 3 meters (9.8 ft) per year. Malin states that conditions on Mars are not currently conductive to the formation of new ice. A web site has suggested that this indicates a "climate change in progress" on Mars.[11] Multiple studies suggests this may be a local phenomenon rather than a global one.[12]

Colin Wilson has proposed that the observed variations are caused by irregularities in the orbit of Mars.[13] William Feldman speculates the warming could be because Mars might be coming out of an ice age.[14] Other scientists state the warming may be a result of albedo changes from dust storms.[15][16] The study predicts the planet could continue to warm, as a result of positive feedback.[16]

Gas giants

The four outer planets of the Solar System are gas giants. They share some atmospheric commonalities. All have atmospheres that are mostly hydrogen and helium and that blend into the liquid interior at pressures greater than the critical pressure, so that there is no clear boundary between atmosphere and body.

Jupiter

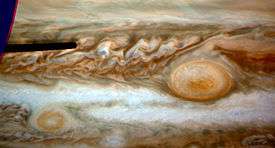

Jupiter's upper atmosphere is composed of about 75% hydrogen and 24% helium by mass, with the remaining 1% consisting of other elements. The interior contains denser materials such that the distribution is roughly 71% hydrogen, 24% helium and 5% other elements by mass. The atmosphere contains trace amounts of methane, water vapor, ammonia, and silicon-based compounds. There are also traces of carbon, ethane, hydrogen sulfide, neon, oxygen, phosphine, and sulfur. The outermost layer of the atmosphere contains crystals of frozen ammonia, possibly underlaid by a thin layer of water.

Jupiter is covered with a cloud layer about 50 km deep. The clouds are composed of ammonia crystals and possibly ammonium hydrosulfide. The clouds are located in the tropopause and are arranged into bands of different latitudes, known as tropical regions. These are sub-divided into lighter-hued zones and darker belts. The interactions of these conflicting circulation patterns cause storms and turbulence. The best-known feature of the cloud layer is the Great Red Spot, a persistent anticyclonic storm located 22° south of the equator that is larger than Earth. In 2000, an atmospheric feature formed in the southern hemisphere that is similar in appearance to the Great Red Spot, but smaller in size. The feature was named Oval BA, and has been nicknamed Red Spot Junior.

Observations of the Red Spot Jr. storm suggest Jupiter could be in a period of global climate change.[17][18] This is hypothesized to be part of an approximately 70 year global climate cycle, characterized by the relatively rapid forming and subsequent slow erosion and merging of cyclonic and anticyclonic vortices in Jupiter's atmosphere. These vortices facilitate the heat exchange between poles and equator. If they have sufficiently eroded, heat exchange is strongly reduced and regional temperatures may shift by as much as 10 K, with the poles cooling down and the equator region heating up. The resulting large temperature differential destabilizes the atmosphere and thereby leads to the creation of new vortices.[19][20]

Saturn

The outer atmosphere of Saturn consists of about 93.2% hydrogen and 6.7% helium. Trace amounts of ammonia, acetylene, ethane, phosphine, and methane have also been detected. As with Jupiter, the upper clouds on Saturn are composed of ammonia crystals, while the lower level clouds appear to be composed of either ammonium hydrosulfide (NH4SH) or water.

The Saturnian atmosphere is in several ways similar to that of Jupiter. It exhibits a banded pattern similar to Jupiter's, and occasionally exhibits long-lived ovals caused by storms. A storm formation analogous to Jupiter's Great Red Spot, the Great White Spot, is a short-lived phenomenon that forms with a roughly 30-year periodicity. It was last observed in 1990. However, the storms and the band pattern are less visible and active than those of Jupiter, due to the overlying ammonia hazes in Saturn's troposphere.

Saturn's atmosphere has several unusual features. Its winds are among the Solar System's fastest, with Voyager data indicating peak easterly winds of 500 m/s. It is also the only planet with a warm polar vortex, and is the only planet other than Earth where eyewall clouds have been observed in hurricane-like structures.

Uranus

The atmosphere of Uranus is composed primarily of gas and various ices. It is about 83% hydrogen, 15% helium, 2% methane and traces of acetylene. Like Jupiter and Saturn, Uranus has a banded cloud layer, although this is not readily visible without enhancement of visual images of the planet. Unlike the larger gas giants, the low temperatures in the upper Uranian cloud layer, down to 50 K, causes cloud formation from methane rather than ammonia.

Less storm activity has been observed in the Uranian atmosphere than in those of Jupiter or Saturn, due to the overlying methane and acetylene hazes in its atmosphere making the planet look like a bland, light blue globe. Images taken in 1997 with the Hubble Space Telescope showed storm activity in that part of the atmosphere emerging from the 25-year-long Uranian winter. The general lack of storm activity may be related to the lack of an internal energy generation mechanism for Uranus, a feature unique among the gas giants.[21]

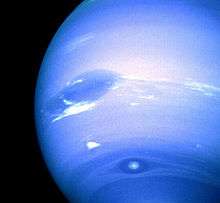

Neptune

The atmosphere of Neptune is similar to that of Uranus. It is about 80% hydrogen, 19% helium, and 1.5% methane. However the weather activity on Neptune is much more active, and its atmosphere is much bluer than that of Uranus. The upper levels of the atmosphere reach temperatures of about 55 K, giving rise to methane clouds in its troposphere, which gives the planet its ultramarine color. Temperatures rise steadily deeper inside the atmosphere.

Neptune has extremely dynamic weather systems, including the highest wind speeds in the Solar System, thought to be powered by the flow of internal heat. Typical winds in the banded equatorial region can possess speeds of around 350 m/s, while storm systems can have winds reaching up to around 900 m/s, nearly the speed of sound in Neptune's atmosphere. Several large storm systems have been identified, including the Great Dark Spot, a cyclonic storm system the size of Eurasia, the Scooter, a white cloud group further south than the Great Dark Spot, and the Wizard's eye/Dark Spot 2, a southern cyclonic storm.

Neptune, the farthest planet from Earth, has increased in brightness since 1980. Neptune's brightness is statistically correlated with its stratospheric temperature. Hammel and Lockwood hypothesize that the change in brightness includes a solar variation component as well as a seasonal component, though they did not find a statistically significant correlation with solar variation. They propose that the resolution of this issue will be clarified by brightness observations in the next few years: forcing by a change in sub-solar latitude should be reflected in a flattening and decline of brightness, while solar forcing should be reflected in a flattening and then resumed rise of brightness.[22]

Other bodies in the Solar System

Natural satellites

Ten of the many natural satellites in the Solar System are known to have atmospheres: Europa, Io, Callisto, Enceladus, Ganymede, Titan, Rhea, Dione, Triton and Earth's Moon. Ganymede and Europa both have very tenuous oxygen atmospheres, thought to be produced by radiation splitting the water ice present on the surface of these moons into hydrogen and oxygen. Io has an extremely thin atmosphere consisting mainly of sulfur dioxide (SO

2), arising from volcanism and sunlight-driven sublimation of surface sulfur dioxide deposits. The atmosphere of Enceladus is also extremely thin and variable, consisting mainly of water vapor, nitrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide vented from the moon's interior through cryovolcanism. The extremely thin carbon dioxide atmosphere of Callisto is thought to be replenished by sublimation from surface deposits.

Moon

Titan

Titan has by far the densest atmosphere of any moon. The Titanean atmosphere is in fact denser than Earth's, with a surface pressure of 147 kPa, one and a half times that of the Earth. The atmosphere is 98.4% nitrogen, with the remaining 1.6% composed of methane and trace amounts of other gases such as hydrocarbons (including ethane, diacetylene, methylacetylene, cyanoacetylene, acetylene, propane), argon, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, cyanogen, hydrogen cyanide and helium. The hydrocarbons are thought to form in Titan's upper atmosphere in reactions resulting from the breakup of methane by the Sun's ultraviolet light, producing a thick orange smog. Titan has no magnetic field and sometimes orbits outside Saturn's magnetosphere, directly exposing it to the solar wind. This may ionize and carry away some molecules from the top of the atmosphere.

Titan's atmosphere supports an opaque cloud layer that obscures Titan's surface features at visible wavelengths. The haze that can be seen in the adjacent picture contributes to the moon's anti-greenhouse effect and lowers the temperature by reflecting sunlight away from the satellite. The thick atmosphere blocks most visible wavelength light from the Sun and other sources from reaching Titan's surface.

Triton

Triton, Neptune's largest moon, has a tenuous nitrogen atmosphere with small amounts of methane. Tritonian atmospheric pressure is about 1Pa. The surface temperature is at least 35.6 K, with the nitrogen atmosphere in equilibrium with nitrogen ice on Triton's surface.

Triton has increased in absolute temperature by 5% since 1989 to 1998.[23][24] A similar rise of temperature on Earth would be equal to about 11 °C (20 °F) increase in temperature in nine years. "At least since 1989, Triton has been undergoing a period of global warming. Percentage-wise, it's a very large increase," said James L. Elliot, who published the report.[23]

Triton is approaching an unusually warm summer season that only happens once every few hundred years. Elliot and his colleagues believe that Triton's warming trend could be driven by seasonal changes in the absorption of solar energy by its polar ice caps. One suggestion for this warming is that it is a result of frost patterns changing on its surface. Another is that ice albedo has changed, allowing for more heat from the Sun to be absorbed.[25] Bonnie J. Buratti et al. argue the changes in temperature are a result of deposition of dark, red material from geological processes on the moon, such as massive venting. Because Triton's Bond albedo is among the highest within the Solar System, it is sensitive to small variations in spectral albedo.[26]

Pluto

Near-sunset view includes several layers of atmospheric haze.

Pluto has an extremely thin atmosphere that consists of nitrogen, methane, and carbon monoxide, derived from the ices on its surface.[27] Two models [28][29] show that the atmosphere does not completely freeze and collapse when Pluto moves further from the Sun on its extremely elliptical orbit. However, some do. Pluto needs 248 years for one complete orbit, and has been observed for less than one third of that time. It has an average distance of 39 AU from the Sun, hence in-depth data from Pluto is sparse and difficult to gather. Temperature is inferred indirectly for Pluto; when it passes in front of a star, observers note how fast the light drops off. From this, they deduce the density of the atmosphere, and that is used as an indicator of temperature.

One such occultation events happened in 1988. Observations of a second occulation on August 20, 2002 suggest that Pluto's atmospheric pressure has tripled, indicating a warming of about 2 °C (3.6 °F),[30][31] as predicted by Hansen and Paige.[32] The warming is "likely not connected with that of the Earth," says Jay Pasachoff.[33] One astronomer has speculated the warming may be a result of eruptive activity, but it is more likely Pluto's temperature is heavily influenced by its elliptical orbit. It was closest to the Sun in 1989 (perihelion) and has slowly receded since. If it has any thermal inertia, it is expected to warm for a while after it passes perihelion.[34] "This warming trend on Pluto could easily last for another 13 years," says David J. Tholen.[30] It has also been suggested that a darkening of surface ice may also be the cause, but additional data and modeling is needed. Frost distribution on the surface of Pluto is significantly affected by the dwarf planet's high obliquity.[35]

Exoplanets

Several planets outside the Solar System (exoplanets) have been observed to have atmospheres. At the present time, all atmosphere detections are of hot Jupiters or hot Neptunes that orbit very close to their star and thus have heated and extended atmospheres. Observations of exoplanet atmospheres are of two types. First, transmission photometry or spectra detect the light that passes through a planet's atmosphere as it transits in front of its star. Second, the direct emission from a planet atmosphere may be detected by differencing the star plus planet light obtained during most of the planet's orbit with the light of just the star during secondary eclipse (when the exoplanet is behind its star).

The first observed extrasolar planetary atmosphere was made in 2001.[36] Sodium in the atmosphere of the planet HD 209458 b was detected during a set of four transits of the planet across its star. Later observations with the Hubble Space Telescope showed an enormous ellipsoidal envelope of hydrogen, carbon and oxygen around the planet. This envelope reaches temperatures of 10,000 K. The planet is estimated to be losing (1-5)×108 kg of hydrogen per second. This type of atmosphere loss may be common to all planets orbiting Sun-like stars closer than around 0.1 AU.[37] In addition to hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen, HD 209458 b is thought to have water vapor in its atmosphere.[38][39][40] Water vapour has also been observed in the atmosphere of HD 189733 b,[41] another hot gas giant planet.

In October 2013, the detection of clouds in the atmosphere of Kepler-7b was announced,[42][43] and, in December 2013, also in the atmospheres of GJ 436 b and GJ 1214 b.[44][45][46][47]

Atmospheric composition

In 2001, sodium was detected in the atmosphere of HD 209458 b.[48]

In 2008, water, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide[49] and methane[50] were detected in the atmosphere of HD 189733 b.

In 2013, water was detected in the atmospheres of HD 209458 b, XO-1b, WASP-12b, WASP-17b, and WASP-19b.[51][52][53]

In July 2014, NASA announced finding very dry atmospheres on three exoplanets (HD 189733b, HD 209458b, WASP-12b) orbiting Sun-like stars.[54]

In September 2014, NASA reported that HAT-P-11b is the first Neptune-sized exoplanet known to have a relatively cloud-free atmosphere and, as well, the first time molecules of any kind have been found, specifically water vapor, on such a relatively small exoplanet.[55]

The presence of oxygen may be detectable by ground-based telescopes,[56] which, if discovered, would suggest the presence of photosynthetic life on an exoplanet.

In June 2015, NASA reported that WASP-33b has a stratosphere. Ozone and hydrocarbons absorb large amounts of ultraviolet radiation, heating the upper parts of atmosphere's that contain them, creating a temperature inversion and a stratosphere. However, these molecules are destroyed at the temperatures of hot exoplanets, creating doubt if the hot exoplanets could have a stratosphere. A temperature inversion, and stratosphere was identified on WASP-33b caused by titanium oxide, which is a strong absorber of visible and ultraviolet radiation, and can only exist as a gas in a hot atmosphere. WASP-33b is the hottest exoplanet known, with a temperature of 3,200 °C (5,790 °F)[57] and is approximately four and a half times the mass of Jupiter.[58][59]

In February 2016, it was announced that NASA's Hubble Space Telescope had detected hydrogen and helium (and suggestions of hydrogen cyanide), but no water vapor, in the atmosphere of 55 Cancri e, the first time the atmosphere of a super-earth exoplanet was analyzed successfully.[60]

Atmospheric circulation

The atmospheric circulation of planets that rotate more slowly or have a thicker atmosphere allows more heat to flow to the poles which reduces the temperature differences between the poles and the equator.[61]

Clouds

In October 2013, the detection of clouds in the atmosphere of Kepler-7b was announced,[42][43] and, in December 2013, also in the atmospheres of GJ 436 b and GJ 1214 b.[44][45][46][47]

Precipitation

Precipitation in the form of liquid (rain) or solid (snow) varies in composition depending on atmospheric temperature, pressure, composition, and altitude. Hot atmospheres could have iron rain,[62] molten-glass rain,[63] and rain made from rocky minerals such as enstatite, corundum, spinel, and wollastonite.[64] Deep in the atmospheres of gas giants, it could rain diamonds[65] and helium containing dissolved neon.[66]

Abiotic oxygen

There are geological and atmospheric processes that produce free oxygen, so the detection of oxygen is not necessarily an indication of life.[67]

The processes of life result in a mixture of chemicals that are not in chemical equilibrium but there are also abiotic disequilibrium processes that need to be considered. The most robust atmospheric biosignature is often considered to be molecular oxygen (O

2) and its photochemical byproduct ozone (O

3). The photolysis of water (H

2O) by UV rays followed by hydrodynamic escape of hydrogen can lead to a build-up of oxygen in planets close to their star undergoing runaway greenhouse effect. For planets in the habitable zone, it was thought that water photolysis would be strongly limited by cold-trapping of water vapour in the lower atmosphere. However, the extent of H2O cold-trapping depends strongly on the amount of non-condensible gases in the atmosphere such as nitrogen N2 and argon. In the absence of such gases, the likelihood of build-up of oxygen also depends in complex ways on the planet's accretion history, internal chemistry, atmospheric dynamics, and orbital state. Therefore, oxygen, on its own, cannot be considered a robust biosignature.[68] The ratio of nitrogen and argon to oxygen could be detected by studying thermal phase curves[69] or by transit transmission spectroscopy measurement of the spectral Rayleigh scattering slope in a clear-sky (i.e. aerosol-free) atmosphere.[70]

See also

References

- ↑ "Department of Atmospheric Science, University of Washington". Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- ↑ "NASA GISS: Research in Planetary Atmospheres". Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- ↑ Atmosphere of Mercury

- ↑ ESA Science & Technology: Mercury Atmosphere

- ↑ Picone, J.; Lean, J. (2005). "Global Change in the Thermosphere: Compelling Evidence of a Secular Decrease in Density". 2005 NRL Review: 225–227.

- ↑ Lewis, H.; et al. (April 2005). "Response of the Space Debris Environment to Greenhouse Cooling". Proceedings of the 4th European Conference on Space Debris: 243.

- ↑ Clancy, R. (April 25, 2000). "An intercomparison of ground-based millimeter, MGS TES, and Viking atmospheric temperature measurements: Seasonal and interannual variability of temperatures and dust loading in the global Mars atmosphere". Journal of Geophysical Research. 105 (4): 9553–9571. Bibcode:2000JGR...105.9553C. doi:10.1029/1999JE001089.

- ↑ Bell, J; et al. (August 28, 2009). "Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Mars Color Imager (MARCI): Instrument Description, Calibration, and Performance". Journal of Geophysical Research. 114 (8). Bibcode:2009JGRE..114.8S92B. doi:10.1029/2008je003315.

- ↑ Bandfield, J. L.; et al. (2013). "Radiometric Comparison of Mars Climate Sounder and Thermal Emission Spectrometer Measurements". Icarus. 225: 28–39. Bibcode:2013Icar..225...28B. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2013.03.007.

- ↑ Reddy, Francis (2005-09-23). "MGS sees changing face of Mars". Astronomy. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ↑ "Orbiter's Long Life Helps Scientists Track Changes on Mars". NASA. 2005-09-20. Archived from the original on April 30, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- ↑ Liu, J.; Richardson, M. (August 2003). "An assessment of the global, seasonal, and interannual spacecraft record of Martian climate in the thermal infrared". Journal of Geophysical Research. 108 (8). Bibcode:2003JGRE..108.5089L. doi:10.1029/2002je001921.

- ↑ Ravilious, Kate (2007-03-28). "Mars Melt Hints at Solar, Not Human, Cause for Warming, Scientist Says". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- ↑ "Mars Emerging from Ice Age, Data Suggest". Space.com. 2003-12-08. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ↑ Fenton, Lori K.; et al. (2007-04-05). "Global warming and climate forcing by recent of albedo changes on Mars" (PDF). Nature. 446 (7136): 646–649. Bibcode:2007Natur.446..646F. doi:10.1038/nature05718. PMID 17410170. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- 1 2 Ravilious, Kate (2007-04-04). "Mars Warming Due to Dust Storms, Study Finds". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ Marcus, Philip S.; et al. (November 2006). "Velocities and Temperatures of Jupiter's Great Red Spot and the New Red Oval and Implications for Global Climate Change". American Physical Society. Bibcode:2006APS..DFD.FG005M.

- ↑ Goudarzi, Sara (2006-05-04). "New Storm on Jupiter Hints at Climate Change". Space.com. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- ↑ Marcus, Philip S. (2004-04-22). "Prediction of a global climate change on Jupiter" (PDF). Nature. 428 (6985): 828–831. Bibcode:2004Natur.428..828M. doi:10.1038/nature02470. PMID 15103369. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- ↑ Yang, Sarah (2004-04-21). "Researcher predicts global climate change on Jupiter as giant planet's spots disappear". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- ↑ "Uranus' Atmosphere". Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ↑ http://www.agu.org/pubs/crossref/2007/2006GL028764.shtml

- 1 2 "MIT researcher finds evidence of global warming on Neptune's largest moon". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 1998-06-24. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ↑ Elliot, James L.; et al. (1998-06-25). "Global warming on Triton". Nature. 393 (6687): 765–767. Bibcode:1998Natur.393..765E. doi:10.1038/31651. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ↑ "Global Warming Detected on Triton". Scienceagogo.com. 1998-05-28. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ↑ Buratti, Bonnie J.; et al. (1999-01-21). "Does global warming make Triton blush?" (PDF). Nature. 397 (6716): 219–20. Bibcode:1999Natur.397..219B. doi:10.1038/16615. PMID 9930696. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ↑ Ken Croswell (1992). "Nitrogen in Pluto's Atmosphere". Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ↑ Hansen, C; Paige, D (Apr 1996). "Seasonal Nitrogen Cycles on Pluto". Icarus. 120: 247–265. Bibcode:1996Icar..120..247H. doi:10.1006/icar.1996.0049.

- ↑ Olkin, C; Young, L; et al. (March 2014). "Evidence That Pluto's Atmosphere Does Not Collapse From Occultations Including The 2013 May 04 Event". Icarus. 246: 220–225. Bibcode:2015Icar..246..220O. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2014.03.026.

- 1 2 Britt, Roy (2002-10-09). "Global Warming on Pluto Puzzles Scientists". Space.com. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- ↑ Elliot, James L.; et al. (2003-07-10). "The recent expansion of Pluto's atmosphere" (PDF). Nature. 424 (6945): 165–168. Bibcode:2003Natur.424..165E. doi:10.1038/nature01762. PMID 12853949. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-04-17. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ↑ http://plutopostcards.tumblr.com/post/81423347202/so-whats-the-deal-w-plutos-atmosphere-when-i/. Retrieved Mar 2015. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ "Pluto is undergoing global warming, researchers find". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 2002-10-09. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- ↑ Lakdawalla, E. (April 17, 2013). "Pluto's atmosphere does not collapse". Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ↑ Hansen, Candice J.; Paige, David A. (April 1996). "Seasonal Nitrogen Cycles on Pluto". Icarus. 120 (2): 247–265. Bibcode:1996Icar..120..247H. doi:10.1006/icar.1996.0049. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ↑ Charbonneau, David; et al. (2002). "Detection of an Extrasolar Planet Atmosphere". The Astrophysical Journal. 568 (1): 377–384. arXiv:astro-ph/0111544

. Bibcode:2002ApJ...568..377C. doi:10.1086/338770.

. Bibcode:2002ApJ...568..377C. doi:10.1086/338770. - ↑ Hébrard G., Lecavelier Des Étangs A., Vidal-Madjar A., Désert J.-M., Ferlet R. (2003), Evaporation Rate of Hot Jupiters and Formation of Chthonian Planets, Extrasolar Planets: Today and Tomorrow, ASP Conference Proceedings, Vol. 321, held 30 June - 4 July 2003, Institut d'astrophysique de Paris, France. Edited by Jean-Philippe Beaulieu, Alain Lecavelier des Étangs and Caroline Terquem.

- ↑ Water Found in Extrasolar Planet's Atmosphere - Space.com

- ↑ Signs of water seen on planet outside solar system, by Will Dunham, Reuters, Tue April 10, 2007 8:44PM EDT

- ↑ Water Identified in Extrasolar Planet Atmosphere, Lowell Observatory press release, April 10, 2007

- ↑ Press Release: NASA's Spitzer Finds Water Vapor on Hot, Alien Planet

- 1 2 Chu, Jennifer (October 2, 2013). "Scientists generate first map of clouds on an exoplanet". MIT. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- 1 2 Demory, Brice-Olivier; et al. (September 30, 2013). "Inference of Inhomogeneous Clouds in an Exoplanet Atmosphere". The Astrophysical Journal. 776: L25. arXiv:1309.7894

. Bibcode:2013ApJ...776L..25D. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/776/2/L25.

. Bibcode:2013ApJ...776L..25D. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/776/2/L25. - 1 2 Harrington, J.D.; Weaver, Donna; Villard, Ray (December 31, 2013). "Release 13-383 - NASA's Hubble Sees Cloudy Super-Worlds With Chance for More Clouds". NASA. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- 1 2 Moses, Julianne (January 1, 2014). "Extrasolar planets: Cloudy with a chance of dustballs". Nature. 505: 31–32. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...31M. doi:10.1038/505031a. PMID 24380949. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- 1 2 Knutson, Heather; et al. (January 1, 2014). "A featureless transmission spectrum for the Neptune-mass exoplanet GJ 436b". Nature. 505: 66–68. arXiv:1401.3350

. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...66K. doi:10.1038/nature12887. PMID 24380953. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...66K. doi:10.1038/nature12887. PMID 24380953. Retrieved January 1, 2014. - 1 2 Kreidberg, Laura; et al. (January 1, 2014). "Clouds in the atmosphere of the super-Earth exoplanet GJ 1214b". Nature. 505: 69–72. arXiv:1401.0022

. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...69K. doi:10.1038/nature12888. PMID 24380954. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...69K. doi:10.1038/nature12888. PMID 24380954. Retrieved January 1, 2014. - ↑ Charbonneau, D.; Brown, T. M.; Noyes, R. W.; Gilliland, R. L. (2002). "Detection of an Extrasolar Planet Atmosphere". The Astrophysical Journal. 568: 377–384. arXiv:astro-ph/0111544

. Bibcode:2002ApJ...568..377C. doi:10.1086/338770.

. Bibcode:2002ApJ...568..377C. doi:10.1086/338770. - ↑ Swain, M. R.; Vasisht, G.; Tinetti, G.; Bouwman, J.; Chen, P.; Yung, Y.; Deming, D.; Deroo, P. (2009). "Molecular Signatures in the Near Infrared Dayside Spectrum of HD 189733b". The Astrophysical Journal. 690 (2): L114. arXiv:0812.1844

. Bibcode:2009ApJ...690L.114S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/690/2/L114.

. Bibcode:2009ApJ...690L.114S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/690/2/L114. - ↑ NASA – Hubble Finds First Organic Molecule on an Exoplanet. NASA. 19 March 2008

- ↑ "Hubble Traces Subtle Signals of Water on Hazy Worlds". NASA. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ Deming, D.; Wilkins, A.; McCullough, P.; Burrows, A.; Fortney, J. J.; Agol, E.; Dobbs-Dixon, I.; Madhusudhan, N.; Crouzet, N.; Desert, J. M.; Gilliland, R. L.; Haynes, K.; Knutson, H. A.; Line, M.; Magic, Z.; Mandell, A. M.; Ranjan, S.; Charbonneau, D.; Clampin, M.; Seager, S.; Showman, A. P. (2013). "Infrared Transmission Spectroscopy of the Exoplanets HD 209458b and XO-1b Using the Wide Field Camera-3 on the Hubble Space Telescope". The Astrophysical Journal. 774 (2): 95. arXiv:1302.1141

. Bibcode:2013ApJ...774...95D. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/774/2/95.

. Bibcode:2013ApJ...774...95D. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/774/2/95. - ↑ Mandell, A. M.; Haynes, K.; Sinukoff, E.; Madhusudhan, N.; Burrows, A.; Deming, D. (2013). "Exoplanet Transit Spectroscopy Using WFC3: WASP-12 b, WASP-17 b, and WASP-19 b". The Astrophysical Journal. 779 (2): 128. arXiv:1310.2949

. Bibcode:2013ApJ...779..128M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/779/2/128.

. Bibcode:2013ApJ...779..128M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/779/2/128. - ↑ Harrington, J.D.; Villard, Ray (24 July 2014). "RELEASE 14–197 – Hubble Finds Three Surprisingly Dry Exoplanets". NASA. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ Clavin, Whitney; Chou, Felicia; Weaver, Donna; Villard; Johnson, Michele (24 September 2014). "NASA Telescopes Find Clear Skies and Water Vapor on Exoplanet". NASA. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ↑ Kawahara, H.; Matsuo, T.; Takami, M.; Fujii, Y.; Kotani, T.; Murakami, N.; Tamura, M.; Guyon, O. (2012). "Can Ground-based Telescopes Detect the Oxygen 1.27 μm Absorption Feature as a Biomarker in Exoplanets?". The Astrophysical Journal. 758: 13. arXiv:1206.0558

. Bibcode:2012ApJ...758...13K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/758/1/13.

. Bibcode:2012ApJ...758...13K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/758/1/13. - ↑ "Hottest planet is hotter than some stars". Retrieved 2015-06-12.

- ↑ "NASA's Hubble Telescope Detects 'Sunscreen' Layer on Distant Planet". Retrieved 2015-06-11.

- ↑ Haynes, Korey; Mandell, Avi M.; Madhusudhan, Nikku; Deming, Drake; Knutson, Heather (2015-05-06). "Spectroscopic Evidence for a Temperature Inversion in the Dayside Atmosphere of the Hot Jupiter WASP-33b". The Astrophysical Journal. 806 (2): 146. arXiv:1505.01490

[astro-ph]. Bibcode:2015ApJ...806..146H. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/806/2/146.

[astro-ph]. Bibcode:2015ApJ...806..146H. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/806/2/146. - ↑ Staff (16 February 2016). "First detection of super-earth atmosphere". Phys.org. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ Showman, A. P.; Wordsworth, R. D.; Merlis, T. M.; Kaspi, Y. (2013). "Atmospheric Circulation of Terrestrial Exoplanets". Comparative Climatology of Terrestrial Planets: 277. arXiv:1306.2418

. Bibcode:2013cctp.book..277S. doi:10.2458/azu_uapress_9780816530595-ch12. ISBN 978-0-8165-3059-5.

. Bibcode:2013cctp.book..277S. doi:10.2458/azu_uapress_9780816530595-ch12. ISBN 978-0-8165-3059-5. - ↑ New World of Iron Rain. Astrobiology Magazine. 8 January 2003

- ↑ Howell, Elizabeth (30 August 2013) On Giant Blue Alien Planet, It Rains Molten Glass. SPACE.com

- ↑ Raining Pebbles: Rocky Exoplanet Has Bizarre Atmosphere, Simulation Suggests. Science Daily. 1 October 2009

- ↑ Morgan, James (14 October 2013) 'Diamond rain' falls on Saturn and Jupiter. BBC.

- ↑ Sanders, Robert (22 March 2010) Helium rain on Jupiter explains lack of neon in atmosphere. newscenter.berkeley.edu

- ↑ "Oxygen Is Not Definitive Evidence of Life on Extrasolar Planets". NAOJ. Astrobiology Web. 10 September 2015. Retrieved 2015-09-11.

- ↑ Wordsworth, R.; Pierrehumbert, R. (2014). "Abiotic Oxygen-Dominated Atmospheres on Terrestrial Habitable Zone Planets". The Astrophysical Journal. 785 (2): L20. arXiv:1403.2713

. Bibcode:2014ApJ...785L..20W. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/785/2/L20.

. Bibcode:2014ApJ...785L..20W. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/785/2/L20. - ↑ Selsis, F.; Wordsworth, R. D.; Forget, F. (2011). "Thermal phase curves of nontransiting terrestrial exoplanets". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 532: A1. arXiv:1104.4763

. Bibcode:2011A&A...532A...1S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201116654.

. Bibcode:2011A&A...532A...1S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201116654. - ↑ Benneke, B.; Seager, S. (2012). "Atmospheric Retrieval for Super-Earths: Uniquely Constraining the Atmospheric Composition with Transmission Spectroscopy". The Astrophysical Journal. 753 (2): 100. arXiv:1203.4018

. Bibcode:2012ApJ...753..100B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/753/2/100.

. Bibcode:2012ApJ...753..100B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/753/2/100.

Further reading

- Seager, Sara (2010). Exoplanet Atmospheres: Physical Processes. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11914-4 (Hardback); ISBN 978-0-691-14645-4 (Paperback).

- Marley, Mark S.; Ackerman, Andrew S.; Cuzzi, Jeffrey N.; Kitzmann, Daniel (2013). "Clouds and Hazes in Exoplanet Atmospheres". Comparative Climatology of Terrestrial Planets. arXiv:1301.5627

[astro-ph.EP]. doi:10.2458/azu_uapress_9780816530595-ch15. ISBN 978-0-8165-3059-5.≥

[astro-ph.EP]. doi:10.2458/azu_uapress_9780816530595-ch15. ISBN 978-0-8165-3059-5.≥