Mawza Exile

The Exile of Mawzaʻ (the expulsion of Yemenite Jews to Mawza') Hebrew: גלות מוזע, pronounced [ğalūt mawzaʻ]; 1679–1680, is considered the single most traumatic event experienced collectively by the Jews of Yemen,[1] in which Jews living in nearly all cities and towns throughout Yemen were banished by decree of the king, Imām al-Mahdi Ahmad, and sent to a dry and barren region of the country named Mawzaʻ to withstand their fate or to die. Only a few communities, viz., those Jewish inhabitants who lived in the far eastern quarters of Yemen (Nihm, al-Jawf, and Khawlan of the east) were spared this fate by virtue of their Arab patrons who refused to obey the king’s orders.[2] Many would die along the route and while confined to the hot and arid conditions of this forbidding terrain. After one year in exile, the exiles were called back to perform their usual tasks and labors for the indigenous Arab populations, who had been deprived of goods and services on account of their exile.

Background

With the rise to power of the Qāsimīd Imām, al-Mutawakkil Isma'il (1644–1676), there was a crucial turning point in the condition of Jews living under the Imamate kingdom of Yemen. He endorsed the most hostile policies toward his Jewish subjects, partly due to the claim that the Jews were aiding the Ottoman Turks during the local uprising against them.[3] The rise of the Shabbathian movement in Yemen in 1666 exacerbated the problems facing the community, calling into question their status as protected wards of the State. One decree led to another.[4] The king initially demanded their conversion to Islam and when they refused, he made them stand out in the sun without apparel for three days, which was later followed by harsher decrees. It is said that al-Mutawakkil Isma'il consulted with the religious scholars of Islam and sought to determine whether or not the laws concerning Jews in the Arabian Peninsula applied also to Yemen, citing Muhammad who was reported as saying, “There shall not be two religions in Arabia.” When it was determined that these laws did indeed apply to Yemen, since the country was an indivisible part of the Arabian Peninsula, it then became incumbent upon Jews living in Yemen to either convert to Islam or to leave the country. Yet, since the king fell ill and was bedridden, he did not presently perform his ill-designs to expel the Jews from his kingdom, but commanded the heir to his throne, al-Mahdi Ahmad, to do so.[5][6]

Al-Mahdi Ahmad of al-Ghirās, who is also known by the epithet Ṣafī al-Din (purity of religion), succeeded al-Mutawakkil Isma'il, but perpetuated the same hostilities toward his Jewish subjects as those made by his predecessor. Everything reached its climax between the years 1677 and 1680, when he ordered the destruction of the synagogues in Ṣanʻā’ and elsewhere.[7] By early summer of 1679, he gave an ultimatum unto his Jewish subjects, namely, that they had the choice of either converting to Islam, in which they’d be allowed to remain in the country, or of being killed by the sword. He gave to them three months to decide what they would do.[8]

The king’s words led to no small consternation amongst his Jewish subjects in Yemen, who immediately declared a time of public fasting and prayer, which they did both by night and day. Their plight soon became known to the local Yemeni tribesmen, whose chiefs and principal men pitied their condition and intervened on their behalf. They came before the king and enquired concerning the decree, and insisted that the Jews had been loyal to their king and had not offended the Arab peoples, neither had they done anything worthy of death, but should only be punished a little for their “obduracy” in what concerns the religion of Islam. The king, agreeing to their counsel, chose not to kill his Jewish subjects, but decided to banish them from his kingdom. They were to be sent to Zeilaʻ, a place along the African coast of the Red Sea, where they would be confined for life, or else repent and accept the tenets of Islam.[9]

Sanā’a

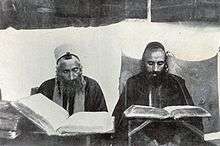

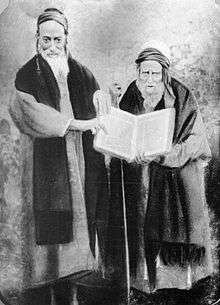

The Jewish community in Sana'a was concentrated in the neighborhood of al-Sā’ilah, within the walled city, as one enters Bab al-Shaʻub (the Shaʻub Gate) on Ṣan‘ā’s north side. The chief rabbi of the Jewish community at that time was an elder to whom they gave the title of Prince (Hanasi), Rabbi Suleiman al-Naqqāsh,[10] while the city's chief seat of learning was under the tutelage of Rabbi and Judge, Shelomo ben Saadia al-Manzeli (resh methivta).[11] The Jews of Ṣan‘ā’ were given but short notice about the things that were about to happen to them.[12] They had been advised to sell their houses, fields and vineyards, and that all property which they were unable to sell would automatically be confiscated and accrue to the Public Treasury (Ar. al-māl), without recompense.[13]

By late 1679, when the king saw that they were unrelenting in their fathers’ faith, he then decided to follow through with what he had determined for them and issued a decree, banishing all Jews in his kingdom to the Red Sea outpost known as Zeila‘. On the 2nd day of the lunar month Rajab, in the year 1090 of the Hijri calendar (corresponds with Gregorian calendar, August 10, 1679), his edict was put into effect, and he ordered the Jews of Ṣan‘ā’ to take leave of their places, but gave more space to the provincial governors of Yemen to begin the expulsion of all other Jews in Yemen to Zeila‘, and which should be accomplished by them in a time period not to exceed twelve months. The Jews of Ṣan‘ā’ had, meanwhile, set out on their journey, leaving behind them their homes and possessions, rather than exchange their religion for another. In doing so, they brought sanctity to God’s name.[14]

Rabbi Suleiman al-Naqqāsh, by his wisdom and care for his community, had preemptively made arrangements for the community’s safety and upkeep by sending written notifications to the Jewish communities which lay along the route, requesting that they provide food and assistance to their poor Jewish brethren when they passed through their communities in the coming weeks or days. The king’s soldiers were sent to escort the exiles unto their final destination, while the king himself had sent orders to the governors of the outlying districts and places where it was known that the Jewish exiles were to pass through while en route to Zeila‘, commanding them not to permit any Jew to remain in those cities when they reached them, but to send them on in their journey.[15]

Unexpected turn of events

Meanwhile, while columns of men, women and children were advancing by foot southward with only bare essentials, along the road leading from Ṣan‘ā’ to Dhamar, Yarim, ’Ibb and Ta‘izz, the chiefs of the indigenous Sabaean tribes who had been the patrons of the Jews came together once again and petitioned the king, al-Mahdi, this time requesting that the king rescind his order to expel all Jews unto the Red Sea outpost of Zeila‘, but to be content with their banishment to the Tihama coastal town of Mawza‘. The reason being for this urgent request was that, by taking into consideration their troubles in a barren wasteland, those that will remain of them will be more inclined to repent and to choose the way of Islam, in which case it will be easier to hoist them from that place and to bring them back unto their former places. The grandees reminded the king how they had been faithful in implementing his orders. At hearing this, the king agreed and sent orders to the effect that Jewish exiles should be conducted only to Mawza‘.[16]

By the time the Jews of Ṣan‘ā’ reached Dhamar, they had already been joined by the Jewish villagers of Siān and Tan‘am (located about 9.3 miles (15 km) eastward of Bayt al-Ḥāḍir, southeast Ṣan‘ā’), all of which places lie within Ṣan‘ā's periphery.[17] The Jews had sent fifteen letters to the king in al-Ghirās, asking him to forgive them of whatever offense they may have made and to permit them to remain in their former settlements, yet none of these did he answer.[18]

Evacuation of the Jews of Dhurān

Around the beginning of September of 1679, approximately one month after the Jews of Ṣan‘ā’ had set out for Mawza‛, Jews that hailed from Dhurān – a village situate about three days’ walking distance southwest of Ṣan‘ā’ – were also evacuated from their village. In a letter written in 1684 to the Jewish community of Hebron, only four years after the community’s return to Dhurān, the author describes the sufferings of the Jews who were forced to leave their homes and to go into Mawza‛.[19] One important revelation that emerges from his account of these events is that the Jews of Yemen had tried to pacify the king’s wrath by paying large sums of money to him, but which money the king refused to accept:

….On account of our many iniquities,[20] God stirred up the spirit of the king who dwells in this country to banish us; we and our wives and our children, unto a barren desert, a place of serpents and scorpions and scorching fire; wrath pursues [us], so that there has been fulfilled in us [the Scripture that says]: ‘And I shall bring them into the land of their enemies’ (Lev. 26:41). He has destroyed our synagogues, and has darkened the light of our eyes. ‘Go away! [You are] unclean!’ they cry out unto us, while the taskmasters are in a hurry, saying: ‘Go away from here; purify yourselves!’ (Isa. 52:11), and do not take pity upon any of your delectable things, lest the king should be sorely angry with you, [and] will kill you and your children, your aged men and your young men. Now if you should forsake your God whom you trust, and enter into our own religion, it will be well with you, seeing that He is no longer with you, but has already abandoned you in our hands; [we] being able to do with you as we please!’ …Now, there is no one who helps us, whether of the deputies or of the ministers, for when they saw that we had given-up our souls unto martyrdom for His name sake, and that we had been obedient to His word and speech, they then conspired against us to eradicate our name with fierce anger. They said [to us], ‘this despised and wretched nation, they have rejected our religion (i.e. Islam), whereas neither largess, nor gratis, would have made them come over.’ …They banded together against us, they and their kings, their male servants and handmaids, so that small babes spat upon him who is greatest amongst us. …Now, God has hidden His face from us, ‘while we have all faded like a leaf’ (Isa. 64:5). We went with shame and with reproach, in hunger and in thirst, and in nakedness and in deprivation of all things, unto that place which the king had decreed over us, for he had no wish for money, but rather in seeing our destruction.

The author goes on to explain how that, when they reached their destination, they wept bitterly, since many of them had perished as in a plague, and they were unable to bury them because of the excruciating heat. When some of their party had tried to escape at night, approximately seventy men, the next morning when the sun arose they were stricken down by the intense heat, and there they died. The author concludes by saying, "Now, this decree of exile was at the beginning of anno mundi 5440 (= 1679 CE), and the blessed God redeemed us at the [year's] end; the sign of which being: 'The punishment of your iniquity has ended ' (Lam. 4:22)." Here, the author makes a play on words; the Hebrew word for "ended" (Heb. תם) having the numerical value of 440, the same as the year when abbreviated without the millennium.[21]

Mawzaʻ

Mawzaʻ is a town situated eleven-days’ walking distance from Ṣan‘ā’, and ca. 12 miles (20 km) from the port of Mocha, in the Tihama coastal plain. During their long trek there, the king’s soldiers pressed them on. Many of the sick and elderly and children died along the way. Others would later succumb to the harsh weather conditions of that place. All, however, suffered from hunger and thirst. Eventually, the community of Ṣan‘ā’ was joined by other Jewish communities from across Yemen. In Mawzaʻ they remained for one full year, until 1680, when the king’s non-Jewish subjects began to complain about their lack of farm implements which had been exclusively made by Jewish craftsmen.[22] The governor of `Amran went personally before the king with a petition to bring back his Jewish subjects. The king acquiesced and sent emissaries bearing food and water to call them back to their former cities.[23] Some returned only to find their homes taken by usurping occupants. Others decided to move and to settle elsewhere in Yemen.[24]

Rabbi Hayim Hibshush, speaking somewhat about this time, writes: “For the duration of one year since this decree was first issued, they went as sheep to the slaughter from all the districts of Yemen, while none remained of all those districts who did not go into exile, excepting the district of Nihm towards the east, and the district of al-Jawf, as well as the eastern district of Khawlan.”[25]

Historical records

Rabbi Yiḥyah Salaḥ (who is known by the acronym Maharitz) gives a most captivating account of these harrowing events borne by the Jews of Ṣan‘ā’ in the years leading up to their expulsion, as also when they left their city, based on a hand-written document preserved and copied down by subsequent generations. Some have judged the sum and bearing of these events as a mere microscopic example of the sufferings experienced by the Jewish inhabitants as a whole, in each and every city throughout Yemen. Thus, he gives the following account:[26]

- "...In the year one thousand, nine-hundred and eighty-six [of the Seleucid Era] (1675 CE) the king named Isma'il died, and there was a famine and many died. Then Aḥmad, the son of Ḥasan, reigned in his stead, who was called al-Ḥasni, who expelled the Turks, and ruled by strength of arms, and was a man of exploits, and went up north and captured those districts, and went as far as to al-Yāfaʻ [in the south] and captured it. And in the year one thousand, nine-hundred and eighty-seven [of the Seleucid Era] (1676 CE), he destroyed the synagogues of the Jews. Then in the year one thousand, nine-hundred and eighty-eight [of the Seleucid Era] (1677 CE) there was a famine, and in the year one thousand, nine-hundred and eighty-nine (1678 CE) he expelled Israel unto the desert of Mawzaʻ,[27] which is a horrific place, and one known for its excruciating heat; its air being bad. No man could proceed upon the ground on account of their over weariness and the blisters which effected their feet.

- Now, during that same year, when they departed from Ṣan‘ā’ to go unto Mawzaʻ, there was a certain gentile unto whom they committed for safekeeping several scrolls of the Law and several books of the Talmud, and of Bible codices and of Midrashic literature [aplenty], as well as several leather-bound books which had been composed by the early scholars in their own hand-writing, for they were not able to carry them because of the encumbrance along the way, since they had been driven out on a sudden, they and their wives and children. Now these books nearly filled up one large room. They were of the opinion that they could appease the king, and that they would return to take their books. And it came to pass when they were gone away, that that [wicked] man arose and set fire to them, and burnt them all. On that very hour, Israel became impoverished in all things, whether on account of their shortage of books, or on account of their own novellæ and commentaries being burnt. Nothing remained except a few things of what little they had, of scrolls of the Law and Gemaras, and the other books which had been taken by the heads of the people in their own hands for their own needs in study and in reading from the books of the Law.

- Now while they ventured out in exile, several wise and pious men perished along the way, and several families were utterly taken away from off the face of the earth. Now, it has been told to us that about eighty souls died in one short period of time during one single journey in the desert, near the village of Mawzaʻ, on account of iniquities. On that upcoming Sabbath when they reached the village of Mawzaʻ it happened to be the Sabbath reading for the biblical lection known as Beḥuḳḳothai (Lev. 26:3-ff.)[28] and there stood up the greatest man amongst them to read the Reproofs, and when they came to the verse that says: And I shall bring them into the land of their enemies, perhaps then their uncircumcised heart should be brought under submission etc. (Lev. 26:41), and when he had then finished his reading, he began to expound [on that portion of the Law], and the spirit of God moved him, and he said that the present decree had been given from the start since ancient times, and is alluded to and is cleverly arranged and has been preserved in the acrostic at the end of each word [in the Hebrew verse], ’oyyaveihem ’o ’az yikana = אויביהם או אז יכנע (Lev. 26:41), [and which last letters spell out] Mawzaʻ! By the end of the year, the blessed God took mercy upon them and the king was appeased by agreeing to bring back the Jews, only he did not permit them to return to their former houses, but rather to build for themselves [new] houses outside of the city. And so it was.

- After these things, they settled in that place wherein the king had given to them to dwell, and they built houses. Now, in those days they appointed over themselves a Prince (Nagid), even the teacher and rabbi, Yiḥya Halevi, of blessed memory."

Aftermath

Those Jews who survived, who returned either to Ṣan‘ā’ or to the other towns and villages, were mostly ill from being exposed to the changes in climate and from the poor quality of drinking water. In Ṣan‘ā’, they were required to relinquish their ownership over their houses and fields within the city’s wall, in the neighborhood of al-Sā’ilah, and were directed to build humble abodes in a new area outside of the city’s walls, in a place then known as the “hyena’s field” (Ar. Qāʻ al-simaʻ), or what later became known as Qāʻ al-Yahud (the Jewish Quarter).[29] This place attracted other migrant Jews from the other towns and villages from which they had been expelled and soon grew into a suburb, situate about one kilometer beyond the walls which then existed on the extreme west-side of the city. Today, the place is called Qāʻ al-ʻUlufi (Ar. قاع العلفي).[30] The lands upon which they built the new Jewish Quarter were lands provided by the king, but the Jews were later required to pay a monthly tenancy fee for the land, and which money accrued to the Muslim Waqf (mortmain land) for the upkeep of their own places of worship. Between the new Jewish Quarter and the city walls was a suburb full of gardens called Bi’r alʻAzab (the Single’s Well), being once the Turkish Quarter.[31] In subsequent years, the Jewish Quarter was also enclosed by a wall.[32]

At that time, the Muslims passed a new edict which forbade Jews from dwelling within Muslim neighborhoods, so as not to “defile their habitations,” although they were at liberty to work in the city.[33] Those who traversed between the Jewish Quarter and the city would go by foot, while those who were either aged or ill would make use of beasts of burden to carry them into the city, the Jewish Quarter being then at a distance of about one-kilometer from the city’s walls. When these who had ridden upon donkeys were spied by the gentiles, they were presently envied by the gentiles, who then went unto the king and pressed upon him to outlaw their riding upon donkeys, saying that this mode of transportation seemed to be too extravagant for the Jews and would lead to a general unrest and eventual hegemony over the indigenous people. The king then passed a series of discriminatory laws (Ar. ghiyār) meant to humiliate the Jews and which not only forbade their riding upon donkeys and horses, but also from walking or passing to the right side of any Muslim. Jews were to pass only on the left side of all Muslims. They also petitioned the king that a Jew would be prohibited by an edict from raising his voice against any Muslim, but to behave in a lowly and contrite spirit, and that offenders would be made punishable by flogging.[34] Such were the conditions of the Jews at that time.

The Exile of Mawzaʻ brought about demographic changes that could be felt all across Yemen. In Ṣan‘ā’, to distinguish the original inhabitants from incoming migrant Jews, all newcomers who chose to dwell in the newly built Jewish Quarter were given surnames, each one after the place from which he was exiled, so that a man who came from the district of Sharʻab was called so-and-so, al-Sharʻabi, or he that came from the village of Maswar was called so-and-so, al-Maswari.[35] In the words of the Jewish chronicler who wrote Dofi Hazeman (Vicissitudes of Time), being one of the earliest Jewish accounts of the expulsion (initially compiled by Yaḥyā ben Judah Ṣa‘di in 1725) [36] and which work has since undergone several recensions by later chroniclers, we read the following testimony:[37]

He (i.e. the king) then commanded to give license unto the Jews to return unto the country and to build for themselves tents, although set apart from the houses of the Muslims so that they will not defile them. Those who were banished then came up from the Tihama [coastal plain], returning from Mawzaʻ; one man from a city and two from a family, for most of them had been consumed by the land of Tihama which dispenses of life. Neither had there remained any of them, save ten people for every hundred [who were driven out into exile], while the majority of them did not return to settle in their former place, but were scattered in all the districts of Yemen. That is, aside from the family of the Levites, most of whom returned and settled in their [former] place. Now their dwelling place was from the town of ash-Sharafah, eastward of Wadi al-Sirr, stretching as far as the town of al-‘Arus which lies in the region of Kawkaban, a walking distance of about one and a half days; as well as the breadth of the city of Ṣan‘ā’, stretching as far as the extremity of the land of Arḥab, being also a walking distance of one and a half days. These trace their lineage to Sasson the Levite, their ancestor, seeing that there was a law for the early Jews in Yemen for each family to dwell separately; the family of priests (Cohenim) by themselves with their burial grounds, and also the family of Levites and the Israelites, each of them dwelling by themselves in their cities and with their own burial grounds. Now, unto this day, those Levites dwell separately in those said districts, although a few Israelites have newly arrived to dwell in their midst. In every place, the gentiles have given to them a parcel of ground, on a rental basis, in order that they may construct shelters in which to live, set apart from them, seeing that their enemies had already taken [from them] their own towns and houses and vineyards and fields. Thus, they were pleased to dwell with them and to be occupied in the various fields of labour, according to their diverse skills, in order that they might find sustenance thereby for their beings: among which were those who plastered with earth, and of those who crushed limestone, and of those who were potters, and some who were wood craftsmen, and others silversmiths, while still others blacksmiths and some who were merchants; There were yet others who were couriers, some who were weavers, others tailors, and some who were knowledgeable in prophylactic matters; others who were physicians, and others who chiseled away the surface of millstones, and some of whom who were porters. Now their magnanimity did not permit them to just lay back in idleness.

Danish explorer, Carsten Niebuhr, who visited the Jewish Quarter of Ṣan‘ā’ in 1763, some eighty-three years following the community's return to Ṣan‘ā’, estimated their numbers at only two-thousand.[38] These had built, up until 1761, fourteen synagogues within the new Jewish Quarter. In 1902, before the famine of 1905 decimated more than half of the city's Jewish population, German explorer Hermann Burchardt estimated the Jewish population of Sana'a at somewhere between six to eight thousand.[39] By 1934, when Carl Rathjens visited Ṣan‘ā’, the Jewish population in the city had swollen to about seven thousand.[40]

Fate of the Old Synagogue

One of the outcomes of the king’s notorious decree was that Jewish property passed into Muslim hands. A Jewish public bath house in Ṣan‘ā’ was relinquished and passed into the proprietorship of the Muslim Waqf. So, too, the once famous synagogue within Ṣan‘ā’s walled city and which was known as Kenisat al-‘Ulamā (The Synagogue of the Sages) was turned into a mosque and called Masjid al-Jalā – the Mosque of the Expulsion, or “of those banished.” On the frieze (Ar. ṭiraz) of the Masjid al-Jalā were inscribed the words, in gypsum plaster (Ar. al-juṣ):

- “Our king, al-Mahdi, is the sun of [religious] guidance / even Aḥmad, the [grand]son of him who rose to power, al-Qasim. Unto him is ascribed dignities, such as were not accorded / before [to any other], even in part. Had he not done aught but banish / the Jews of Ṣan‘ā’, who are the ‘scum’ of the world, and turned their venerable place (Ar. bi‘ah = synagogue) into a mosque, / for bowing down unto God or standing [before Him in prayer], by that decree, he would have still been most triumphant. Now the time of this event happened to concur with the date that is [alluded to] in ghānim [victorious]”; Ghānim = (Arabic: غانم), the numerical value of which letters adds up to A.H. 1091 = 1680 CE).[41]

Rabbi Amram Qorah brings down a brief history of the said mosque, taken from a book originally drawn up in Arabic and which was entitled: A List of the Mosques of Ṣan‘ā’.[42] Therein is found a vivid description of the events which transpired in that fateful year and which reads as follows: “Among the mosques built in the vicinity of al-Sā’ilah, northwards from the path which leads from al-Sā’ilah to al-Quzālī, and the mosque [known as] Ben al-Ḥussein built by the Imam of the Qasimid dynasty, the son of Muhammad (i.e. al-Mahdi Ahmad b. al-Ḥasan b. al-Qasim b. Muhammad), in the year A.H. 1091 (= 1679 CE) in the synagogue of the Jewish Quarter, who banished them from Ṣan‘ā’ and removed them unto a place befitting them, [a place] now known as Qāʻ al-Yahud on the west side of Ṣan‘ā’, just as it has been intimated by the scholarly judge, Muhammad b. Ibrahim al-Suḥuli, etc.” Rabbi Amram Qorah then proceeds to bring down the words or panegyric inscribed on the frieze of the mosque in rhymed verse (see: supra), and which apparently had been composed by the said judge, in which he describes the exploits of the king who banished the Jews and who converted their synagogue into a mosque.[43]

Rabbi Amram Qorah, in the same work, brings down Rabbi Pinheas ben Gad Hacohen’s account of events, whose testimony he found written in the margin of the first page of a Prayer Book (Siddur), written in 1710:[44]

“Now I shall inform you, my brethren, about what has happened to us at this time, since the beginning of anno 1,990 of the Seleucid Era (1678 CE) and in 1,991 [of the same] (1679 CE), how that the king made a decree and demolished all the synagogues of all the towns of Yemen, and there were some of the books and sacred writings that were desecrated at the hand of the gentiles, on account of our great iniquities, so that we could no longer make our [public] prayers, save only a very few [men] secretly within their houses. Afterwards, the king made a decree against the Jews to expel them into the wilderness of Mawzaʻ, while they, [at this time] demolished also their houses. However, there were some who managed to sell their house; what was worth one-thousand gold pieces they sold for one-hundred, and what was worth one-hundred gold pieces they sold for ten. So that, by these things, we were for a reproach amongst the nations, who continuously sought after ways by which they might cause us to change [our religion], O may God forbid! So, all of the exiles of Yemen stood up and laid aside their most beloved and precious possessions as a means by which God's name might be sanctified, blessed be He, including their fields and their vineyards, and delivered themselves up as martyrs for God's name sake, blessed be He. And if one had need of going out into the marketplace, he could not avoid being the object of hatred and spite, while there were those who even attacked him or called him by abusive language, so that there was fulfilled in this, our generation, the scripture that says, Who will raise up Jacob, for he is too small (Amos 7: 2, 5) to bear all the afflictions. So, too, was there fulfilled in us by reason of our iniquities the scripture that says, And I shall send a faintness into their hearts (Lev. 26:36). Yet, the divine Name, blessed be He, gives us strength to bear all those troubles and travails each day.”

Testimonies preserved in poetry

Another man who witnessed these events, Shalem ‘Ashri, also wrote a suppliant poem about the events of that year – the Exile of Mawzaʻ, now preserved in the Yemenite Diwān,[45] which same poem is meant to be chanted as a slow dirge by one or, at the most, two individuals, who are then answered by others who sit in attendance. It is sung without the accompaniment of musical instruments, although a tin drum is sometimes used, in accordance with what is customary and proper for the nashid (a rejoinder). His own name is spelt out in acrostic form in the first letters of each stanza:[45]

“I shall shed my tears – like rain they shall pour down / over all the pleasant sons who have gone forth into exile. They have forgotten what pertains to their happiness, and have also been diminished. / They journeyed in haste; along the parched ground they trod. On the day when ’Uzal (i.e. Ṣan‘ā’)[46] went into exile, they took up his burden. The sun and the moon were extinguished at their departure! A multitude of the handmaid’s sons[47] have ruled over them. / Wrath, and also jealousy, they’ve poured out upon them. So that they have inherited all of the glory, even their sublime honour! Whilst the dwelling place of God’s glory, they have been given power to destroy! Midrash, as also the Talmud and the Torah, they have abolished. / Constable and elder were, both, drawn away by their hands. Orion and Pleiades, as well as the crescent moon, have become dim! / Even all the luminous lights, their light has turned into darkness! The beauty of their homes and their money they had entirely looted. / Every oppressor and every governor have prepared their bow for shooting. Preserve, O Master of the universe, those who are your peculiar friends, / Hadoram (i.e. Dhamar),[48] God’s congregation, have been drawn after you! The heads of their academies have borne patiently the exile, / to do even the will of God, having valued the commandments. Redeem, O Master of the universe, your friends who have inherited / the Divine Law and sound wisdom, by which they have been blest! For the honour due to the writing of thine own hand on the day when they were gathered,[49] / may you call to remembrance and deliver them during the time of their flight. My name is Shalem; ‘tis written in the locked rhyme. / Rejoice in God’s Divine Law, and bless His name!”

Original:

אזיל דמעותי כמטר יזלו / על כל בני חמדה בגלות הלכו. נשו לטובתם וגם נתדלדלו / נסעו בחפזון בציה דרכו. יום גלתה אוזל וסבלו סבלו / שמש וירח בצאתם נדעכו. שפעת בני אמה עליהם משלו / חמה וגם קנאה עליהם שפכו. לכלל יקר הדרת כבודם נחלו / ומעון כבוד האל להחריב נמלכו. מדרש וגם תלמוד ותורה בטלו / שוטר וגם זקן ידיהם משכו. עיש וגם כימה וסהר אפלו / גם כל מאורי אור מאורם חשכו. את כל נאות ביתם וכספם שללו / כל צר וכל מושל לקשתם דרכו. שמרה אדון עולם ידידים נסגלו / הדורם עדת האל אחריך נמשכו. ראשי ישיבתם לגלות סבלו / לעשות רצון האל ומצות ערכו. יגאל אדון עולם ידידים נחלו / תורה ותושיה ובה נתברכו. לכבוד כתב ידך ביום שנקהלו / תזכר ותצילם בעת יתהלכו. שלם שמי כתוב בחרוזים ננעלו / שמחו בתורת אל ולשמו ברכו.

In the following poem of the subgenre known as qiṣṣa (poetic tale), composed mostly in Judeo-Arabic with only two stanzas written in Hebrew, the author gives a long testimony about the events which transpired during that year of exile. The poem is entitled, Waṣalnā hātif al-alḥān – “Tidings have reached us,” and is the work of the illustrious poet, Shalom Shabazi, who was an eye-witness to these events and whose name is inscribed in the poem in acrostics. The rhyme, however, has been lost in the translation:[50]

“Tidings have reached us on the second day of [the lunar month] Rajab (i.e. corresponds with the 2nd day of the lunar month Elul), saying, ‘My companions, arise and ascribe singularity unto the Merciful One, and read [the decree] that has been inscribed! Hearken to these matters, and let not your mind be distracted, for the appointed time is at hand. Al-Mahdi the king has decreed over us that we take flight.’ The Jews of Sana'a then took leave, and have wandered unto those select places,[51] even unto the habitation of vipers and brute beasts. Even from al-Mahjam and from Dar‘ān it was decreed over us to leave; by authorization of an edict which has overcome us. Now, we shall wait in Mawza‘; there we shall dwell in the far reaches of the land belonging to the inhabitants of Arabia.

All of the inhabitants of ’Uzal (i.e. Ṣan‘ā’)[46] were obedient, and they assembled in Dhamar. My companion, tighten the camel’s gear and we’ll begin moving after the ass. Let us proceed to ‘Adinah, then to ‘Amirah, and to al-‘Ammār, while there we shall make camp. As for the young ones and those who were weak, their tears flowed like riverine brooks. ‘Idaynah, receive those who are beloved! Go out to the gate of the city to welcome them! Now is the hour of testing those who are friends. Let them take pleasure in the weary fugitive, so that his fatigue might depart from him. Lo! They are the sons of the tribes and of those who are pious; those who are highborn and of gentility.

Ṣafī al-Din (i.e. al-Mahdi) has already given the order that we not remain in our places. Whether rich man or poor man, or he that is respectable, together they have gone forth; let us proceed according to our ability, under the influences of Saturn’s horoscope; its evil portent will bring destruction. If its light flickers, it is about to change. The wisdom of the Blessed God has decreed upon the Sages of Israel, even the chosen sons of Jacob. Our elder, Suleiman [al-Naqqāsh] the Helmsman, will be the judge of those attempting to bypass [his decree]. In his hand there is the Imām’s order for all to see, while there is nothing disparaging about the matter.

I am curtailed of my sleep from dismay, while tears run down my cheeks. When our elder, al-Naqqāsh, had arrived, all of the Jews [who had come out to see him] were shaken-up. ‘Let us go out into the barren wasteland, a place of monstrous beasts and every kind of lion. Happy is he who returns safely from that place. We have already sold our fields, have forsaken our houses, and have submitted to the decree of our lord, [the king].’ The young men wept, as also the pious men, when His anger was turned against us. Consider, O Lord, and reflect upon how many distinguished men, as well as those who were delicately raised, have been humiliated!

Weep, O Rachel, in our city for [your] wandering sons! Stir up our forefathers, let them arise, standing upon their feet, so that they may make mention of our fathers who, with grace, insist upon God’s unison. May God’s favour accompany us, in whose shadow we fervently desire. Let him gather those who dwell in Yemen, seeing that He is a Shepherd and the Faithful God. We shall then hear the song of the sons of Heman (i.e. the sons of Zerah, the son of Judah). Let him then take away the poison of the adder, which is most bitter. Let him command Yinnon (i.e. the Messiah) and the Prefect [of the priest] (i.e. Elijah, the forerunner of the Messiah), and let him say to him: ‘Draw nigh!’

By the merit of our forefathers, by the favour [with which you have favoured] Levi who is of Jacob’s seed, make level [the ground] along the route in your wilderness for the son who is, both, comely and good. And by the nut tree garden may you sedate my heart which is in pain. As for Gabriel and the rooster, I have heard them in the street, whilst my pigeon is at rest; she calls out to the poor: ‘Release [them] from their bonds!’ In Zion there is to be found relief, whilst our portion is in the Garden of Eden, just as a son who is dearly loved. We shall then behold the house of our God, and the houses of Gischala (Heb. Gush Ḥalab).

The Mashtaite[52] has said: O God, remove mine affliction. Our strength is brought low in Yemen, in the days of my exile. In both small and great matters, I think about my case. Now, by the abundance [of afflictions] delights have been diminished. O gracious God! He who instructs my tongue to speak, Heaven forbid that you have forgotten me! Unto Whom belong signs and wonders. Behold, it was upon us that He bestowed His bounty, and He has chosen Moses, the son of Amram, our beloved prophet!

The pampered pigeons are cooing in the tops of the citadels. The householders of al-Sā’ilah who have come to visit al-Mahdi are complaining [before him] about how destruction and evil have come over them. They recall the conversations revolving around the Divine Law spoken [between their walls], and the vines and the flowers [in their gardens]; they recall also the social gatherings where wine was served, and the chalices, and the splendour of their wedding feasts, where [a man] would delight himself in them, become inebriated, but would avoid that which is obscene or mockery; [he’d drink] pure wine, whatever kind at hand, whose colour was as gold!

The Book of the Law (i.e. Torah) calls out to all wise men, and says: ‘Have you neglected the study of the Law? It is the reason for their ignorance. Let them repent before the masters and return unto their Lord. The day of redemption is nigh, and He shall gather together their dispersed. There is a time for drinking wine, together with [eating] dainties, and there is a time for delving in wisdom. He, whose wine makes him heavy laden, let him sleep [and rest] from his weariness and from his burden. Let him wake-up to drink a second cup, such as may be imposed upon him.

In conclusion, [let us pray] that He who is congenial (i.e. God) might conceal us in the covert of His mercy. The Benevolent One shall not forget us, while we shall proclaim the eminence of His bountiful grace. He that will console us, may he be merited with a good life. He that gives to us clothing, may his own wishes be fulfilled. My salutations go out unto those of my companions on this happy, but powerful night; [which shall continue unabated] until Venus comes out [in the sky]. That which my God has decreed shall come to pass, while for every thing there is a reason. The birds will once again trill at the top of the ben [nut] tree (Moringa peregrina) in the fruitful orchard.”

Another record of these events, composed here in poetic verse (although the rhyme has been lost in the translation), is the poem composed by Sālim ben Sa‘īd, in Judeo-Arabic. The poem is written as a nashid and is entitled, ’Ibda‘ birrub al-‘arsh (I shall commence by addressing Him who is upon the throne).[53]

"I shall commence by addressing Him who is upon the throne [of glory], even He that is an Omniscient God, the Creator of all creatures; He who causes the dumb to speak.

I was curtailed of my sleep this night, while my heart was aching on account the king's decree; he that has made a decree against us by an oath.

He has revealed his ill-intentions on a dark night, one made sullen by the shadow of death; and who has sent against us soldiers and oppressors.

We lifted up our voices unto God of heaven, [saying]: 'Remove from us the evil of this decree. Behold! You are He that governs all!'

They have destroyed all of the cities, and have cast their fear upon the Sages. There is none who takes an interest in our case, nor anyone who will take pity upon us.

He lifted up his right hand and swore, 'They have no choice but to be banished unto Mawza!'

He commanded to destroy the synagogues which were in Sana'a, the habitation of the Divine Law and the seating place of the Sages.

He forced (?) them to go out into a parched land, the Tihama and al-Mahjam.

They wandered unto Mawza‘ and walked along the paths, in the fierce blaze of heat and with severe thirst.

On the day in which he took them out of their houses, their eyes rained tears of blood. They had gone out a short distance in the dark of night.[54]

Several distinguished persons, and several disciples of the Sages [went forth into exile]; they and their little ones, who were without understanding.

'You are obliged to go forth into exile; `tis from the Lord of Heaven, who once delivered us from the hand of wicked Pharaoh.'

My heart moans over my relatives who are missing. I have no pleasure in sleep, nor in bread or water!

A flame burns inside of me, ever since the evil tidings [of the king's decree] reached me; I have become perplexed.

Praised be the Creator of the heavenly circuits, the Ruler of all [things], unto whom none can be compared.

Your covenant and your signs have been forever. You have intoxicated your people with the waters of Abraham, [made during] the covenant between the dissected halves.[55]

But now, O king of most puissant kings, your people are sadly distressed and are deprived of all things.

They (i.e. the gentiles) cast their fear upon us, while the horsemen inflict us. No one tries to help us, nor is there anyone who takes pity upon us.

They have humiliated our religion, and have called out to us to become Muslims; even to sin and to desecrate your Divine Law.

He (i.e. the Imām) has issued against us frequent declarations; shall we not fear the punishment of God on High?

Our elders have gone forth into exile by an urgent command, whether willingly or unwillingly.

I have concluded my words, my brethren! Take-up my salutations and remain silent! Our hope is in God the Omniscient.

Remember me, O God, on account of the Divine Law's hidden mystery! So, too, remember Jacob, 'the man of pure intentions' [dwelling in tents]![56]

Remember Moses who built for you the Tent of Convocation in the Sinai wilderness, on the day in which your Divine Presence dwelt thereon.

Do not forget Isaac, your bound [servant], on the day in which he spoke to Abraham face to face.

Praise be to you, O Master of the universe! `Tis from me, Sālim ben Sa‘īd, who has written rhymed verse."

Jacob Saphir's Testimony

In 1859, Lithuanian Jew, Jacob Saphir, visited the Jewish community in Yemen, less than two-hundred years after the Exile of Mawza‘, but still heard vivid accounts from the people about the things that befell their ancestors during that fateful event. Later, he made a written account of the same in his momentous ethnographic work, Iben Safir.[57] The full, unabridged account is given here (translated from the original Hebrew):

“[The Jews] dwelt securely, beneath the shadow of the kings of that country, until three-hundred (sic) years ago[58] while they were dwelling in that chief metropolis, when the daughter of the king became pregnant outside of wedlock, and they laid the blame upon a Jewish man, one of the king’s courtiers and of those who behold his countenance. However, the king’s wrath wasn’t assuaged until he had banished all of the Jews from that city and the surrounding regions, expelling them to the region of Tihama, a desolate wilderness (a walking distance of ten days’ journey in a south-westerly direction from Sana’a), between Mocha and Aden; a salty land, and one of very fearsome heat, while they were all tender and accustomed to delicacies. Many of them died along the way, while those who came there could not bear the climate of that place and its infirmities. Two thirds of them succumbed and perished, and they had entertained the notion that all of them would perish either by the plague, by famine or by thirst, may God forbid. (Here, J. Saphir brings down a poem written about the event by Rabbi Shalom Shabazi, and which has already been quoted above) Now during the time of this exile and perdition, they had lost all of their precious belongings, and their handwritten books, as well as their peculiar compositions which they possessed of old. I have also seen their synagogues and places of study used by them of old in the city of the gentiles; eternal desolations ‘and where demons will be found making sport’ (Isa. 13:21), on account of our great iniquities. Notwithstanding, it is by the mercies of the Lord that we have not perished. He (i.e. God) did not prolong the days of their exile, but sent great distempers upon the king and upon his household. (They say that this was on account of the virtue of that pious Rabbi, the kabbalist, even our teacher and Rabbi, Mori Sālim al-Shabazi, may the memory of the righteous be blessed, who brought about multiple forms of distempers upon that cruel king, who then regretted the evil [that he caused them] and sent [messengers] to call out unto them [with] a conciliatory message, [requesting] that they return to their place – with the one exception that they not dwell with them in the royal city built as a fortress. He then gave to them a possession, being a grand inheritance outside of the city, which is al-Qaʻa, B’ir al-ʻAzāb – the plain wherein is the cistern known as ʻAzāb, and they built there houses for their dwelling quarters and built for themselves an enclosing wall which extended as far as to the wall of the city built like unto a fortress. In only a short time God assisted them, and they built there a large city and one that was spacious. They also acquired wealth and they rose to prominence, while many of the villagers likewise seized [upon land] with them, that they might dwell in the city, until it became [a place] full of people. At that time, Mori Yiḥya Halevi was the Nasi among them and the Exilarch.)”

References to Sana'a before the expulsion

There are several references to Jewish life in Sana'a before the expulsion of 1679. Maharitz (d. 1805) mentions in his Responsa[59] that before the Exile of Mawza the Jews of Sana'a had an old custom to say the seven benedictions for the bridegroom and bride on a Friday morning, following the couple's wedding the day before. On Friday (Sabbath eve) they would pitch a large tent within a garden called al-Jowzah, replete with pillows and cushions, and there, on the next day (Sabbath afternoon), the invited guests would repeat the seven benedictions for the bridegroom and bride, followed by prayer inside the tent, before being dismissed to eat of their third Sabbath meal, at which time some accompanied the bridegroom to his own house to eat with him there. The significance of this practice, according to Maharitz, was that they made the seven blessings even when not actually eating in that place, a practice which differs from today's custom.[59]

German-Jewish ethnographer, Shelomo Dov Goitein, mentions a historical note about the old synagogue in Sana'a, before the expulsion of Jews from the city in 1679, and which is written in the glosses of an old copy of the Mishnah (Seder Moed), written with Babylonian supralinear punctuation.[60] The marginal note concerns the accurate pronunciation of the word אישות in Mishnah Mo'ed Ḳaṭan 1:4, and reads as follows: "Now the Jews of Sana'a read it as אִישׁוּת (ishūth), with a [vowel] shuraq (shuruk). I studied with them a long time ago, during the time when the synagogue of Sana'a was still standing on its site."[60]

Enactments in wake of exile (1680–1690)

Upon returning to Sana’a, the Chief Rabbis, led by R. Shelomo Manzeli and Yiḥya Halevi (called Alsheikh), came together in the newly built Alsheikh synagogue and decided to put in place a series of enactments meant at bettering the spiritual condition of the community, and which they hoped would prevent the recurrence of such harsh decrees against the Jewish community in the future.[61] These enactments were transcribed in a document entitled Iggereth Ha-Besoroth (Letter of Tidings), and which was believed to have been disseminated amongst the community at large. Only excerpts of the letter have survived.[62] The enactments called out for a more strict observance of certain laws which, heretofore, had been observed with leniency. Such strictures were to be incumbent upon the entire community and which, in the Rabbis’ estimation, would have given to the community some merit in the face of oppression or persecution. Not all of these enactments, however, were upheld by the community, since some enactments were seen as breaking-away from tradition.[63]

Further reading

- Yemenite Authorities and Jewish Messianism - Aḥmad ibn Nāṣir al-Zaydī's Account of the Sabbathian Movement in Seventeenth Century Yemen and its Aftermath, by P.S. van Koningsveld, J. Sadan and Q. Al-Samarrai, Leiden University, Faculty of Theology 1990

- A history of Arabia Felix or Yemen, from the commencement of the Christian era to the present time : including an account of the British settlement of Aden / by R.L. Playfair, Salisbury, N.C. : Documentary Publications 1978

- My Footsteps Echo - The Yemen Journal of Rabbi Yaakov Sapir, edited and annotated by Yaakov Lavon, Jerusalem 1997

- Jewish Domestic Architecture in San'a, Yemen, by Carl Rathjens (see Appendix: Seventeenth Century Documents on Jewish Houses in San'a - by S.D. Goitein), Israel Oriental Society: Jerusalem 1957, pp. 68–75[64]

- Chapters in the Heritage of Yemenite Jewry Under the Influence of Shulhan Arukh and the Kabbalah of R. Yitzhaq Luria, by Aharon Gaimani, Ramat-Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press 2005, pp. 145–158 (Hebrew)

- Yemenite Jewry: Origins, Culture and Literature, by Rueben Aharoni, Bloomington: Indiana University Press 1986, pp. 121–135

External links

- The Exile of Mawza, by Dr. Aharon Gaimani of Bar-Ilan University

- Sefunot, Volume 2, Jerusalem 1958, pages רמו-רפו (pp. 254–294 in PDF) (Hebrew)

- The Mawza Exile at the Juncture of Zaydi and Ottoman Messianism, via JSTOR (registration required)

References

- ↑ Yehudah Ratzaby, Galut Mawzaʻ, Sefunot (Volume Five), Ben-Zvi Institute: Jerusalem 1961, p. 339 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Yosef Qafiḥ (ed.), “Qorot Yisra’el be-Teman by Rabbi Ḥayim Ḥibshush,” Sefunot, Volume 2, Ben-Zvi Institute: Jerusalem 1958, pp. 246-286 (Hebrew); Yosef Qafiḥ, Ketavim (Collected Papers), Vol. 2, Jerusalem 1989, p. 714 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Yosef Tobi, Politics and Poetry in the Works of Shalom Shabazī, Routledge - Israel Affairs 2014, p. 6

- ↑ One Jewish poet bewails their fate at this time, saying: "Since the day that they removed the turbans from our heads (i.e. 1666), we are full of orders which he decrees [against us]. He has placed over our heads [a governor] who is the master of oppression!" See: Ratzaby, Sefunot (Volume Five), Jerusalem 1961, p. 378 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Yosef Tobi, Politics and Poetry in the Works of Shalom Shabazī, Routledge - Israel Affairs 2014, p. 7

- ↑ Yosef Tobi, The Jews of Yemen (Studies in Their History and Culture), Brill: Leiden 1999, pp. 77-79

- ↑ Tanḥum ben Joseph, of Jerusalem, al-Murshid al-kāfi (in manuscript form), p. 112 (Yosef Tobi’s Private Collection), we read the following marginal note: “The synagogue was destroyed here, [in] Ḥamdah, on Wednesday, the 17th day of the lunar month Teveth, in the year 1,989 [of the Seleucid Era] (=1678 CE), by order of al-Mahdi and Muhammad ben Ahmad.” Yehudah Ratzaby (1984, p. 149) also brings down a manuscript extracted from the binding of an old book, now at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York (239), in which the author complains: "The razing of the synagogue of Būsān on the fourth day of the week which is the third day of the year 1,989 [of the Seleucid Era] (= 1678 CE), and the enemies forbade us to gather as a quorum of ten for prayer and three scrolls of Law were slashed to pieces. May He in His mercy save us and all Israel from all the decrees." (See: Yosef Tobi, The Jews of Yemen - Studies in Their History and Culture, Brill: Leiden 1999, pp. 78 [end] - 79)

- ↑ Yosef Qafiḥ (ed.), “Qorot Yisra’el be-Teman by Rabbi Ḥayim Ḥibshush,” Sefunot, Volume Two, Jerusalem 1958, page רסב (p. 270 in PDF) (Hebrew); Yosef Qafiḥ, Ketavim (Collected Papers), Vol. 2, Jerusalem 1989, p. 713 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Yosef Qafiḥ (ed.), “Qorot Yisra’el be-Teman by Rabbi Ḥayim Ḥibshush,” Sefunot, Volume Two, Jerusalem 1958], page רסג (Hebrew); Yosef Qafiḥ, Ketavim (Collected Papers), Vol. 2, Jerusalem 1989, p. 714 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Yosef Tobi, Studies in ‘Megillat Teman’ (ʻIyunim bi-megilat Teman), The Magnes Press – Hebrew University, Jerusalem 1986, p. 42, note 68 (Hebrew).

- ↑ Yiḥya Saleḥ, Tiklāl Etz Ḥayim Hashalem (ed. Shimon Saleh), vol. 1, Jerusalem 1971, s.v. Shaḥrith shel Shabbath. Rabbi Shelomo ben Saadia al-Manzeli (1610–1690) is said to have returned to his post after the Mawza Exile, serving as both President of the court at Ṣan‘ā’ and the city's spiritual instructor. He helped draft a series of enactments meant at bettering the spiritual condition of the Jewish community, by way of merit, and thereby hoping to prevent the recurrence of harsh decrees against the community in the future. See: Moshe Gavra, Meḥqarim basiddurei tayman: Studies in the Prayer Books of Yemen, vol. 1, Benei Barak 2010, p. 70 (Hebrew).

- ↑ Rabbi Yosef Qafih believes that they were given advance warning as early as late-summer of 1678. See: Yosef Qafiḥ (ed.), “Qorot Yisra’el be-Teman by Rabbi Ḥayim Ḥibshush,” Ketavim (Collected Papers), Vol. 2, Jerusalem 1989, p. 713, note 130 (Hebrew). According to Arabic sources, Imām al-Mahdī had ordered the newly appointed governor of Sana'a, Muhammad ibn al-Mutawakkil, to expel the Jews and demolish their synagogues on 1 Shaʻbān 1088 anno Hijri (= 29 September 1677), nearly two years before the actual expulsion. The matter was delayed only because the governor wished to consult first with the religious scholars of his city. All this may have been done without the foreknowledge of the Jewish community. (See: Yemenite Authorities and Jewish Messianism, by P.S. van Koningsveld, J. Sadan and Q. Al-Samarrai, Leiden University 1990, p. 23)

- ↑ Yosef Qafiḥ (ed.), “Qorot Yisra’el be-Teman by Rabbi Ḥayim Ḥibshush,” Ketavim (Collected Papers), Vol. 2, Jerusalem 1989, p. 714 (Hebrew)

- ↑ In accordance with a teaching in Leviticus 22:31–32, and explained in the Responsa of Rabbi David ibn Zimra,vol. 2 (part 4), responsum no. 92 [1163], Warsaw 1882 (reprinted), p. 47 (Hebrew pagination כד). Here, the author makes it clear that if Jews are collectively compelled by the Ismaelites to convert to Islam or else face punishment, they are to prefer punishment rather than exchange their religion for another, and, in so doing, they bring sanctity to God's name.

- ↑ Avraham al-Naddaf, Ḥoveret (article: History of Rabbi Sholem al-Shabazi), Jerusalem 1928 (Hebrew); Reprinted in Zechor le’Avraham, by Uziel al-Nadaf, (Part II) Jerualem 1992 (Hebrew), pp. 4-5

- ↑ Yosef Qafiḥ (ed.), “Qorot Yisra’el be-Teman by Rabbi Ḥayim Ḥibshush,” Ketavim (Collected Papers), Vol. 2, Jerusalem 1989, p. 714 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Yehudah Ratzaby, Sefunot (Volume Five), his article: Galut Mawza‘, Ben-Zvi Institute: Jerusalem 1961, p. 367, s.v. poem entitled: אבן אלאסבאט אבדע, lines 16–19 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Yehudah Ratzaby, Sefunot (Volume Five), his article: Galut Mawza‘ , Ben-Zvi Institute: Jerusalem 1961, p. 369, s.v. poem entitled: אבן אלאסבאט אבדע, lines 4–5 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Yehudah Ratzaby, Zion – A Quarterly for Research in Jewish History, vol. xxxvii. The Historical Society of Israel: Jerusalem 1972, pp. 203-207 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Hebrew expression of contriteness, signifying the people’s acceptance of God’s judgments and which expression is based on the Jewish teaching that all of God’s ways are just.

- ↑ Yehudah Ratzaby, Zion – A Quarterly for Research in Jewish History, vol. xxxvii. The Historical Society of Israel: Jerusalem 1972, p. 207 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Yosef Qafiḥ (ed.), “Qorot Yisra’el be-Teman by Rabbi Ḥayim Ḥibshush,” Sefunot (Volume Two), Ben-Zvi Institute: Jerusalem 1958, pp. 246–286 (Hebrew); Yosef Qafiḥ, Ketavim (Collected Papers), Vol. 2, Jerusalem 1989, pp. 714–715 (Hebrew)

- ↑ David Solomon Sassoon, On the Origins of the Jews in Yemen (לקורות היהודים בתימן), Budapest 1931, p. 6

- ↑ Yosef Qafiḥ (ed.), “Qorot Yisra’el be-Teman by Rabbi Ḥayim Ḥibshush,” Ketavim (Collected Papers), Vol. 2, Jerusalem 1989, p. 716 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Yosef Qafiḥ (ed.), “Qorot Yisra’el be-Teman by Rabbi Ḥayim Ḥibshush,” Ketavim (Collected Papers), Vol. 2, Jerusalem 1989, p. 714 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Yosef Tobi (ed.), Studies in ‘Megillat Teman’ by Yiḥyah Salaḥ, The Magnes Press: Hebrew University, Jerusalem 1986, pp. 44-47 (based on MS. #1, Hebrew)

- ↑ Professor Yosef Tobi says that the date here is in error, and should rather be amended to read 1679.

- ↑ This reading, based on the sequence of the biblical portions that are read throughout the year, would have been read the following year, in 1680.

- ↑ Yosef Qafiḥ (ed.), “Qorot Yisra’el be-Teman by Rabbi Ḥayim Ḥibshush,” Sefunot, Volume 2, 1958, pp. 246-286 (Hebrew); Yosef Qafiḥ, Ketavim (Collected Papers), Vol. 2, Jerusalem 1989, p. 706 (Hebrew)

- ↑ R. Serjeant & R. Lewcock, San'a'; An Arabian Islamic City. London 1983, p. 82; R.L. Playfair, A History of Arabia Felix or Yemen. Bombay 1859, p. 112; N.A. Stillman, The Jews of Arab Lands. Philadelphia 1979, p. 322.

- ↑ Yosef Qafiḥ, Halikhot Teiman (Jewish Life in Sana) , Ben-Zvi Institute, Jerusalem, 1982, p. 80, note 44

- ↑ Yosef Tobi, Studies in `Megillat Teman`, Jerusalem 1986, p. 77 (Hebrew) ISBN 965-223-624-1

- ↑ Yosef Qafiḥ (ed.), “Qorot Yisra’el be-Teman by Rabbi Ḥayim Ḥibshush,” Ketavim (Collected Papers), Vol. 2, Jerusalem 1989, p. 706 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Yosef Qafiḥ (ed.), “Qorot Yisra’el be-Teman by Rabbi Ḥayim Ḥibshush,” Ketavim (Collected Papers), Vol. 2, Jerusalem 1989, pp. 706-707 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Yosef Qafiḥ (ed.), “Qorot Yisra’el be-Teman by Rabbi Ḥayim Ḥibshush,” Ketavim (Collected Papers), Vol. 2, Jerusalem 1989, pp. 706 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Shelomo Dov Goitein, The Yemenites (History, Communal Organization, Spiritual Life), Ben-Zvi Institute: Jerusalem 1983, p. 162 (Hebrew). David Solomon Sassoon attributes the writing to [the son of] Sa‘īd, based on the author’s own remark that he is “the son of Ḥazmaq the younger” (= Sa‘īd, or Se‘adyah), the usual rendition for this name given in the reversed order of the Hebrew alphabet. See: David Solomon Sassoon, Ohel Dawid (vol. 2), Oxford University Press: London 1932, p. 969, s.v. דופי הזמן. A microfilm copy of this work is available at the National Library of Israel in the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (Givat Ram Campus), Manuscript Dept., Microfilm reel # F-9103.

- ↑ Yosef Qafiḥ (ed.), “Qorot Yisra’el be-Teman by Rabbi Ḥayim Ḥibshush,” or what was originally entitled Dofi Hazeman (Vicissitudes of Time), Sefunot (Volume Two), 1958, pp. 246-286 (Hebrew); Yosef Qafiḥ, Ketavim (Collected Papers), Vol. 2, Jerusalem 1989, p. 716 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Carsten Niebuhr, Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern (Description of Travel to Arabia and Other Neighboring Countries), Zürich 1992, pp. 416-418 (German)

- ↑ Hermann Burchardt, Die Juden in Yemen, published in: Ost und West, Berlin 1902, p. 338 (German).

- ↑ Carl Rathjens & Hermann v. Wissman, Landeskundliche Ergebnisse, vol. 40, Hamburg 1934, pp. 133-134; 141 (German).

- ↑ P.S. van Koningsveld, J. Sadan & Q. Al-Samarrai, Yemenite Authorities and Jewish Messianism, Leiden University 1990, pp. 156-158. ISBN 9071220079

- ↑ Amram Qorah, Sa‘arat Teman (2nd edition), Jerusalem 1988, pp. 10-11 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Amram Qorah, Sa‘arat Teman (1st edition), Jerusalem 1954, pp. 10-11 (pp. 23-24 in PDF) [Hebrew]

- ↑ Amram Qorah, Sa‘arat Teman (2nd edition), Jerusalem 1988, pp. 9 -10 (Hebrew). Moshe Gavra brings down the same account, mentioning that Rabbi Pinheas ben Gad Hacohen of Dhamar had first written this account in a Siddur that he had written for Rabbi Yehudah Ṣa'adi in 1680. See: Gavra, Moshe (2010). Meḥqarim basiddurei tayman: Studies in the Prayer Books of Yemen, vol. 1, p. 72 (in Hebrew). Benei Barak: Mechon le'ḥeqer ḥakhmei tayman.

- 1 2 Sefer Hashirim Hagadol – The Large Song Book, Shalom Shabazi (ed. Yosef Hasid), Jerusalem 1976, p. 51, s.v. אזיל דמעותי כמטר יזלו (Hebrew)

- 1 2 Based on Rabbi Saadia Gaon's Judeo-Arabic translation of ’Uzal in Genesis 10:27, which is rendered as Sanaa.

- ↑ An allusion to Ishmael, the son of Hagar (handmaid of Abraham), and the progenitor of the Arab nation.

- ↑ Based on Rabbi Saadia Gaon's Judeo-Arabic translation of Hadoram in Genesis 10:27, which is rendered as Dhamar.

- ↑ An allusion to the tablets of the Ten Commandments, given to the people of Israel while they were gathered at Mount Sinai.

- ↑ The English translation (in the collapsible thread) is based on the Hebrew translation of the poem made by Yehudah Ratzaby, in his article, Galut Mawza‘, published in Sefunot, Volume 5, Ben-Zvi Institute: Jerusalem 1961, pp. 353-354 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Lit. "...have wandered unto Khabt," perhaps being the Al-Khabt in the Abyan District, in the far south-eastern reaches of Yemen, near the Indian Ocean. Yehudah Ratzaby suggests that the sense here is the two towns, the one being called Khabt of Darʻān and the other, Khabt of al-Baqr. Initially, the king had agreed that Jews be permitted to resettle in these towns, but later changed his mind. See: Yehudah Ratzaby, article: Galut Mawza‘, published in Sefunot (Volume Five), Ben-Zvi Institute: Jerusalem 1961, pp. 378-379, note *4 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Another appellation for Shalom Shabazi

- ↑ Yehudah Ratzaby, Sefunot (Volume Five), his article: Galut Mawza‘, Ben-Zvi Institute: Jerusalem 1961, pp. 379-380 (Translation of the original Judeo-Arabic), s.v. poem entitled: אבדע ברב אלערש; The original Judeo-Arabic was published in Hazofeh – Quartalis Hebraica (ed. Dr. L. Blau), vol. 7, Budapest 1923; (ibid.) Second edition, Jerusalem 1972, pp. 2–3. The original Judeo-Arabic text can also be had at the Hebrew University National Library (Givat Ram Campus), Jerusalem, Manuscript Dept., Microfilm reel # F-9103.

- ↑ In accordance with a verse in Ezekiel 12:4, And you shall go forth at eventide in their sight, as they that go forth into exile.

- ↑ An allusion to Genesis 15:1-21.

- ↑ An allusion to Genesis 25:27.

- ↑ Jacob Saphir, Iben Safir (vol. 1 - ch. 43), Lyck 1866, pp. 100a-100b (Hebrew)

- ↑ Should be amended to read “approximately two-hundred years ago,” i.e. 1679

- 1 2 Questions & Responsa Pe'ulath Ṣadiq, Yihya Saleh, vol. III, responsum # 252, Jerusalem 1979, p. 153 (Hebrew)

- 1 2 The Mishnah: Order Mo'ed - A Yemenite Manuscript , ed. Yehudah Levi Nahum, Introduction, Ḥolon 1975, p. 18 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Moshe Gavra, Meḥqarim basiddurei tayman: Studies in the Prayer Books of Yemen, vol. 1, Benei Barak 2010, pp. 70 – 71; ibid. vol. 4, pp. 156 – 159 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Rabbi Yosef Subeiri, Siddur Kenesseth Ha-Gedolah, vol. 3, Tel-Aviv/Jaffa 1976 – 1992, p. 297 (Hebrew); Rabbi Yihya Saleh, Questions & Responsa Pe'ulath Ṣadiq, vol. III, responsum # 252, Jerusalem 1979, p. 153 (Hebrew)

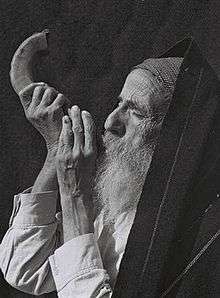

- ↑ One of the enactments called out for making one-hundred blasts of the horn on the Jewish New Year (Rosh Hashanah), based on a teaching found in Rabbi Nathan ben Jehiel’s Sefer Ha-Arukh, s.v. ערב, instead of the traditional forty blasts which had been observed earlier. Another enactment sought to make it a standard procedure during the Mussaf-prayer of Rosh Hashanah to make two prayers: the first, by the congregation praying silently, followed by a repetition of the prayer said aloud by the Shaliach Tzibbur (Prayer precentor). Maharitz would later adamantly oppose the enactment, since it sought to cancel the ancient tradition in Yemen in this regard in which it had always been a practice to make only one Mussaf-prayer. Another enactment concerned the seven benedictions mentioned by Rabbi Yosef Karo in his Shulḥan Arukh (Even Haʻezer 62:10), where he brings down a certain opinion which states that is not permissible for the groom and bride to be entertained in another person’s house other than in his own house during the seven days of wedding festivities, unless he and his bride were to leave their own house or town for an extended period of time, in which case it is then permissible. The enactment is mentioned with regard to Iggereth Ha-Besoroth in Maharitz’s Questions & Responsa, Pe'ulath Sadiq, vol. III, responsum # 252, although the enactment seemed to have been rejected by Maharitz, in favour of Israel’s older practice in Yemen. Rabbi Shalom Yitzhaq Halevi informs us that the Yemenite custom in his day was as that taught by Maharitz, and rectifies the discrepancy between the Shulḥan Arukh and the Yemenite Jewish custom by writing in the glosses of his 1894 edition of the Tiklāl Etz Ḥayim that the Shulḥan Arukh (ibid.) refers merely to when the groom and bride are invited to make the “seven benedictions” in another house where, during the seven days of feasting, a supper had been made on behalf of a circumcision, or some other ceremonial meal other than what was specifically made on the groom's behalf, in which it is not permitted to say for them the “seven benedictions.” See also Rabbi Ḥayim Kessar's Questions & Responsa Haḥayim wehashalom (Even Haʻezer, responsum # 10), who cites from Rabbi Yihya Hacohen’s Responsa, Ḥayei Shalom (responsum # 2), where he says that after the wedding, it was never a custom in Yemen that a man's bride accompanied him when he was invited to eat in the home of others. He reasons that, since she is not with him, they should not say the seven benedictions for the bridegroom alone.

- ↑ The Appendix treats on ancient Jewish houses in San'a before the expulsion of Jews from the city, based on five legal deeds of sale drawn up before 1679, and proves beyond doubt that the newer houses in the new Jewish Quarter were built according to exactly the same plan as those in their former settlement.