European Public Prosecutor

| European Union |

This article is part of a series on the |

Policies and issues

|

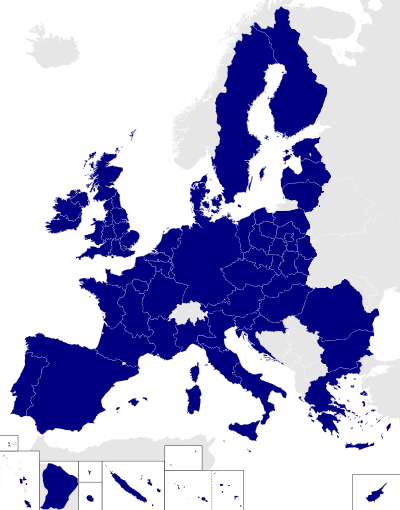

The European Public Prosecutor is a proposed post in the European Union that can be established under the Treaties as amended by the Treaty of Lisbon.

Treaty

The Public Prosecutor was inserted as article 86 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union by the Treaty of Lisbon.[1][2] The article states the following:

- Establishment;

- The Council of the European Union, by a special legislative procedure, may establish a European Public Prosecutor's Office on the basis of Eurojust.

- This must be done by unanimity in the Council and with the consent of the European Parliament

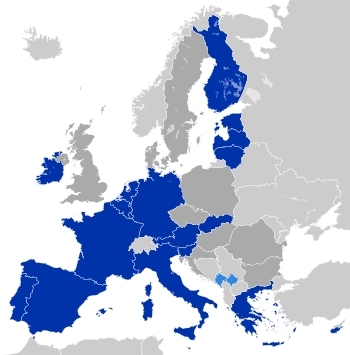

- If the Council cannot reach unanimity, a group of at least nine member states may refer a draft to the European Council.

- Those member states may also proceed to establish enhanced co-operation between themselves after informing Parliament, the Council and the Commission.

- Role;

- The office shall, in liaison with Europol, be responsible for investigating, prosecuting and bringing to judgment those connected to offences against the EU's financial interests.

- It shall exercise this function in the relevant national courts.

- The regulations establishing the office shall determine rules governing how it performs its duties including the admissibility of evidence.

- The European Council may amend the treaty, after consulting the Commission and gaining the consent of Parliament, to extend its powers to include serious cross border crime

Proposals

It was strongly backed by the former Commissioner for Justice, Freedom and Security, Franco Frattini as part of plans to strengthen the Eurojust agency. Frattini stated in August 2007 that he is "convinced that Europe will have its general prosecutor in the future" and suggested that the Commission was just waiting for the treaty to come into force. He stated that a prosecutor "could prove useful" in areas "where important European interests are at stake", namely in dealing with financial crime, fraud and counterfeiting at European level.[3]

The firm, in late 2007, the Lisbon Treaty by all Member States of the European Union, which refers explicitly to the idea of creating a European Public Prosecutor to combat crimes affecting the financial interests of the Union and, where appropriate, to combat serious crime with cross-border dimension, resulted in the conclusion of an International Seminar in Madrid to study the new institution and the possibilities of its implementation. The Seminar was called by the Spanish Attorney General Cándido Conde-Pumpido, and led by Prosecutors Jorge Espina and Isabel Vicente Carbajosa. The presentations, discussions and conclusions of the meeting were collected in a book, "The future European Public Prosecutor's Office", in English and Spanish, and have served to date guide to the proposals and jobs that have been carried out on the implementation of this Institution.[4]

Following the short selling of certain euro-zone financial products in 2009 and 10, Spain proposed the EU enact the European Public Prosecutor provision so the post could co-ordinate legal action in retaliation. "Spain wants the European Union to use a planned public prosecutor's office for the region to protect the euro currency against speculators", Spanish attorney general Cándido Conde-Pumpido said in March 2010. [5]

In March 2010 Eurojust cited the European Public Prosecutor's Office as a potential solution to the problem of cross border crime in the EU. Despite opposition from some member states seeing it as impinging on their sovereignty (partly due to the necessary harmonisation of legal codes) Eurojust set up a working group to study the idea.[6]

Spanish Presidency draft for the implementation of the EPPO

The Spanish Attorney General Cándido Conde-Pumpido, officially launched in Brussels, in March 2010, on Spanish Presidency draft for the implementation of the European Prosecutor, pursuant to the provision of Article 86 of the Treaty of Lisbon. Conde-Pumpido, speaking with the President of the Commission of Justice and Home Affairs of the European Parliament, Juan Fernando López Aguilar, and the Spanish State Secretary for the European Union (EU), Diego Lopez Garrido, presented a technical project, developed from the conclusions of the International Conference convened by the Spanish Prosecutor in 2008 and 2009, which would be discussed later in the Luxembourg Council.

The creation of this institution was subsequently discussed, according to the Spanish proposal, by the meeting of Ministers of Justice and Home Affairs held in Luxembourg on 27 April 2010, but its implementation was suspended until a new discussion in 2013. [7]

Seminar of the Belgian Presidency and Eurojust in Bruges

On 21 and 22 September 2010, Eurojust, in co-operation with the Belgian Presidency of the Council of the European Union, held a strategic seminar, "Eurojust and the Lisbon Treaty: towards more effective action", "Establishment of the European Public Prosecutor's Office from Eurojust?", at the College of Europe in Bruges, Belgium.

The goals of the seminar were the development of Eurojust in light of the Lisbon Treaty and the possible establishment of a European Public Prosecutor's Office from Eurojust under Article 86 TFEU.[8]

New Proposals

The European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso said on 12 September 2012 in his speech to the European Parliament on the state of the Union, the next presentation of a proposal for the creation of a European Public Prosecutor, based on "commitment to uphold the rule of law ".

On 17 July 2013 the European Commission, at the initiative of Vice-President Viviane Reding and Commissioner Algirdas Semeta made proposal for the establishment of a, European Public Prosecutor's Office (EPPO).[9][10]

The proposal will now be discussed by the representatives of the EU Member States' experts under the specific procedure set by Article 86 of the Treaty

The following 3 main options may be considered within the range of options concerning the scope of the initiative: · Doing nothing – criminal investigations of PIF offences are (still) conducted by Member State authorities exclusively; · Setting-up the EPPO with a limited mandate (PIF offences) – EPPO has priority competence to order investigations and direct prosecutions into PIF offences · Setting up the EPPO with an extended mandate (PIF offences and serious cross-border crimes) –- EPPO has exclusive/shared competence to order investigations and direct prosecutions into PIF offences and other serious cross-border crimes (money laundering, corruption, accounting offences.

Besides these 3 options regarding scope, the Commission will need to consider a series of significant legal, institutional and organisational matters (relationship with Eurojust, OLAF, national authorities, judicial review) which could be formulated as sub-options. Moreover, particular procedural issues (EP involvement, legislativeprocess, if unanimity requirements is not met, enhanced co-operation with which member States, etc.) should be considered in these options. In accordance with Art.86 the proposal could include one or more regulations covering different aspects of the setting up of an EPPO. Soft law instruments are not relevant as legislative measures are needed to address criminal offences and law enforcement.

Likely impacts will include a more effective, dissuasive and equivalent criminal law protection of the Union's financial interests. Irregularities affecting the European budget may reach or exceed 1 Billion Euro per year, from which around 280 Million Euro could be suspected EU-fraud cases to be investigated within the EPPO's competence.. This amount could be significantly reduced if the EPPO were to direct investigations and prosecutions throughout the EU, acting on all cases of PIF offences. Moreover, economies of scale might be achieved for the benefit of justice budgets of Member States, due to a streamlining of the judicial procedures involving EU financial interests across the EU.

Depending on how the relationship between the EPPO and the national authorities will be defined the impact will be primarily on national police and judicial authorities, which will certainly have to cope with the new framework for investigations and prosecutions ordered by the EPPO. The administrative burden depends on the new relations established between the EPPO and the national authorities and whether the initiative will impose new information obligations on MS.

Preparatory work, in particular the 2001 Green paper on the establishment of a European Prosecutor will be taken into consideration. Existing studies and evaluations, in particular the Criminal Justice Systems Study, the Euroneeds Study, the Pretrial investigative model rules, the Spanish Presidency Report, officially launched in Brussels in March 2010, etc. and studies regarding Eurojust, will provide valuable input.

National and European Parliaments

In November 2013 the Commission indicated its intention to go ahead with the establishment of a European Public Prosecutor, despite the opposition of 14 EU national parliaments.[11] The European Parliament has subsequently voted in favour of the Commission's proposal to set up the office.<ref name=European Parliament backs European Public Prosecutor's office>"European Parliament backs European Public Prosecutor's office". out-law.com. 14 March 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2014.</ref>

See also

References

- ↑ eur-lex

- ↑ eur-lex

- ↑ Brussels eyes single European public prosecutor, Goldirova, Renata (1 August 2007).EU Observer

- ↑ The Future European Prosecutor's Office book

- ↑ Spain calls for EU prosecutor to protect euro, Reuters

- ↑ Eurojust

- ↑ España insiste en la Fiscalia Europea. Diario jurídico, 7 de mayo de 2010 (Spanish)

- ↑ Strategic Seminar – Establishment of the European Public Prosecutor's Office from Eurojust?

- ↑ Brussels explores creation of EU public prosecutor.

- ↑ http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-13-709_en.htm

- ↑ "'YELLOW CARD' ON EPPO TRIGGERS COMMISSION REVIEW". Vice President of the European Commission. November 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2014.