Euler's Disk

Euler's Disk is a scientific educational toy, used to illustrate and study the dynamic system of a spinning disk on a flat surface (such as a spinning coin), and has been the subject of a number of scientific papers.[1] The apparatus is known for a seemingly paradoxical dramatic speed-up in spin rate as the disk loses energy and approaches a stopped condition. This phenomenon is named for Leonhard Euler, who studied it in the 18th century.

Components and use

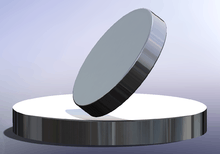

The commercially available toy consists of a heavy, thick chrome-plated steel disk and a rigid, slightly concave, mirrored base. Included holographic magnetic stickers can be attached to the disk, to enhance the visual effect of "sprolling" or "spolling" (spinning/rolling), but these attachments are strictly decorative. The disk, when spun on a flat surface, exhibits a spinning/rolling motion, slowly progressing through different rates and types of motion before coming to rest—most notably, the precession rate of the disk's axis of symmetry accelerates as the disk spins down. The rigid mirror is used to provide a suitable low-friction surface, with a slight concavity which keeps the spinning disk from "wandering" off a support surface.

An ordinary coin spun on a table, as with any disk spun on a relatively flat surface, exhibits essentially the same type of motion, but is normally more limited in the length of time before stopping. The commercially available Euler’s Disk toy provides a more effective demonstration of the phenomenon than more commonly found items, having an optimized aspect ratio and a precision polished, slightly rounded edge to maximize the spinning/rolling time.

Physics

A spinning/rolling disk ultimately comes to rest, and it does so quite abruptly, the final stage of motion being accompanied by a whirring sound of rapidly increasing frequency. As the disk rolls, the point of rolling contact describes a circle that oscillates with a constant angular velocity . If the motion is non-dissipative (frictionless), is constant, and the motion persists forever; this is contrary to observation, since is not constant in real life situations. In fact, the precession rate of the axis of symmetry approaches a finite-time singularity modeled by a power law with exponent approximately −1/3 (depending on specific conditions).

There are two conspicuous dissipative effects: rolling friction when the coin slips along the surface, and air drag from the resistance of air. Experiments show that rolling friction is mainly responsible for the dissipation and behavior[2]—experiments in a vacuum show that the absence of air affects behavior only slightly, while the behavior (precession rate) depends systematically on coefficient of friction. In the limit of small angle (i.e. immediately before the disk stops spinning), air drag (specifically, viscous dissipation) is the dominant factor, but prior to this end stage, rolling friction is the dominant effect.

History of research

Moffatt

In the early 21st century, research was sparked by an article in the April 20, 2000 edition of Nature,[3] where Keith Moffatt showed that viscous dissipation in the thin layer of air between the disk and the table would be sufficient to account for the observed abruptness of the settling process. He also showed that the motion concluded in a finite-time singularity. His first theoretical hypothesis was contradicted by subsequent research, which showed that rolling friction is actually the dominant factor.

Moffatt showed that, as time approaches a particular time (which is mathematically a constant of integration), the viscous dissipation approaches infinity. The singularity that this implies is not realized in practice, because the magnitude of the vertical acceleration cannot exceed the acceleration due to gravity (the disk loses contact with its support surface). Moffatt goes on to show that the theory breaks down at a time before the final settling time , given by:

where is the radius of the disk, is the acceleration due to Earth's gravity, the dynamic viscosity of air, and the mass of the disk. For the commercially available Euler’s Disk toy (see link in "External links" below), is about seconds, at which time the angle between the coin and the surface, , is approximately 0.005 radians and the rolling angular velocity, , is about 500 Hz.

Using the above notation, the total spinning/rolling time is:

where is the initial inclination of the disk, measured in radians. Moffatt also showed that, if , the finite-time singularity in is given by

Experimental results

Moffatt's theoretical work inspired several other workers to experimentally investigate the dissipative mechanism of a spinning/rolling disk, with results that partially contradicted his explanation. These experiments used spinning objects and surfaces of various geometries (disks and rings), with varying coefficients of friction, both in air and in a vacuum, and used instrumentation such as high speed photography to quantify the phenomenon.

In the 30 November 2000 issue of Nature, physicists Van den Engh, Nelson and Roach discuss experiments in which disks were spun in a vacuum.[4] Van den Engh used a rijksdaalder, a Dutch coin, whose magnetic properties allowed it to be spun at a precisely determined rate. They found that slippage between the disk and the surface could account for observations, and the presence or absence of air only slightly affected the disk's behavior. They pointed out that Moffatt's theoretical analysis would predict a very long spin time for a disk in a vacuum, which was not observed.

Moffatt responded with a generalized theory that should allow experimental determination of which dissipation mechanism is dominant, and pointed out that the dominant dissipation mechanism would always be viscous dissipation in the limit of small (i.e., just before the disk settles).[5]

Later work at the University of Guelph by Petrie, Hunt and Gray[6] showed that carrying out the experiments in a vacuum (pressure 0.1 pascal) did not significantly affect the energy dissipation rate. Petrie et al. also showed that the rates were largely unaffected by replacing the disk with a ring shape, and that the no-slip condition was satisfied for angles greater than 10°.

On several occasions during the 2007–2008 Writers Guild of America strike, talk show host Conan O'Brien would spin his wedding ring on his desk, trying to spin the ring for as long as possible. The quest to achieve longer and longer spin times led him to invite MIT professor Peter Fisher onto the show to experiment with the problem. Spinning the ring in a vacuum had no identifiable effect, while a Teflon spinning support surface gave a record time of 51 seconds, corroborating the claim that rolling friction is the primary mechanism for kinetic energy dissipation.

See also

- List of topics named after Leonhard Euler

- Tippe top - another simple physics toy that exhibits surprising behavior

References

- ↑ "Publications". eulersdisk.com.

- ↑ Easwar, K.; Rouyer, F.; Menon, N. (2002). "Speeding to a stop: The finite-time singularity of a spinning disk". Physical Review E. 66 (4). Bibcode:2002PhRvE..66d5102E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.66.045102.

- ↑ Moffatt, H. K. (20 April 2000). "Euler's disk and its finite-time singularity". Nature. 404 (6780): 833–834. doi:10.1038/35009017. PMID 10786779.

- ↑ Van den Engh, Ger; Nelson, Peter; Roach, Jared (30 November 2000). "Analytical dynamics: Numismatic gyrations". Nature. 408 (6812): 540. Bibcode:2000Natur.408..540V. doi:10.1038/35046209.

- ↑ Moffatt, H. K. (30 November 2000). "Reply: Numismatic gyrations". Nature. 408 (6812): 540. Bibcode:2000Natur.408..540M. doi:10.1038/35046211.

- ↑ Petrie, D.; Hunt, J. L.; Gray, C. G. (2002). "Does the Euler Disk slip during its motion?". American Journal of Physics. 70 (10): 1025–1028. Bibcode:2002AmJPh..70.1025P. doi:10.1119/1.1501117.

External links

- http://eulersdisk.com

- McDonald, Alexander J.; McDonald, Kirk T. (2000). "The Rolling Motion of a Disk on a Horizontal Plane". arXiv:physics/0008227

.

. - "Euler's Disk". Real World Physics Problems. real-world-physics-problems.com. Retrieved 2014-07-11. Detailed mathematical physics analysis of disk motion