Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

| Ernest II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ernest II, c. 1880. | |||||

| Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | |||||

| Reign |

29 January 1844 – 22 August 1893 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ernest I | ||||

| Successor | Alfred | ||||

| Born |

21 June 1818 Ehrenburg Palace, Coburg, Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, German Confederation | ||||

| Died |

22 August 1893 (aged 75) Reinhardsbrunn Castle, Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, German Empire | ||||

| Burial | Friedhof am Glockenberg, Coburg | ||||

| Spouse | Princess Alexandrine of Baden | ||||

| |||||

| House | Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | ||||

| Father | Ernest I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | ||||

| Mother | Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg | ||||

| Religion | Lutheranism | ||||

Ernest II (German: Ernst August Karl Johann Leopold Alexander Eduard; 21 June 1818 – 22 August 1893) was the sovereign duke of the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, reigning from 1844 to his death. Ernest was born in Coburg as the eldest child of Ernest III, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, and his duchess, Princess Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg. Fourteen months later, his younger brother Prince Albert was born, who later became consort of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. Ernest's father became Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in 1826 through an exchange of territories.

In 1842, Ernest married Princess Alexandrine of Baden in what was to be a childless marriage. Soon after, he succeeded as duke upon the death of his father on 29 January 1844. As reigning Duke Ernest II, he supported the German Confederation in the Schleswig-Holstein Wars against Denmark, sending thousands of troops and becoming the commander of a German corps; as such, he was instrumental in the 1849 victory at the battle of Eckernförde against Danish forces. After King Otto of Greece was deposed in 1862, the British government put Ernest's name forward as a possible successor. Negotiations fell through however for various reasons, not in the least of which was that he would not give up his beloved duchies in favor of the Greek throne.

A supporter of a unified Germany, Ernest watched the various political movements with great interest. While he initially was a great and outspoken proponent of the liberal movement, he surprised many by switching sides and supporting the more conservative (and eventually victorious) Prussians during the Austro-Prussian and Franco-Prussian wars and subsequent unification of Germany. His support of the conservatives came at a price however, and he was no longer viewed as the possible leader of a political movement. According to historian Charlotte Zeepvat, Ernest became "increasingly lost in a whirl of private amusements which earned only contempt from outside".

Ernest's position was often linked to his brother Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria. The two boys were raised as though twins, and became closer upon the separation and divorce of their parents, as well as the eventual death of their mother. The princes' relationship experienced phases of closeness as well as minor arguments as they grew older; after Albert's death in 1861, Ernest became gradually more antagonistic to Victoria and her children, as well as increasingly bitter toward the United Kingdom, publishing anonymous pamphlets against various members of the British royal family. Despite their increasingly differing political views and opinions however, Ernest accepted his second eldest nephew Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh as his heir-presumptive, who upon Ernest's death on 22 August 1893 at Reinhardsbrunn, succeeded to the ducal throne.

Early life

Ernest, Hereditary Prince of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, was born at Ehrenburg Palace in Coburg on 21 June 1818.[1] He was the elder son of Ernest III, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld and his first wife Princess Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg. He was soon joined by a brother, Prince Albert, who would later become the husband of Queen Victoria. Though Duke Ernest fathered numerous children in various affairs, the two boys would have no other legitimate siblings. In 1826, their father succeeded as Ernest I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha through an exchange of territories after the death of the duke's uncle, Frederick IV, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg.[2]

There are various accounts of Ernest's childhood. When he was fourteen months old, a servant commented that Ernest "runs around like a weasel. He is teething and as cross as a little badger from impatience and liveliness. He is not pretty now, except his beautiful black eyes".[3] In May 1820, his mother described Ernest as "very big for his age, as well as intelligent. His big black eyes are full of spirit and vivacity".[4] Biographer Richard Hough writes that "even from their infancy, it was plainly evident that the elder son took after his father, in character and appearance, while Albert strongly resembled his mother in most respects".[5] Ernest and his brother often lived with their grandmother the Dowager Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld until her death in 1831.

He and Albert were brought up and educated together as if they were twins.[6] Though Albert was fourteen months younger, he surpassed Ernest intellectually.[6] According to their tutor, "they went hand-in-hand in all things, whether at work or at play. Engaging in the same pursuits, sharing the same joys and the same sorrows, they were bound to each other by no common feelings of mutual love".[7] Perhaps the "sorrows" aforementioned related to their parents' marriage. It was not a happy one and Duke Ernest I was continually unfaithful.[8] In 1824, Ernest I and Louise divorced; she subsequently left Coburg and was disallowed from seeing her sons again.[9] She soon remarried to Alexander von Hanstein, Count of Pölzig and Beiersdorf, dying in 1831 at the age of thirty.[10] The year after her death, their father married his niece Duchess Marie of Württemberg, who was his sister Antoinette's daughter. Their stepmother was thus also their first cousin. The duke and his new duchess were not close, and would produce no children; while the boys formed a happy relationship with their stepmother, Marie had little to no input in her stepsons' lives.[11] The separation and divorce of their parents, as well as the later death of their mother left the boys scarred and in close companionship with each other.[12]

In 1836, Ernest and Albert visited their matrimonially eligible cousin Princess Victoria of Kent, spending a few weeks at Windsor.[13] Both boys, and especially Albert were considered by his family to be a potential husband for the young princess, and they were both taught to speak competent English.[14] Their father first thought that Ernest would make a better husband to Victoria than Albert, possibly because his sporting interests would be better received by the British public.[15] Most others favored Albert over Ernest as a possible husband however. Temperamentally, Victoria was much more like Ernest, as both were lively and sociable with a love for dancing, gossip, and late nights; conversely, this fast pace made Albert physically ill.[16] Victoria believed Ernest had a "most kind, honest, and intelligent expression in his countenance", while Albert "seemed full of goodness and sweetness, and very clever and intelligent".[14] No offer of marriage was forthcoming for either brother however, and they returned home.

Ernest entered military training later that year.[16] In April 1837, Ernest and Albert and their household moved to the University of Bonn.[17] Six weeks into their academic term, Victoria succeeded as Queen of the United Kingdom. As rumors of an impending marriage between her and Albert interfered with their studies, the two brothers left on 28 August 1837 at the close of the term to travel around Europe.[18] They returned to Bonn in early November to continue their studies. In 1839, the brothers traveled to England again, where Victoria found her cousin Albert agreeable and soon proposed.[19] This connection would have many implications upon Ernest in the future; for instance, he was selected as godfather for Albert's second daughter Princess Alice, and would eventually come to give her away at her wedding, only months after Albert's death.[20]

Marriage

Various candidates were put forward as a possible wife for Ernest. His own father wanted him to look high-up for a wife, such as a Russian grand duchess.[22] One possibility was Princess Clémentine of Orléans, a daughter of Louis Philippe I, whom he met while visiting the court at the Tuileries.[23] Such a marriage would have required his conversion from Lutheranism to Roman Catholicism however, and consequently nothing came of it.[23] She later married his cousin Prince August of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Ernest was also considered by Dowager Queen Maria Christina as a possible husband for her young daughter Isabella II of Spain,[24] and by Queen Victoria for her cousin Princess Augusta of Cambridge.[25]

In Karlsruhe on 3 May 1842, Ernest married 21-year-old Princess Alexandrine of Baden.[26] She was the eldest daughter of Leopold, Grand Duke of Baden and Princess Sophie of Sweden, daughter of the deposed King Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden. Though he gave his consent, his father was disappointed that his second son did not do more to advance the concerns of Coburg.[22] The marriage did not produce any issue, though Ernest apparently fathered at least three illegitimate children in later years.[25]

Ernest had suffered from a venereal disease in his late teens and early twenties, most likely as the consequence of living a wild, promiscuous lifestyle.[16] These qualities he had inherited under the tutelage of his father, who took his sons to "sample the pleasures" of Paris and Berlin, to Albert's "horror and shame".[23] Ernest had been so visibly deteriorating in appearance as a result that Sarah Lyttelton, a lady-in-waiting of Queen Victoria, observed at Windsor in 1839 that he was "very thin and hollow-cheeked and pale, and no likeness to his brother, nor much beauty. But he has fine dark eyes and black hair, and light figure, and a great look of spirit and eagerness".[16] Later that year, Albert counseled his brother against finding a wife until his 'condition' was fully recovered.[22] He further warned that continued promiscuity could leave Ernest incapable of fathering children.[16] Some historians believe that while he himself was able to father other children, the disease rendered his young wife infertile.[25]

As the years went by with further childlessness, Ernest became more distant to his wife, and was continually unfaithful. Though Alexandrine continued to be devoted, choosing to ignore those relationships she was aware of, her loyalty became increasingly baffling to those outside her immediate family.[27] By 1859, after seventeen years of childlessness, Ernest took no further interest in his wife.[28]

Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

On 29 January 1844, Ernest's father died in Gotha, one of the territories their family had recently acquired. Ernest consequently succeeded to the duchies of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha as Ernest II.[29]

Development of a constitution

Extravagant to a great degree, Ernest had many money troubles throughout his reign. In January 1848, Ernest visited his brother in the midst of political unrest in Germany. Upon his return, he also discovered unrest in Coburg. One of the many concerns related to finances. Although Ernest had a large inheritance, he also had frequent debts.[21] There were increasing calls to nationalize most of his property. Indeed, Albert had to intervene at one point and spare his brother the embarrassment of losing one of his Coburg properties.[21]

During the 1848 turmoil in Germany, Albert had been constructing his own liberal reform plan, under which a single monarch, chancellor, and parliament would unite the German states; in addition, each state would retain its own current ruling dynasty.[21] As this plan pertained to his brother, Ernest was given a copy in the hope that he would develop his own liberal constitution. Ernest subsequently made a few concessions, but his position remained sound, not counting the increasing problem of his debts.[21] A constitution was drafted and promulgated in 1849 in Gotha,[29] though one had existed in Coburg since 1821. In 1852, both constitutions were converged into one, which converted the personal union of the two duchies into a real union; the duchies were now inseparable, with a common set of institutions.[2] During the political turmoil, timely concessions and Ernest's popular habit of mingling with "the people in their pleasures" were instrumental in keeping him from losing his throne.[30] Furthermore, various contemporary sources state that Ernest was an able, just and very popular ruler, which may have also helped keep him in power.[31]

Schleswig-Holstein wars

From 1848 to 1864, Denmark and the German Confederation fought over control of the two duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. Historically, the duchies had been ruled by Denmark since medieval times, but there remained a large German majority. This majority was sparked to rebellion after Frederick VII of Denmark announced on 27 March 1848 the duchies would become an integral part of Denmark under his new liberal constitution. Prussia soon became involved, supporting the uprising and beginning the First Schleswig War. Ernest sent 8,000 men initially, adding to the army sent by the German Confederation. He also desired to be given a military job during the war, but was refused, as it was "extremely difficult to offer me a position in the army of Schleswig-Holstein corresponding to my rank", according to his memoirs.[32] He agreed to a smaller command, coming to lead a Thuringian contingent; he commented in a letter to his brother that "I should have declined any other command of the kind, but I could not refuse this one, as, in the present condition of our States, it is important to keep the executive power in our hands".[33] As commander of a German corps, Ernest was instrumental in winning the 5 April 1849 battle of Eckernförde against Danish forces.[34]

The first war ended in 1851, but would resume in 1864. During this interlude, Ernest fervently opposed the marriage of his nephew Albert Edward, Prince of Wales ('Bertie') to Princess Alexandra of Denmark, a daughter of the future Christian IX of Denmark (and therefore an enemy of the German states). He believed that such a match flew in the face of German interests.[35] Albert replied angrily "What has that got to do with you?... Vicky has racked her brains to help us to find someone, but in vain...We have no [other reasonable] choice".[36] Albert agreed there were going to be problems with the match, but as he could find no alternative bride, he wrote to Ernest that keeping the affair a private matter (and outside the realm of government) was "the only way to prevent a break with Prussia and the only way to keep the game in our own hands, impose the conditions that we think necessary, and as far as we can, take off its political edge".[37] Albert also warned his son of Ernest's endeavors to interfere with the match, commenting, "Your uncle...will try his hand at this work. Your best defence will be not to enter on the subject, should he broach it".[38]

Soon after writing these letters, Prince Albert died on 14 December 1861. His death helped Ernest repair his relationship with his sister-in-law, as Victoria had been becoming increasingly angrier over Ernest's objections to the Danish match. The two brothers had always been close, whatever their disagreements, and Albert's death left Ernest "wretched", noted Victoria in a letter to her eldest daughter.[28] The death did not solve their argument however; seeing that his direct involvement had failed to persuade Victoria, Ernest tried a new tactic. He began to spread gossip about Alexandra and her family, in which her mother Princess Louise "had had illegitimate children and Alexandra had had flirtations with young officers"; he also wrote to Louise herself, warning that Bertie would be an unfortunate choice for a husband.[39] Additionally, Ernest met with his nephew at Thebes, most likely attempting to discourage him from the match in person.[40] In an 11 April letter, Victoria unhappily noted to her eldest daughter "You did not tell me that Bertie had met Uncle Ernest at Thebes...I am always alarmed when I think of Uncle Ernest and Bertie being together as I know the former will do all he can to set Bertie against the marriage with Princess Alix".[37] Despite Ernest's disapproval, Bertie was duly married to Alexandra on 10 March 1863.

The Duke had a reputation for being a strong friend of the United States, as did his brother Albert. He was, however, the only European sovereign to appoint a consul, Ernst Raven, to the Confederate States of America, on 30 July 1861. The Texas government, where Raven resided, made it clear, however, that his request for an exequatur did not imply or extend diplomatic recognition to the Confederate regime.[41]

Nomination for the Greek throne

On 23 October 1862, Otto of Bavaria, King of Greece was deposed in a bloodless coup. The Greeks were eager to have someone close to Britain and Queen Victoria replace Otto; some desired to allow Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh (her second son) succeed as King of Greece.[42] He was elected with 95% of the vote in the Greek head of state referendum of 1862. After his ineligibility was confirmed however, the Greeks began looking for other possible candidates, which included Duke Ernest at the British government's suggestion.[43] To their and Victoria's reasoning, if Ernest were to take the Greek throne, Alfred could immediately take up his inheritance and succeed Ernest as duke (the Prince of Wales having passed his claim to the duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha onto his younger brother).[43] Many were in favor of his nomination, including Prime Minister Lord Palmerston and Ernest's sister-in-law. In a letter written to her uncle Leopold I of Belgium, Victoria stated her support for a new royal branch of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (as Leopold had been chosen as King of the Belgians in 1831) as well as her desire for her second son Alfred to succeed his uncle in the duchy.[44] As negotiations continued however, she began to lose enthusiasm for the idea.[43]

There were problems to the nomination; Ernest had no children, and thus would have had to adopt one of the princes of his house to succeed him as King of Greece. To solve this problem, Ernest suggested to Palmerston that he simply take the title regent of Greece and hold the kingdom in trust for his chosen heir.[44] He also stipulated that if he accepted the throne, it should be subject to certain guarantees by the other powers. The apparent deal-breaker however was the fact that Ernest wanted to acquire the Greek throne and still maintain control of his "safer" duchies.[43] In the end, the British cabinet thought the proposed conditions unacceptable. His proposals turned down, Ernest in turn refused. In 1863, the Greek throne was accepted by another member of a royal family: the Princess of Wales' younger brother Prince William of Denmark. Ernest would later comment, "That this cup was spared me, I always regarded as a piece of good fortune".[45]

Austro-Prussian and Franco-Prussian Wars

Ernest, like his brother, was in favor of a German unified, federal state.[46] To best realize this goal, Ernest liked to dabble in whatever political system promised the most success.[21] He subsequently watched the growth of liberalism in Germany with much interest and tried to build links with the movement's leaders. During Albert's lifetime, Ernest took a close interest in the movement for reform, and was perceived as a progressive within Germany.[47] His favorable view of liberalism caused his duchy to become an asylum for political refugees from other German states.[48] In 1863, he attended the liberal Frankfurt Conference, which was openly avoided by more conservative Prussia.[43] Though his attendance made him no friends in Prussia, he developed such strong contacts in Austria that many looked to him as a potential leader in the mounting conflict between the northern and southern powers.[43] He grew tired of the advice he received from Albert on the subject however; as Ernest "was by no means inclined to consent to an energetic rule such as I adopted immediately afterwards for the perfection of the constitutional system", according to Albert's letters.[49]

The Austro-Prussian War was triggered by the desire of German conservative leaders to unify, albeit on different terms than their liberal counterparts. Ernest urged Prussian leaders against the impending war, and was an active advocate of the Austrian cause.[43] Though Ernest normally followed more liberal politics than many of his counterparts, he began switching his views to align more closely with Prussian Minister President Otto von Bismarck by the mid-1860s. Despite this change in his private political views, he still had strong publicly known Austrian ties, and no one foresaw that Ernest would immediately side with the better-equipped Prussians upon breakout of the war.[43] His reasoning is usually understood as acting in the best interests of his duchies, and by extension, of himself.[43] Regardless, it was seen as a betrayal of former friends; Queen Victoria commented that Ernest "might have agreed to neutrality - for that might be necessary, but to change colours I cannot think right".[43]

Ernest was fortunate in his support of victorious Prussia; many other petty German dukes, princes, and kings who had supported Austria suffered immensely at Hohenzollern hands. Hanover, Hesse-Kassel, and Nassau for instance were all annexed to Prussia at the expense of their respective rulers. Though he had only recently changed his political views, Ernest was allowed to ride at the head of his battalion during the victory parade. His eldest niece Prussian Crown Princess Victoria ("Vicky") was for one pleased with his Prussian support and commented "I am not accustomed to hearing so much praise of Coburg here. [Ernest] was not among the crushed and beaten foe, it is sad enough as it is to see so many of one's friends suffering from the effects of their miscalculations".[50] Victoria's husband Crown Prince Frederick was also pleased with Ernest's decision, writing in his journal 28 September 1871, that the duke's "society always affords me peculiar pleasure, especially...when his heart beats so warmly for Germany".[51]

Ernest's support of the Prussians in the Austro-Prussian War and later Franco Prussian War meant he was no longer the potential leader of a political movement; although it was true that he had been able to retain his duchies, it had come at a price. According to historian Charlotte Zeepvat, Ernest "was increasingly lost in a whirl of private amusements which earned only contempt from outside".[52] Ernest funneled his political thoughts into the private sphere, preferring to write covertly sponsored articles in the Coburg press that became increasingly embittered against England.[53] In 1886, Ernest published Co-Regents and Foreign Influence in Germany, a pamphlet that greatly angered his family; though produced anonymously, no one doubted that it was written by Ernest. It attacked Vicky as a disloyal German that was too dependent on her mother, and declared that she had been too indiscreet in passing along confidential information during both war and peacetime.[54] Queen Victoria was furious, writing to Vicky, "What you told me of Uncle E and that pamphlet is simply monstrous. I assure you that I felt great difficulty in writing to him for his birthday, but I wrote it as short and cool as I could consistently with civility".[54] "Dear Uncle Ernest does us all a great deal of harm by his odd ways and uncontrollable tongue with his very lively imagination".[53]

Later years

Later in his reign, Ernest's actions managed to continually anger his sister-in-law. Though Victoria loved Ernest because he was Albert's brother, she was displeased that Ernest was writing his memoirs, worrying about their contents mainly in regard to her dead husband.[55] Despite their disputes, Ernest still met with Victoria and her family occasionally. In 1891, they met in France; Victoria's lady-in-waiting commented "the old Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha has been here today with his wife. He is the Prince Consort's only brother and an awful looking man, the Queen dislikes him particularly. He is always writing anonymous pamphlets against the Queen and the Empress Frederick, which naturally creates a great deal of annoyance in the family".[56]

Throughout his reign, Ernest had been known for his extravagance and womanizing; as he grew older, Ernest enjoyed gossip and was "now a thoroughly disreputable old roué who enjoyed the outrage provoked by his actions", leading Vicky to declare that her uncle "was his own enemy".[53] His behavior and manner of dress increasingly became a joke for younger generations.[55] His great-niece Marie of Edinburgh would later describe Ernest as "an old beau, squeezed into a frock-coat too tight for his bulk and uncomfortably pinched in at the waist', sporting a top hat, lemon coloured gloves, and a rosebud in his lapel".[55] He put on weight and though on paper his wealth was large, he was still constantly in debt.[53]

An excellent musician[30] and amateur composer all his life, Ernest was a great patron of the arts and sciences in Coburg,[57] often giving awards and titles to members of the artistic and scientific world, such as Paul Kalisch, a German opera singer and chemist William Ernest Bush. Ernest composed songs, hymns, and cantatas, as well as musical pieces for opera and the stage, including Die Gräberinsel (1842), Tony, oder die Vergeltung (1849), Casilda (1851), Santa Chiara (1854), and Zaïre, which met with success in Germany.[30] He could also draw and play the piano.[58] One of his operas, Diana von Solange (1858), prompted Franz Liszt the following year to write an orchestral Festmarsch nach Motiven von E. H. z. S.-C.-G., S.116 (E. H. z. S.-C.-G. was short for Ernst Herzog zu Sachsen-Coburg-Gotha).[59] However, its production at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City in 1890 inspired dismal reviews, with one spectator commenting that its "music was simply rubbish".[60] Ernest was also an avid hunter and sportsman; one contemporary remarked that he was "one of the foremost and keenest sportsman produced by the present century".[61] In addition, Ernest was an enthusiastic patron of everything connected with natural history,[61] for instance traveling to Abyssinia with the German zoologist Alfred Brehm in 1862.

Ernest II died at Reinhardsbrunn on 22 August 1893 after a short illness.[62] A lifelong sportsman, his last words were apparently "Let the drive commence!"[61] His funeral was held in the Morizkirche in Coburg; thousands of spectators came to the funeral, including Emperor Wilhelm and the Prince of Wales.[63] He is buried in the ducal mausoleum in the Friedhof am Glockenberg which he himself had built in 1853-8.[64]:47

Ernest was succeeded by his nephew Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh.

Inheritance to Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

For much of Ernest's reign, the heir presumptive to Saxe-Coburg and Gotha was his only sibling Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria.[2] When it became increasingly more clear that Ernest would be childless, the possibility of a personal union between his duchies and the United Kingdom became real, a reality that was deemed undesirable.[2] Special arrangements were made by a combination of constitutional clauses and renunciations to pass Ernest's throne to a son of Albert while preventing a personal union.[2] Consequently, Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, his brother's second eldest son, was designated the childless Ernest's heir presumptive on 14 December 1861, when his older brother the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII of the United Kingdom) renounced his succession rights.

Issues arose over authority to control the upbringing of his heir-presumptive. As head of the Coburg family, Ernest would normally have been able to arrange Alfred's education and general upbringing unchallenged.[21] This however was not the case. Alfred was torn between his British birth and his German inheritance. This was partly because Alfred was second-in-line to the United Kingdom until the birth of his nephew Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, in 1864. One example of the many problems of his education concerned the language he would speak. Although he grew up learning German, his native language was decided to be English. In addition, a naval career was chosen for Alfred, a common profession for a British prince but almost unheard of for a prince of Germany.[21] Ernest also wanted Alfred to be educated in Coburg, but his brother refused. Albert's refusal most likely stemmed from the negative British reaction that would have inevitably occurred and the fact that Albert was fearful of Alfred's moral development.[21] Thus despite Ernest's protests, he went unheeded in Albert's lifetime. In 1863, Ernest told Victoria that it was time for Alfred to leave the navy and enter a German university. By March of the following year, it was decided that Alfred would attend Bonn University but be left to consider his future, as he was having reservations over permanently residing outside England.[43] The matter was eventually resolved; Alfred came to accept his inheritance, and Victoria understood and accepted that Ernest needed to be involved in the upbringing of his heir-presumptive, with a strong German element added to his education and (carefully chaperoned) visits to Coburg.[43]

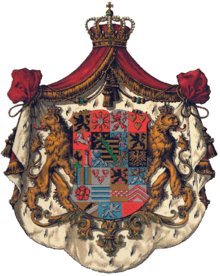

Titles, styles, honours, and arms

Titles and styles

- 21 June 1818 – 12 November 1826: His Serene Highness The Hereditary Prince of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld

- 12 November 1826 – 29 January 1844: His Highness The Hereditary Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

- 29 January 1844 – 22 August 1893: His Highness The Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Honours

- KJ: Knight of St. Joachim

- Grand Master of the Order of the Ernestine House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha

- Master Mason, 1857[65]

Foreign

- KG: Knight of the Garter, 1844[21]

- Recipient of the Iron Cross of 1870, 1st and 2nd class[66]

Ancestry

See also

References

- ↑ Grey, p. 29 and Weintraub, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 François Velde. "House Laws of the Saxe-Coburg and Gotha". Heraldica.org. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ Grey, pp. 32-33.

- ↑ Grey, p. 35.

- ↑ Hough, p. 9.

- 1 2 Weintraub, p. 30.

- ↑ Grey, p. 44.

- ↑ Weintraub, pp. 23-25.

- ↑ Weintraub, p. 25-28.

- ↑ Feuchtwanger, pp. 29-31.

- ↑ Packard, p. 16 and Weintraub, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Weintraub, pp. 25–28.

- ↑ Feuchtwanger, p. 37.

- 1 2 Weintraub, p. 49.

- ↑ D'Auvergne, p. 164.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Zeepvat, p. 1.

- ↑ Feuchtwanger, pp. 35-36.

- ↑ Weintraub, p. 58-59.

- ↑ Feuchtwanger, pp. 38-39.

- ↑ Packard, p. 104.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Zeepvat, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 Feuchtwanger, p. 62; Gill, pp. 142-43.

- 1 2 3 Weintraub, p. 52.

- ↑ D'Auvergne, pp. 188-89.

- 1 2 3 Gill, p. 143.

- ↑ Zeepvat, p. 2 and Lundy.

- ↑ Zeepvat, pp. 2, 5.

- 1 2 Zeepvat, p. 3.

- 1 2 Encyclopædia Britannica. "Ernest II". Britannica.com. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 Coit Gilman et al, p. 841.

- ↑ Baillie-Grohman, p. 60 and Kenning, pp. 204-05.

- ↑ Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Volume 1, p. 48. A letter written to him by his servant Von Stein states that while there were many candidates who could take command of parts of the army, there was only one Duke, hinting that Ernest was needed to continue promulgating the German Constitution in his duchy.

- ↑ Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Volume 1, p. 50.

- ↑ Coit Gilman et al, p. 841 and Alden, Berry, Bogart et al, p. 481.

- ↑ Zeepvat, p. 3 and Hibbert, p. 43.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 42.

- 1 2 quoted in Zeepvat, p. 3.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 43.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 57.

- ↑ Zeepvat, p. 3 and Hibbert, p. 57.

- ↑ Berwanger, p. 111.

- ↑ D'Auvergne, pp. 269-270 and Zeepvat, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Zeepvat, p. 4.

- 1 2 D'Auvergne, p. 271.

- ↑ D'Auvergne, p. 272.

- ↑ Zeepvat, p. 2 and Coit Gilman et al, p. 841.

- ↑ Zeepvat, p. 4 and Alden, Berry, Bogart et al, p. 481.

- ↑ Alden, Berry, Bogart et al, p. 481.

- ↑ quoted in Zeepvat, p. 2.

- ↑ Pakula, p. 241 and Zeepvat, p. 5.

- ↑ Allinson, p. 139.

- ↑ Zeepvat, p. 5. Victoria wrote in 1873, "The accounts of Uncle Ernest's conduct are too distressing", and two weeks later to her Vicky, "What you say about Uncle E. alas! alas! is what I have heard from but too many and is most painful and humiliating. Really one cannot go to Coburg when Uncle is there".

- 1 2 3 4 Zeepvat, p. 5.

- 1 2 Zeepvat, p. 6 and Feuchtwanger, p. 209.

- 1 2 3 Zeepvat, p. 6.

- ↑ quoted in Zeepvat, p. 6.

- ↑ "Obituary". The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. 34 (607): 539–540. 1893. JSTOR 3363520.

- ↑ Weintraub, p. 50 and The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, pp. 539-540.

- ↑ Grove's Dictionary of Music, 5th ed, 1954, Liszt: Works, p. 275

- ↑ "Amusements", The New York Times, The Metropolitan Opera House, 10 January 1891

- 1 2 3 Baillie-Grohman, p. 60.

- ↑ Zeepvat, p. 6 and Baillie-Grohman, p. 60.

- ↑ "Buried in the Moritzkirche", The New York Times, Coburg, 29 August 1893

- ↑ Klüglein, Norbert (1991). Coburg Stadt und Land (German). Verkehrsverein Coburg.

- ↑ Kenning, pp. 204-05.

- ↑ Allinson, p. 112.

Sources

Primary

- Baillie-Grohman, William Adolph (1896). Sport in the Alps in the Past and Present: An Account of the Chase of the Chamois, Red-deer, Bouquetin, Roe-deer, Capercaillie, and Black-cock, with Personal References and Historical Notes and Some Sporting Reminisces of H.R.H. the Late Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. London: Scribner.

- Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Duke Ernest II of (1888). Memoirs of Ernest II: Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. London: Remington & Co. Publishers., four volumes.

Secondary

- Alden, Raymond; George Berry; Ernest I. Bogart; et al. (1918). The Encyclopedia Americana: A Library of Universal Knowledge, Volume 10. New York: The Encyclopedia Americana Corporation.

- Allinson, A.R. (2006). The War Diary of the Emperor Frederick III - 1870 - 1871. Home Farm Books. ISBN 1-4067-9995-5.

- Berwanger, Eugene H. (1994). The British Foreign Service and the American Civil War. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1876-X.

- Coit Gilman, Daniel; Harry Thurston Peck; Frank Moore Colby (1903). The New International Encyclopædia, Volume 6. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company.

- D'Auvergne, Edmund Basil (1911). The Coburgs: The Story of the Rise of a Great Royal House. New York: James Pott & Company. ISBN 1-120-85860-7.

- Feuchtwanger, E.J. (2006). Albert and Victoria: The Rise and Fall of the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. London: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 1-85285-461-8.

- Gill, Gillian (2009). We Two: Victoria and Albert: Rulers, Partners, Rivals. New York: Ballatine Books. ISBN 0-345-52001-7.

- Grey, Hon. Charles (1868). The Early Years of His Royal Highness The Prince Consort. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers.

- Hibbert, Christopher (2007). Edward VII: The Last Victorian King. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hough, Richard (1996). Victoria and Albert. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-30385-8.

- Kenning, George (1878). Kenning's Masonic Encyclopedia and Handbook of Masonic Archeology, History and Biography. London: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-6526-4.

- Packard, Jerome M. (1998). Victoria's Daughters. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-24496-7.

- Pakula, Hannah (1997). An Uncommon Woman: The Empress Frederick, Daughter of Queen Victoria, Wife of the Crown Prince of Prussia, Mother of Kaiser Wilhelm. New York: Simon and Schuster Inc. ISBN 0-684-84216-5.

- Weintraub, Stanley (1997). Uncrowned King: The Life of Prince Albert. London: John Murray Inc. ISBN 0-7195-5756-9.

- Zeepvat, Charlotte (July 2000). "The Queen and Uncle E". Royalty Digest. X (109): 1–7. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. |

- Biography of Ernest II at the German National Library. (German)

- Biography of Ernest II at the Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie. (German)

| Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha Cadet branch of the House of Wettin Born: 21 June 1818 Died: 22 August 1893 | ||

| German royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ernst I |

Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha 29 January 1844 – 22 August 1893 |

Succeeded by Alfred |