Ephrata Cloister

|

Ephrata Cloister | |

|

Photograph of Ephrata Cloister buildings in December 2006 | |

| Location | Jct. of US 322 and 272, Ephrata, Pennsylvania, USA |

|---|---|

| Area | 30 acres (12 ha) |

| Built | 1732 |

| NRHP Reference # | 67000026[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | December 24, 1967[1] |

| Designated NHL | December 24, 1967[2] |

| Designated PHMC | March 18, 1947[3] |

| Part of a series on the |

| Schwarzenau Brethren (the German Baptists or Dunkers) |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Christianity · Protestantism · Anabaptism · Radical Pietism · Radical Reformation |

| Doctrinal tenets |

| Non-creedalism · Trine baptism · Love feast · Feet washing · Holy kiss · Free church · Anointing with oil · Non-resistance · Pacifism · The Brethren Card |

| People |

| Alexander Mack · Louis Bauman · Conrad Beissel · Donald F. Durnbaugh · Vernard Eller · Christoph Sauer · John C. Whitcomb |

| Groups |

|

Brethren Church · Church of the Brethren · Conservative Grace Brethren · Dunkard Brethren · Grace Brethren · Old Brethren · Old Brethren German Baptist · Old German Baptist Brethren · Old German Baptist Brethren, New Conference · Old Order German Baptist Brethren · |

| Related movements |

| Amish · Bruderhof · Community of True Inspiration · Hutterites · Mennonites · River Brethren · Quakers |

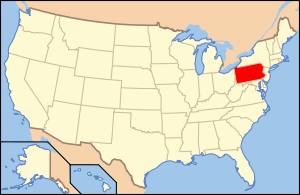

The Ephrata Cloister or Ephrata Community was a religious community, established in 1732 by Johann Conrad Beissel at Ephrata, in what is now Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. The grounds of the community are now owned by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and are administered by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

Marie Kachel Bucher, the last surviving resident of the Ephrata Cloister, died on July 27, 2008, at the age of 98.[4]

History

The community was descended from the pietistic Schwarzenau Brethren movement of Alexander Mack of Schwarzenau in Germany. The first schism from the general body occurred in 1728—the Seventh Day Dunkers, whose distinctive principle was that the seventh day was the true Sabbath.

In 1732, Beissel arrived at the banks of Cocalico Creek in Lancaster County. Around this charismatic leader a semi-monastic community (the Camp of the Solitary) with a convent (the Sister House) and a monastery (the Brother House) was established, called "Ephrata". The members of the order were celibate. In addition to celibacy, the members believed in strict interpretation of the Bible, and self-discipline. Members were required to sleep on wooden benches 15 inches (380 mm) wide, with wooden blocks for pillows. They slept six hours per night, from 9 P.M. to midnight, and from 2 A.M. until 5 A.M., with a two-hour break to "watch" for the coming of Christ. They ate one small vegetarian meal a day. The only time the followers of Beissel were permitted to eat meat was during the celebration of communion when lamb was served. The members of the cloister spent much time at work or praying privately. Services every Saturday were led by Beissel, often being several hours long.

During the time that this group formed, there was a hint of dissatisfied intellectualism of churches. Many wanted to be away from state established churches. Strict religious lives caused these brothers and sisters to come together to worship God in other ways. Instead of practicing their religion, they applied it by helping others to become more spiritual and celibate.

Among the sisterhood and brotherhood there included a married order of householders, which were families who supported and engaged in the everyday activities. Other than practicing quiet lives by praying and doing charity work,[5] the Cloisters had a duty to keep up with the tasks of living at Ephrata. Farming and industrial work were the typical workload on a daily basis. Although the Cloisters often practiced their religion by interpreting Biblical works, they also engaged in carpentry and papermaking. Other tasks included gardening, preparing meals, and mending.[6] Not only were the cloisters famous for their writings and hymns on the printing press but they became very busy people especially when it came to chores. They manufactured clothing on a mill and kept their lives busy by creating duties and obligations.

The Cloisters had a positive outlook in life; they respected their neighbors, land and environment. Education was also important in their society. It was important that every child maintain their education. Children that came from families were also encouraged to be educated in the German school. Educating the young was one of the charity works that the Cloisters accomplished. They also helped the poor by passing around bread to the poor families.

Other believing families settled near the community, accepted Beissel as their spiritual leader and worshipped with them on Sabbath. These families made an integral part to the cloister, which could not be self-sustaining without them. The brothers and sisters of Ephrata are famous for their writing and publishing of hymns, and the composition of tunes in four voices. Beissel served as the community's composer as well as spiritual leader, and devised his own system of composition. The Ephrata hymnal (words only) was printed in 1747.

The Ephrata Cloister had the second German printing press in the American colonies and also published the largest book in Colonial America. The book, Martyrs Mirror, is a history of the deaths of Christian martyrs from the time of Christ until 1660. Before the publication began at the request of a group of Mennonites from Montgomery County, it had to be translated from the original Holland Dutch into German, which was completed by Peter Miller of the Ephrata Community. Work began in 1748 and was finished about three years later. Many of the books were purchased by the Montgomery County Mennonites who had initiated the process.

The charismatic Beissel died in 1768, and this contributed to a declining membership. The monastic aspect was gradually abandoned, with the last celibate member dying in 1813. In 1814 the Society was incorporated as the German Seventh Day Baptist Church (or The German Religious Society of Seventh Day Baptists). Branches were established in other locations, some still surviving in 2009. In 1941, a 28 acres (110,000 m2) Ephrata tract of land with remaining buildings was conveyed to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for use as a state historical site. The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission led excavations there which, among other things, uncovered of the Cloister's use as a Revolutionary War hospital. Of special note, the only glass trumpet of its kind in North America was unearthed by archaeologists in 1998 at the Cloister. The trumpet, which likely came from Germany, was found in excellent condition which led archaeologists to believe it was intentionally buried. The mouthpiece was the only part missing from the trumpet, so it is unknown if it has ever been played.

At its height, the Ephrata community grew to 250 acres (1.0 km2) inhabited by about 80 celibate men and women. The married congregation numbered approximately 200.

Gallery

Buildings at Ephrata cloister

Buildings at Ephrata cloister Tombs with inscription in German

Tombs with inscription in German Living quarters

Living quarters Praying room

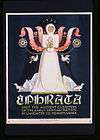

Praying room WPA poster, 1936-1941

WPA poster, 1936-1941

See also

References

- 1 2 National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Ephrata Cloister". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ↑ "PHMC Historical Markers". Historical Marker Database. Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Obituary of Marie Elizabeth Kachel Bucher". Intelligencer Journal. 2008-07-29. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ History, Ethnic – Ephrata Cloister

- ↑ Ephrata Cloister

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ephrata cloister. |

- Official website

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. PA-320, "The Cloisters"

- Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission – Ephrata Cloister

- Ephrata Cloister – information on the community at Church of the Brethren Network

- German Seventh-Day Baptists – congregations tracing their origins to Ephrata