Empty category

In linguistics, in the study of syntax, an empty category is a nominal element that does not have any phonological content and is therefore unpronounced.[1] Empty categories may also be referred to as covert nouns, in contrast to overt nouns which are pronounced.[1] The phenomenon was named by Noam Chomsky in his 1981 LGB framework.[1] Some empty categories are governed by the empty category principle. When representing empty categories in trees, linguists use a null symbol to depict the idea that there is a mental category at the level being represented, even if the word(s) are being left out of overt speech. There are four main types of empty categories: NP-trace, Wh-trace, PRO, and pro. The types are differentiated by their two binding features: the anaphoric feature [a] and the pronominal feature [p]. The four possible combinations of plus or minus values for these features yield the four types of empty categories.[2] Empty categories are present in most of the world's languages, although different languages allow for different categories to be empty.

| [a] | [p] | Symbol | Name of empty category | Corresponding overt noun type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | t | Wh-trace | R-expression |

| - | + | pro | "little Pro" | pronoun |

| + | - | t | NP-trace | anaphor |

| + | + | PRO | "big Pro" | none |

In the table, [+a] refers to the anaphoric feature, meaning that the particular element must be bound within its governing category. [+p] refers to the pronominal feature which shows that the empty category is taking the place of an overt pronoun.

Generation

Not all empty categories enter the derivation of a sentence at the same point. Both NP-trace and Wh-trace are only generated as the result of movement operations. Trace refers to the syntactic position which is left after something has moved, helping to explain how NP-trace and Wh-trace get their names.[1] What is meant by "trace" is that there is a position in the sentence that holds syntactic content in the deep structure, but that is not present at the surface, or S-structure. Conversely, both PRO and pro are not the result of movement and must be base-generated [1] In both the government and binding and minimalism frameworks, the only method of base-generation is lexical insertion. This means that both "PRO" and pro are held to be entries in the mental lexicon, whereas Wh-trace and NP-trace are not categories in the lexicon.

Four original types according to classical theory

PRO (Big Pro)

The empty category subclass called PRO, referred to as "big pro" when speaking, is a DP which appears in a caseless position.[3] Since PRO is a caseless DP, it can appear in caseless positions, such as the specifier of a non-finite tense phrase. It helps to account for non-finite embedded clauses,[4] such as the examples below:

This example does not use PRO, but uses an overt pronoun instead ("you"):

1a) Hei would like youj to stay.

This example does use PRO, because there is an empty category which is co-referenced with "He" which appears in the specifier position of the non-finite embedded clause:

1b) Hei would like PROi to stay.

PRO takes the subject position of the non-finite clause. Meaning can be determined by its controller (the subject of the matrix clause) although it does not have to be. PRO can either be controlled ("obligatory control") or uncontrolled ("optional control").[5] The realization that PRO does not behave exactly like an R-Expression, an anaphor, or a pronoun led to the conclusion that it must be a category in and of itself. It can sometimes be bound, is sometimes co-referenced in the sentence, and does not fit into binding theory.[6]

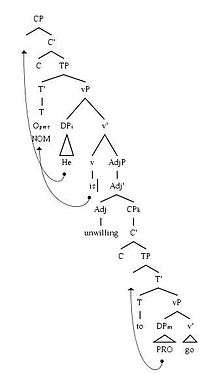

The example tree to the right is the tree for the sentence 'Hei is unwilling PROi to go.' PRO starts out as the daughter of the Verb Phrase of an embedded clause, but moves to the specifier position of the embedded clause so that the specifier position has a caseless DP; namely, PRO.

pro (little pro)

"Little pro" occurs in a subject position of a finite clause and has case.[7] The DP is ‘dropped’ from a sentence if its reference can be recovered from the context. Spanish is an example of a language with rich subject-verb morphology that can allow null subjects. The person-marking on the verb in Spanish allows the subject to be identified even if the subject is absent from the spoken form of the sentence. This does not happen in English because of its impoverished subject-verb morphology.[8] Chinese is an example of a Pro-drop language. Both subjects and objects can be dropped from the pronounced part of finite sentences, which means that what is clear from the context does not have to be uttered, leading it to be labelled as a discourse-oriented language. In pro-drop languages, the covert "pro" replaces an overt pronoun, so one ends up with sentences that do not have a subject or object pronounced on their own. They are understood based on other things (such as verbal morphology or discourse) instead. The distribution of pro-drop can be predicted: a pronoun may drop from a given sentence only if certain important aspects of its reference can be recovered from other parts of the sentence.

This example illustrates how a Chinese question would be asked with Zhangsan as the subject and Lisi as the object.[9]

2a) Zhangsan kanjian Lisi le ma?

Zhangsan see Lisi ASP Q?

‘Did Zhangsan see Lisi?’

The next example is the response to the question. Both subject and object are null categories. The meaning of the sentence can be easily recovered even though the pronouns are dropped. (Round brackets indicate an optional element.)[9]

2b)(ta) kanjian (ta) le. (He) saw (him).

2c)ta kanjian ta le. He see he Perf.

The same point can be made with overt pronouns in English, as in the sentence “John said I saw him”. In this example, the chance of picking John as the antecedent for him is clearly greater than that of picking any other person.

In example 3), the null object must be referring to the discourse topic (Zhangsan) but not the matrix subject (Lisi), since condition C of the Binding Theory states that it must be free. (Square brackets indicate that an element is covert (not pronounced), as in the second English translation.)[9]

3)Zhangsan shuo Lisi hen xihuan. Zhangsan say Lisi very like. 'Zhangsan said that Lisi liked [him].'

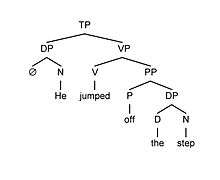

NP-trace

NP-trace is an empty category that appears when a DP moves out of its underlying position. Determiner phrases move in order to check case features. This means that if a DP cannot be matched with a verb that has the same case feature while it is still in the underlying position, it moves in order to be able to solve this problem. The place that it moves to is where one ends up pronouncing the determiner phrase.[10] NP-trace is what appears in the position that the DP was in prior to DP movement, and stands for the syntactic space in the tree that the DP previously occupied. It only occurs where case features cannot be checked (e.g. specifier VP and intransitive verbs’ complement positions).

Underlying order of words in the sentence "Cheri seems to like Tony." (Square brackets throughout example 4 indicate an empty DP category.)

4a) [ ] seems Cheri to like Tony.

Spoken form of the sentence "Cheri seems to like Tony."

4b) Cheri seems [ tDP ] to like Tony.

You can see where "Cheri" was in the initial word order by where the NP-Trace is in the spoken form.

In this example, the subject of the infinitive clause complement is moved out of the embedded clause to become the subject of matrix clause.

WH-trace

DPs can move for another reason: in the case of Wh-questions. In English, these are questions that begin with <wh> (e.g. who/whom, what, when, where, why, which, and how). The responses to these questions cannot be yes or no; they must be answered using informative phrases.[10] Wh-phrases undergo Wh-movement to the specifier of CP, leaving a Wh-trace (tWH) in its original position. It moves to check the [+WH] feature in C.

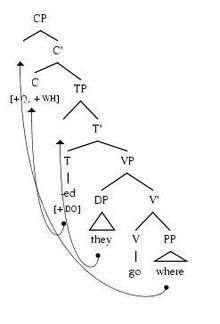

To form a Wh-question in the example to the right, the PP 'where' moves to the specifier of the CP position, leaving a Wh-trace. Due to the extended projection principle, there is DP movement to the specifier of TP position. There is also T to C movement, with the addition of Do-support. Therefore, the surface structure of the sentence yields: Where did they go tWH? [11]

The tree to the right illustrates this example of WH-trace. Initially, the sentence is "[CP] They did go where" which has an empty specifier position of CP, as indicated by square brackets. After the wh-phrase "where" moves to the beginning of the sentence, the empty position is at the end, instead of at the beginning, since the wh-phrase moves to the specifier position. What is left in its place is the Wh-trace.

An example of the Wh-phrase and complementizer relationship:

5a) [DP The person [CP who ØC [TPlikes Max]]] is here.

5b) [DP The person [CP tWH that [TPlikes Max]]] is here.

5c) * [DP The person [CP tWH ØC [TPlikes Max]]] is here.

In this example, the complementizer or the Wh-phrase can have null categories, and one or the other may show up as null. However, they cannot both be null when the wh-phrase is the subject.[12]

An important note to remember is that NP-trace and wh-trace are the result of movement operations, while the pro and PRO must be base generated.[1]

More recent work in empty functional heads: Null determiners and null complementizers

Null determiners and null complementizers are empty categories that are the result of more recent research. Not only can DPs be empty; functional categories can be empty as well. Both types are positions which end up being unpronounced at the surface level but are not included in the anaphoric and pronominal features chart that accounts for other types of empty categories.

Null determiners

Null determiners are used mainly when the Theta assignment of a verb only allows an option for a DP as a phrase category in the sentence (with no option for an NP). Proper nouns and pronouns cannot grammatically have a determiner attached to them, though they still are part of the DP phrase.[7] In this case, one needs to include a null category to stand as the D of the phrase as its head. Since a DP phrase has a determiner as its head, but one can end up with NPs that are not preceded by an overt determiner, a null symbol is used to represent the null determiner at the beginning of the DP.

Examples of nouns that do not need a determiner:

[DPØ Andrew]

[DPØ she]

The null determiners are subdivided into the same classes as overt determiners are, since the different null determiners are thought to appear in different grammatical contexts:[13]

Ø[+PROPER]

NP[+PROPER,-PRONOUN]

Ø[,+PRONOUN]

NP[+PLURAL, -PROPER, -PRONOUN]

Ø[+PLURAL]

NP[+PLURAL, -PROPER, -PRONOUN]

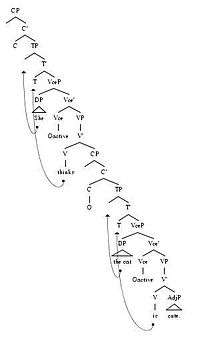

Null complementizers

Null complementizers are used in English mainly in yes-or-no questions which involve subject-auxiliary inversion.[3] The null stands in the place where the auxiliary (will, did, etc.) would have to be transferred to in order to ask a question. In linguistics, question sentences cannot be drawn in tree form: the sentence has to be rearranged so that there is the same meaning involved, but the formation is in a statement (the answer to the would-be question being asked).

Ø[-Q, +FINITE]

Ø[-Q, -FINITE]

Some other example sentences of null complementizers (round brackets indicate optionality, and the optional element has been left out in the second part of the examples, leaving it null):

6a) She thinks (that) the cat is cute.

She thinks Ø the cat is cute.

6b) This is not the tree (that) they climbed.

This is not the tree Ø they climbed.

Questions of acquisition and other possible applications

One of the main questions that arises in linguistics when examining grammatical concepts is how children learn them. For empty categories, this is a particularly interesting consideration, since, when children ask for a certain object, their guardians usually respond in “motherese”. An example of a motherese utterance which doesn't use empty categories is in response to a child’s request for a certain object. A parent might respond “You want what?” instead of “What do you want?”.[14] In this sentence, the wh-word doesn't move, and so in the sentence that the child hears, there is no wh-trace. Possible explanations for the eventual acquisition of the notion of empty categories are that the child then learns that even when he or she doesn't hear a word in the original position, they assume one is still there, because they are used to hearing a word.

At the beginning of acquisition, children do not have a concrete concept of an empty category; it is simply a weaker version of the concept. It is noted that ‘thematic government’ may be all the child possesses at a young age and this is enough to recognize the concept of empty category. The proper amount of time must be given to learn the certain aspects of an empty category (case marking, monotonicity properties, etc.).[14]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kosta, Peter, and Krivochen, Diego Gabriel. Eliminating Empty Categories: A Radically Minimalist View on Their Ontology and Justification. Frankfurt: Peter Lang GmbH, 2013. Print.

- ↑ Kosta, Peter. “Empty Categories, Null-Subjects and Null-Objects and How to Treat Them in the Minimalist Program.” Linguistics in Potsdam 2.3 (1995/1996): 7-38. Web. 6 December 2013.

- 1 2 Carnie, Andrew. Syntax: A Generative Introduction. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. Print. 439.

- ↑ Carnie, Andrew. Syntax: A Generative Introduction. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. Print. 439.

- ↑ Carnie, Andrew. Syntax: A Generative Introduction. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. Print. 446.

- ↑ Carnie, Andrew. Syntax: A Generative Introduction. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. Print. 447.

- 1 2 Carnie, Andrew. Syntax: A Generative Introduction. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. Print.

- ↑ Cameron, Richard. "Pronominal and Null Subject Variation in Spanish: Constraints, Dialects, and Functional Compensation." Order No. 9227631 University of Pennsylvania, 1992. Ann Arbor: ProQuest. Web. 28 Nov. 2013.

- 1 2 3 Huang, C.-T.J. "PRO-drop in Chinese". The Null Subject Parameter(1989):185-214. Web. 11 Nov 2013.

- 1 2 Carnie, Andrew. Syntax: A Generative Introduction. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. Print. 340.

- ↑ Etsuro, Shima. "Two types of Wh-Features". Lingua (1999)107.3/4:189–206. Web. 17 November 2013.

- ↑ Sobin, Nicolas. Syntactic Analysis: The Basics. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. Print.

- ↑ Carnie, Andrew. Syntax: A Generative Introduction. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. Print.

- 1 2 de Villiers, Jill. "Empty categories and complex sentences: the case of wh-questions.." People Umass. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Oct. 2013.