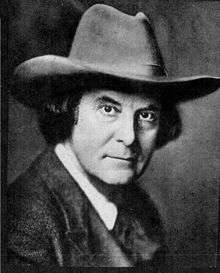

Elbert Hubbard

| Elbert Hubbard | |

|---|---|

Elbert Hubbard | |

| Born |

Elbert Green Hubbard June 19, 1856 Bloomington, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died |

May 7, 1915 (aged 58) Aboard the torpedoed RMS Lusitania in the Atlantic Ocean 11 miles (18 km) off the Old Head of Kinsale, Ireland |

| Occupation | Writer, publisher, artist, philosopher |

| Spouse(s) | Bertha Crawford Hubbard (divorced); Alice Moore Hubbard (1904–1915) (their death) |

| Children | Elbert Hubbard II (1882–1970), Sanford Hubbard (1887–1955), Ralph Hubbard (1885–1980) and Catherine (née Hubbard) Bryan (1896–1961) by Bertha; Miriam Elberta Hubbard (1894–1985) by Alice |

Elbert Green Hubbard (June 19, 1856 – May 7, 1915) was an American writer, publisher, artist, and philosopher. Raised in Hudson, Illinois, he had early success as a traveling salesman for the Larkin Soap Company. Presently Hubbard is known best as the founder of the Roycroft artisan community in East Aurora, New York, an influential exponent of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Among his many publications were the fourteen-volume work Little Journeys to the Homes of the Great and the short publication A Message to Garcia. He and his second wife, Alice Moore Hubbard, died aboard the RMS Lusitania when it was sunk by a German submarine off the coast of Ireland on May 7, 1915.

Early life

Hubbard was born in Bloomington, Illinois, to Silas Hubbard and Juliana Frances Read on June 9, 1856. In the autumn of 1855, his parents had relocated to Bloomington from Buffalo, New York, where his father had a medical practice. Finding it difficult to settle in Bloomington—mainly due to the presence of several already established doctors—Silas moved his family to Hudson, Illinois the next year.[1]:7 Nicknamed "Bertie" by his family, Elbert had two older siblings: Charlie, who was largely bed-ridden after a fall when he was young, and Hannah Frances, nicknamed "Frank" like her mother.[1]:10–11 Charlie died at the age of nine, when Elbert was three-and-a-half years old. Elbert also had three younger sisters who were named Mary, Anna Miranda, and Honor.[1]:11–12

The Hubbard children attended the local public school, a small building with two rooms that overlooked a graveyard. Thirty years later, Elbert described his schooling days as "splendid" and "tinged with no trace of blue.... I had no ambitions then—I was sure that some day I could spell down the school, propound a problem in fractions that would puzzle the teacher, and play checkers in a way that would cause my name to be known throughout the entire township."[1]:14 Mary would remember her older brother's role as a school troublemaker, noting that he "annoyed his teachers... occasionally by roaring inappropriately when his too-responsive sense of humor was tickled."[1]:15

Elbert's first business venture was selling Larkin soap products, a career which eventually brought him to Buffalo, New York. His innovations for Larkin included premiums and "leave on trial".[2]

Religious and political beliefs

I am an Anarchist. All good men are Anarchists. All cultured, kindly men; all gentlemen; all just men are Anarchists. Jesus was an Anarchist.

Elbert Hubbard, A Message to Garcia and Thirteen Other Things p.147

Hubbard described himself as an anarchist and a socialist.[3]:149 He believed in social, economic, domestic, political, mental and spiritual freedom.[3]:ii In A Message to Garcia and Thirteen Other Things (1901), Hubbard explained his Credo by writing "I believe John Ruskin, William Morris, Henry Thoreau, Walt Whitman and Leo Tolstoy to be Prophets of God, and they should rank in mental reach and spiritual insight with Elijah, Hosea, Ezekiel and Isaiah."[3]:i

Hubbard wrote a critique of war, law and government in the booklet Jesus Was An Anarchist (1910). Originally published as The Better Part in A Message to Garcia and Thirteen Other Things, Ernest Howard Crosby described Hubbard's essay as "The best thing Elbert ever wrote."[4]

Roycroft

His best-known work came after he founded Roycroft, an Arts and Crafts community in East Aurora, New York in 1895. This grew from his private press which he had initiated in collaboration with his first wife Bertha Crawford Hubbard, the Roycroft Press, inspired by William Morris's Kelmscott Press.[5] Although called the "Roycroft Press" by latter-day collectors and print historians, the organization called itself "The Roycrofters" and "The Roycroft Shops".[6]

Hubbard edited and published two magazines, The Philistine and The Fra. The Philistine was bound in brown butcher paper and featuring largely satire and whimsy. (Hubbard himself quipped that the cover was butcher paper because: "There is meat inside."[7] The Roycrofters produced handsome, if sometimes eccentric, books printed on handmade paper, and operated a fine bindery, a furniture shop, and shops producing modeled leather and hammered copper goods. They were a leading producer of Mission Style products.

Hubbard's second wife, Alice Moore Hubbard, was a graduate of the New Thought-oriented Emerson College of Oratory in Boston and a noted suffragist. The Roycroft Shops became a site for meetings and conventions of radicals, freethinkers, reformers, and suffragists. Hubbard became a popular lecturer, and his homespun philosophy evolved from a loose William Morris-inspired socialism to an ardent defense of free enterprise and American know-how. Hubbard was much mocked in the press for "selling out".[8]

He received much criticism for saying that prison is, "An example of a Socialist's Paradise, where equality prevails, everything is supplied and competition is eliminated."[9]

In 1908, Hubbard was the main speaker at the annual meeting of The Society in Dedham for Apprehending Horse Thieves.[10] Before he died, Hubbard planned to write a story about Felix Flying Hawk, the only son of Chief Flying Hawk. Hubbard had learned about Flying Hawk during 1915 from Major Israel McCreight.[11]

In 1912, the famed passenger liner RMS Titanic was sunk after hitting an iceberg. Hubbard subsequently wrote of the disaster,[12] singling out the story of Ida Straus, who as a woman was supposed to be placed on a lifeboat in precedence to the men, but refused to board the boat.[lower-alpha 1] Hubbard then added his own commentary:

"Mr. and Mrs. Straus, I envy you that legacy of love and loyalty left to your children and grandchildren. The calm courage that was yours all your long and useful career was your possession in death. You knew how to do three great things—you knew how to live, how to love and how to die. One thing is sure, there are just two respectable ways to die. One is of old age, and the other is by accident. All disease is indecent. Suicide is atrocious. But to pass out as did Mr. and Mrs. Isador Straus is glorious. Few have such a privilege. Happy lovers, both. In life they were never separated and in death they are not divided."[12]

Conviction and pardon

At the beginning of World War I, Hubbard published a great deal of related commentary in The Philistine and became anxious to cross the ocean, report on the War and interview the Kaiser himself. However, Hubbard had pleaded guilty on January 11, 1913, in the court of U.S. District Court Judge John R. Hazel for violating Section 211 of the penal code.[13] Hubbard was convicted on one count of circulating "objectionable" (or "obscene") matter in violation of the postal laws.[14] Sentence was suspended on five additional counts during good behavior, but Hazel fined Hubbard $100, and the federal conviction resulted in a revocation of the publisher's civil rights.[15]

Hubbard requested a presidential pardon from William Howard Taft, but the administration discarded the request as "premature".[15] When his application for a passport was denied in 1915, Hubbard went directly to the White House and pleaded with Woodrow Wilson's personal secretary, Joseph P. Tumulty. At the time, the President was in the midst of a cabinet meeting, but Tumulty interrupted and, as a result, the Secretary of State (William Jennings Bryan) and Attorney General Thomas Gregory were also able to hear of Hubbard's situation and need.[16]

The pardon was found to be appropriate, and Hubbard's clemency application process lasted exactly one day.[17] Seventy-five percent of those petitioning for clemency during that fiscal year were not so fortunate; their requests were denied, adversely reported, or no action was taken.[17] On receiving his pardon, Hubbard obtained a passport and, on May 1, 1915, left with his wife on a voyage to Europe.[lower-alpha 2]

Death

Coincidentally, a little more than three years after the sinking of the Titanic, the Hubbards boarded the RMS Lusitania in New York City. On May 7, 1915, while at sea 11 miles (18 km) off the Old Head of Kinsale, Ireland, the ship was torpedoed and sunk by the German U-Boat U-20.

In a letter to Elbert Hubbard II dated March 12, 1916, Ernest C. Cowper, a survivor of this event, wrote:[19]

I cannot say specifically where your father and Mrs. Hubbard were when the torpedoes hit, but I can tell you just what happened after that. They emerged from their room, which was on the port side of the vessel, and came on to the boat-deck.Neither appeared perturbed in the least. Your father and Mrs. Hubbard linked arms—the fashion in which they always walked the deck—and stood apparently wondering what to do. I passed him with a baby which I was taking to a lifeboat when he said, 'Well, Jack, they have got us. They are a damn sight worse than I ever thought they were.'

They did not move very far away from where they originally stood. As I moved to the other side of the ship, in preparation for a jump when the right moment came, I called to him, 'What are you going to do?' and he just shook his head, while Mrs. Hubbard smiled and said, 'There does not seem to be anything to do.'

The expression seemed to produce action on the part of your father, for then he did one of the most dramatic things I ever saw done. He simply turned with Mrs. Hubbard and entered a room on the top deck, the door of which was open, and closed it behind him.

It was apparent that his idea was that they should die together, and not risk being parted on going into the water.

The Roycroft Shops, managed by Hubbard's son, Elbert Hubbard II, operated until 1938.[20]

Posthumous renown

Owing to his prolific publications, Hubbard was a renowned author. Contributors to a 360-page book published by Roycrofters and titled In Memoriam: Elbert and Alice Hubbard included such celebrities as meat-packing magnate J. Ogden Armour, business theorist and Babson College founder Roger Babson, botanist and horticulturalist Luther Burbank, seed-company founder W. Atlee Burpee, ketchup magnate Henry J. Heinz, National Park Service founder Franklin Knight Lane, success writer Orison Swett Marden, inventor of the modern comic strip Richard F. Outcault, poet James Whitcomb Riley, Nobel Peace Prize recipient Elihu Root, evangelist Billy Sunday, intellectual Booker T. Washington, and poet Ella Wheeler Wilcox. Another book which was written by Hubbard is titled Health and Wealth. It was published in 1908 and includes many short truisms that are in line with the Truth movement and Transcendentalists concerning using intelligence to rid one of fear and, thus, to gain health and happiness which results in true wealth through service to others.

After his death, Hubbard's Message to Garcia essay was adapted into two movies: the 1916 silent movie A Message to Garcia and the 1936 movie A Message to Garcia.

In popular culture

Mack Bolan, the main character of Don Pendleton's fiction series Executioner, frequently cites as inspiration a Hubbard quote, "God will not look you over for medals, diplomas, or degrees – but for scars."[21][22]

At the end of "Rabbit's Feat", a 1960 Bugs Bunny and Wile E. Coyote cartoon, Bugs quotes Hubbard by saying, "Don't take life too seriously. You'll never get out of it alive."

The phrase "The graveyards are full of indispensable men" may have originated with Hubbard.[23]

A quote of Hubbard's from his biography of American automotive developer John North Willys, "Do nothing, say nothing, and be nothing, and you’ll never be criticized." is often misattributed to Aristotle.[24]

Selected works

- Forbes of Harvard (1894)

- No Enemy But Himself (1894)

- Little Journeys to the Homes of the Great (1895–1910)

- The Legacy (1896)

- A Message to Garcia (1899)

- A Message to Garcia and Thirteen Other Things (1901)

- Love, Life and Work (1906)

- White Hyacinths (1907)

- Health and Wealth (1908)

- The Mintage (1910)

- Jesus Was An Anarchist (1910), also published as The Better Part

- Elbert Hubbard's Scrap Book (1923)

- The Note Book of Elbert Hubbard (1927)

- The Philosophy of Elbert Hubbard (1930)

See also

- When life gives you lemons, make lemonade – a proverbial phrase based on a quote by E. Hubbard

Notes

- ↑ Hubbard wrote of Mrs. Straus saying, "Not I—I will not leave my husband. All these years we've traveled together, and shall we part now? No, our fate is one."[12] Three years later, Hubbard and his wife both died in the sinking of the Lusitania.

- ↑ The original copy is on display at the Elbert Hubbard–Roycroft Museum.[18]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Champney, Freeman (1983). Art & Glory: The Story of Elbert Hubbard. Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-295-1.

- ↑ "A Brief History of the Larkin Company". The Larkin Collection. The Monroe Fordham Regional History Center. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Hubbard, Elbert (1901). A Message to Garcia and Thirteen Other Things.

- ↑ Hubbard, Elbert (1910). Jesus Was An Anarchist.

- ↑ Gallimore, Andrew (2006). Occupation: Prizefighter The Freddie Welsh Story. Bridgend: Seren. p. 159. ISBN 978-1-85411-395-5.

- ↑ Davis, Hilary. "The Roycroft Community: 1894-1938". arts-crafts.com. The Arts & Crafts Society. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ↑ Bond, Guy Loraine (1962). Deeds of Men. Chicago: Lyons and Carnahan. p. 266.

- ↑ "The Standard Oil Company and Elbert Hubbard". Watson's Jeffersonian Magazine. 5 (1): 540–43. July 1910. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ↑ Hubbard, Elbert (June 1912). The Philistine, a Periodical of Protest - Volume 35. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ↑ Hubbard, Elbert. "A New Club!". The Fra (January to June 1909).

- ↑ McCreight, M. I. (1943). "The Story of Felix Flying Hawk: Rustler Victim". The Wigwam: Puffs from the Peace Pipe. Sykesville, Pa.: Nupp Printing Co. pp. 36–38.

- 1 2 3 Hubbard, Elbert (May 1912). "The Titanic". The Fra. IX (2).

- ↑ "Elbert Hubbard Guilty" (PDF). Rome Daily Sentinel. January 11, 1913.

- ↑ "The Conviction of Hubbard". Boston Evening Transcript. January 16, 1913.

- 1 2 Ruckman, P.S. (September 15, 2012). "Making O. Henry Proud: A Classic Pardon Tale". Pardon Power. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Hubbard Just Pardoned". New York Times. May 9, 1915.

- 1 2 Department of Justice (1915). Annual report of the Attorney General of the United States. p. 347.

- ↑ "President Woodrow Wilson Sealed the Fate of Elbert Hubbard". Roycroft Campus Corporation. May 8, 2007. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Elbert Hubbard Papers Manuscript Group #17" (PDF). Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved November 18, 2014. Also, Selected Writings of Elbert Hubbard. The Roycrofters. 1922. pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Via, Marie; Searl, Marjorie B. (1994). Head, Heart, and Hand: Elbert Hubbard and the Roycrofters. University Rochester Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-878822-44-4.

- ↑ Pendleton, Don (1978). Monday's Mob. Pinnacle Books. p. 166. ISBN 0523418159.

- ↑ Pendleton, Don (1979). Friday's Feast. Pinnacle. p. 79. ISBN 0-523-41883-3.

- ↑ O'Toole, Garson (November 21, 2011). "The Graveyards Are Full of Indispensable Men". Quote Investigator. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ↑ http://philosiblog.com/2013/07/12/to-avoid-criticism-say-nothing-do-nothing-and-be-nothing/

- Additional sources

- Hamilton, Charles Franklin. As Bees in Honey Drown; Elbert Hubbard and the Roycrofters (1973. South Brunswick: A.S. Barnes) ISBN 0-498-01052-X.

- Lane, Albert. Elbert Hubbard And His Work: A Biography, A Sketch, And A Bibliography (1901. The Blanchard Press) ISBN 0-554-84254-8.

- Leuchtenburg, William E. American Places: Encounters with History (2002. Oxford University Press) ISBN 0-19-515245-X.

- Walsdorf, Jack. Elbert Hubbard, William Morris's Greatest Imitator (1999. Yellow Barn Press)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Elbert Hubbard. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Elbert Hubbard |

- Works by Elbert Hubbard at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Elbert Hubbard at Internet Archive

- Works by Elbert Hubbard at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Elbert Hubbard at Find a Grave

- "Elbert Hubbard: An American Original", November 2009—PBS / WNED

- The Roycrofter Website

- The Elbert Hubbard papers at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin

- The Winterthur Library Overview of an archival collection on Elbert Hubbard.

- Hubbard Collection is located at the Special Collections/Digital Library in Falvey Memorial Library at Villanova University.