Eland Mk7

| Eland Mk7 | |

|---|---|

|

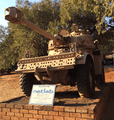

Reumech Eland at the Tempe School of Armour, Bloemfontein | |

| Type | Armoured Car |

| Place of origin | South Africa |

| Service history | |

| In service |

1962 – 1994 (South Africa)[1] 1967 - (other)[2] |

| Used by | See Operators |

| Wars |

Angolan Civil War Rhodesian Bush War 1981 Entumbane Uprising South African Border War Western Sahara War Second Congo War Chadian Civil War Northern Mali conflict Boko Haram insurgency |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Sandock-Austral |

| Designed | 1962[3] |

| Manufacturer |

Sandock-Austral Reumech OMC |

| Produced | 1964[3] – 1986[4][5] |

| Number built | 1,600[6] |

| Variants | See Variants |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 6 tonnes (6.6 short tons; 5.9 long tons)[7] |

| Length | 5.12 m (16 ft 10 in)[7] |

| length | 4.04 m (13 ft 3 in) (hull)[7] |

| Width | 2.01 m (6 ft 7 in)[7] |

| Height | 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in)[7] |

| Crew | 3 (commander, driver, gunner)[8] |

|

| |

Main armament |

90mm Denel GT-2 (29 rounds) 60mm K1 mortar (56 rounds) |

Secondary armament | 2x 7.62mm M1919 Browning machine guns[9] (2400 - 3800 rounds)[8] |

| Engine | General Motors 2.5 l (150 in3) inline 4-cylinder water-cooled petrol[9] |

| Transmission | 6-speed manual constant mesh[8] |

| Suspension | Independent 4X4; active trailing arms[8] |

| Ground clearance | 380 mm[8] |

| Fuel capacity | 142 litres[8] |

Operational range | 450 km[7] |

| Speed | 100 km/h[6] |

The Eland is an air portable[10] light armoured car based on the Panhard AML.[9] Designed and built by South Africa for long-range reconnaissance,[11] it mounts either a 60mm (2.4 in) breech-loading mortar or a Denel 90mm (3.5 in) gun on a very compact chassis.[9][12] Although lightly armoured, the vehicle's permanent 4X4 drive makes it faster over flat terrain than many tanks.[13]

Eland was developed for the South African Defence Force (SADF) in South Africa's first major arms programme since World War II, with prototypes completed in 1963.[14] By 1991, 1,600 examples had been built for home and export;[6] prominent foreign operators included Morocco and Zimbabwe.[2] Local overhauls incorporating lessons from internal operations have resulted in a vehicle capable of withstanding the unforgiving Southern African environment and highly mobile operational style of the SADF.[8]

Development history

Background

For many years the standard armoured car of the South African Defence Force was the Daimler Ferret, which was developed in the late 1940s and armed with a single general-purpose machine gun. By the mid 1960s, Ferret spares were becoming difficult to obtain, and its armament was obviously less than adequate. In 1961, South Africa accordingly secured a similar platform with a much wider range of armament installations: the French Panhard AML.[3] Between 1962 and 1964, Panhard approved a licence for the AML's domestic production in South African plants.[15] The result was the VA (Vehicle A) Mk2, first offered to the SADF's armoured car regiments and reconnaissance commands in 1964.[3] Bids were accepted from four local companies for the manufacture of 300 AMLs with working armament, along with another 150 turretless demonstrators; this contract was claimed by Sandock-Austral, now Land Systems OMC.[14]

Sandock VAs initially fared rather poorly; all 56 models furbished in 1966 were rejected by the South African Army. An extensive rebuild programme followed - the Panhards were returned to the manufacturer, completely disassembled, restructured, and trialled again.[6] These new vehicles claimed a local content of forty per cent but remained heavily bolstered by components imported from France in 1961.[14] Upon undergoing several upgrades to the steering (Mk2) and brakes (Mk3), each vehicle was also equipped with a custom fuel system;[13] the electric clutches were concurrently replaced by more conventional hydraulics (Mk4).[9] While South Africa's AMLs remained externally similar to their French counterparts, up to two-thirds of their design was of indigenous origin by 1967, the main part of that balance being a new water cooled inline-4 cylinder petrol engine installed in the Mk5.[6] Subsequent models were thus officially designated Eland.[3]

Layout of Eland variants are much the same. A driver is seated towards the front and the turret bolted near the centre, in addition to the transmission and turbocharged motor enclosed at the rear.[16] Operated by a crew of three, it houses a small and remarkably lightweight 4X4 frame with a height of 2.5 metres, a length of 5.12 metres, and a weight of 6 metric tons. Powered by a GM engine, Eland Mk5s boasted a 450-kilometre range and consumed 25 litres of fuel per 112.5 km.[8] Most were armed with the 60mm gun-mortar, and two 7.62mm Browning machine guns (Eland-60). The second most common version, Eland-90, was mounted with a 90mm gun. When first introduced, this weapon was more suited to a main battle tank, but in decades since wheeled fighting vehicles had become increasingly versatile. The SADF made extensive use of both, finding an Eland-60 particularly useful for reconnaissance and patrol during counter-insurgency operations.[8]

Service life

Elands now formed the mainstay of South African armoured units, although as early as 1969 SADF officials were discussing their replacement or supplementation with something more suited to countering tank warfare.[17] Having undergone extensive upgrade programmes in the early 1970s, there were now 369 Eland-60s and 131 Eland-90s under active service. Anticipating conventional military threats to South Africa from abroad, the SADF ordered another 356 vehicles and began fitting the existing fleet with ENTAC missiles for deployment in antitank roles.[17] This was followed swiftly by the introduction of the Eland Mk6 - Mk5 conversions of older models.[14] Between 1974 and 1975, up to 1,016 Mk6s were refurbished by Sandock-Austral.[14]

The vehicle was first tested in combat against Cuban and People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) forces[18] during Operation Savannah.[12] In late 1975, reports of shipments of Soviet T-34 and PT-76 tanks to the MPLA perturbed South African advisers then involved with the Angolan Civil War.[19] Accordingly, the State Security Council approved the deployment of 22 Eland-90s to Silva Porto in mid-October.[20] Elands were to acquire a fearsome combat reputation in Angola, where they earned the moniker "Red Ants" due to unorthodox but effective crew tactics and the lack of any equivalent MPLA hardware.[21] Nevertheless, crews found fighting capability constrained when operating on terrain better suited for tracked vehicles, and criticised the lowness of the body, which made sighting difficult over thick bush. Additionally, five were immobilised in hostile territory thanks to mechanical failure, at least three of them on roads.[17]

The Eland-90 continued to enjoy considerable success in SADF service, proving to be a robust and popular car with the Special Service Battalion[13] and 61st Mechanised Infantry Group.[11] During Operation Sceptic (1980), Operation Protea (1981) and Operation Askari (1983), several proved capable of eliminating Cuban T-34[22] and T-54/55 tanks[23] at close range.[24] The SADF began to dispense with its Elands in the mid-1980s, replacing them with the larger and notably more dependable Ratel-90.[17]

I turned to see one of our small, odd-looking Eland armoured ‘Noddy' cars with its long 90-millimetre gun barrelling towards us at almost top speed from across the chana...it turned nimbly, kicking up a cloud of dust as he came directly through our scattered line and then turned again, this time towards the tank. The little armoured car came to a quick stop right in the middle of the open ground about 80 metres from the tank, waited a couple of seconds and then fired one shot from [its] 90-millimetre with a loud bang. The shot was right on target. When the smoke drifted away the T-34's turret was lying off to one side and the open body was burning, belching dense black smoke.

South African paratrooper describes a standoff between an Eland and a T-34-85 during Operation Protea. It was common for armour contacts to be fought at extremely close range in the Angolan bush.[25]

Once employed only as a scout car, the Eland auspiciously doubled as a conventional reconnaissance asset, an assault gun, and an ersatz tank destroyer[8] - but its obsolescence was highlighted by several factors, namely a flammable petrol engine which was especially vulnerable to rocket-propelled grenades, and its four wheels limited off-road mobility.[19] The effectiveness of the low pressure 90mm gun against modern tanks was also questionable; at the Battle of Cuvelai in January 1984, Eland-90s' HEAT shells - barring a lucky shot - rarely penetrated the opposing T-55s without multiple hits.[26]

The final variant to be released was Eland Mk7, introduced in 1979.[14] It included new power brakes, a new transmission, a lengthened hull, and an extended turret for accommodating taller South African servicemen.[11] A domed cupola with vision blocks was also added, allowing commanders to see through a full 360 degrees.[14] An Eland Mk7's motor is fixed on rails to simplify maintenance; it can be changed in under forty minutes.[8] Some were immediately exported to Zimbabwe Rhodesia to replace the older Mk4s then in service with the Rhodesian Security Forces, while others went on to serve throughout the remainder of the South African Border War.[27] Eland's continued shortcomings, however, initiated a series of experiments at the Bloemfontein School of Armour to find a suitable replacement, resulting in the Rooikat: an eight-wheeled, diesel-engined, vehicle.[19] The Mk7, with its rudimentary fire control and lack of turret stabilisers, was no longer considered necessary. Over 1,033 Elands have now been retired from service or sold off to foreign governments and corporations;[28] the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) has adopted some 176 Rooikats in their place.[29]

Combat history

South African Border War

Operation Savannah

Affectionately known as "Noddy Cars" to their crews, SADF Elands were deployed extensively throughout the Angolan Civil War.[30] Under pressure from General Constand Viljoen and Jonas Savimbi, the first examples were flown in during Operation Savannah in August 1975 to reinforce South African advisers then instructing the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA).[20] UNITA still occupied Nova Lisboa, Angola's second largest city, but their MPLA rivals controlled eleven of the sixteen district capitals and were making gains with the assistance of Cuban armour.[19] The new Eland-90s and their experienced crews, however, were more than a match for anything the MPLA could muster.[31] The MPLA's armed wing, the People's Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola (FAPLA) encountered these vehicles first at Humbe and Rocadas; neither trained nor equipped to resist such firepower, most were compelled to withdraw northwards.[32] This disadvantage allowed the light, fast-moving Elands to fight a mobile war, seizing the initiative and keeping FAPLA constantly off balance.[32] Throughout Savannah SADF columns were able to cover 90 kilometres a day, even when the rainy season slowed momentum.[19] On December 11, 1975 Cuban general Abelardo Colomé Ibarra cited the Elands' superior manoeuvrability as being one of two major tactical problems facing the defending FAPLA forces, the other being their lack of effective artillery support.[33]

It was intended for Eland troops to merely support motorised infantry on roads, but since no other armour was available the South Africans deployed them as column spearheads.[32] This left the cars particularly open to Cuban or FAPLA ambush with RPG-7s, B-10 recoilless rifles, and rocket artillery.[17] At the Rio Quicombo for example, two RPGs bombarded the lead Eland, blowing off a wheel, disabling the main gun, and peppering the crew with shrapnel.[19] During the Battle of Ebo, a FAPLA recoilless rifle struck a command Eland, overturning it and damaging radio equipment. Unable to identify the weapon's position, another three Elands were shot out before they could engage, although at least one crew made it to safety.[34] When two more Eland-90s arrived, the Angolans retaliated with a BM-21 Grad, destroying a fifth vehicle.[34] A reserve squadron was called up; this time they silenced the recoilless rifle.[35] Damaged Elands which could not be extricated by the reserve were later claimed by FAPLA on site and towed away for propaganda purposes.[34]

Neither Cuba nor the MPLA fielded any vehicle matching the Eland, and their BRDM-2s bore little comparison.[17] Savannah's first armour-to-armour engagement was fought on a highway stretch about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from Catengue, when Eland-90s knocked out seven FAPLA armoured cars advancing on Nova Lisboa.[19] On 18 December 1975, another troop of Battle Group Orange encountered T-34s of the Cuban Army.[36] A single Eland swung forward and lobbed a 90mm round into the lead tank, destroying it and forcing the others to withdraw.[37]

Operations Reindeer and Sceptic

Elands were again mustered by the SADF for Operation Reindeer during the Cassinga Raid in May 1978.[38] Reindeer's western objective - consisting of nine South West African People's Organisation (SWAPO) forward operating areas in southern Angola - was assigned to Colonel Andre Liebenberg and Battle Group Juliet, predecessor to 61 Mechanised Infantry Battalion Group. Besides Juliet, led by Savannah veteran Frank Bestbier, Liebenberg had at his disposal motorised combat teams in new Ratel infantry fighting vehicles.[39] Since Ratels then lacked sufficient firepower to deal with heavier threats, 21 Eland-90s and 2 Eland-60s were allocated to support the mounted infantry.[19]

One Eland-90 troop was slated to lead the attack on the "Dombondola Complex", codenamed "Objective Vietnam": Juliet's largest SWAPO target, protected by a well-defended system of trenches and earthworks.[38] Three others were to be held in support, on the roads linking Cuamato to Chetequera.[19] Liebenberg's Eland-60s, meanwhile, functioned as security vehicles for a battery of BL 5.5-inch Medium Guns.[40] While Reindeer was a success, several important lessons were learned regarding the Eland's performance during combined arms maneuvers.[26] Despite multi-wheel drive for example, Elands stalled in mud as well as loose sand, leaving no alternative but to tow them out with heavier vehicles; a time consuming affair. Speed was frustratingly slow on broken terrain.[41] The petrol engine was also an issue, since it necessitated a separate logistics apparatus from the Ratels'.[26] These problems were countered in the short run by mating a Ratel chassis to an Eland's 90mm cannon - creating the Ratel-90, with its six wheels, longer operating range, and 72 stored rounds being more suited to mobile bush operations and cooperating well with existing fleets of the mechanised infantry.[26]

On 10 June 1980, South Africa launched Operation Sceptic, its largest armoured operation since World War II, against an insurgent command centre at Chifufua, Angola, as well as smaller SWAPO encampments at Mulola and Chitumbo.[32] An Eland squadron (designated Combat Team 3) backed by four Ratel sections and a sapper unit was drawn from 61 Mechanised to drive point during the SADF's advance on Objective "Smokeshell".[19] As Eland-90s retained the poorest momentum and left much narrower tracks than Ratels, their crews led the convoy the 250 kilometres to Chifuafua.[42] From there, Combat Team 3 was tasked with providing fire support for the assault on SWAPO's main headquarters complex and engaging any stragglers attempting to withdraw northwards.[43] Again, the Eland's cross-country inferiority became evident as the column advanced only at a maximum speed of 20 km/h. When progressing through thick vegetation this slowed to an unacceptable 10 km/h, Sceptic experiencing further delays as cars repeatedly bogged down in the sand.[44] Due to their limited range, many ran out of fuel and had to be towed behind Ratels.[45]

At some point before 3:45 PM, the first enemy equipment fell into SADF hands when an Eland troop overran and captured two ZPU anti-aircraft guns.[46] Contact was made with SWAPO shortly afterwards, and both sides opened up at point-blank range; vehicle crews found themselves unable to support the assault group while fighting for their own survival.[45] Some were even forced to use their main guns in close quarters, suppressing guerrillas at three hundred metres.[44] In attempting to establish the intended fire support base, Combat Team 3 withered an ambush by at least fifty insurgents but suffered no casualties, even when inadvertently towing its stalled Elands through the killzone.[47]

Operation Protea

SWAPO cadres and their Angolan hosts were undeterred by preceding SADF campaigns. Partisan recruitment continued in earnest, and the difficulties experienced in storming "Smokeshell" forced South African tacticians to recognise that conventional cross-border operations were intricate affairs.[45] Nevertheless, Operation Sceptic had demonstrated that pressure on the home front could be relieved with aggressive preemptive or counterstrike strategy. In August 1981, four mechanised battlegroups staged Operation Protea - converging on SWAPO camps at Ongiva and Xangongo. At least three were equipped with Eland-90s, the remainder of the force being bolstered by Ratels and Eland-60s (again seconded to an artillery troop).[45] Protea had three objectives: to disrupt SWAPO's logistical apparatus in southern Angola, to preempt further infiltration of South-West Africa, and to capture or destroy as much military equipment as possible. This offensive was destined to encounter an unexpectedly large presence of Angolan regular forces, who brought their heavy armour into offensive action for the first time.[48] In preparation for potential encounters with FAPLA T-34-85 tanks, elements of 61 Mechanised practised "firebelt" actions, integrating mutual support and specialised manoeuvres. It was, however, stripped of its Ratel-90 antitank platoon for Protea, necessitating a greater dependence on the Eland: a vehicle unable to keep pace with Ratels during rapid firebelts.[48]

South African forces advanced on 23 August, cutting Xangongo off from Ongiva and establishing a blocking force near Chicusse. They stormed into Xangongo at 1:25 PM the following day, though it was late afternoon before the battle intensified. This settlement was garrisoned by FAPLA's 19th Brigade, which included a T-34 company and mechanised squadron.[45] Although Elands were vulnerable to the T-34's 85mm gun, their vastly superior mobility and the experience of SADF crews made a considerable difference. Three tanks had been demolished by late afternoon.[45] Elands were also deployed with the blocking force on the main axis of the Xangongo-Cahama highway, where it was hoped that their speed on tarred surfaces could be better exploited.[48] They did not have to wait long. In the evening a sizeable FAPLA convoy, consisting of armoured personnel carriers, infantry, and artillery, was glimpsed fleeing towards Cahama. Upon identifying the point vehicle as a BRDM-2, a South African spotter ordered "skiet hom met ‘n 90," ("shoot it with a 90[mm]"). Hit by three rounds, the vehicle ignited. A number of trailing BTR-152s, GAZ-66s, and BM-21s were also captured or destroyed.[48]

The assault on Ongiva began with an air strike on 27 August, while artillery engaged in knocking out predetermined FAPLA or SWAPO targets. Angolan troops counterattacked on at least two occasions with T-34s, three of which were annihilated by concentrated fire from the Ratel or Eland-90 squadrons.[45] In hindsight, tanks played a relatively limited role in the defence. Most had been dug in for use as static artillery - firing from entrenched positions near FAPLA camps and installations. This restricted their trajectory. Moreover, the T-34s faced south; their crews were thus unable to counter South African armoured cars arriving from the north.[45]

Operation Askari

At the end of Operation Protea, South Africa had captured over 3,000 tonnes of ammunition, overrun some 38,850 square kilometres of Angolan territory, and inflicted serious casualties on SWAPO and FAPLA.[49] Most significantly, the SADF installed its own garrisons at Xangongo and Ongiva - leaving behind two companies detached from the South West African Territorial Force (SWATF), an Eland squadron, and the special forces of 32 Battalion. Throughout 1982 Eland-90s were a common sight on the roads around Xangongo, deterring SWAPO from reentering the town.[32]

By 1983, FAPLA had completed an exhaustive two-year retraining and reequipment programme, greatly increasing in size, sophistication, and competence under the eye of Soviet military advisors. Luanda was spending 35% of its budget on external defence, and Mikoyan MiG-21s were beginning to disrupt the traditional South African Air Force superiority. Within five months of Protea, Cuba had committed another 7,000 troops to Angola. They also brought T-54/55 tanks, which were more formidable than the antiquated T-34.[49]

In April South Africa began compiling intelligence on SWAPO plans to move an additional 1,000 guerrillas into the operational area, using the Cunene rainy season for cover.[45] Modelled after Protea, Operation Askari began on 20 December 1983: headed for insurgent staging areas identified by aerial reconnaissance, four battalion-sized combat groups crossed into Angola. Askari called for a single unit of Eland-90s, which were scraped together from Regiment Mooirivier and Regiment Molopo. Unlike past operations, their crews were predominantly reservists.[45] The Elands were assigned to Task Force Victor, which was to acquire the unfortunate reputation of being Askari's poorest element. Marshalled against them were four FAPLA brigades stationed at Caiundo, Cuvelai, Mulondo, and Cahama, or one-seventh of the Angolan Army. Soviet commander Valentin Varennikov, who was instrumental in directing the Angolan defence, was confident that "given their numerical strength and armament, the brigades...[would] be able to repel any South African attack".[50]

The SADF, however, had no intention of making frontal attacks that could be costly in lives or resources. Askari depended on being able to keep FAPLA at bay through air strikes, long-distance bombardment, and light probing. In keeping with this principle, Task Force Victor marched east through Mongua before harassing FAPLA's 11th Brigade at Cuvelai, their intended target. Angolan defenders responded with heavy artillery.[45] A disappointed Constand Viljoen warned that if no major successes were achieved before 31 December, the operation might not continue. But Cuvelai had been identified as a key location in SWAPO's upcoming monsoon offensive, and had to be neutralised before Victor could be withdrawn. A flurry of new orders were issued accordingly: probing actions were to cease, and the enemy attacked "forcefully" prior to the 31st. The SWAPO camps near the town were the objective: South African officers were confident that neither Angola nor two adjacent Cuban battalions nearby would intervene.[49]

In line with his new directives, Victor commandant Faan Greyling was instructed to advance from the northeast. But this route was barred by the Cuvelai River, which was in flood and complicated by the heaviest rains in living memory.[45] Predictably, the Elands got stuck as they struggled up the muddy banks of every stream. SWAPO was waiting for Victor in force behind artillery, sixteen minefields, and ZU-23-2 anti-aircraft guns.[49] Faulty intelligence also complicated the attack: FAPLA did come to SWAPO's assistance with 13 T-55 tanks.[45] As his men were poorly equipped with antitank weapons, Greyling's Eland-90s had to bear the brunt of the armoured thrust.[51][note 1] Their inadequate low velocity cannon had great difficulty against the T-55s, often dispensing multiple shells before penetrating the tanks' armour.[26] Crew tactics were to encircle single tanks with an Eland troop (four cars) and keep on shooting until their target burned.[48]

Sensing an opportunity to disengage, Greyling called off the attack, but it was too late. Exhausted by the intensity of the firefight and already demoralised by their repeated failures, the South Africans routed. Headquarters demanded he resume the advance—Greyling retorted he would not do so without coherent planning or reconnaissance.[53] It eventually fell to an overworked 61 Mechanised to complete the objective. Due to the higher profile of their Ratel-90s they could locate T-55s over dense vegetation before the Angolan gunners in turn spotted them, an advantage Elands did not possess.[54] The armoured cars succeeded in damaging five tanks on the river, which were captured and retained for inspection.[45] South Africa finally took what was left of Cuvelai on January 7.[49]

Later service

The mediocre performance of improvised tank destroyers at Cuvelai convinced Ep van Lill, commander of 61 Mechanised, that his men could no longer be asked to fight tanks with armoured cars. Van Lill informed General Viljoen that the Eland-90 simply could not stand up to the heavier protection and armament of T-54/55s.[45] "Tank busting" expended too much 90mm ammunition and fatigued recoil systems. As demonstrated during Askari, crew morale was also affected when ordered to take on T-55s in their vulnerable vehicles. This contradicted South African Armoured Corps (SAAC) doctrine, which was to fight tanks with tanks.[26]

A few weeks later, van Lill was vindicated when a squadron of British Centurions - modified in South Africa as the "Olifant Mk1" - were delivered to the 61 Mechanised base in Omuthiya.[26] Unfortunately, as Angola was not seen as a conventional threat to South-West Africa itself, the retention of tanks in that territory was not regarded as cost-effective and Olifant crews frequently rotated out.[45] During Operations Moduler, Hooper, and Packer, Ratel-90s were again used in the role of tank destroyers.[49]

Task Force Victor's performance during Askari left much to be desired. At SADF review meetings, the reservists involved were bluntly criticised as "the worst battle group in 82 Mechanised Brigade". More attention was devoted to improving reservist leadership and morale. Also noted was the antiquity of the Eland, which was beginning to hinder operations.[52] It was not deployed in Angola again.[45]

Rhodesian Bush War

Rhodesia, which unilaterally declared its independence in 1965 and, subsequently, the formation of its own republic in 1970, was the first foreign government to receive the Eland. At least twelve Eland-60s were delivered by South Africa in 1967. Another seven arrived in 1971.[2] These were handed over to the Rhodesian Air Force (RhAF), as sabotage was a widespread concern and airfield security considered imperative for the war effort.[55] Air Force crews were trained at the School of Armour in Bloemfontein, alongside their South African counterparts.[56] Their Eland-60s were later demonstrated for the Rhodesian Army, whose officials undertook the first order in 1975.[2] Thirty Eland-90s were delivered, and served with the Rhodesian Armoured Corps until the end of the country's long-running bush war.[27]

Shortly after the arrival of Elands at New Sarum Air Force Station, rivalries intensified between the armoured car personnel and the flying corps. Airmen were annoyed by the Eland-60s' fuel consumption, given that the necessary petrol was appropriated from their own stocks. Rhodesian parachute instructors mockingly referred to crew members as "Desert Rats": a running gag that culminated in ratlike caricatures appearing on vehicle doors. The unit eventually embraced the mascot and adopted "Desert Mice" as an informal callsign. Their motto, "Seek and Squeak", parodied the "Seek and Strike" maxim of No.4 Squadron, RhAF.[56]

Based out of King George VI Barracks in Salisbury, the Rhodesian Armoured Corps (RhACR) was formed as a reserve unit. It inherited Daimler Ferrets from 1 Reconnaissance Troop, Rhodesian Light Infantry, and some decrepit T17 Staghound scout cars of World War II vintage. Crew members completed a year's training in March 1974, undergoing basics as support infantry before 26 weeks of armour instruction. The following year they received the first shipment of Eland Mk4s.[2]

Rhodesian armoured doctrine called for Elands to be used in border patrol, convoy escort, picket duty at key junctures, and "showing the flag" - or creating a visible government presence - in remote areas. Reconnaissance was carried out on the same doctrine laid down by the British for Humber and Marmon-Herrington armoured cars during World War II. Movement behind foreign lines or areas heavily occupied by insurgents was based on Israeli mechanised doctrine for entering "occupied territories".[57] To compensate for their frequent lack of air, artillery, or even infantry support in dangerous regions such as the Honde Valley, RhACR crews developed tactics emphasising movement, speed, and offensive action. Late in the war, Rhodesian engineers proved that AP rounds fired from an AK-47 could penetrate an Eland's frontal armour, but they conceded that this disadvantage was offset by the vehicle's speed and weapon range.[27]

As the Elands had been procured from South Africa, local security forces initially disguised them with number plates registered to the South African Police (SAP), which had a presence on the Rhodesian border. This facade was abandoned after the police were recalled in 1976, though South African authorities - fearing the consequences of any escalation of conflict between Rhodesia and her neighbours - barred their deployment in external raids.[27] Nevertheless, the departure of the SAP made this unenforceable, and Rhodesia's Eland-90s were sent into Mozambique during Operation Miracle (1979). Under the command of American major Darrell Winkler, they spearheaded the assault on "Monte Cassino", a hillside defended by ZPU and ZU-23-2 anti-aircraft guns in the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) complex at New Chimoio. A counterattack by Mozambican tanks caused some anxiety, but the Rhodesians were able to disperse them with Ordnance QF 25-pounders and two Hawker Hunter jets without committing their armoured cars.[58]

Zimbabwe

Operation Miracle had been conventional ground warfare in all but in name, convincing the Rhodesian leadership that their insurgency was now being waged on a scale they could not hope to win.[59] Less than ten days after the raid, a constitutional conference on Rhodesia was held at Lancaster House and chaired by Lord Carrington. In attendance were representatives of both ZANLA and the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA), its rival militant wing, along with their respective political heads. The conference concluded after forty-seven plenary sessions with agreements on a new constitution for majority rule, arrangements for a transitional period preceding recognised independence, and a ceasefire on 15 December 1979. South Africa began withdrawing its support.[60]

On 18 April 1980, Rhodesia became the new Republic of Zimbabwe, with avowed Marxist Robert Mugabe as premier. Determining that any Elands remaining in the former Rhodesian Army pool must not be permitted to fall into Mugabe's hands, a South African fifth column recruited conspirators in the Zimbabwe Defence Forces to repossess the armoured cars. This attempt fell through when a senior Zimbabwean general officer backtracked on their agreement. He still had time to serve before qualifying for a pension and was not keen to provoke the regime.[61] The SADF remained understandably reluctant to leave their own sophisticated hardware with an army which might well become their future opponents, and explosive charges were uncovered in the Eland-90 fuel tanks later that year.[62]

Sporadic fighting broke out between ZANLA and ZIPRA militants in 1980, and again in 1981. Being relatively neutral in the inter-factional strife, late Rhodesian units such as the Zimbabwe Armoured Corps (ZACR) were prime candidates for maintaining order. In January 1981, ZACR was persuaded to dispatch a single troop of Eland-90s to 1 Battalion, Rhodesian African Rifles (RAR), then keeping the peace in Harare. The cars were manned by national servicemen and led by Sergeant "Skippy" Devine, an Australian veteran of the Rhodesian Light Infantry.[63] Their first action came at Glenville, Bulawayo, during the second Entumbane Uprising, when Zimbabwe's 13th Infantry battalion succumbed to infighting. In the absence of the unit's British instructors, the RAR was tasked with quelling the altercation. Late on 8 February 1981, Devine's Elands obligingly charged the 13th encampment and flattened several dissidents beneath their spinning wheels.[63] Three days later, ZIPRA reinforcements in the form of BTR-152s were spotted approaching Bulawayo. Devine was ordered to intercept and destroy them. He was joined by the RAR's support company in infantry fighting vehicles.[62] The Elands promptly identified and knocked out a BTR at an outlying intersection.[63] Taking up positions on the high ground overlooking Selborne Avenue, they stayed in place until two more BTRs attacked, firing indiscriminately with DShK machine guns. Both were destroyed by 90mm shells at two hundred metres.[63] Devine conducted a sweep of the area the next morning, capturing several ZIPRA T-34 tanks without resistance.[62]

At independence, Zimbabwe had inherited between 26 and 28[64] Eland-90s, which were integrated into a single squadron with the 6 remaining Air Force Eland-60s.[65] After Entumbane, these were deemed insufficient. The Defence Ministry wanted another three squadrons of armoured cars.[62] If the need arose each squadron could theoretically be attached to a brigade. More to the point, Elands were already suffering from poor maintenance and lack of spares.[27] General Solomon Mujuru tasked a five-man procurement team, including Bruce Rooken-Smith (commander of the ZACR) to find a suitable complement. They did review the Lynx turret, which was mounted on the Panhard ERC-90 and later versions of the Panhard AML, but there is no indication that Harare was interested in refurbishing its existing fleet or purchasing an updated AML.[62] Mujuru settled on Brazil's EE-9 Cascavel and the first models were commissioned by Mugabe in 1984. The Elands were still in service as late as the Second Congo War.[66]

Western Sahara War

Prior to the outbreak of the Western Sahara War, the Royal Moroccan Armed Forces (FAR) received relatively little modern armament, particularly from non-Francophone states. Meanwhile, the Polisario Front, intent on waging an armed struggle for Sahrawi independence, had stockpiled weapons from Algeria and seized additional equipment during raids on Moroccan forces. The hardware attrition rate spiralled upwards after the Madrid Accords and it quickly became apparent that new suppliers were needed to fill the bulk of FAR's needs. A gradual arms buildup in the Sahara began in 1976.[67] Financial assistance from Saudi Arabia allowed Rabat to tap a broad supply network: weaponry was obtained as far abroad as Iran, West Germany, and Belgium.[68] Orders for Panhard AML-90s were placed with France; although some did arrive in second-hand condition,[2] Panhard had long closed its production line and referred Morocco to South Africa.[19] The first Eland Mk6s[69] were clandestinely imported in 1976.[70] Others appeared with Ratels in the FAR after 1978.[68] They were accompanied by eight South African instructors for training Moroccan crews, though other personnel were expressly forbidden to approach them.[71]

Morocco grew more concerned with each successive FAR setback, and in September 1979 General Ahmed Dlimi adopted a new strategy of consolidating the occupation forces spread out across Western Sahara. Individual garrisons were mustered into tactical groups for massed search and destroy operations against Polisario guerrillas menacing Dakhla, Zag, and Tarfaya.[67] FAR's Elands were first sighted during Operation Imam, one such attempt to break the encirclement of Zag. Over 30 were captured during the failed offensive and some were destroyed.[6] Domestic markings had been censored prior to export, but the vehicles were identified by an Afrikaans inscription on their intact fill caps.[19] Eland-90s remained a notable feature in El Aaiún's anniversary parades for several years to come.[72]

Other conflicts

South Africa supplied 40 Elands of unknown designation to the Ugandan People's Defence Force in the mid-1990s, along with Buffel mine-protected troop carriers. The cars likely entered service during the Second Congo War, and may have seen action with Ugandan armour at Kisangani.[66] They were later deployed against the Lord's Resistance Army.[73] Local media also published reports that Nelson Mandela's administration offered Elands to Pascal Lissouba before his loyalists were defeated by Angolan invaders in the Republic of the Congo Civil War. These claims could not be independently verified.[74] Another source maintains that the original Congo order was placed in 1994 and only one was delivered.[75]

At least 100 Eland-90s and 20 Eland-60s were emptied from SANDF surplus in 1999 and handed to a Belgian defence contractor (Sabiex) for resale.[76] In September 2006, it emerged that President Idriss Déby of Chad was negotiating their purchase. The first 40 were delivered via France on March 3, 2007 and soon blooded in the fighting against a rebel faction encroaching on Adré.[77] While Belgium reported the 1999 deal to the United Nations Register of Conventional Arms, it neglected to offer any details regarding Chad. Sabiex could neither confirm nor deny the sale to Amnesty International. The Wallonia Directorate for Arms Licences merely recalled authorising export to a buyer in France, without any restrictions as to further sales or transfers.[78] Chad has since used its Elands on routine patrols near the Sudanese border, and against Islamic radicals in northern Mali.[79][80]

Because the Eland is regarded as a cheap alternative to improvised technicals in areas where climate, terrain, and lack of support infrastructure or technical skill forestall the operation of large heavy armour forces, it has remained popular with sub-Saharan armies and insurgent groups.[10]

Description

Eland hulls are constructed of a welded homogenous steel that provides moderate protection against grenade fragments, antipersonnel mines, and light weapons.[27] The driver is seated at the front of the vehicle and is provided with a one-piece hatch cover that swings to the right. He has a total of three integral periscopes, which may be replaced by passive infrared or night vision equipment for driving in darkness.[16] The turret is in the centre of the hull, where two other crew members are alternatively seated by variant. The rear power plant is completely enclosed in the hull with air intake and exhaust openings safeguarded through a ballistic grille conceding unrestricted air passage.[1]

An Eland's gearbox has one reverse and six forward gears.[13] It is crosswise, coupled to both sides of the bevel pinion.[16] Drive is transmitted from the gearbox to two lateral transfer boxes via pinions to the rear wheels and drive shafts that follow the hull to the front wheels. The shafts have extra universal joints beneath the turret.[9] Each shaft drives a second cam type differential which bar either of the two wheel pairs from exerting a speed radically different from the other. In this respect Elands are less likely to experience transmission fouls and tyre wear than other armoured cars with a single central differential.[81] The Panhard electric clutch, a major stumbling block for inexperienced drivers,[19] has been replaced by a more concurrent hydraulic system for easier maintenance and reduced crew training time.[9]

Also noteworthy is the independent suspension consisting of coil springs and hydropneumatic shock absorbers on trailing arms in the wheel mechanism; South Africa later adopted this design for the Rooikat.[82] All four wheels are of the split rim type and fitted with Dunlop 12.00x20 tyres.[83] There are two hydraulic braking systems, one for the front and one for the rear.[16]

External

A squat, four wheeled, vehicle, the Eland slopes downwards at the front and less prominently at the rear. There are large semicircular wheel arches, which are obscured by storage bins adjacent to each rear wheel. Sand channels are stowed across the front of the hull, with headlamps located on either side of the towing shackle, beneath the channels. There are three periscopes over the driver's position. Turrets are shallow and rounded, with sloping sides and a prominent sighting periscope to the right. There is a domed cupola over the commander's hatch.

Variants

Eland-60

Modelled after Panhard's AML HE-60-7, the Eland-60 was the first Eland variant to enter service.[2] It is armed with twin 7.62mm machine guns on the left and a single 60mm mortar on the right. Unlike its French predecessor, only one machine gun is mounted coaxially in the turret.[11] A second was typically carried on a pintle for anti-aircraft use.[9] The mortar has an elevation of +75° and a depression of -11°.[84] A single type of mortar is available: the Hotckiss-Brandt CM60A1, produced under licence as the Model K1.[85] It can be fired on a flat trajectory and is effective up to 300 metres in the direct role, or 1,700 metres in the indirect role.[16] No more than 56 rounds of 60mm and 3,800 rounds of 7.62mm ammunition are carried.[11] South African crews usually stored 44 mortar bombs per vehicle.[9]

Eland-60s have a rounded turret with a large, dual-piece, hatch cover opening front and rear. When needed it could accommodate four ENTAC missiles, two of which slide out of external rails to be launched.[16]

Eland-90

Modelled after Panhard's AML H-90, the Eland-90 functioned as a fire support platform and assault gun. In this role it was easy to underestimate.[13] During combat against tanks, its biggest edge was superior mobility, although this was diminished somewhat by the lack of a stabilised cannon.[45] Eland-90s are equipped with a Denel GT-2 90mm gun; a coaxial 7.62mm machine gun is also mounted to the left of the main armament.[84] The GT-2 has an elevation of +15° and a depression of -8°.[16] Turret rotation is manual and takes approximately twenty seconds. A gunner is seated on the right and has a one-piece hatch cover. The loader or commander is on the left of the gun and a single hatch cover provided for the commander.[16] Total ammunition capacity is 29 rounds of 90mm and 2,400 rounds of 7.62mm.[11]

When needed, Eland-90s could accommodate two ENTAC or SS.11 missiles, both of which slide out of external rails to be launched.[16]

Eland-20

The Eland-20 was a base Ratel's turret atop the Eland chassis. It is fitted with a 7.62mm machine gun and 20mm GI-2 (M963 F2) autocannon offering an elevation of +38° and a depression of -8°. The 20mm cannon has a cyclic rate of fire of 750 rounds per minute.[84] If required, another 7.62mm machine gun can be mounted on the turret roof.[16]

Destined for export, Eland-20s were marketed primarily to Morocco.[2] At least 18 of Ireland's AMLs were also upgraded to this standard by South Africa and redesignated "AML H-20".[86]

Other variants

In 1994, an Eland was showcased with a turbocharged diesel four-cylinder powerpack developing 103 hp at 4,000 rpm. Apart from the new engine, other changes were made to enhance performance in tropical climates. These included modified air conditioning and cooling systems.[14] Reumech OMC - then a subsidiary of Vickers - marketed the design as Eland Mk7 Diesel Turbocharged, or simply "Eland Mk7 DT". An estimated 200 Mk7s were haggled from the SANDF for diesel conversion.[14]

Mechanology Design Bureau, another South African firm, has proposed removing the Eland-90's turret altogether and replacing it with a giant cupola. This relieves ground pressure considerably, allowing for a vast electronic surveillance suite.[87]

Various demonstrators have been built at the SANDF School of Armour utilising an Eland drive train, suspension, or chassis. Examples include an armoured personnel carrier resembling the Panhard M3 and an 8X8 Rooikat prototype.[3]

Armament and ammunition

The modular design of Eland weapon systems allows manufacturers to update or downgrade armament with ease according to prospective clients' wishes.[14] Ranging is manual and Eland-90s assisted by a non-stabilised optical fire control system.[88]

Like the AML, the Eland is equipped with a two-person turret. The original Eland-60 had an unusual combination of the 60mm K1 mortar and two medium, or one heavy, machine guns - a combination inspired by French experiences in the Algerian War.[81] The mortar weighs 75 kg and is 1.8 metres long. Maximum effective range of the K1 as produced by Denel Land Systems is stated to be 1,700 metres.[84] An Eland-60 was always present in every South African support troop due to the effectiveness of its illumination bombs during night operations.[89]

It was the SAAC which first recommended an AML with heavier armament: they were then looking for a fire support platform to complement the Alvis Saracen.[90] Due to parts compatibility the Alvis Saladin was an obvious initial choice. Nevertheless, the AML licence had already been purchased, so there were obvious advantages in filling the same role with an existing vehicle. Panhard's response was the AML H-90.[90]

The 90mm gun, which fires fin-stabilised HEAT-T and High-explosive projectiles, is heavier than that mounted in the Saladin and provides the Eland with a very potent form of armament, considering its small size and speed. It weighs 380 kg and has a double baffle muzzle brake.[91] With the muzzle brake, it measures 4.1 metres in length.[84]

| Type | Model | Weight, kg (catridge/projectile) | Filler | Muzzle velocity, m/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEAT-T | OCC F1 | 7.077 / 3.65 | RDX/TNT, 670g | 760 |

| HEAT-TP | TP-T BSCC 90 F1 | 7.077 / 3.65 | Aluminum, tracer | 760 |

| HE | OE F1 | 8.662 / 5.27 | RDX/TNT, 945g | 650 |

| WP-SMK | OFUM F1 | 9.07 / 5.4 | White phosphorus, 800g | 650 |

| Canister | Canister GT-2 | - | 1100 lead spheres, 4 kg | 450 |

| Blank | Blank cartridge, 90mm F1 with shortened primer | 3.4 / - | - | - |

Effective range of the Denel GT-2 is stated to be 2,200 metres (HE).[84] The HEAT-T round will penetrate 320mm of armour at a zero angle of incidence or 150mm of armour at a 60° angle of incidence.[16] A locally manufactured fin-stabilised, shaped charged, projectile was also under development in 1976. The complete round weighs 7 kg of which the projectile itself weighs 3.65 kg.[16] The complete round is 654mm in length with the projectile being 500mm in length.[92] This round has an m/v of 750 m/s and a maximum velocity of 760 m/s, and effective range is given as 1,200 metres.[84]

Doctrine

The Eland's first combat deployment to the Caprivi Strip revealed major flaws in South African armour doctrine. Firstly, the SAAC learned that significant swathes of Namibian (and Angolan) terrain were not ideal conditions for military vehicles. Caprivi had thick bush which restricted movement, turret traverse, and visibility. It also confounded textbook formations. Second, Eland crews were trained on the arid flats of Bloemfontein and Walvis Bay. The conditions they encountered were very much unlike anything the SADF had prepared them for.[54]

Much was learned from Elands' performance in Operation Savannah. Their ability to move so swiftly over tar and packed gravel surprised FAPLA on multiple occasions.[13] They were also rather silent; a quiet petrol engine enabled stealth during ambush or evasive manoeuvres.[54] Furthermore, the Eland-90 proved that it was powerful enough to defeat the heaviest armour ranged against it, the Soviet T-34.[37] Savannah was the SAAC's first experience of mobile warfare in the Angolan bush, creating a laboratory where new tactics could be tested.[45]

According to the South African Military College at Voortrekkerhoogte, which clearly recognised the Eland's weakness in attrition warfare, SADF doctrine was to be "based on not to hold ground but to create the design of battle in such a way that you would lure the enemy into killing ground and then [with] the superiority of fire and movement, you would kill him completely." Factors such as rapid movement, striking from the flank, surprise and confusing the enemy with continuous manoeuvring thus became integral components in the new SAAC.[45] That Voortrekkerhoogte was worried about the Eland's light construction was apparent. It subsequently issued a requirement for a "heavy armoured car" and grafted support infantry into the existing squadrons to deal with the threat posed by RPGs.[89] Due to lack of space in an Eland to accommodate support troops, infantry mobility vehicles were called for. The SADF experimented with Land Rovers, Bedford RLs, and Unimog trucks before United Nations Security Council Resolution 418 further limited their choices. There were logistical incentives for adopting the Panhard M3, which shared many interchangeable parts with the Elands, but this notion was rejected: Pretoria wanted a true MRAP. After dozens of trials and modifications the Buffel was finally born.[89]

Eland squadrons operated on the troop (platoon) level in operational areas: one was assigned to virtually every major settlement (i.e. Rucana, Ondangwa, Eenhana, Katima Mulilo, etc.).[93] There were four Elands in a troop - Bravo Car, Alpha Car, Charlie Car, and Delta Car. Alpha and Charlie were the troop sergeant and leader respectively. Bravo was always an Eland-60. Delta was the additional option: either a second Eland-60[54] or a support infantry Buffel.[89] This provided an excellent mix of direct and indirect fire to troop commanders.[54] Bravo could release illumination bombs for night attacks or create a smokescreen. Charlie and Alpha laid down suppressive fire. If present Delta infantry debussed and attacked on foot from the nine o'clock position. Communication in the troop was essential, as fire had to be lifted once Delta moved to target.[89]

The armoured car troop was expected to operate independently. Its own crews carried out repair and recovery with limited resources. Operations were dictated by the amount of fuel, ammunition, water and ration that could be carried per vehicle.[89] The Eland's easy maintenance allowed them to operate on makeshift repairs in the field for up to seven days, hunting SWAPO cadres by day and forming open laagers by night.[54]

One of the first major breakthroughs of the late 1970s was the development of the Ratel. Three years after Springfield-Bussing built the first prototype in 1974, Magnus Malan reported to Parliament that the Ratel was "successfully industrialised".[45] Ratels replaced Buffels in support troops and by 1982 all armoured car regiments had been retrained to depend on mechanised infantry during conventional operations.[89] A second watershed came when twelve junior officers and senior noncoms underwent training as tank commanders in the Israeli Defense Forces, which had amassed considerable experience with mobile mechanised warfare. Officers who attended courses at the IDF combat school included the later commanders of 61 Mechanised, including Gert van Zyl and Ep van Lill.[45] The acquired expertise in armour tactics was implemented in SAAC curricula and manuals, replacing the archaic British doctrine of World War II. Commands became more concise, emphasis shifted to reaction speed, and evaluation methods improved substantially. Nevertheless, the SAAC defeated the purpose of Israeli tank drills by applying them directly to armoured cars, setting a trend that continued throughout the border war.[54]

Throughout the 1980s, Elands played a supporting role for the Ratel-mounted mechanised combat groups. Specific infantry battalions such as 61 Mechanised also held generic platoons of Eland-90s or Ratel-90s as an antitank reserve.[45] The latter was preferred, as Elands experienced difficulty observing other forces in thick bush. Spotting tanks was a particular problem. Their crews had an even chance of noticing FAPLA T-54/55s, which also had low profiles. This poor visibility in vegetation also complicated command and control, frustrating both driver and troop leader to no end.[54]

Whenever T-55s appeared on the battlefield, they caused anxious moments for the Eland.[54] The tanks boasted stabilised cannon, so they could fire on the move, whereas Eland-90 crews stopped to make their final ranging calculations before they could shoot.[45] Their inferior armament meant that Elands had to close in on a tank to eliminate it, which demanded considerable skill.[26] When possible gunners aimed for the rear, flank, or a vulnerable margin beneath the turret front.[45] Naturally the tank would also turn to avoid exposing its softer armour, so expert manoeuvring was required before they could get behind a T-55 and destroy it from there.[45]

Eland-90 troops always identified one tank as a priority target. Then, when the chance came, the Elands fired simultaneously—knocking out the tank. To avoid being hit between volleys, they had to keep moving.[48] This protocol was derived from SADF experience fighting T-34s and later applied to T-55s. Armoured car commanders believed it wouldn't have fared well against T-62s.[54] Eland-90s struggled in big, dense, bushes while attempting to carry out their usual tactic during Operation Askari[51] and were hereafter deemed unfit for high intensity campaigns.[89]

Survivors

South Africa formally retired its Eland-90 fleet in 1994.[1] The last SANDF exercise involving Elands of any description was held in 1996.[94] Of the 1,200 still accounted for in 1991, only 235 remained by 1998.[95] A statistic released by the Department of Defence in 1997 confirmed that Elands valued in excess of 41.3 million rand had been scrapped.[96] In October 2005, all the SANDF's remaining Elands were offered for sale.[97] Tenders for Eland-90s were still available in 2009.[98]

In January 2005, two Elands at the South African National Museum of Military History were repossessed and impounded by the SANDF.[99] Government records suggested they had been marked off for disposal some time prior.[100] Why the vehicles were maintained at the museum without the SANDF's apparent knowledge remains a mystery.[101] In July 2015, they were finally returned and overhauled by Denel at its own expense.[102]

Both the South African Armour Museum[3] in Bloemfontein and Sandstone Estates[9] in Ficksburg have preserved at least one Eland-90 and Eland-60 apiece. Others survive on SANDF bases as gate guardians.[1] Four armoured units are known to have retained individual Eland-90s for ceremonial purposes: 1 Special Service Battalion,[103] the Umvoti Mounted Rifles,[104] Regiment Mooirivier,[105] and Regiment Oranjerivier.[106] These vehicles participate in parades, public exhibitions, and fire gun salutes during special occasions, such as the anniversary of the South African Armoured Corps.[107] Turretless Elands modified with ring-mounted handrails are still used for transporting SANDF dignitaries on parade grounds during official inspections.[108][109]

An Eland-90 was sold at a private auction in Portola Valley, United States, on July 11–12, 2014.[110] Another Eland was sold to Jordan by an unidentified supplier in the United Kingdom the following year, possibly for exhibition at the Royal Tank Museum in Aqaba.[111] Other foreign museums known to possess Elands in their collections include the Gweru Military Museum in Zimbabwe[112] and the Sahrawi People's Liberation Army Museum in Algeria.[113]

For several decades, an Eland captured by FAPLA during Operation Savannah was publicly displayed in a square near the centre of Luanda.[114] This vehicle has undergone at least one restoration and now resides at the Angolan Museum of the Armed Forces.[115]

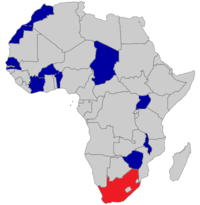

Operators

Benin - Beninese Army: 3[116] Eland-90s, supplied from unidentified source in 2010.[117] Beninese crews schooled by 1er RHP, France.[118]

Benin - Beninese Army: 3[116] Eland-90s, supplied from unidentified source in 2010.[117] Beninese crews schooled by 1er RHP, France.[118] Burkina Faso - Burkinabe Army: 4 Eland-90s, supplied from unidentified source in 2006.[2]

Burkina Faso - Burkinabe Army: 4 Eland-90s, supplied from unidentified source in 2006.[2] Chad - Chadian Ground Forces: 82 refurbished Eland-90s purchased from a Belgian firm in 2007.[119]

Chad - Chadian Ground Forces: 82 refurbished Eland-90s purchased from a Belgian firm in 2007.[119] Ivory Coast - Ivorian Army: Unidentified number of Elands.[120][121]

Ivory Coast - Ivorian Army: Unidentified number of Elands.[120][121] Malawi - Malawian Army: 13 Eland-90s purchased from the SANDF in 1994.[2]

Malawi - Malawian Army: 13 Eland-90s purchased from the SANDF in 1994.[2] Morocco - Moroccan Army: 60[2] Elands delivered in 1981; provided with instructors for training the Moroccan crews.[19]

Morocco - Moroccan Army: 60[2] Elands delivered in 1981; provided with instructors for training the Moroccan crews.[19] Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic - Polisario Front: Presumably captured from Morocco.[122]

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic - Polisario Front: Presumably captured from Morocco.[122] Senegal - Senegalese Army: 47 Eland-90s purchased in 2005.[28]

Senegal - Senegalese Army: 47 Eland-90s purchased in 2005.[28] Uganda - Ugandan Land Forces: 40 Elands purchased prior to the Second Congo War.[66]

Uganda - Ugandan Land Forces: 40 Elands purchased prior to the Second Congo War.[66] Zimbabwe - Zimbabwe National Army: 28 Eland-90s and 6 Eland-60s inherited from Rhodesian predecessor at independence in 1980.[64][65]

Zimbabwe - Zimbabwe National Army: 28 Eland-90s and 6 Eland-60s inherited from Rhodesian predecessor at independence in 1980.[64][65]

Former operators

South Africa - South African Army[11]

South Africa - South African Army[11].svg.png) South-West Africa - South West African Territorial Force: At least 40 Elands provided by the SADF;[123] deployed exclusively with 91 Brigade[124] and the 34th Kavangoland Battalion.[125]

South-West Africa - South West African Territorial Force: At least 40 Elands provided by the SADF;[123] deployed exclusively with 91 Brigade[124] and the 34th Kavangoland Battalion.[125] Rhodesia - Rhodesian Army: Up to 34[126] Eland-90s and Eland-60s acquired or on loan from South Africa, which initially limited their use in external raids. Disguised with South African Police licence plates prior to 1976.[27]

Rhodesia - Rhodesian Army: Up to 34[126] Eland-90s and Eland-60s acquired or on loan from South Africa, which initially limited their use in external raids. Disguised with South African Police licence plates prior to 1976.[27]

In popular culture

Eland-90s make an appearance in Call of Duty: Black Ops II, battling FAPLA troops during a fictitious engagement of Operation Alpha Centauri. A number are destroyed by T-62s outside Jamba in the protagonist's first mission, "Pyrrhic Victory".[127]

In the Larry Bond novel Vortex, an Eland squadron annihilates a Cuban T-62 company during a hypothetical SADF invasion of Namibia. The armoured cars are able to accomplish this by attacking from the rear; they later run low on fuel and are dug into hull down positions around Walvis Bay. This gives the T-62s an opportunity to close range and overrun them.[128]

Mothballed Elands are surreptitiously appropriated by a mercenary unit with the connivance of two corrupt SANDF officers in The Liberators, by Tom Kratman. At one point during the novel, an Israeli firm proposes upgrading the turrets with a 60mm hyper velocity gun. Eland-90s are eventually retained for their greater effectiveness against bunkers and fortifications.[129]

Gallery

-

Eland-90, frontal glacis

-

Eland-60, frontal glacis

-

Driving compartment

-

Gun selector switch box

-

Gunner's sight

-

Eland and T-55 of the Rhodesian Armoured Corps

-

Gate guardian at Tempe

-

Facility marker at Tempe

-

Eland-90 in the SA Armour Museum Lesakeng

-

.jpg)

Eland-90 in the Zimbabwe Military Museum

-

Chadian Eland on patrol in the Central African Republic

-

Elands outside Port Elizabeth drill hall

Notes and references

Annotations

- ↑ This confrontation took place during the general assault on the morning of December 31, 1983. The Eland-90s involved were escorting an infantry company, call sign Juliet 19, just outside Cuvelai when they encountered the T-55s.[52] South African and Soviet sources alike noted that several T-55s were penetrated by Eland-90 fire, presumably during this action, but did not elaborate on FAPLA's losses.[24][7]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Armoured Car, Eland Mk7/90 (RSA) (Gate exhibit), South African Armour Museum, Bloemfontein: South African National Defence Force, 2014

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Trade Registers". Armstrade.sipri.org. Retrieved 2013-06-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Lesakeng". South African Armour Museum. 2012-12-06. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ↑ Henk, Daniel. South Africa's armaments industry: continuity and change after a decade of majority rule (2006 ed.). University Press America. p. 164. ISBN 978-0761834823.

- ↑ Ogorkiewicz, Richard (2015). Tanks: 100 Years of Evolution. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781472806703.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Landgren, Signe. Embargo Disimplemented: South Africa's Military Industry (1989 ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 83–88. ISBN 978-0-19-829127-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Heitman, Helmoed-Römer. South African Armed Forces. Buffalo Publications 1990. ISBN 0-620-14878-0 p 44.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Heitman, Helmoed-Römer. South African Arms and Armour - A concise guide to armaments of the South African Army, Navy, and Air Force. Struik Publishers 1988. ISBN 0-86977-637-1 p 44-45.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Restoration of the Eland-60". Sandstone Estates. 2012-12-06. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- 1 2 "Fact file: Rooikat armoured car". Defence Web. 2010-01-21. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "AML-90". 61mech.org.za. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- 1 2 Bell, Kelly. Operation Savannah: Task Force Zulu & the Rommel of Angola. Modern War, 2006, Volume 1 Issue 4 p. 45.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "How Green We Were". Senteniel Projects. 2000. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Jane's Armour and Artillery, 2002, Volume 23 p. 244-245.

- ↑ Kaplan, Irving. Area Handbook for the Republic of South Africa. p. 739.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Foss, Christopher F. Jane's World Armoured Fighting Vehicles (1976 ed.). Macdonald and Jane's Publishers Ltd. p. 133. ISBN 0-354-01022-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Warwick, Rodney. Operation Savannah: A Measure of SADF Decline, Resourcefulness, and Modernisation. Scientia Militaria, 2012, Volume 40 Issue 3 p. 364-377.

- ↑ NEWSLETTER NO. 355 - JUNE 2008

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Steenkamp, Willem. Borderstrike! South Africa Into Angola 1975-1980 (2006 ed.). Just Done Productions. pp. 38–200. ISBN 1-920169-00-8.

- 1 2 Hamann, Hilton. Days of the Generals. pp. 30–35.

- ↑ Stander, Siegfried. Like the Wind: The Story of the South African Army (1985 ed.). Saayman & Weber Publishers. p. 92. ISBN 978-0797100190.

- ↑ Mobile firepower for contingency operations: Emerging concepts for US light armour forces

- ↑ Foss, Christopher F. The illustrated encyclopedia of the world's tanks and fighting vehicles: a technical directory of major combat vehicles from World War I to the present day (1977 ed.). Chartwell Books. p. 93. ISBN 978-0890091456.

- 1 2 Tokarev, Andrei; Shubin, Gennady. Bush War: The Road to Cuito Cuanavale : Soviet Soldiers' Accounts of the Angolan War (2011 ed.). Jacana Media (Pty) Ltd. pp. 128–130. ISBN 978-1-4314-0185-7.

- ↑ Korff, Granger. 19 with a bullet: A South African Paratrooper in Angola (2009 ed.). 30 Degrees South Publishers. p. 266. ISBN 978-1-920143-31-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Lessons of the Border War

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Rhodesian Armoured Car Regiment Uncovered". rhodesianforces.org. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- 1 2 "South African Arms Supplies to Sub-Saharan Africa" (PDF). SIPRI. January 2011. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ↑ South African Defence Review

- ↑ AllAtSea.co.za/army - Glossary of SA military terminology and slang

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero. Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-1976. pp. 301–305.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nortje, Piet (2003). 32 Battalion. Zebra Press. pp. 22–200. ISBN 978-1-86872-914-2.

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington and Africa, 1959–1976. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 319–320. ISBN 978-0-807-82647-8.

- 1 2 3 JUNE 2008 newsletter. South African Military History Society (Cape Town Branch), 2008, Volume 1 Issue 355.

- ↑ Battle for Ebo

- ↑ February 2007 newsletter. South African Military History Society (Johannesburg Branch), 2007, Volume 1.

- 1 2 Du Preez, Sophia. Avontuur in Angola: Die verhaal van Suid-Afrika se soldate in Angola 1975-1976. J.L. van Schaik. p. 182. ISBN 978-0627016912.

- 1 2 Into Angola - Operation Reindeer

- ↑ McGill Alexander, Edward (July 2003). "The Cassinga Raid" (PDF). UNISA. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ AUGUST 2005 newsletter. South African Military History Society (KwaZulu-Natal Branch), 2005, Volume 1 Issue 359.

- ↑ Breytenbach, Jan. Eagle strike!: the controversial airborne assault on Cassinga (2008 ed.). Manie Publishing. p. 193. ISBN 978-1909982307.

- ↑ Operation Sceptic

- ↑ Schoeman, Johan. Operation Sceptic: Battle Group 61's plan to capture Smokeshell. War in Angola Newsletter, 2012, Volume 3 Issue 23.

- 1 2 Schoeman, Johan. Operation Sceptic: The Operation. War in Angola Newsletter, 2012, Volume 3 Issue 24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Scholtz, Leopold (2013). The SADF in the Border War 1966-1989. Cape Town: Tafelberg. ISBN 978-0-624-05410-8.

- ↑ Schoeman, Johan. Operation Sceptic: The Attack on Smokeshell. War in Angola Newsletter, 2012, Volume 3 Issue 25.

- ↑ Schoeman, Johan. Operation Sceptic: The Attack on Smokeshell, Part 2. War in Angola Newsletter, 2012, Volume 3 Issue 26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Some remininiscenses on the operations conducted by Combat Team 3

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 George, Edward (2005). The Cuban Intervention in Angola, 1965-1991: From Che Guevara to Cuito Cuanavale. London: Frank Cass. pp. 22–233. ISBN 0-415-35015-8.

- ↑ Gleijeses, Piero (2013). Visions of Freedom: Havana, Washington, Pretoria, and the Struggle for Southern Africa, 1976-1991. United States: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 231–241. ISBN 978-1469609683.

- 1 2

- 1 2 Scheepers, Marius (2012). Striking Inside Angola with 32 Battalion. Solihull: Helion & Company. pp. 96–103. ISBN 978-1907677779.

- ↑ Regiment Mooirivier and South African transborder operations into Angola during 1975/76 and 1983/4. Historia, May 2004, Volume 1 Issue 49.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Jordaan, Evert. “The role of South African armour in South West Africa/Namibia and Angola: 1975-1989”. Journal for Contemporary History 31/3, December 1986. 54.

- ↑ Mills, Alan (2013). A Pathologist Remembers. Bloomington: Author House. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-4918-7882-8.

- 1 2 Salt, Beryl (2013). A Pride of Eagles: History of the Rhodesian Air Force. Solihull: Helion & Company. pp. 400–752. ISBN 978-1908916266.

- ↑ Kevin Douglas Stringer. Military Organizations for Homeland Defense and Smaller-scale Contingencies (2006 ed.). Praeger Security International. p. 99. ISBN 978-0275993085.

- ↑ Selous Scouts Operation Miracle September 1979

- ↑ Anthony Clayton. Frontiersmen: Warfare In Africa Since 1950 (1998 ed.). Routledge Books. pp. 57–65. ISBN 978-1857285253.

- ↑ JRT Wood. The War Diaries of Andre Dennison (1989 ed.). Ashanti Publishing. pp. 370–373. ISBN 978-0620135450.

- ↑ Stiff, Peter (2001), Warfare by other means. South Africa in the 1980s and 1990s., Alberton, South Africa: Galago, pp. 81–189

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stiff, Peter (June 2000). Cry Zimbabwe: Independence – Twenty Years On. Johannesburg: Galago Publishing. ISBN 978-1919854021.

- 1 2 3 4 Binda, Alexandre (November 2007). Heppenstall, David, ed. Masodja: The History of the Rhodesian African Rifles and its forerunner the Rhodesian Native Regiment. Johannesburg: 30° South Publishers. ISBN 978-1920143039.

- 1 2 Nelson, Harold. Zimbabwe: A Country Study. pp. 237–317.

- 1 2 Simon Baynham. Zimbabwe in transition (October 1992 ed.). Almqvist & Wiksell International. p. 240. ISBN 978-9122015086.

- 1 2 3 "Scramble for the Congo - Anatomy of an Ugly War" (PDF). ICG Africa. 2000-12-20. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- 1 2 Military Dimension of the Western Sahara Conflict

- 1 2 Michael Brzoska. Arms and Warfare: Escalation, De-escalation, and Negotiation (1994 ed.). University of South Carolina Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-1422352960.

- ↑ The Nation. JH Richards, December 20, 1980, Volume 230.

- ↑ Leo Kamil. Fueling the Fire: U.S. Policy & the Western Sahara Conflict (1987 ed.). Red Sea Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0932415233.

- ↑ Bulletin. Association of Concerned Africa Scholars; The Association, 1987, Volume 1 Collected Issues 20-25.

- ↑ The Middle East. IC Publications Limited, 1986, Collected Issues 135-145 p. 18.

- ↑ Camp, Steve; Helmoed-Römer, Heitman (November 2014). Surviving the Ride: A pictorial history of South African Manufactured Mine-Protected vehicles. Pinetown: 30 Degrees South. p. 239. ISBN 978-1928211-17-4.

- ↑ Reflections Efforts to deny the historical reality of the Holocaust

- ↑ Johannesburg Mail & Guardian, Volume 1: 8/18/97.

- ↑ Fact File: South African arms exports

- ↑ Double Misfortune - Deepening Human Rights Crisis in Chad

- ↑ Arms flows to the conflict in Chad

- ↑ Chad troops return from Mali

- ↑ Mali’s neighbors take steps to keep al Qaida militants from escaping

- 1 2 Ogorkiewicz, R. M. AFV Weapons Profile 039 Panhard Armoured Cars (Windsor, Berks: Profile Publications).

- ↑ "South Africa's impressive history in the design and manufacture of armoured vehicles". South African Engineering News. 2014-10-08. Retrieved 2014-07-18.

- ↑ Virleo Test Report

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ratel

- ↑ Fact File: The Ratel infantry combat vehicle

- ↑ Adrian English. Irish Army Orders of Battle 1923-2004 (2005 ed.). Tiger Lily Books. p. 78. ISBN 978-0972029674.

- ↑ Jane's International Defense Review, 2004, Volume 37 #7-12 p. 1.

- ↑ Chant, Christopher. A Compendium of Armaments and Military Hardware (1987 ed.). Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd. p. 32. ISBN 0-7102-0720-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Corbadus Issue 25 Volume 2

- 1 2 L'AUTOMITRAILLEUSE LEGERE PANHARD

- ↑ Greybe, David (30 March 2000). "South Africa: SANDF Finds Its Stolen' Cannons". Business Day. Rosebank, Johannesburg. Archived from the original on November 13, 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- 1 2 Gander & Charles Cutshaw, Terry. Jane's Ammunition Handbook 2000-2001 (2000 ed.). Jane's Information Group. pp. 18–685. ISBN 978-0710620125.

- ↑ "M. J. LE ROUX, ARMOUR, 1978-1979". Sentinel Projects. 2003-11-19. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ↑ SA Now. South African Communication Service, 1996, Volume 1 p. 24.

- ↑ Africa Research Bulletin, 1998, Volume 35 p. 13022. Africa Research Bureau, Ltd.

- ↑ Weapon Systems - Annual Report, South African Department of Defence. Public copy: 1997.

- ↑ "SANDF gets rid of surplus". South African Associated Press. 2005-10-04. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- ↑ "Tender Announcements". Armscor South Africa. 2009-11-16. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- ↑ "Museum's army vehicles seized". South African Associated Press. 2005-10-04. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- ↑ "Experts up in arms over SANDF weapons records". IOL.co.za. 2005-01-21. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- ↑ "Confiscated museum tanks may have been used before seizure". MSN South Africa. 2005-11-03. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- ↑ "All four confiscated vehicles now back at SA military museum". DefenceWeb. 2016-02-29. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- ↑ Meyer, Marinda (2010-12-13). "Farewell to One of Armour's Pillar of Support, 30 July 2010, Bloemfontein". South African Department of Defence. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ Ramkissoon-Pillay, Deshni (2013-10-24). "UMR plans to restore military vehicles". The Highway Mail. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ Joubert, Werner (2014). "Potchefstroom military proves to be a community asset" (PDF). South African Soldier Magazine. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 7, 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ Lord, Regine (2013). "Regiment Oranjerivier celebrates its 60th Birthday with the opening of the new ROR Laager at Fort Ikapa" (PDF). The Reserve Force Volunteer. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 13, 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ Letaoana, Lebohang (October 2006). "Sixty years of sound harmony between man and machine" (PDF). South African Soldier Magazine. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 13, 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ Snyman, T.N. (June 2004). "A New Lion in the Pride" (PDF). South African Soldier Magazine. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 24, 2010. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ Van den Berg, B.J. (July 2005). "Our Army Bids Our Chief Farewell" (PDF). South African Soldier Magazine. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2010. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ "Retired firepower: The Littlefield Collection auction". 2014-03-03. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- ↑ "United Nations Register of Conventional Arms: Report of the Secretary-General" (PDF). New York: United Nations. 14 July 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ Midlands Zimbabwe Military Museum, Zim Field Guide, 2016, archived from the original on November 13, 2016, retrieved 2016-11-13

- ↑ Montesi, Stephano ([date unspecified]). "Sahara Occidentale, Museo dell'Esercito di Liberazione Popolares". Buena Vista: Common Archive of Italian Photographers. Archived from the original on November 13, 2016. Retrieved 2016-11-12. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Liebenberg, John (27 November 1987). "Angola invasions: Many more have to die" (PDF). The Namibian. Windhoek. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 13, 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ Museu Nacional de historica militar - Angola, Operacional (Grupo Militar), 2013-07-12, archived from the original on October 13, 2015, retrieved 2016-11-13

- ↑ DIO blindé au Bénin

- ↑ Senegal Instruction Operationelle Au Profit Des Forces Armees Beninoises

- ↑ Republique du Benin

- ↑ "Papers and death merchants". Africa Confidential. 2008-02-15. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ↑ "Tentatives de déstabilisation de la Côte d'Ivoire : Des assaillants attaquent la position des Frci à Grabo". Lepointsur.com. 2015-01-12. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-28.

- ↑ "CÔTE-D'IVOIRE:LA GENDARMERIE DE GRABO ATTAQUÉE, DEUX MORTS AU RANG DES FRCI". lecridabidjan.net. 2015-01-10. Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-28.

- ↑ Cordesman, Anthony H. A Tragedy of Arms: Military and Security Developments in the Maghreb (November 30, 2001 ed.). Praeger Publishers. p. 62. ISBN 0-275-96936-3.

- ↑ South West African Territorial Forces SWATF in 'Südwestafrika/Namibia Heute'

- ↑ Heitman, Helmoed-Römer. Modern African Wars: South-West Africa (1991 ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-1855321229.

- ↑ Units - The South West Africa Territory Force

- ↑ Locke & Cooke, Fighting Vehicles and Weapons of Rhodesia (1995), p. 100.

- ↑ Treyarch (2012-11-30). Call of Duty: Black Ops II. Xbox 360. Activision. Level/area: Pyrrhic Victory.

- ↑ Bond, Larry. Vortex (1991 ed.). Warner Books, Inc. p. 59. ISBN 978-0446363044.

- ↑ Kratman, Tom. The Liberators (2011 ed.). Baen Books. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-4391-3402-3.

External links

|

|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eland Mk7. |

- Photo gallery at Primeportal.net

- Photo gallery at SA Transport

- "Rhodesian Armoured Cars", July 2011 - South African Military History Society

- Selected short stories from Billy: Reminiscences of an Eland-90 commander

- Sentinel Projects: Personal accounts of military service in the SADF and Border War

- Eland (Armoured) Noddy Car

- 61 Mechanised Battalion Group Veterans' Association