Rail transport in Puerto Rico

- This article is part of the history of rail transport by country series.

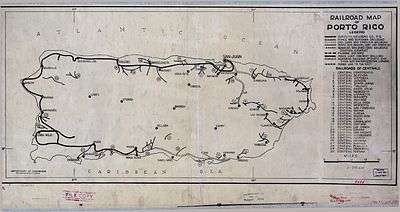

Rail transport in Puerto Rico currently consists of a 10.7-mile (17.2 km) passenger metro system in the island's metropolitan area of San Juan. Its history can be traced back to the mid-19th century with the construction of a limited passenger line in Mayagüez. Between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Puerto Rico's rail transport system expanded significantly, becoming one of the largest rail systems in the Caribbean at the time thanks to an economic boom in agriculture industries, especially the sugar cane industry. The rail system was expanded to include passenger travel with a direct line from the island's northern capital of San Juan to the western and southern cities and towns, greatly improving travel and communication within the island. However, the entire system was soon overshadowed by the arrival of the automobile, and by the 1950s was completely abandoned. Small remnants of this system still exist in some parts of Puerto Rico, some conserved for tourism purposes.

History

Early Mayagüez passenger system

Although Puerto Rico did not have a national railroad system until the last decade of the 19th, between the 1870s and 1890s, the city of Mayagüez did have a small passenger rail system for transporting its residents, mainly along the current Mendez Vigo Avenue.[1] It was originally proposed by Jose A. Gonzalez y Echevarría in 1870 under the company El Ferrocarril Urbano de la Villa de Mayagüez (the Urban Train of Mayagüez),[2] with the line being built between 1872 and 1875. The simple street railway system consisted of small wagons on rails pulled by horses, and connected the center part of the town with the Playa sector (now Port sector). It faced numerous difficulties, including inclined routes and poor street conditions, which were troublesome for the animals. The system stopped in 1887 after the company was unable to obtain certain permits, but was revived in 1893 after a proposal by the company Sociedad Anónima Tranvia de Mayagüez (the Mayagüez Tramways Anonymous Society) and renewed operations in 1895.[2]

The new system operated more efficiently, offering more comfortable cars and more stops, including one in the town Market Place (Plaza del Mercado) and another in the Guanajibo neighborhood. The routes were altered to pass through McKinley Street, which was less inclined and with better road conditions than previous routes benefiting both the ride and the horses. It lasted until 1912, when the Mayagüez Tramways Anonymous Society ceased operations and was replaced by the Mayagüez Tramway Company in 1913.[2] The third operator of the system introduced new larger electric-powered cars, although the service was now limited from the Playa sector directly to the Balboa neighborhood. It remained active for 13 years, but after a major earthquake hit Mayagüez in 1918, coupled with the recent arrival of the automobile, it was shut down permanently in 1926.[2]

San Juan Tramway

In 1878, engineer-entrepreneur Don Pablo Ubarri was granted a permit to build and operate a 7-mile (11.3 km) passenger steam tramway between San Juan and the town of Río Piedras.[3] This interurban system was the beginning of colonization of the hinterland of the walled city of San Juan.[3] In 1901, the San Juan Light & Transit Co. replaced the steam tram by a new electric tram system.[4] The stops or paradas along the avenue were numbered, from 1 in Old San Juan to 40 in Río Piedras. The numbers became so identified with the locations that some street maps still show them today. In 1911 a new line going through Condado in Santurce is constructed by the Porto Rico Railway, Light & Power Co.[5] Locally referred to as the Trolley de San Juan, or San Juan Trolley in English, it crossed the streets of San Juan from 1901 to October 1, 1946. During its heyday, it was the most modern electric tramway system in Puerto Rico, rivaling New York and Toronto, the cars had such features as steel arch roof bodies, improved ventilation, up to 65 seated passengers capacity and air operated front and centre doors, with more than 14.5 miles (23.3 km) of tracks and 36 passengers coaches, it transported nearly 10 million passengers a year. A stroll cost ten cents.[6]

The event of World War II, the creation of the San Juan-Santurce Omnibus Line, the White Star Bus Line and the San Felipe (1928) and San Ciprián cyclones in 1932 caused serious damages to this transit system.[7]

National railroad system

The main Puerto Rico rail system was created during the late 19th century and was significantly expanded during the early 20th century due to a growing sugar cane industry in the island.[8] Its origins can be traced back to 1874, when a Spanish engineer proposed building a steam railroad line along the coast of Puerto Rico. The study for this project served as a base for the definitive construction, which began in 1888. It would take almost 20 years to complete the whole route from San Juan to Ponce.[9] The main system began operations in 1891, when the northern line was built between San Juan (in the Martín Peña sector) and the town of Manatí, followed by extensions to the towns of Carolina (to the east) and Arecibo/Camuy (to the west) the following year. When the United States invaded Puerto Rico in 1898, the system already had approximately 168 mi (270 km) of railroad tracks.

Passenger travel began to flourish in 1902 when the American Railroad Company from New York acquired the system.[10] In 1904, a southern line was constructed between Hormigueros and Yauco. The northern line was expanded towards the west of San Juan to include the towns of Arecibo and Aguadilla. One of the most significant projects of this line was linking the main rail line through Quebradillas and Isabela, requiring the construction of tunnels and tall bridges, including the Guajataca Tunnel completed in 1904.[11] In 1907, the northern line of San Juan was connected to the southern line of Ponce, finally connecting the northern and southern portions of the island.

Before its demise, the Puerto Rico railroad system had some 500 kilometers (310 miles) of track and served almost all coastal towns, carrying freight into the Island and transporting agricultural products to the ports for shipping overseas.[6] The construction of the national railroad system produced tunnels and bridges which were noted for their architecture and local importance.[11][12] The Puente Blanco, completed in 1922, and the Caño San Antonio rail bridge completed in 1932,[12] were designated as Historical Places by the U.S. National Park Service in 1984 and 2009, respectively,[13][14] while the Guajataca Tunnel was designated as a Historical Monument by the Puerto Rico Legislature in 2000.[11] Many of these structures were designed and built under the supervision of Etienne Totti,[12] who was at the time the head engineer of the American Railroad of Porto Rico and would become the first president of the Puerto Rico Professional College of Engineers.

Transport by rail greatly improved the everyday life of Puerto Ricans, since passengers could now travel between the largest cities, San Juan and Ponce, in record time. Previous trips used to take several days by horse and wagons, but the regular train greatly reduced traveling time to around 10 hours. There were four main trains operating all day and night during the system’s peak years, with Train No. 1 departing at 7:00am from San Juan and arriving in Ponce at 5:00pm. Tickets for this one-way trip cost $1.50 for first class and $0.95 for second class in 1950.[10] The system was such an important part of island society, that famed composer Manuel “Canario” Jimenez composed a Plena song titled La Máquina (The Machine) about the daily trip between San Juan and Ponce.

Tragedy on election day in 1944

On the early morning hours of November 7, 1944, the American Railroad Company of Puerto Rico suffered the most violent accident in its history.[15] Train No. 3 was traveling from San Juan to Ponce carrying passengers to their different hometowns for the island general elections to be held that same day. It stopped at the Jimenez Station in Aguadilla for a routine engineer and fireman exchange with Train No. 4 which was heading towards San Juan. The engineer assigned to Train No. 3's ride from Jimenez Station to Ponce was Jose Antonio Roman, an experienced freight train engineer, but who had never worked in passenger travel.[15] When the train left the station at 2:00am, it was hauling 6 passenger cars with hundreds of commuters and two freight cars.

At 2:20am the train started to descend a hill section known as Cuesta Vieja (Old Hill) in Aguadilla at what some witnesses described as an exaggerated speed. When the train reached the leveling-off point at the bottom of the hill it derailed. The steam locomotive crashed into a ditch and one of the freight cars crashed into one of the passenger cars, killing many inside. Witnesses described the scene as horrendous, with some accounts stating that parents were throwing their children out the windows to save them from the wreckage.[15] Chief of Police Guillermo Arroyo stated that the locomotive (No. 72), the express car, and three second class passenger cars were completely destroyed. Oscar Valle, an Aguadilla correspondent to the local El Mundo newspaper, summarized the scene in a more dramatic way: "The locomotive suffered a terrible explosion as it derailed, and the impact was so strong that 3 passenger cars were converted into a fantastic mound of wreckage."[15] In the end, 16 passengers lost their lives, including the engineer and the fireman, and 50 were injured in the crash.

Downfall

The former San Juan railroad terminal.

The former San Juan railroad terminal.- Abandoned Central Mercedita Plymouth DE 50-ton locomotive in the Mercedita Serralles Refinery near Ponce.

- Old train bridge in the San Juan district of Santurce, near San Juan Central Park.

Exposed rails at the Old San Juan Port, facing the old "Calle del Tren" (Train Street; today an exclusive bus street).

Exposed rails at the Old San Juan Port, facing the old "Calle del Tren" (Train Street; today an exclusive bus street).

When Puerto Rico changed its mostly agricultural economy to a manufacturing one, and the U.S. and Puerto Rican governments started investing heavily in interstate highways and freeways, the railroad business in the island soon collapsed. The system was almost lost when the American Railroad Company filed for bankruptcy in 1947.[10] In an effort to save the system, former employees reorganized the company and formed the Puerto Rico Railroad and Transport Company serving as stockholders,[10] but by then the system could no longer compete with the increasing number of automobiles, trucks, and buses on the island. Passenger travel ceased in 1953, while the commercial service (mostly for the sugar cane industry) continued operating until 1957. Small portions of the system remained operational for local industries, including the Mercedita and Arroyo sugar refineries, until the collapse of the sugar cane industry in the early 1990s.

The last remaining part of the system used in operations was a small rail line located in the town of Arroyo, which was used exclusively for tourism purposes until recently.[16][17] The rest of the system was either torn down to make room for new development, recycled (rails were melted and recycled and certain rail bridges were converted into road bridges), or simply abandoned. Remnants of the main system and lines can still be seen in some parts of Puerto Rico, such as:

- The Caño San Antonio rail bridge

- Tracks, in the streets of the Playa de Ponce neighborhood of Ponce;

- Tracks, along the old port section of Mayagüez;

- Bridge in Aguadilla over Culebrinas River near Central Coloso behind PR-111 junction with PR-418

- Abandoned diesel locomotives and sugar cane wagons, in the Serralles Distillery (home of the Don Q liquor), next to Mercedita Airport, in Ponce;

- Tracks and bridges, along PR-1 state road in the southern region of the island;

- Tracks, bridges and abandoned sugar cane wagons, in the Aguirre neighborhood between the Salinas, Arroyo and Guayama towns;

- Steam locomotive (1,000 mm/3 ft 3 3⁄8 in metre gauge CAIL n° 2296 2-6-0T, French built year 1889 steam locomotive, FCPR n°2 - in duty in France at Chemin de Fer de la Baie de Somme after being presented to Henri FORD in 1929 by ARR PR and sent back from Michigan to France in 1994;

- Steam locomotive (1,000 mm/3 ft 3 3⁄8 in metre gauge Baldwin #53959 0-4-2 steam locomotive - Hacienda Dolores #2), on display in a public plaza in Peñuelas;

- Steam locomotive (2 ft 6 in/762 mm gauge Baldwin #60180 2-8-0 Consolidation steam locomotive - Central Pasto Viejo [incorrectly painted as Central Constancia] #7), on display in a public park in Levittown;

- Steam locomotives, abandoned and rusting in the Vieques wilderness;

- Tunnel, between the Guajataca and Pastillo beaches, near the Guajataca Forest Reserve in Quebradillas;

- Tunnel, hidden in the Guajataca Canyon;

- Tunnel, in Guaniquilla section of Cabo Rojo;

- Bridge, in the Santurce neighborhood of San Juan, close to San Juan Central Park.

- Exposed tracks (of the otherwise asphalt covered tracks) in front of the Cargo Ship Docks in Old San Juan.

- Three bridges inside Fort Buchanan, exposed rail.

- Puente Blanco bridge in Quebradillas.

- Exposed tracks, in Caguas. Road #1 lane going from Rio Piedras to Caguas, near Bairoa

- Former railroad stations in Aguada, Añasco, Hormigueros, Barceloneta, Cabo Rojo, San Germán, Manati and Vega Baja.

- Tracks, by the south side of Central Coloso, in Aguada.

Tren Urbano

.jpg)

The Tren Urbano is a heavy-rail commuter metro system serving the cities of Bayamón, Guaynabo and San Juan. It is the only active rail system serving the general public in Puerto Rico, with 16 stations along a 10.7-mile (17.2 km) route. It is electrified by third rail at 750 V, d.c.. The line's construction started in July 1996 with the purpose of relieving traffic congestion in the San Juan metropolitan area, and was inaugurated January 2005 to mixed reactions. With a final estimated cost of $2.25 billion, nearly $1 billion more than original estimates,[18] the project has been criticized by government watchdogs, especially for its low passenger use of approximately 24,000 daily passengers (2005 est.), compared with original projections of 80,000.[18]

Upon its inaugural opening, there were initial plans to extend the Tren Urbano rail system to outlying suburbs of the San Juan metro area, including a light interurban rail system from San Juan to Caguas originally scheduled to be completed in 2010,[19] however these designs have not been finalized and no construction work has commenced yet. The proposed Caguas rail project remains postponed as of July 2009.

Other systems

Chemex Railroad

The Chemex Railroad (a.k.a. Port of Ponce Railroad) was a short, 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) industrial railroad located in the southern city of Ponce and was the last remaining operational freight railroad on the entire island until it ceased operations sometime in 2010.[20] It first began operations in 1988 under the control of CHEMEX Corporation's predecessor PharmaChem, a supplier of chemicals to Puerto Rico’s pharmaceutical industry, which primarily used the railroad to ship inbound chemical products via a railroad ferry connection from Mobile, Alabama in the U.S. mainland to the marine terminal within the Puerto de Las Américas.[21]

The entire rail system consisted of an eight-track railroad yard, a railroad ferry terminal, and two diesel switcher locomotives.[22] The two engines, an EMD SW1 and EMD SW9, made up the primary locomotive roster to assist in most of its switching activities and the loading of rail cars onto barges.[23] About twice each month from the Port of Mobile, the railroad ferry service transported an average of 24 tank cars throughout each voyage, delivering and receiving both loaded and unloaded cars from the terminal to the rest of the national U.S. rail network.[20][21]

Train of the South

The Train of the South was an historic, 3 ft (914 mm) narrow gauge plantation line dedicated exclusively for tourism in Arroyo. Several passenger wagons pulled by a Plymouth WDT 40-ton diesel locomotive transported visitors on an hour-long guided tour along old sugar cane fields. This line has been temporarily closed in 2005,[16][17] but there are petitions to revive and extend the system.[24]

El Parque del Tren

El Parque del Tren was a little train within a park dedicated exclusively for park attendees. It was also the last remaining rail line open to the general public until the inauguration of the Tren Urbano. It consisted of a locomotive with various passenger cars which would carry visitors around a large recreational park in Bayamón. As part of its construction, the park was demolished to make way for the Tren Urbano.[25]

See also

- Defunct systems

- List of Puerto Rico railroads

- List of United States railroads

- Rail transport in the United States

- Transportation in Puerto Rico

References

- ↑ Puerto Rico: Society and Culture Before the US Invasion of 1898: Transportation Institute of Puerto Rican Arts and Culture (IPRAC) (Spanish)

- 1 2 3 4 The Mayagüez Trans-Way, First Urban Rail System of Puerto Rico (El Tranvía de Mayagüez, Primer Ferrocarril Urbano de Puerto Rico), New Mayagüez Foundation, Inc. (Fundación Nuevo Mayagüez, Inc.) (Spanish)

- 1 2 (Spanish) San Juan: Historia Illustrada de su desarrollo urbano, 1508-1898 - Aníbal Sepúlveda Rivera. San Juan 1989, pp. 209-211. Centro de Investigaciones CARIMAR.

- ↑ Document CF408, Tranvía de la Capital a Río Piedras (Nov 16, 1898), Archivo General de Puerto Rico

- ↑ Canadian Transit Interests Outside Canada

- 1 2 An Island Grows, 70 Years of Economic Development in Puerto Rico, 1877 - 1947 (1947) Biblioteca UPR.

- ↑ Historia de la energía eléctrica en Puerto Rico - Eugenio Látimer Torres

- ↑ Pumarada O'Neill, L. (1980). Trasfondo histórico del ferrocarril en Puerto Rico. Mayagüez: Centro de Investigaciones de Ingeniería, Recinto Universitario de Mayagüez, págs. 5-7. (Spanish)

- ↑ Pumarada O'Neill, L. (1980). Trasfondo histórico del ferrocarril en Puerto Rico. Mayagüez: Centro de Investigaciones de Ingeniería, Recinto Universitario de Mayagüez, págs. 8-9, 25. (Spanish)

- 1 2 3 4 Violeta Landron, The Train: Memories and Nostalgia on Rails (El Tren: Recuerdos y Nostalgia sobre Rieles), Fiestas Patronales 2000, Vega Baja, PR, Pg. 44 (Spanish)

- 1 2 3 "Puerto Rico Public Law 340 of 2000". State Legislature of Puerto Rico. September 2, 2000. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Bermejo, Nelson (March 3, 2014). "De vuelta por el puente ferroviario del caño San Antonio". blog. Metro.pr. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Nomination Document. NRHP" (PDF). National Park Service. 1984. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- ↑ "Nomination Document. NRHP" (PDF). National Park Service. 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 La Tragedia del 7 de noviembre de 1944 (The Tragedy of November 7, 1944) by Haydee E. Reichard de Cancio, El Nuevo Dia, Por Dentro Section, Pg. 116, December 7, 1996, retrieved on July 31, 2006 (Spanish)

- 1 2 TravelandSports.com, Tren del Sur de Arroyo

- 1 2 PRFROGUI.com El Tren del Sur (Arroyo)

- 1 2 Tren Urbano PR another way low transit ridership forecast, TOLLROADSNews, November 20, 2005, accessed April 13, 2007.

- ↑ "Caguas To San Juan In 15 Minutes". Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- 1 2 Railroads of Puerto Rico: Ferrocarril Chemex Brief information and photographs of the Chemex Railroad operation in Ponce.

- 1 2 American Shipper Article: Where the Rail Meets the Water

- ↑ Google Maps – Ponce, PR Observations from a Google Maps satellite image with a view of the Port of Ponce (Chemex) railroad yard.

- ↑ Reed, Jay (2002). Comprehensive Guide To Industrial Locomotives (3rd ed.). Rio Hondo. ISBN 0-9647221-3-5.

- ↑ Government of Puerto Rico State Historic Conservation Plan 2006-2010 (Spanish)

- ↑ Baymon Tourism, RadioSabor.es

Further reading

- Jack Delano (June 1990), De San Juan a Ponce En El Tren (From San Juan to Ponce in Train), University of Puerto Rico, ISBN 0-8477-2117-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rail transport in Puerto Rico. |

- The Ponce Railroad station on Calle Ferrocarril, Ponce, circa 1900s Accessed January 5, 2011.

- Railroads of Puerto Rico – A site dedicated to the history of railroading in Puerto Rico.

- Tren Urbano Home Page (Spanish)

- The Tramways of San Juan (English)

- Puerto Rico Public Art Project – Tren Urbano – Photos and information related to the artwork located on each of the train route's stations. (Spanish)

- Ponce, PR railroads

- Ponce, PR trains