The Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia (1699-1841) was a medical guide for physicians and apothecaries which provided standardised recipes and methods of producing remedies which could be consulted by practitioners when prescribing treatment. It was first published by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh in 1699. In 1864 the Pharmacopoeia merged with the London and Dublin Pharmacopoeia's to create the British Pharmacopoeia.

History

The College Pharmacopoeia, 1699

The first Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia was issued to meet the need that developed as the apothecary ‘confined himself to the preparation and composition of medicines which the physician prescribed.’[1]

Sir Robert Sibbald and Andrew Balfour were important figures in the creation of the Scottish Pharmacopoeia and initially began work in 1680. The first item in the first minute of the RCPE in 1682 relates to the creation of a committee for the Pharmacopoeia.[2]

The Physicians wanted to separate the two branches of medicine, between physicians and surgeons, and wanted to regulate the practice of pharmacy themselves. The College of Physicians claimed supervisory and licensing powers over the apothecary in Edinburgh through its Charter and through an Act of Parliament and tried diligently to implement them. However the first edition makes no reference to this struggle, later editions all explicitly refer to them in their prefaces.[1]

Sir Archibald Stevenson was appointed chairman of the committee for the creation of the Pharmacopoeia and under his five years of leadership a series of committees struggled to agree upon a text for publication.

Finally, in 1699, nineteen years after work on the Pharmacopoeia began, a text was agreed upon and published, titled Pharmacopoea Collegii Regii Medicorum Edimburgensium.[1]

Arrangement

The early editions were arranged in three parts. First there was a list of ‘Simples’ about 50 pages, subdivided into vegetable, animal, and mineral sources. This was followed by 150 pages of preparations, subdivided into categories such as tinctures, powders and electuaries. Lastly were about 50 pages of chemical medicines, subdivided into those made of animal, vegetable and mineral sources. This was the basic organisation through to the fifth edition (1756). In the 6th edition (1774) ‘Simples’ gave way to ‘Materia Medica’ and the old subdivisions were discarded. The second and third parts were merged into one section called ‘Preparations and Compositions.’[1]

Developments in arrangements were made under the direct influence of Sir John Pringle, who was then approaching the height of his eminence in London and one-time member of the Pharmacopoeia Committee of the Edinburgh College. At the request of the College's President (John Boswell), Pringle set forth his views on the revision of the Pharmacopoeia in a string of letters. Pringle recommended a completely alphabetised arrangement of the Pharmacopoeia.[1]

The first edition was ‘according to the notions of the time… overloaded with a variety of useless and disgusting substances.’ The perseverance of inelegant materia in a time of growing reason and science indicated the tenacity of folk medicine and the power of authority and tradition. It was not until the fifth edition (1756) that the beginnings of rational cleansing of content becomes evident. [1]

Eliminations were not all made by subjecting the old superstitions and credulities to either reason or ridicule. Some were made for very practical reasons. For example, only the substances still in use were included, preparations were not included which could not keep on the apothecary’s shelves, some were excluded so as to not restrict the freedom of choice of physicians, and many remedies were common in the household and were superfluous in an official compendium. Addition of new medicines, which shows the influence of the developments in chemistry. The College contended that new drugs were accepted into the Pharmacopoeia only by virtue of the experience of the College itself or by the recommendations of noted men. This meant that the materia medica was beginning to take on the scientific aura of pharmacological study and clinical test.[1]

Revision

The Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia, 1699-1841

Unlike the London Pharmacopoeia, the Edinburgh College frequently revised its Pharmacopoeia. In the 142 years from the first edition to the last there were twelve published editions. Critics of revision thought this made the Pharmacopoeia unreliable in its principles. Others, however, felt that frequent revision would keep it in line with the progress of science and that the changes would keep pharmacy dynamic. Each revision received careful consideration and often the results were circulated among the College. The College was keenly aware of its professional obligations and its responsibility to the public. In 1839, the College issued an edition in English, owing to the popularity of earlier editions translated into English and the ‘slow sale of the last Latin edition.’[1]

Developments in terminology and the language used in the Pharmacopoeia were reflective of scientific developments. Proponents of new terminology contended that uniformity and universality was rational, would end confusion and aid progress in pharmacy.[1]

The Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia was one of the most influential works of its kind while it was in circulation. It went through no less than 20 printings. There were at least 12 printings in Latin throughout Europe and translations appeared in Dutch and German. The Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia played a direct role in influencing the creation of the American Pharmacopoeias.[1]

By 1817 the RCPE had made nine significant revisions and published its last (10th) edition in Latin. In 1839 and 1841 it published two editions of the Pharmacopoeia in English, under the title The Pharmacopoeia of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. After this, the Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia was combined with the London and Dublin Pharmacopoeia’s to create the British Pharmacopoeia, which was first issued in 1864.[1]

Editions

- First - 1699

- Second - 1722

- Third - 1735

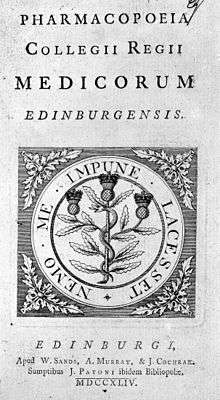

- Fourth - 1744

- Fifth - 1756

- Sixth - 1774

- Seventh - 1783

- Eighth - 1792

- Ninth - 1803

- Revised Ninth - 1805

- Tenth - 1817

- Eleventh (First in English) - 1839

- Twelfth (Second in English) - 1841

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cohen, David (1957). "The Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia". Medical History. 1: 123–134.

- ↑ Craig, W.S. (1976). History of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. Blackwell Scientific Productions. p. 93.