Central Zone (Hindi)

| Hindi (Central Zone) | |

|---|---|

| Madhya | |

| Geographic distribution: | South Asia |

| Linguistic classification: |

|

| Subdivisions: |

|

| Glottolog: |

None west2812 (Western Hindi)[1] east2726 (Eastern Hindi)[2] |

| |

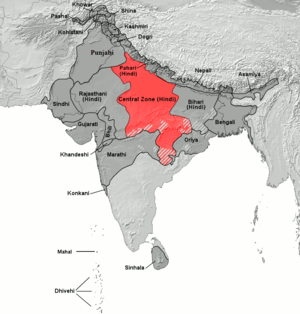

The Central Zone or Madhya are the central varieties of the Hindi Belt of the Indo-Aryan languages. It is a dialect continuum in the Hindi zone spoken across northern India that descend from the Madhya Prakrits. The Western Hindi languages include Hindustani, of which the official languages of India and Pakistan, Modern Standard Hindi and Urdu, are mutually intelligible standardizations of the Khariboli dialect, the prestige dialect of Hindustani. The coherence of this group depends on the classification being used; here only Eastern and Western Hindi will be considered.

Languages

If there can be considered a consensus within the dialectology of Hindi proper, it is that it can be split into two sets of dialects: Western and Eastern Hindi.[3] Western Hindi evolved from the Apabhramsa form of Shauraseni Prakrit, Eastern Hindi from Ardhamagadhi.[4]

The Eastern Hindi languages are not shown individually. They are Awadhi in the north, east of Hindustani and Kannauji; Bagheli in the center, to the east of Bundeli, and Chhattisgarhi to the southeast of Bundeli.

- Western Hindi[5]

- Braj Bhasha (Brajbhakha), spoken in western Uttar Pradesh and adjacent districts of Rajasthan and Haryana

- Haryanvi (Bangaru), spoken in the states of Haryana and Delhi.

- Bundeli, spoken in south-western Uttar Pradesh and west-central Madhya Pradesh.

- Kannauji, spoken in west-central Uttar Pradesh.

- Hindustani, including the standard vernacular dialect Khariboli (and its standardised forms Standard Hindi and Urdu), spoken in western Uttar Pradesh and Delhi.

- Eastern Hindi

- Awadhi, spoken in north and north-central Uttar Pradesh.

- Bagheli, spoken in north-central Madhya Pradesh and south-eastern Uttar Pradesh.

- Chhattisgarhi, spoken in southeast Madhya Pradesh and northern and central Chhattisgarh.

- Bhojpuri, spoken in eastern Uttar Pradesh, western Bihar, northwestern Jharkhand, the northeastern part of Madhya Pradesh, and in the northern part of Chhatisgarh, it is also spoken in Madhesh, Nepal. It is also spoken by the Bhojpuri diaspora in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname, Jamaica, other parts of the Caribbean, Fiji, Mauritius, and South Africa.

Romani, Domari, Lomavren, and Seb Seliyer (or at least their ancestors) appear to be Central Zone languages that migrated to the Middle East and Europe ca. 500–1000 CE in three distinct waves. Parya is a Central Zone language of Central Asia.

To Western Hindi Ethnologue adds Sansi, Powari, Chamari (a spurious language), Bhaya, Gowli (not a separate language), and Ghera.

This analysis excludes varieties sometimes claimed for Hindi for cultural reasons, such as Bihari, Rajasthani, and Pahari.[6]

Use in culturally non-Hindi regions

- Urdu is the official language of Pakistan. Although only the native language of 7% of the population, it is nearly universal as a second language among the literate.

- Bombay Hindi ("Bombay Bat"), the dialect of the city of Mumbai (Bombay); it is based on Hindustani but heavily influenced by Marathi. Technically it is a pidgin, i.e. neither is it a native language of any people nor is it used in formal settings by the educated and upper social strata. However, it is often used in the movies of Hindi cinema (Bollywood) because Mumbai is the base of the Bollywood film industry.

- Dakhini, including Hyderabadi Urdu, and Bangalori Urdu, a dialect of Urdu spoken in the present areas of the erstwhile Hyderabad State, and the historical Deccan region. There is a small but distinct difference between Dakhini and standard Hindi-Urdu, which is bigger the further south it is spoken.

- Kolkata Hindi, a Khariboli-based pidgin spoken in the city of Calcutta (Kolkata), Shillong, etc.; heavily influenced by Bhojpuri and Bengali.

- Andaman Creole Hindi is a trade language of the Andaman Islands.

- Fiji Hindi is an Eastern Hindi lingua-franca that developed among Indo-Fijians.

- Caribbean Hindustani is a Eastern Hindi lingua-franca that developed among Indo-Caribbeans, it is very similar to the Bhojpuri dialect of Hindi and to Fiji Hindi.

Comparison

The standard educated Delhi Hindustani pronunciations [ɛː, ɔː] commonly have diphthongal realizations, ranging from [əɪ] to [ɑɪ] and from [əu] to [ɑu], respectively, in Eastern Hindi varieties and many non-standard Western varieties.[7] There are also vowel clusters /əiː/ and /əuː/.

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Western Hindi". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Eastern Hindi". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ (Shapiro 2003, p. 251)

- ↑ (Shapiro 2003, p. 277)

- ↑ Grierson, George A. (1916). "Western Hindi" (PDF). Linguistic Survey of India. Volume IX: Indo-Aryan family. Central group, Part 1, Specimens of western Hindi and Pañjābī. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, India.

- ↑ (Shapiro 2003, pp. 251–252)

- ↑ Shapiro, Michael C. (2003), "Hindi", in Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh, The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, p. 258, ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5

Bibliography

- Shapiro, Michael C. (2003), "Hindi", in Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh, The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, pp. 250–285, ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5