Early life of Robert E. Howard

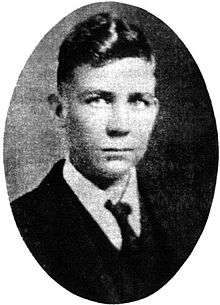

Robert Ervin Howard (January 22, 1906 – June 11, 1936) was an American author born in Peaster, Texas but who traveled between many different towns across Texas until he was thirteen, when his parents settled in the town of Cross Plains, Texas.

Childhood

Howard was born January 22, 1906 in Peaster, Texas, the only son of a traveling country physician, Dr. Isaac Mordecai Howard, and his wife, Hester Jane Ervin Howard.[1][2][nb 1][nb 2][nb 3] Both sides of the family had roots throughout the American South, with various ancestors owning plantations and fighting for the Confederacy in the Civil War.[3]

Traveling

The author's early life was spent wandering through a variety of Texas cowtowns and boomtowns: Dark Valley (1906), Seminole (1908), Bronte (1909), Poteet (1910), Oran (1912), Wichita Falls (1913), Bagwell (1913), Cross Cut (1915), and Burkett (1917).[1][4][5]

The Howards arrived in Bagwell in early 1913 and Dr. Howard was granted a licence to practice medicine there on April 30, 1913.[6] Howard scholar Patrice Louinet wrote that the Howard family may have arrived in the town for Dr. Howard to take over from Dr. Willis Walter Stephens.[6] It was in Bagwell that Robert E. Howard first went to school. The school in Bagwell only began when a child was eight, so Howard entered it in 1914.[6] However, he was not to attend this school for long as the family left for Cross Cut in January 1915.[7]

Other themes began to appear at this time which would later seep into his prose. Although he loved reading and learning, he found school to be confining and began to hate having anyone in authority over him.[8][9] Experiences watching and confronting bullies revealed the omnipresence of evil and enemies in the world, and taught him the value of physical strength and violence.[10] Being the son of the local doctor gave Howard frequent exposure to the effects of injury and violence, due to accidents on farms and oil fields combined with the massive increase in crime that came with the oil boom.[11] Firsthand tales of gunfights, lynchings, feuds, and Indian raids developed his distinctly Texan, hardboiled outlook on the world.[12]

Sports, especially boxing, became a passionate preoccupation.[13] At the time, boxing was the most popular sport in the country, with a cultural influence far in excess of what it is today. James J. Jeffries, Jack Johnson, Bob Fitzsimmons, and later Jack Dempsey were the names that inspired during those years, and he grew up a lover of all contests of violent, masculine struggle. Specifically, he focused in on a type of boxer called Iron Men at the time, tough battlers who had little skill but made up for it in the sheer ability to take punishment that would kill a lesser man. Inspired by these heroes, Howard lifted weights, practiced boxing and wrestling with friends, and read everything he could find on the subject—most notably in magazines such as The Ring and Police Gazette.

Voracious reading, along with a natural talent for prose writing and the encouragement of teachers, created in Howard an interest in becoming a professional writer.[14][15] From the age of nine he began writing stories, mostly tales of historical fiction centering on Vikings, Arabs, battles, and bloodshed.[16][17] One by one he discovered the authors that would influence his later work: Jack London and his stories of reincarnation and past lives, most notably The Star Rover (1915); Rudyard Kipling's tales of subcontinent adventure and his chanting, shamanic verse; the classic mythological tales collected by Thomas Bulfinch. Howard was considered by friends to be eidetic, and astounded them with his ability to memorize lengthy reams of poetry with ease after one or two readings.[14][18][19] Elsie Burns, who was Howard's neighbor and the postmistress of Burkett, recalled an encounter with Howard and his dog Patch in 1915. As she recalled the event, he told her, "I'm Robert Howard, I'm sorry if we frightened you. Patches and I are out for a morning stroll. We like to come here where there are big rocks and caves so we can play make-believe. Some day I am going to be an author and write stories about pirates and maybe cannibals. Would you like to read them?"[17][20]

Teens

Cross Plains

In 1919, when Howard was thirteen, Dr. Howard moved his family to the Central Texas hamlet of Cross Plains, and there the family would stay for the rest of Howard's life.[1][5][21] Howard's father bought a house in the town with a cash down payment and made extensive renovations. He added modern conveniences such as indoor plumbing, electricity, and gas, as well as building extensions onto the house itself. This may have been intended as a gift to Howard's mother as the expensive work made it one of the better homes by local standards.[22] That same year, sitting in a library in New Orleans while his father took medical courses at a nearby college, Howard discovered a book concerned with the scant fact and abundant legends surrounding an indigenous culture in ancient Scotland called the Picts.[23][24] Named for the tattoos they decorated themselves with and bitter enemies of encroaching Roman legions, the Picts fired Howard's imagination and crystallized in him a love for barbarians and outsiders from civilization who lived lives of great hardship and struggle but also great freedom and verve. From then on, the Picts became a muse of sorts, appearing in various guises throughout all the many genres Howard wrote in, and helping to thematically tie his work together.[24]

"I'll say one thing about an oil boom; it will teach a kid that Life's a pretty rotten thing as quick as anything I can think of."

—Robert E. Howard in a letter to Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright, Summer 1931.[25]

In 1920, on February 17, the Vestal Well within the limits of Cross Plains came in a gusher and Cross Plains became an oil boomtown. Thousands of people arrived in the town looking for oil wealth. New businesses sprang up from scratch and the crime rate increased to match. Howard hated the boom and despised the people who came with it.[26] He was already poorly disposed towards oil booms as they were the cause of the constant traveling in his early years but this was aggravated by what he perceived to be the effect oil booms had on towns. In a letter to H. P. Lovecraft in October 1930, Howard wrote, "I've seen whole towns debauched by an oil boom and boys and girls go to the devil whole-sale. I've seen promising youths turn from respectable citizens to dope-fiends, drunkards, gamblers and gangsters in a matter of months."[27] Cross Plains' population quickly grew from 1,500 to 10,000, it suffered overcrowding and the amount of traffic ruined its unpaved roads. Crime increased with regular fights breaking out, theft, gambling and even highwaymen. The added wealth meant an increased disposable income and an increase in vice crime. However, the town also used its new wealth on civic improvements, which included a new school, an ice manufacturing plant, and new hotels.[28]

At fifteen Howard first sampled pulp magazines, especially Adventure and its star authors Talbot Mundy and Harold Lamb.[29][30] The next few years saw him creating a variety of series characters: El Borak (a Texan cross between John Rambo and T. E. Lawrence), a cowboy hero named The Sonora Kid, the puritan avenger Solomon Kane, and the last king of the Picts, Bran Mak Morn.[16][31] Soon the fifteen-year-old was submitting stories to pulps such as Adventure and Argosy.[17][32] Rejections piled up, and with no mentors or instructions of any kind to aid him, Howard became a writing autodidact, methodically studying the markets and tailoring his stories and style to each.

Brownwood

In the fall of 1922, when Howard was sixteen, he temporarily moved to a boarding house in the nearby city of Brownwood to complete his senior year of high school, accompanied by his mother (with his father visiting at weekends).[33][34][35] It was in Brownwood that he first met friends his own age who shared his interest not only for sports and history but also writing and poetry. The two most important of these, Tevis Clyde Smith and Truett Vinson, shared his Bohemian and literary outlook on life, and together they wrote amateur papers and magazines, exchanged long letters filled with poetry and existential thoughts on Life and Philosophy, and encouraged each other's writing endeavors. Through Vinson, Howard was introduced to The Tattler, the newspaper of the Brownwood High School. It was in this publication that Howard's stories were first printed. The December 1922 issue featured two stories, "'Golden Hope' Christmas" and "West is West," which won gold and silver prizes respectively.[16][35][36]

Howard graduated from high school in May 1923 and moved back to Cross Plains. He maintained contact with his friends by mail.[37] On his return to his home town, he engaged in a self-created regimen of exercise, including cutting down oak trees and chopping them into firewood every day, lifting weights, punching a bag and springing exercises; eventually building himself from a skinny teenager into a muscled, burly specimen.[38]

Howard Payne College

Howard spent his late teens working hated odd jobs around Cross Plains: picking cotton, branding yearlings, hauling garbage, working in grocery stores, office work, serving at a soda counter, public stenography, packing rods for a surveyor, and writing oil-field news. In 1924, Howard returned to Brownwood to take a stenography course at Howard Payne College, this time boarding with his friend Lindsey Tyson instead of his mother. Howard would have preferred a literary course but was not allowed to take one for some reason. Biographer Mark Finn suggests that his father refused to pay for such a non-vocational education.[9][39] In the week of Thanksgiving that year, and after years of rejection slips and near acceptances, he finally sold a short caveman tale titled "Spear and Fang", which netted him the sum of $16 and introduced him to the readers of a struggling pulp called Weird Tales.[16][17][40]

Now that his career in fiction had begun, Howard dropped out of Howard Payne College at the end of the semester and returned to Cross Plains. Shortly afterwards, he received notice that another story, "The Hyena," had been accepted by Weird Tales.[41] During the same period, Howard made his first attempt to write a novel, a loosely autobiographical book modeled on Jack London's Martin Eden and titled Post Oaks & Sand Roughs. The book was otherwise of middling quality and was never published in the author's lifetime but it is of interest to Howard scholars for the personal information it contains. Howard's alter ego in this novel is Steve Costigan, a name he would use more than once in the future. The novel was finished in 1928 but not published until long after his death.[42]

Odd Jobs

Weird Tales paid on publication, meaning that Howard had no money of his own at this time. To remedy this, he took a job writing oil news for the local newspaper Cross Plains Review at $5 per column. It was not until July 1925 that Howard received payment for his first printed story.[43][44] Howard lost his job at the newspaper in the same year and spent one month working in a post office before quitting over the low wages. His next job, at the Cross Plains Natural Gas Company, did not last long due to his refusal to be subservient to his boss. He did manual labor for a surveyor for a time before beginning a job as a stenographer for an oil company.[45][46]

Howard briefly attempted to start a musical career at this time but faced a succession of unreliable tutors before giving up. His first tutor was a wandering fiddler who taught the violin before skipping the county. He continued his lessons with a Scottish tutor, who died suddenly. His final violin tutor was a German swindler who was forced to leave town quickly while wanted by the police.[16]

In conjunction with his friend Tevis Clyde Smith he dabbled heavily in verse, writing hundreds of poems and getting dozens published in Weird Tales and assorted poetry journals (including the Daniel Baker Collegian, of which Smith was the editor). The best of these efforts remain classics, conjuring up the same blood-splattered, dark, mythic visions of war and rapine that his best stories do. Efforts to get a book of poems accepted by a mainstream publisher failed, however, with several editors recoiling at the brutal imagery and macabre subject matter.[47] Ultimately Howard judged poetry writing a luxury he could not afford, and after 1930 he wrote little verse, instead dedicating his time to short stories and higher-paying markets.[48] Nevertheless, as a result of this apprenticeship, his stories increasingly took on the aura of "prose-poems" filled with hypnotic, dreamy imagery and a power lacking in most other pulp efforts of the time.[49]

Further story sales to Weird Tales were sporadic but encouraging, and soon Howard was a regular in the magazine. His first cover story was for "Wolfshead", a werewolf yarn published when he was only twenty. This story almost did not see print when the magazine appeared to lose the only copy. Without a duplicate, Howard worked through the night re-typing the story from memory. Almost the entire original was found, however, although the second version was used for the first page and Howard earned an extra $10 for his effort.[44][47][48]

On reading "Wolfshead" in Weird Tales Howard became dismayed with his writing. He quit his stenographer's job to work at Robertson's Drug Store, where he rose to become Head Soda Jerk on $80 per week. However, he resented the job itself and worked such long hours every day of the week that he became ill. He relaxed by visiting the Neeb Ice House, to which he was introduced by an oil-field worker befriended at the drug store, to drink and began to take part in boxing matches. These matches became an important part of his life; the combination of boxing and writing provided an outlet for his frustrations and anger.[44][48][50][51]

Return to Howard Payne College

In August 1926, Howard quit his exhausting job at the drug store and, in September, returned to Brownwood to complete his bookkeeping course.[48] It was during this August that he began working on the story that would become "The Shadow Kingdom", one of the most important works of his career. In May 1927, after having to return home due to contracting measles and then being forced to retake the course, Howard passed his exams. While waiting for the official graduation in August, he returned to writing, including a re-write of "The Shadow Kingdom." He rewrote it again in August and submitted it to Weird Tales in September.[52] This story was an experiment with the entire concept of the "weird tale" horror fiction as defined by practitioners such as Edgar Allan Poe, A. Merritt, and H. P. Lovecraft; mixing elements of fantasy, horror and mythology with historical romance, action and swordplay into thematic vehicles never before seen, a new style of tale which ultimately became known as "sword and sorcery".[nb 4][nb 5][53][54] Featuring Kull, a barbarian precursor to later Howard heroes such as Conan, the tale hit Weird Tales in August 1929 and received fanfare from readers. Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright bought the story for $100, the most Howard had earned for a story at this time, and several more Kull stories followed. However, all but two were rejected, convincing Howard not to continue the series.[55][56]

In 1929, at the age of twenty-three, Howard had regular markets for several series, including Kull, Solomon Kane and Sailor Steve Costigan. With this, Howard quit taking college courses and became a full-time writer.[57][58]

Parents

During Howard's youth his parents' relationship began to break down. The Howard family had problems with money which may have been exacerbated by Isaac Howard investing in get-rich-quick schemes. Hester Howard, meanwhile, came to believe that she had married below herself. Soon the pair were actively fighting. Hester did not want Isaac to have anything to do with their son.[59]

During Howard's youth his mother Hester had a particularly strong influence on his intellectual growth.[14][20] Known throughout her family as a kind and giving woman—she had selflessly spent her early years helping a variety of sick relatives, contracting tuberculosis in the process. It was she who instilled in her son a deep love of poetry and literature, recited verse daily and supported him unceasingly in his efforts to write.[60] Howard never forgot her many kindnesses both to himself and his extended family, and her growing sickness and invalidity did much to cement his view of existence as heartless, unfair, and ultimately futile.

Early influences on Howard

Talking to aging Civil War veterans and Texas Rangers, listening to grisly ghost stories told by his grandmother and ex-slaves, and visiting old forts and historical sites all had a strong influence on his personality.[61][62] By the time he reached his teens, Howard had soaked in the dying of the Frontier, the bloody history and legends of the American Southwest, and the art of the tall tale.[12][63]

Mary Bohannon

Mary Bohannon was a cook when the Howard family lived in Bagwell, Texas during 1913–1914. She told ghost stories to the young Robert E. Howard, one of which became the basis for "Pigeons from Hell", one of Howard's most acclaimed works. Bohannon was born a slave in Kentucky sometime between 1825 and 1836.[64] She came to Bagwell area when her owners, Henry and Pauline Bohannon moved to Red River County in the 1850s.[64] Following the American Civil War, the white Bohannons left the area but Mary remained.[64] She sold her house in 1907 and both the 1910 and 1920 censuses state that she was living with the family of Lottie Hite Dennis.[64] She may have been working as a cook in general or possibly as the Howard family's cook. Mary Bohannon dies February 27, 1921.[64]

Howard mentioned Bohannon in a 1930 letter to H. P. Lovecraft:

As regards African-legend sources, I well remember the tales I listened to and shivered at, when a child in the "piney woods" of East Texas, where Red River marks the Arkansaw and Texas boundaries. There were quite a number of old slave darkies still living then. The one to whom I listened most was the cook, old Aunt Mary Bohannon.[64]

Slightly later in the letter, he recounts the story that would become the basis of "Pigeons from Hell":

Another tale she told that I have often met with in negro-lore. The setting, time and circumstances are changed by telling, but the tale remains basically the same. Two or three men—usually negroes—are travelling in a wagon through some isolated district—usually a broad, deserted river-bottom. They come on to the ruins of a once thriving plantation at dusk, and decide to spend the night in the deserted plantation house. This house is always huge, brooding and forbidding, and always, as the men approach the high columned verandah, through the high weeds that surround the house, great numbers of pigeons rise from their roosting places on the railing and fly away. The men sleep in the big front-room with its crumbling fire-place, and in the night they are awakened by a jangling of chains, weird noises and groans from upstairs. Sometimes footsteps descend the stairs with no visible cause. Then a terrible apparition appears to the men who flee in terror.[64]

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Grin (2006, pp. 13–18): Contains facsimile reproductions of Howard's birth certificate and death record.

- ↑ Finn (2006, p. 26) notes that the birth record incorrectly shows Howard's birthdate as January 24, in addition to altering his mother's age.

- ↑ Burke (3rd paragraph): notes that Howard celebrated his birthday on the 22nd rather than the 24th, as recorded in Parker County records. His father also gave his birthday as January 22.

- ↑ Herron, Joshi & Dziemianowicz (2005, p. 1095): "Critical consensus, however, unfailingly places the birth of sword-and-sorcery with the publication of 'The Shadow Kingdom' (August 1929), in which Howard introduced the brooding figure of King Kull, ruling over the fading land of Valusia in a Pre-Cataclysmic Age when Atlantis is but newly risen from the waves."

- ↑ Gramlich & Westfahl (2005, p. 780): "The term 'sword and sorcery' was coined by Fritz Leiber but the genre was pioneered by Robert E. Howard, a Texas pulp writer who combined fantasy, history, horror, and the Gothic to create the Hyborian Age and such characters as Conan the Conqueror and Kull."

Citations

- 1 2 3 Lord (1976, p. 71)

- ↑ Finn (2006, p. 26)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 21–26)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 30–41)

- 1 2 Burke (¶ 5)

- 1 2 3 Louinet (2002, Arrival in Bagwell)

- ↑ Louinet (2002, Conclusion)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 41–42)

- 1 2 Burke (¶ 11)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 12, 49–50)

- ↑ Finn (2006, p. 35)

- 1 2 Burke (¶ 8)

- ↑ Lord (1976, pp. 75–76)

- 1 2 3 Burke (¶ 7)

- ↑ Finn (2006, p. 50)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lord (1976, p. 72)

- 1 2 3 4 Burke (¶ 9)

- ↑ Finn (2006, p. 41)

- ↑ Eng (2000, p. 24)

- 1 2 Finn (2006, p. 42)

- ↑ Finn (2006, p. 43)

- ↑ Finn (2006, p. 46)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 87, 92)

- 1 2 Burke (¶ 19)

- ↑ Finn (2006, p. 12)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 16–17)

- ↑ Finn (2006, p. 17)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 47–49)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 50–51)

- ↑ Louinet (2003, pp. 347–348)

- ↑ Burke (¶ 18–20)

- ↑ Finn (2006, p. 51)

- ↑ Lord (1976, pp. 71–72)

- ↑ Finn (2006, p. 73)

- 1 2 Burke (¶ 10)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 75–76)

- ↑ Lord (1976, pp. 71–72, 77–78)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 128–129)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 219)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 87–88)

- ↑ Finn (2006, p. 91)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 91–101, 117–119)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 93–94)

- 1 2 3 Burke (¶ 13)

- ↑ Lord (1976, p. 74)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 96–98)

- 1 2 Finn (2006, p. 98)

- 1 2 3 4 Lord (1976, p. 75)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 104–105)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 99–101)

- ↑ Burke (¶ 27)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 105–108)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 113–115)

- ↑ Burke (¶ 22)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 113)

- ↑ Burke (¶ 24)

- ↑ Finn (2006, p. 120)

- ↑ Burke (¶ 15)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 39–40)

- ↑ Finn (2006, p. 34)

- ↑ Lord (1976, p. 73)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 33, 59–60)

- ↑ Finn (2006, pp. 57–58, 65–71)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Louinet (2002, "Aunt" Mary Bohannon)

References

- Burke, Rusty, "A Short Biography of Robert E. Howard", The Robert E. Howard United Press Association

- Finn, Mark (2006), Blood & Thunder, Monkeybrain, Inc., ISBN 1-932265-21-X

- Gramlich, Charles (2005), Westfahl, Gary, ed., The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy, 2, Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-32952-4

- Grin, Leo (January 2006), "Birth and Death", The Cimmerian, 3 (1): 13–18, ISSN 1548-3398

- Herron, Don (2005), Joshi, S. T.; Dziemianowicz, Stefan, eds., Supernatural Literature of the World, 3, Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-32774-2

- Lord, Glenn (1976), The Last Celt, Berkley Windhover Books, ISBN 978-0-425-03630-3

- Louinet, Patrice (2002), "Pigeons from... Bagwell", Dwelling in Dark Valley, The Robert-E-Howard: Electronic Amateur Press Association, 1 (4)