Eadbald of Kent

| Eadbald | |

|---|---|

Coin of Eadbald of Kent | |

| King of Kent | |

| Reign | 24 February 616 – 20 January 640 |

| Predecessor | Æthelberht |

| Successor | Eorcenberht |

| Died | 20 January 640 |

| Spouse | Emma of Austrasia |

| Issue |

Eormenred Eorcenberht Eanswith |

| Father | Æthelberht |

| Mother | Bertha |

Eadbald (Old English: Ēadbald) was King of Kent from 616 until his death in 640. He was the son of King Æthelberht and his wife Bertha, a daughter of the Merovingian king Charibert.[1] Æthelberht made Kent the dominant force in England during his reign and became the first Anglo-Saxon king to convert to Christianity from Anglo-Saxon paganism. Eadbald's accession was a significant setback for the growth of the church, since he retained his indigenous paganism and did not convert to Christianity for at least a year, and perhaps for as much as eight years. He was ultimately converted by either Laurentius or Justus, and separated from his first wife, who had been his stepmother, at the insistence of the church. Eadbald's second wife was Emma, who may have been a Frankish princess. She bore him two sons, Eormenred and Eorcenberht, and a daughter, Eanswith.

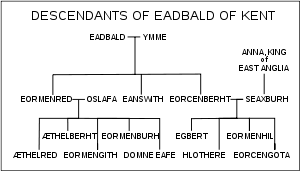

Eadbald's influence was less than his father's, but Kent was powerful enough to be omitted from the list of kingdoms dominated by Edwin of Northumbria. Edwin's marriage to Eadbald's sister, Æthelburg, established a good relationship between Kent and Northumbria which appears to have continued into Oswald's reign. When Æthelburg fled to Kent on Edwin's death in about 633, she sent her children to Francia for safety, fearing the intrigues of both Eadbald and Oswald. The Kentish royal line made several strong diplomatic marriages over the succeeding years, including the marriage of Eanflæd, Eadbald's niece, to Oswiu, and of Eorcenberht to Seaxburh, daughter of King Anna of East Anglia.

Eadbald died in 640 and was buried in the Church of St Mary, which he had built in the precincts of the monastery of St Peter and St Paul in Canterbury (a church later incorporated within the Norman edifice of St Augustine's).[1] At that time, his relics were translated for reburial in the south transept ca. A.D. 1087.[2]

He was succeeded by Eorcenberht. Eormenred may have been his oldest son, but if he reigned at all it was only as a junior king.

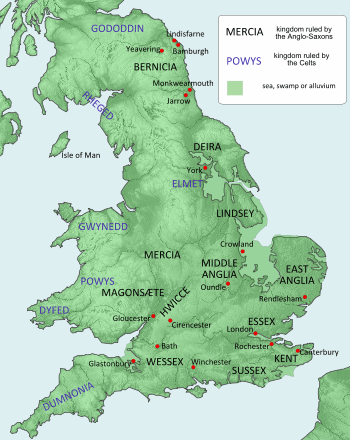

Early Kent and early sources

Settlement of Kent by continental peoples, primarily Jutes, was complete by the end of the sixth century.[3] Eadbald's father, Æthelberht, probably came to the throne in about 589 or 590, though the chronology of his reign is very difficult to determine accurately.[4] Æthelberht was recorded by the early chronicler Bede as having overlordship, or imperium, over other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.[5] This dominance led to wealth in the form of tribute, and Kent was a powerful kingdom at the time of Æthelberht's death in 616, with trade well-established with the European mainland.[6]

Roman Britain had become fully Christianized, but the Anglo-Saxons retained their native faith. In 597 Augustine was sent by Pope Gregory I to England to convert them to Christianity. Augustine landed in eastern Kent, and soon managed to convert Æthelberht, who gave Augustine land in Canterbury. Two other rulers, Sæberht, king of Essex, and Rædwald, king of East Anglia, were converted through Æthelberht's influence.[7][8]

An important source for this period in Kentish history is The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written in 731 by Bede, a Benedictine monk from Northumbria. Bede was primarily interested in the Christianization of England, but he also provides substantial information about secular history, including the reigns of Æthelberht and Eadbald. One of Bede's correspondents was Albinus, abbot of the monastery of St. Peter and St. Paul (subsequently renamed St. Augustine's) in Canterbury. A series of related texts known as the Legend of St Mildrith provides additional information about events in the lives of Eadbald's children and throws some light on Eadbald himself. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a collection of annals assembled in about 890 in the kingdom of Wessex, also provides information. Other sources include papal letters, regnal lists of the kings of Kent, and early charters. Charters were documents drawn up to record grants of land by kings to their followers or to the church, and they provide some of the earliest documentary sources in England. None survive in original form from Eadbald's reign, but some later copies exist.[9]

Ancestry and immediate family

The ancestry of Æthelberht, Eadbald's father, is given by Bede, who states that he was descended from the legendary founder of Kent, Hengist. However, historians believe that Hengist and his brother Horsa were probably mythical figures.[10] It is known that Æthelberht married twice as Eadbald married his step-mother after his father's death, to the consternation of the church.[11]

Eadbald had a sister, Æthelburg, who was probably also the child of Bertha. Æthelburg married Edwin, King of Northumbria, one of the dominant Anglo-Saxon kings of the seventh century. It is possible that there was another brother, named Æthelwald:[12] the evidence for this is a papal letter to Justus, archbishop of Canterbury from 619 to 625, in which a king named Aduluald is referred to, and who is apparently different from Audubald, which refers to Eadbald. There is no agreement among modern scholars on how to interpret this: "Aduluald" might be intended as a representation of "Æthelwald", and hence this may be an indication of another king, perhaps a subking of west Kent;[13] or it may be merely a scribal error which should be read as referring to Eadbald.[14]

Archbishop Laurence of Canterbury persuaded Eadbald to accept Christianity and give up his wife.[1] He then remarried, and his second wife, according to Kentish tradition recorded in the 'Kentish Royal Legend', was a woman named Ymme of Frankish royal blood, though recently it has been suggested that she may have instead been the daughter of Erchinoald, mayor of the palace in Neustria, the western part of Francia.[15][16]

East and West Kent

The surviving regnal lists show only one king reigning at a time in Kent, but subkingdoms were common among the Anglo-Saxons and from the reign of Hlothhere, in the late seventh century, there is evidence that Kent was usually ruled by two kings, though often one is clearly dominant. It is less clear that this is the case before Hlothhere. Forged charters preserve a tradition of Eadbald ruling during his father's reign, presumably as a subking over west Kent. The papal letter that has been interpreted as indicating the existence of Æthelwald, a brother of Eadbald's, refers to Æthelwald as a king; if he existed, he would presumably have been a junior king to Eadbald.[13]

The two kingdoms within Kent were east and west Kent. Western Kent has fewer archaeological finds from the earliest periods than east Kent, and the eastern finds are somewhat distinct in character, showing Jutish and Frankish influence. The archaeological evidence, combined with the known political division into two kingdoms, makes it likely that the origin of the subkingdoms was the conquest of the western half by the eastern, which would have been the first area settled by the invaders.[17]

Accession and pagan reaction

| |

| O: Bust of Eadbald right. AVDV[ARLD REGES] | R: Cross on globe within wreath. ++IÞNNBALLOIENVZI |

| Gold thrymsa of Eadbald of Kent, London (?), 616–40 | |

Eadbald came to the throne on the death of his father on 24 February 616, or possibly 618. Although Æthelberht had been Christian since about 600 and his wife Bertha was also Christian, Eadbald was a pagan. Bertha died some time before Eadbald's accession, and Æthelberht remarried. The name of Æthelberht's second wife is not recorded, but it seems likely that she was a pagan, since on his death she married Eadbald, her stepson: a marriage between a stepmother and stepson was forbidden by the church.[4][5]

Bede records that Eadbald's repudiation of Christianity was a "severe setback" to the growth of the church. Sæberht, the king of Essex, had become a Christian under Æthelberht's influence, but on Sæberht's death, at about the same time, his sons expelled Mellitus, the bishop of London.[5] According to Bede, Eadbald was punished for his faithlessness by "frequent fits of insanity", and possession by an "evil spirit" (perhaps referring to epileptic fits),[5][18] but was eventually persuaded to abandon paganism and give up his wife.[14][19] Eadbald's second wife, Ymme, was a Frank,[16] and it is possible that Kent's strong connections with Francia were a factor in the King's conversion. The missionaries in Canterbury seem to have had Frankish support.[14] In the 620s, Eadbald's sister Æthelburg came to Kent, but sent her children to the court of King Dagobert I in Francia; in addition to the diplomatic connections, trade with the Franks was important to Kent. It is thought likely that Frankish pressure had been influential in persuading Æthelberht to become Christian, and Eadbald's conversion and marriage to Ymme are likely to have been closely connected diplomatic decisions.[14][20]

Two graves from a well-preserved sixth and seventh-century Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Finglesham have yielded a bronze pendant and a gilt buckle with designs that are related to each other and may be symbolic of religious activity involving the Germanic deity Woden. These objects probably date from the period of the pagan reaction.[21]

Bede's account

Bede's account of Eadbald's rejection of the church and subsequent conversion is quite detailed but not without some internal inconsistency.[14] Bede's version of events are laid out as follows:

- 24 February 616: Æthelberht dies and Eadbald succeeds.[5]

- 616: Eadbald leads a pagan reaction to Christianity. He marries his stepmother, contrary to church law, and refuses baptism. At about this time Mellitus, bishop of London, is expelled by the sons of Sæberht in Essex and goes to Kent.[5]

- 616: Mellitus and Justus, bishop of Rochester, leave Kent for Francia.[5]

- 616/617: Some time after Mellitus and Justus depart, Laurence, the archbishop of Canterbury, plans to leave for Francia but has a vision in which St Peter scourges him. In the morning he shows the scars to Eadbald who is converted to Christianity as a result.[19]

- 617: Justus and Mellitus both return from Francia "the year after they left". Justus is restored to Rochester.[5]

- c. 619: Laurence dies, and Mellitus becomes archbishop of Canterbury.[22]

- 619–624: Eadbald builds a church which is consecrated by Archbishop Mellitus.[19]

- 24 April 624: Mellitus dies and Justus succeeds him as archbishop of Canterbury.[22]

- 624: After Justus's succession, Pope Boniface writes to him to say that he has heard in letters from King Aduluald (possibly a scribal error for Eadbald) of the king's conversion to Christianity. Boniface sends the pallium with this letter, adding that it is only to be worn when celebrating "the Holy Mysteries".[23]

- By 625 Edwin of Deira, king of Northumbria, asks for the hand in marriage of Æthelburg, Eadbald's sister. Edwin is told he must allow her to practice Christianity and must consider baptism himself.[24]

- 21 July 625: Justus consecrates Paulinus bishop of York.[24]

- July or later in 625: Edwin agrees to the terms and Æthelburg travels to Northumbria, accompanied by Paulinus.[24]

- Easter 626: Æthelburg gives birth to a daughter, Eanflæd.[24]

- 626: Edwin completes a military campaign against the West Saxons.[24] At "about this time" Boniface writes to both Edwin and Æthelburg. The letter to Edwin urges him to accept Christianity and refers to the conversion of Eadbald. The letter to Æthelburg mentions that the pope has recently heard the news of Eadbald's conversion and encourages her to work for the conversion of her husband, Edwin.[25]

Alternative chronology

Although Bede's narrative is widely accepted, an alternative chronology has been proposed by D.P. Kirby. Kirby points out that Boniface's letter to Æthelburg makes it clear that the news of Eadbald's conversion is recent, and that it is unthinkable that Boniface would not have been kept up to date on the status of Eadbald's conversion. Hence Eadbald must have been converted by Justus, as is implied by Boniface's letter to Justus. The pallium accompanying that letter indicates Justus was archbishop by that time, and the duration of Mellitus's archiepiscopate means that even if Bede's dates are somewhat wrong in other particulars, Eadbald was converted no earlier than 621, and no later than April 624, since Mellitus consecrated a church for Eadbald before his death in that month. The account of Laurence's miraculous scourging by St Peter can be disregarded as a later hagiographical invention of the monastery of St Augustine.[14]

As mentioned above, it has been suggested that King "Aduluald" in the letter to Justus is a real king Æthelwald, perhaps a junior king of west Kent. In that case it would appear that Laurence converted Eadbald, and Justus converted Æthelwald.[13] It has also been suggested that the pallium did not indicate Justus was archbishop, since Justus is told the limited circumstances in which he may wear it; however, the same phrasing occurs in the letter conveying the pallium to Archbishop Augustine, also quoted in Bede. Another possibility is that the letter was originally two letters. In this view, Bede has conflated the letter conveying the pallium with the letter congratulating Justus on the conversion, which according to Bede's account was seven or so years earlier; but the grammatical details on which this suggestion is based are not unique to this letter, and as a result it is usually considered to be a single composition.[14]

The letter to Æthelburg makes it clear that she was already married at the time the news of Eadbald's conversion reached Rome. This is quite inconsistent with the earlier date Bede gives for Eadbald's acceptance of Christianity, and it has been suggested in Bede's defence that Æthelburg married Edwin substantially earlier and stayed in Kent until 625 before travelling to Rome, and that the letter was written while she was in Kent. However, it would appear from Boniface's letter that Boniface thought of Æthelburg as being at her husband's side. It also appears that the letter to Justus was written after the letters to Edwin and Æthelburg, rather than before, as Bede has it; Boniface's letter to Edwin and Æthelburg indicates he had the news from messengers, but when he wrote to Justus he had heard from the king himself.[14]

The story of Æthelburg's marriage being dependent on Edwin allowing her to practice her faith has been questioned, since revising the chronology makes it likely, though not certain, that the marriage was arranged before Eadbald's conversion. In this view, it would have been the church that objected to the marriage, and Æthelburg would have been Christian before Eadbald's conversion. The story of Paulinus's consecration is also problematic as he was not consecrated until at least 625 and possibly later, which is after the latest possible date for Æthelburg's marriage. However, it may be that he traveled to Northumbria prior to his consecration and only later became bishop.[14]

A revised chronology of some of these events follows, taking the above considerations into account.

- 616: Eadbald leads a pagan reaction to Christianity.

- 616: Mellitus and Justus, bishop of Rochester, leave Kent for Francia.[5]

- c. 619: Laurence dies, and Mellitus becomes archbishop of Canterbury.[19]

- Early 624?: Justus converts Eadbald. Messengers go to Rome.[23] Also at about this time Æthelburg's marriage to Edwin is arranged, perhaps before the conversion.[24] Eadbald builds a church, and Mellitus consecrates it.[19]

- 24 April 624: Mellitus dies and Justus succeeds him as archbishop of Canterbury.[22]

- Mid 624: Edwin agrees to the marriage terms and Æthelburg travels to Northumbria, accompanied by Paulinus.[24]

- Later 624: the pope receives news of Eadbald's conversion and writes to Æthelburg and Edwin.[25]

- Still later 624: the pope hears from Eadbald of his conversion, and also hears of Mellitus's death. He writes to Justus to send him the pallium.[23]

- 21 July 625 or 626: Justus consecrates Paulinus bishop of York.[24]

This timeline extends the duration of the pagan reaction from less than a year, in Bede's narrative, to about eight years. This represents a more serious setback for the church.[14]

Relations with other English kingdoms and church affairs

Eadbald's influence over other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms was less than Æthelberht's. Eadbald's reduced power is apparent in his inability to restore Mellitus to the see of London: in Bede's words, his authority in Essex "was not so effective as that of his father".[19] However, Kentish power was still sufficient to make alliance with Eadbald's relatives attractive to other kingdoms. Edwin's marriage to Eadbald's sister, Æthelburg, was probably also motivated by a desire to gain better access to communications with the continent.[26] The relationship would have been valuable to Eadbald, too; it may have been as a result of this alliance that Edwin's overlordship of Britain did not include Kent.[5][12][24] Another factor in Edwin's treatment of Kent may have been the location of the archbishopric in Canterbury: Edwin was well aware of the importance of Canterbury's metropolitan status, and at one time planned to make York an archbishopric too, with Paulinus as the planned first incumbent.[27] Paulinus eventually returned to Kent, where at Eadbald's and Archbishop Honorius's request he became bishop of Rochester, and York was not made an archbishopric for another century.[28][29] Within a year of Edwin's death in 633 or 634,[29] Oswald took the throne of Northumbria, and it seems likely that his relations with Eadbald were modelled on Edwin's. Oswald's successor, Oswiu, married Eanflæd, who was Edwin's daughter and Eadbald's niece, thereby gaining both Deiran and Kentish connections.[30][31]

Eadbald and Ymme had a daughter, Eanswith (who founded the very first nunnery on English soil at Folkestone, 15 miles from Canterbury), and two sons, Eorcenberht and Eormenred. Eormenred was the older of the two, and may have held the title of regulus, perhaps implying that he held the junior kingship of Kent. He appears to have died before his father, leaving Eorcenberht to inherit the throne.[16][32] An additional son, Ecgfrith, is mentioned in a charter of Eadbald's, but the charter is a forgery, probably dating from the eleventh century.[33][34]

Several of Eadbald's near relatives were involved in diplomatic marriages. King Anna of East Anglia married his daughter, Seaxburh, to Eorcenberht, and their daughter Eormenhild married Wulfhere of Mercia, one of the most powerful kings of his day. Eanflæd, Eadbald's niece, married Oswiu, king of Northumbria and the last of the northern Angles Bede listed as holding imperium over southern England. Eadbald's granddaughter Eafe married Merewalh, king of the Magonsæte.[35]

Trade and connections to the Franks

There is little documentary evidence about the nature of trade in Eadbald's reign. It is known that the kings of Kent had established royal control of trade in the late seventh century, but it is not known how early this control began. There is archaeological evidence that suggests that the royal influence predates any of the written sources, and it may have been Eadbald's father, Æthelberht, who took control of trade away from the aristocracy and made it a royal monopoly. The continental trade provided Kent access to luxury goods, which was an advantage in trading with the other Anglo-Saxon nations, and the revenue from trade was important in itself.[36] Kent traded locally made glass and jewelry to the Franks; Kentish goods have been found as far south as the mouth of the Loire, south of Brittany. There was probably also a flourishing slave trade. The wealth this commerce brought to Kent may have been the basis of the continuing, though diminished, importance of Kent in Eadbald's reign.[6]

Coins were probably first minted in Kent in Æthelberht's reign, though none bear his name. These early golden coins were probably the shillings (scillingas in Old English) that are mentioned in Æthelberht's laws.[36] The coins are also known to numismatists as "thrymsas".[37] Thrymsas are known from Eadbald's reign; but few are known that carry his name: one such was minted at London and inscribed "AVDVARLD". It has been suggested that kings did not have a monopoly on the production of coinage at that time.[38]

Connections with Francia went beyond trade and the royal marriages Æthelberht and Eadbald made with Frankish princesses. Eadbald's granddaughter, Eorcengota, became a nun at Faremoutiers, and his great-granddaughter, Mildrith, was a nun at Chelles. When Edwin was killed in about 632, Æthelburg, escorted by Paulinus, fled by sea to Eadbald's court in Kent, but in a further sign of her family's ties across the channel she sent her children to the court of King Dagobert I of the Franks, to keep them safe from the intrigues of Eadbald and Oswald of Northumbria.[20][28][30]

Succession

Eadbald died in 640, and according to most versions of the Kentish Royal Legend was succeeded solely by his son Eorcenberht. However, an early text (Caligula A.xiv) refers to Eormenred as 'king', suggesting either he was a junior king under Eorcenberht, or had a shared kingship.[16] One suggestion is that the some other version of events in the 'legend', which give him no title, may have been an attempt to discredit royal claimants from Eormenred's line.[39]

Notes

- 1 2 3 S. E. Kelly, Eadbald, Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- ↑ See, e.g., the guide booklet to St. Augustine's Abbey (London: English Heritage, 1997), 20, 25.

- ↑ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 26.

- 1 2 Kirby, Earliest English Kings, pp. 31–33, provides an extended discussion of the chronology of Æthelberht's reign.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Bede, Ecclesiastical History, bk. II, ch. 5, p. 111.

- 1 2 Campbell et al., The Anglo-Saxons, p. 44.

- ↑ Bede, Ecclesiastical History, bk. I, ch. 25, p. 74.

- ↑ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, pp. 30–37.

- ↑ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 25.

- ↑ Barbara Yorke, Kent, kings of, Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- ↑ S. E. Kelly, Æthelberht I, Oxford Online Dictionary of National Biography, 2004

- 1 2 Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, pp. 32–33.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Kirby, Earliest English Kings, pp. 37–42.

- ↑ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 4 Rollason, Mildrith Legend, p. 9.

- ↑ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 27.

- ↑ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 175.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bede, Ecclesiastical History, bk. II, ch. 6, p. 113.

- 1 2 Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 39.

- ↑ Commentary, and images of both objects, can be found in S. Chadwick Hawkes, "Finglesham. A Cemetery in East Kent" and "The Archaeology of Conversion: Cemeteries", both in Campbell, The Anglo-Saxons, pp. 24–25 and 48–49.

- 1 2 3 Bede, Ecclesiastical History, bk. II, ch. 7, p. 114.

- 1 2 3 Bede, Ecclesiastical History, bk. II, ch. 8, p. 116.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bede, Ecclesiastical History, bk. II, ch. 9, p. 117.

- 1 2 Bede, Ecclesiastical History, bk. II, ch. 10, p. 120.

- ↑ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p.61.

- ↑ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p.79.

- 1 2 Bede, Ecclesiastical History, bk. II, ch. 20, p. 141.

- 1 2 Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p.80.

- 1 2 Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p.88.

- ↑ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p.92.

- ↑ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p.35.

- ↑ See Ecgfrith 1 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England. Retrieved 9 January 2015. The charter itself can be seen at "Anglo-Saxons.net S 6". Sean Miller. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ↑ Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 141.

- ↑ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p.43.

- 1 2 Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 40.

- ↑ M.A.S. Blackburn, "Coinage", in Lapidge, Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 113–116.

- ↑ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p.44.

References

Primary sources

- Bede (1991). D.H. Farmer, ed. Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Translated by Leo Sherley-Price. Revised by R.E. Latham. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044565-X.

Secondary sources

- Campbell, James; John, Eric; Wormald, Patrick (1991). The Anglo-Saxons. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-014395-5.

- Kirby, D.P. (1992). The Earliest English Kings. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-09086-5.

- Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Rollason, D.W. (1982). The Mildrith Legend: A Study in Early Medieval Hagiography in England. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Leicester University Press/Humanities Press, Inc. ISBN 0-7185-1201-4.

- Stenton, Frank M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-821716-1.

- Yorke, Barbara (1990). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London: Seaby. ISBN 1-85264-027-8.

External links