Dysplasia

| -plasia and -trophy |

|---|

|

|

Dysplasia (from Ancient Greek δυσ- dys-, "bad" or "difficult" and πλάσις plasis, "formation") is an ambiguous term used in pathology to refer to an abnormality of development or an epithelial anomaly of growth and differentiation (epithelial dysplasia).[1]

The terms hip dysplasia, fibrous dysplasia, renal dysplasia refer to an abnormal development, at macroscopic or microscopical level.

Myelodysplastic syndromes, or dysplasia of blood-forming cells, show increased numbers of immature cells in the bone marrow, and a decrease in mature, functional cells in the blood.

Epithelial dysplasia

Epithelial dysplasia consists of an expansion of immature cells (such as cells of the ectoderm), with a corresponding decrease in the number and location of mature cells. Dysplasia is often indicative of an early neoplastic process. The term dysplasia is typically used when the cellular abnormality is restricted to the originating tissue, as in the case of an early, in-situ neoplasm.

Dysplasia, in which cell maturation and differentiation are delayed, can be contrasted with metaplasia, in which cells of one mature, differentiated type are replaced by cells of another mature, differentiated type.

Examples

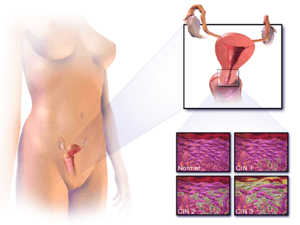

Examples of dysplasia include epithelial dysplasia of the cervix (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia – a disorder commonly detected by an abnormal pap smear) consisting of an increased population of immature (basal-like) cells which are restricted to the mucosal surface, and have not invaded through the basement membrane to the deeper soft tissues. Analogous conditions include vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia.

Screening

Some tests which detect cancer could be called "screening for epithelial dysplasia". The principle behind these tests is that physicians expect dysplasia to occur at the same rate in a typical individual as it would in many other people. Because of this, researchers design screening recommendations which assume that if a physician can find no dysplasia at certain time, then doing testing before waiting until new dysplasia could potentially develop would be a waste of medical resources for the patient and the healthcare provider because the chances of detecting anything is extremely low.

Some examples of this in practice are that if a patient whose endoscopy did not detect dysplasia on biopsy during screening for Barrett's esophagus, then research shows that there is little chance of any test detecting dysplasia for that patient within three years.[2][3][4]

Individuals at average-risk for colorectal cancer should have another screening after ten years if they get a normal result and after five years if they have only 1-2 adenomatous polyps removed.[2][5][6][7]

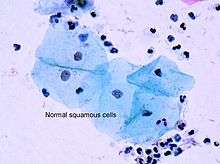

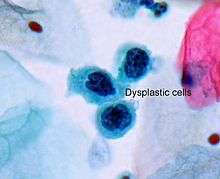

Microscopic changes

Dysplasia is characterised by four major pathological microscopic changes:

- Anisocytosis (cells of unequal size)

- Poikilocytosis (abnormally shaped cells)

- Hyperchromatism (excessive pigmentation)[8]

- Presence of mitotic figures (an unusual number of cells which are currently dividing).[9]

Dysplasia vs. carcinoma in situ vs. invasive carcinoma

These terms are related since they represent three stages in the progression of many malignant tumors of the epithelium. The likelihood of the development to cancer is related to the degree of dysplasia.[10]

- Dysplasia is the earliest form of pre-cancerous lesion which pathologists can recognize in a pap smear or in a biopsy. Dysplasia can be low grade or high grade (see "Carcinoma in situ" below). The risk of low grade dysplasia transforming into high grade dysplasia, and eventually cancer, is low. Treatment is usually straightforward. High grade dysplasia represents a more advanced progression towards malignant transformation.

- Carcinoma in situ, meaning "cancer in place", represents the transformation of a neoplastic lesion to one in which cells undergo essentially no maturation, and thus may be considered cancer-like. In this state, epithelial cells have lost their tissue identity and have reverted to a primitive cell form that grows rapidly and with abnormal regulation for the tissue type. However, this form of cancer remains localized, and has not invaded past the basement membrane into tissues below the surface.

- Invasive carcinoma is the final step in this sequence. It is a cancer which has invaded beyond the basement membrane and has potential to metastasize (spread to other parts of the body). Invasive carcinoma can usually be treated, but not always successfully. However, if it is left untreated, it is almost always fatal.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "dysplasia" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- 1 2 American Gastroenterological Association, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF), Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Gastroenterological Association, retrieved August 17, 2012

- ↑ American Gastroenterological Association; Spechler, S. J.; Sharma, P.; Souza, R. F.; Inadomi, J. M.; Shaheen, N. J. (2011). "American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the Management of Barrett's Esophagus". Gastroenterology. 140 (3): 1084–1091. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.030. PMID 21376940.

- ↑ Wang, K. K.; Sampliner, R. E.; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology (2008). "Updated Guidelines 2008 for the Diagnosis, Surveillance and Therapy of Barrett's Esophagus". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 103 (3): 788–797. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01835.x. PMID 18341497.

- ↑ Winawer, S.; Fletcher, R.; Rex, D.; Bond, J.; Burt, R.; Ferrucci, J.; Ganiats, T.; Levin, T.; Woolf, S.; Johnson, D.; Kirk, L.; Litin, S.; Simmang, C.; Gastrointestinal Consortium, P. (2003). "Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: Clinical guidelines and rationale—Update based on new evidence". Gastroenterology. 124 (2): 544–560. doi:10.1053/gast.2003.50044. PMID 12557158.

- ↑ Jarbol, D. E.; Kragstrup, J.; Stovring, H.; Havelund, T.; Schaffalitzky De Muckadell, O. B.; Deal, S. E.; Hoffman, B.; Jacobson, B. C.; Mergener, K.; Petersen, B. T.; Safdi, M. A.; Faigel, D. O.; Pike, I. M.; ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy (2006). "Proton Pump Inhibitor or Testing for Helicobacter pylori as the First Step for Patients Presenting with Dyspepsia? A Cluster-Randomized Trial". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 101 (6): 1200–1208. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00673.x. PMID 16635231.

- ↑ Levin, B.; Lieberman, D. A.; McFarland, B.; Andrews, K. S.; Brooks, D.; Bond, J.; Dash, C.; Giardiello, F. M.; Glick, S.; Johnson, D.; Johnson, C. D.; Levin, T. R.; Pickhardt, P. J.; Rex, D. K.; Smith, R. A.; Thorson, A.; Winawer, S. J.; American Cancer Society Colorectal Cancer Advisory Group; Us Multi-Society Task, F.; American College of Radiology Colon Cancer Committee (2008). "Screening and Surveillance for the Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer and Adenomatous Polyps, 2008: A Joint Guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology". Gastroenterology. 134 (5): 1570–1595. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. PMID 18384785.

- ↑ "Definition: hyperchromatic from Online Medical Dictionary". Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ↑ Abrams, Gerald. "Neoplasia I". Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ↑ Ridge JA, Glisson BS, Lango MN, et al. "Head and Neck Tumors" in Pazdur R, Wagman LD, Camphausen KA, Hoskins WJ (eds.) Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 11th ed. 2008.

References

- Noel Weidner (editor), Richard Cote, Saul Suster, Lawrence Weiss (2003). Modern Surgical Pathology. London: W.B. Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-7253-1. OCLC 50244347.

- Ramzi S. Cotran, Vinay Kumar, Tucker Collins (Editor) (1999). Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease (6th ed.). London: W.B. Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-7335-X. OCLC 39465455.