Dromomeron

| Dromomeron Temporal range: Late Triassic, 220–211.9 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

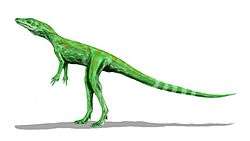

| Hypothetical reconstruction of Dromomeron romeri | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauromorpha |

| Family: | †Lagerpetidae |

| Genus: | †Dromomeron Irmis et al., 2007 |

| Species | |

Dromomeron (meaning "running femur") is a genus of lagerpetonid dinosauromorph archosaur that lived around 220 to 211.9 ± 0.7 million years ago.[1] The genus containing species known from Late Triassic-age rocks of the southwestern United States and northwestern Argentina. It is described as most closely related to the earlier Lagerpeton of Argentina, but was found among remains of true dinosaurs like Chindesaurus, indicating that the first dinosaurs did not immediately replace related groups.[2]

Based on the study of the overlapping material of Dromomeron and Tawa hallae, Christopher Bennett proposed that the two taxa were conspecific, forming a single growth series of Dromomeron.[3]

Description

It is known from partial remains, largely from the hindlimbs,[2][4] which indicate an animal with an overall length of 1 meters (3.3 ft).[5]

Classification

The bones of Dromomeron are most similar to those of the older dinosauromorph Lagerpeton,[2] and the two animals have been classified together in a clade Lagerpetonidae.[4]

Cladogram simplified after Kammerer, Nesbitt & Shubin (2012):[6]

| Ornithodira |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Discovery and species

Dromomeron romeri

The species name romeri honors influential 20th-century vertebrate paleontologist Alfred Sherwood Romer.[2] Dromomeron and type species D. romeri is based on GR 218, a complete left thigh bone from the Hayden Quarry at Ghost Ranch, New Mexico. The rocks there are in the lower portion of the Petrified Forest Member of the Chinle Formation, and are Norian in age. Additional hindlimb bones, some probably from the same individual, are also known,[2] and a partial skeleton has been recovered from Hayden Quarry, but has not yet been fully prepared. A few other specimens have been recovered from nearby localities, including the Snyder Quarry.[4] Other specimens from the Chinle Formation of Arizona and a roughly contemporaneous part of the Dockum Group of Texas also have been assigned to this genus.[7] These have been assigned to second species D. gregorii, named in 2009.[4]

Dromomeron gregorii

D. gregorii, named for Joseph T. Gregory, is based on TMM 31100–1306, a right femur (thigh bone) from the Otis Chalk Quarry, Colorado City Formation, (Dockum Group), near Otis Chalk, Texas. Several other limb bones from the quarry, and a partial femur (thigh bone) from the Placerias Quarry of eastern Arizona have been assigned to this species. The rocks that D. gregorii is known from are older than those romeri has been found in. As with the Hayden Quarry, the Otis Chalk Quarry has at least one specimen of a herrerasaurid.[4]

Dromomeron gigas

A third species, D. gigas, was described by Martínez et al. (2016) on the basis of fossils recovered from the Norian Quebrada del Barro Formation in northwestern Argentina.[8]

Paleoecology

Also found at the Hayden Quarry are the remains of phytosaurs, aetosaurs, rauisuchians, and several types of dinosaurs and dinosaur relatives, including a Silesaurus-like animal, the herrerasaurid Chindesaurus, and the basal theropod Tawa. Finding the remains of four types of dinosaurs and dinosaur relatives (including Dromomeron itself) is noteworthy because it shows that dinosaurs did not immediately replace their dinosauromorph predecessors; that some of these groups, like the lagerpetonids, persisted (for longer than previously known) and diversified; and that dinosaurian replacement may have occurred at different times in different areas.[2]

References

- ↑ Sterling J. Nesbitt; Julia Brenda Desojo; Randall B. Irmis, eds. (2013). Anatomy, Phylogeny and Palaeobiology of Early Archosaurs and Their Kin. The Geological Society of London. p. 164. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Irmis, Randall B.; Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Padian, Kevin; Smith, Nathan D.; Turner, Alan H.; Woody, Daniel; Downs, Alex (2007). "A Late Triassic dinosauromorph assemblage from New Mexico and the rise of dinosaurs". Science. 317 (5836): 358–361. doi:10.1126/science.1143325. PMID 17641198.

- ↑ Bennett, C.S. (2013). "A Rebuttal to Nesbitt's and Hone's "An external mandibular fenestra and other archosauriform characteristics in basal pterosaurs"" (PDF). International Symposium on Pterosaurs: 19–22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Irmis, Randall B.; Parker, William G.; Smith, Nathan D.; Turner, Alan H.; Rowe, Timothy (2009). "Hindlimb osteology and distribution of basal dinosauromorphs from the Late Triassic of North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (2): 498–516. doi:10.1671/039.029.0218.

- ↑ Estimate after the scale diagram at the article's press fact sheet.

- ↑ Kammerer, C. F.; Nesbitt, S. J.; Shubin, N. H. (2012). "The First Silesaurid Dinosauriform from the Late Triassic of Morocco". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 57 (2): 277. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0015.

- ↑ Irmis, Randall B.; Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Padian, Kevin; Smith, Nathan D.; Turner, Alan H.; Woody, Daniel; Downs, Alex (2007). "Supporting online material for A Late Triassic dinosauromorph assemblage from New Mexico and the rise of dinosaurs" (PDF). Science. doi:10.1126/science.1143325. Retrieved 2007-07-22.

- ↑ Ricardo N. Martínez; Cecilia Apaldetti; Gustavo A. Correa; Diego Abelín (2016). "A Norian lagerpetid dinosauromorph from the Quebrada del Barro Formation, northwestern Argentina". Ameghiniana. 53 (1): 1–13. doi:10.5710/AMGH.21.06.2015.2894.

External links

- Online supplementary material for the Irmis et al.. article (PDF).

- A fact sheet for the Irmis et al.. article.