Dravidian languages

| Dravidian | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: | South Asia, mostly South India and northern Sri Lanka | ||

| Linguistic classification: | One of the world's primary language families | ||

| Proto-language: | Proto-Dravidian | ||

| Subdivisions: |

| ||

| ISO 639-2 / 5: | dra | ||

| Linguasphere: | 49= (phylozone) | ||

| Glottolog: | drav1251[1] | ||

|

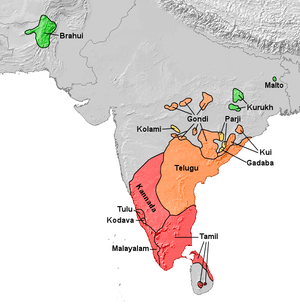

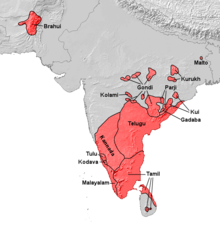

Distribution of subgroups of Dravidian languages:

| |||

| Part of a series on |

| Dravidian culture and history |

|---|

|

|

History |

|

Regions

|

|

People |

| Portal:Dravidian civilizations |

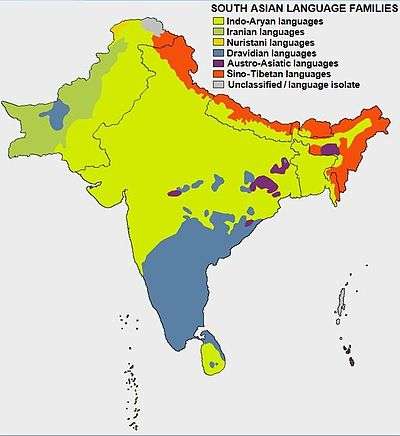

The Dravidian languages are a language family spoken mainly in southern India and parts of eastern and central India, as well as in northeastern Sri Lanka with small pockets in southwestern Pakistan, southern Afghanistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and Bhutan,[2] and overseas in other countries such as Malaysia and Singapore. The Dravidian languages with the most speakers are Telugu, Tamil, Kannada and Malayalam. There are also small groups of Dravidian-speaking scheduled tribes, who live beyond the mainstream communities, such as the Kurukh and Gond tribes.[3]

Though some argue that the Dravidian languages may have been brought to India by migrations in the fourth or third millennium BCE[4][5][6] or even earlier,[7] the Dravidian languages cannot easily be connected to any other language, and they could well be indigenous to India.[8]

Epigraphically the Dravidian languages have been attested since the 2nd century BCE. Only two Dravidian languages are exclusively spoken outside India: Brahui in Pakistan and Dhangar, a dialect of Kurukh, in Nepal. Dravidian place names along the Arabian Sea coast and the Dravidian grammatical influence such as clusivity in the Indo-Aryan languages, namely Marathi, Konkani, Gujarati, Marwari, and Sindhi, suggest that Dravidian languages were once spoken more widely across the Indian subcontinent.[9][10]

Etymology

Alexander D. Campbell first suggested the existence of a Dravidian language family in 1816 in his Grammar of the Teloogoo Language,[11] in which he and Francis W. Ellis argued that Tamil and Telugu descended from a common, non-Indo-European ancestor.[12] In 1856 Robert Caldwell published his Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian Family of Languages,[13] which considerably expanded the Dravidian umbrella and established Dravidian as one of the major language groups of the world. Caldwell coined the term "Dravidian" for this family of languages, based on the usage of the Sanskrit word drāviḍa in the work Tantravārttika by Kumārila Bhaṭṭa.[14] In his own words, Caldwell says,

The word I have chosen is 'Dravidian', from Drāviḍa, the adjectival form of Draviḍa. This term, it is true, has sometimes been used, and is still sometimes used, in almost as restricted a sense as that of Tamil itself, so that though on the whole it is the best term I can find, I admit it is not perfectly free from ambiguity. It is a term which has already been used more or less distinctively by Sanskrit philologists, as a generic appellation for the South Indian people and their languages, and it is the only single term they ever seem to have used in this manner. I have, therefore, no doubt of the propriety of adopting it.[15]

The 1961 publication of the Dravidian etymological dictionary by T. Burrow and M. B. Emeneau proved a notable event in the study of Dravidian linguistics.

As for the origin of the Sanskrit word drāviḍa itself, researchers have proposed various theories. Basically the theories deal with the direction of derivation between tamiẓ and drāviḍa. There is no definite philological and linguistic basis for asserting unilaterally that the name Dravida also forms the origin of the word Tamil (Dravida → Dramila → Tamizha or Tamil). Kamil Zvelebil cites the forms such as dramila (in Daṇḍin's Sanskrit work Avanisundarīkathā) damiḷa (found in the Sri Lankan (Ceylonese) chronicle Mahavamsa) and then goes on to say, "The forms damiḷa/damila almost certainly provide a connection of dr(a/ā)viḍa " and "... tamiḷ < tamiẓ ...whereby the further development might have been *tamiẓ > *damiḷ > damiḷa- / damila- and further, with the intrusive, 'hypercorrect' (or perhaps analogical) -r-, into dr(a/ā)viḍa. The -m-/-v- alternation is a common enough phenomenon in Dravidian phonology"[16] Zvelebil in his earlier treatise states, "It is obvious that the Sanskrit dr(a/ā)viḍa, Pali damila, damiḷo and Prakrit d(a/ā)viḍa are all etymologically connected with tamiẓ", and further remarks, "The r in tamiẓ → dr(a/ā)viḍa is a hypercorrect insertion, cf. an analogical case of DED 1033 Ta. kamuku, Tu. kangu "areca nut": Skt. kramu(ka)."[17]

Further, another Dravidian linguist, Bhadriraju Krishnamurti, in his book Dravidian Languages states,[18]

Joseph (1989: IJDL 18.2:134-42) gives extensive references to the use of the term draviḍa, dramila first as the name of a people, then of a country. Sinhala BCE inscriptions cite dameḍa-, damela- denoting Tamil merchants. Early Buddhist and Jaina sources used damiḷa- to refer to a people of south India (presumably Tamil); damilaraṭṭha- was a southern non-Aryan country; dramiḷa-, dramiḍa, and draviḍa- were used as variants to designate a country in the south (Bṛhatsamhita-, Kādambarī, Daśakumāracarita-, fourth to seventh centuries CE) (1989: 134–138). It appears that damiḷa- was older than draviḍa- which could be its Sanskritization.

Based on what Krishnamurti states (referring to a scholarly paper published in the International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics), the Sanskrit word draviḍa itself is later than damiḷa since the dates for the forms with -r- are centuries later than the dates for the forms without -r- (damiḷa, dameḍa-, damela- etc.). The Monier-Williams Sanskrit Dictionary lists for the Sanskrit word draviḍa a meaning of "collective Name for 5 peoples, viz. the Āndhras, Karṇāṭakas, Gurjaras, Tailaṅgas, and Mahārāṣṭras".[19]

Classification

The Dravidian languages form a close-knit family. They are descended from the Proto-Dravidian language. There is reasonable agreement on how they are related to each other. Most scholars agree on four groups: North, Central (Kolami–Parji), South-Central (Telugu–Kui) and South Dravidian. Earlier classifications grouped Central and South-Central Dravidian in a single branch. The classification below follows Krishnamurti in grouping South-Central and South Dravidian.[20] Languages recognized as official languages of India appear here in boldface.

| Dravidian |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

In addition, Ethnologue lists several unclassified Dravidian languages: Allar, Bazigar, Bharia, Malankuravan (possibly a dialect of Malayalam), Vishavan, as well as the otherwise unclassified Southern Dravidian languages Mala Malasar, Malasar, Thachanadan, Ullatan, Kalanadi, Kumbaran, Kunduvadi, Kurichiya, Attapady Kurumba, Muduga, Pathiya and Wayanad Chetti to Tamil-Kannada.

North Dravidian

Some authors deny that North Dravidian forms a valid subgroup, splitting it into Northeast (Kurukh–Malto) and Northwest (Brahui).[21] Their affiliation has been proposed primarily based on a small number of common phonetic developments, including:

- In some words, *k is retracted or spirantized, shifting to /x/ in Kurukh and Brahui, /q/ in Malto.

- In some words, *c is retracted to /k/.

- Word-initial *v develops to /b/. This development is however also found in several other Dravidian languages, including Kannada, Kodagu and Tulu.

McAlpin (2003)[22] notes that no exact conditioning can be established for the first two changes, and proposes that distinct Proto-Dravidian *q and *kʲ should be reconstructed behind these correspondences; and that Brahui, Kurukh-Malto and the rest of Dravidian may be three coordinate branches, possibly with Brahui being the earliest language to split off. A few morphological parallels between Brahui and Kurukh-Malto are also known, but according to McAlpin they are analyzable as shared archaisms rather than shared innovations.

Distribution

Approximately 29% of India's population spoke Dravidian languages in 1981.[23] The proportion has fallen due to lower birth rates compared to the Indo-Aryan speakers and according to 2001 census, about 21.5% or 220 million of total population of 1.02 billion were Dravidian speakers.[24]

Proposed relations with other families

The Dravidian family has defied all of the attempts to show a connection with other languages, including Indo-European, Hurrian, Basque, Sumerian, and Korean. Comparisons have been made not just with the other language families of the Indian subcontinent (Indo-European, Austroasiatic, Sino-Tibetan, and Nihali), but with all typologically similar language families of the Old World. Nonetheless, although there are no readily detectable genealogical connections, Dravidian shares strong areal features with the Indo-Aryan languages, which have been attributed to a substratum influence from Dravidian.[25]

Dravidian languages display typological similarities with the Uralic language group, suggesting to some a prolonged period of contact in the past.[26] This idea is popular amongst Dravidian linguists and has been supported by a number of scholars, including Robert Caldwell,[27] Thomas Burrow,[28] Kamil Zvelebil,[29] and Mikhail Andronov.[30] This hyphothesis has, however, been rejected by some specialists in Uralic languages,[31] and has in recent times also been criticised by other Dravidian linguists such as Bhadriraju Krishnamurti.[32]

Dravidian is one of the primary language families in the Nostratic proposal, which would link most languages in North Africa, Europe and Western Asia into a family with its origins in the Fertile Crescent sometime between the last Ice Age and the emergence of proto-Indo-European 4–6 thousand years BCE. However, the general consensus is that such deep connections are not, or not yet, demonstrable. McAlpin (1975) proposed linking Dravidian languages with the ancient Elamite language of what is now southwestern Iran. However, despite decades of research, this Elamo-Dravidian language family has not been demonstrated to the satisfaction of other historical linguists.

Literature

Four Dravidian languages, Tamil, Kannada, Malayalam and Telugu, have lengthy literary traditions.[33] Literature in Tulu and Kodava is more recent.[33]

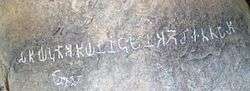

The earliest known Dravidian inscriptions are 76 Old Tamil inscriptions on cave walls in Madurai and Tirunelveli districts in Tamil Nadu, dating from the 2nd century BCE.[34] These inscriptions are written in a variant of the Brahmi script called Tamil Brahmi.[35] The earliest long text in Old Tamil is the Tolkāppiyam, an early work on Tamil grammar and poetics, whose oldest layers could date from the 1st century BCE.[34]

Prehistory

The origins of the Dravidian languages, as well as their subsequent development and the period of their differentiation are unclear, partially due to the lack of comparative linguistic research into the Dravidian languages.

Origins

Indigenous Dravidian language

According to Avari, the Dravidian languages are believed to be indigenous to India.[8]

Dravidian migrations

Reich et al. (2009) discerned two major ancestral components in India,[36][37][38] namely the Ancestral North Indians (ANI) which is "genetically close to Middle Easterners, Central Asians, and Europeans", and the Ancestral South Indians, (ASI) which is clearly distinct from ANI.[36] These two groups mixed in India between 4,200 and 1,900 years ago (2200 BCE–100 CE), whereafter a shift to endogamy took place,[38] possibly by the enforcement of "social values and norms" by the "Hindu Gupta rulers."[39] Moorjani et al. (2013) describe three scenarios regarding the bringing together of the two groups: migrations before the development of agriculture (8,000–9,000 years before present (BP); migration of western Asian people together with the spread of agriculture, maybe up to 4,600 years BP; migrations of western Eurasians from 3,000 to 4,000 years BP.[40] According to Metspalu, the ANI diverged from the present populations of West Eurasia 12,500 years ago.[41] while according to Moorjani et al. (2013) these groups were plausibly present "unmixed" in India before 2,200 BC.[38]

According to David McAlpin, the Dravidian languages were brought to India by immigration into India from Elam, located in present-day southwestern Iran..[5][42] According to Renfrew and Cavalli-Sforza, Proto-Dravidian was brought to India by farmers from the Iranian part of the Fertile Crescent.[43][4][44][note 1] According to Mikhail Andronov, Dravidian languages were brought to India at the beginning of the third millennium BCE.[6]

Kivisild et al. (1999) note that "a small fraction of the 'Caucasoid-specific' mtDNA lineages found in Indian populations can be ascribed to a relatively recent admixture."[45] at ca. 9,300 ± 3,000 years before present,[46] which coincides with "the arrival to India of cereals domesticated in the fertile Crescent" and "lends credence to the suggested linguistic connection between Elamite and Dravidic populations".[46]

According to Gallego Romero et al. (2011), their research on lactose tolerance in India suggests that "the west Eurasian genetic contribution identified by Reich et al. (2009) principally reflects gene flow from Iran and the Middle East."[47] Gallego Romero notes that Indians who are lactose-tolerant show a genetic pattern regarding this tolerance which is "characteristic of the common European mutation."[48] According to Romero, this suggests that "the most common lactose tolerance mutation made a two-way migration out of the Middle East less than 10,000 years ago. While the mutation spread across Europe, another explorer must have brought the mutation eastward to India – likely traveling along the coast of the Persian Gulf where other pockets of the same mutation have been found."[48]

According to Palanichamy et al. (2015), "The presence of mtDNA haplogroups (HV14 and U1a) and Y-chromosome haplogroup (L1) in Dravidian populations indicates the spread of the Dravidian language into India from west Asia."[49]

Differentiation

Proto-Dravidian is thought to have differentiated into Proto-North Dravidian, Proto-Central Dravidian, Proto South-Central Dravidian and Proto-South Dravidian around 500 BC, although some linguists have argued that the degree of differentiation between the sub-families points to an earlier split.

Indo-Aryan migrations and Sanskritization

Northern Dravidian pockets

Although in modern times speakers of the various Dravidian languages have mainly occupied the southern portion of India, in earlier times they probably were spoken in a larger area. After the arrival of the Indo-Aryans, a process of Sanskritization started which led to a language shift in northern India.[44] Southern India has remained majority Dravidian, but pockets of Dravidian can be found in central India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal.

The Kurukh and Malto are pockets of Dravidian languages in central India, who may have migrated from south India. They do have myths about external origins.[50] The Kurukh have traditionally claimed to be from the Deccan Peninsula,[51] more specifically Karnataka. The same tradition has existed of the Brahui,[52][53] who call themselves immigrants.[54] Many scholars hold this same view of the Brahui[55] such as L. H. Horace Perera and M. Ratnasabapathy.[56]

The Brahui population of Balochistan has been taken by some as the linguistic equivalent of a relict population, perhaps indicating that Dravidian languages were formerly much more widespread and were supplanted by the incoming Indo-Aryan languages.[57][58][59] However it has been argued that the absence of any Old Iranian (Avestan) loanwords in Brahui suggests that the Brahui migrated to Balochistan from central India less than 1000 years ago. The main Iranian contributor to Brahui vocabulary, Balochi, is a western Iranian language like Kurdish, and arrived in the area from the west only around 1000 AD.[60] Sound changes shared with Kurukh and Malto also suggest that Brahui was originally spoken near them in central India.[61]

Dravidian influence on Sanskrit

According to Asko Parpola, the Harappan civilisation was Dravidian.[62] It influenced the language of the migrating Indo-Aryans.

Dravidian languages show extensive lexical (vocabulary) borrowing, but only a few traits of structural (either phonological or grammatical) borrowing from Indo-Aryan, whereas Indo-Aryan shows more structural than lexical borrowings from the Dravidian languages.[63] Many of these features are already present in the oldest known Indo-Aryan language, the language of the Rigveda (c. 1500 BCE), which also includes over a dozen words borrowed from Dravidian.[64]

Vedic Sanskrit has retroflex consonants (ṭ/ḍ, ṇ) with about 88 words in the Rigveda having unconditioned retroflexes.[65][66] Some sample words are Iṭanta, Kaṇva, śakaṭī, kevaṭa, puṇya and maṇḍūka. Since other Indo-European languages, including other Indo-Iranian languages, lack retroflex consonants, their presence in Indo-Aryan is often cited as evidence of substrate influence from close contact of the Vedic speakers with speakers of a foreign language family rich in retroflex consonants.[65][66] The Dravidian family is a serious candidate since it is rich in retroflex phonemes reconstructible back to the Proto-Dravidian stage.[67][68][69]

In addition, a number of grammatical features of Vedic Sanskrit not found in its sister Avestan language appear to have been borrowed from Dravidian languages. These include the gerund, which has the same function as in Dravidian, and the quotative marker iti.[70] Some linguists explain this asymmetrical borrowing by arguing that Middle Indo-Aryan languages were built on a Dravidian substratum.[71] These scholars argue that the most plausible explanation for the presence of Dravidian structural features in Indic is language shift, that is, native Dravidian speakers learning and adopting Indic languages.[72] Although each of the innovative traits in Indic could be accounted for by internal explanations, early Dravidian influence is the only explanation that can account for all of the innovations at once; moreover, it accounts for several of the innovative traits in Indic better than any internal explanation that has been proposed.[73]

Grammar

The most characteristic grammatical features of Dravidian languages are:[29]

- Dravidian languages are agglutinative.

- Word order is subject–object–verb (SOV).

- Dravidian languages have a clusivity distinction.

- The major word classes are nouns (substantives, numerals, pronouns), adjectives, verbs, and indeclinables (particles, enclitics, adverbs, interjections, onomatopoetic words, echo words).

- Proto-Dravidian used only suffixes, never prefixes or infixes, in the construction of inflected forms. Hence, the roots of words always occurred at the beginning. Nouns, verbs, and indeclinable words constituted the original word classes.

- There are two numbers and four different gender systems, the ancestral system probably having "male:non-male" in the singular and "person:non-person" in the plural.

- In a sentence, however complex, only one finite verb occurs, normally at the end, preceded if necessary by a number of gerunds.

- Word order follows certain basic rules but is relatively free.

- The main (and probably original) dichotomy in tense is past:non-past. Present tense developed later and independently in each language or subgroup.

- Verbs are intransitive, transitive, and causative; there are also active and passive forms.

- All of the positive verb forms have their corresponding negative counterparts, negative verbs.

Phonology

Dravidian languages are noted for the lack of distinction between aspirated and unaspirated stops. While some Dravidian languages have accepted large numbers of loan words from Sanskrit and other Indo-Iranian languages in addition to their already vast vocabulary, in which the orthography shows distinctions in voice and aspiration, the words are pronounced in Dravidian according to different rules of phonology and phonotactics: aspiration of plosives is generally absent, regardless of the spelling of the word. This is not a universal phenomenon and is generally avoided in formal or careful speech, especially when reciting. For instance, Tamil does not distinguish between voiced and voiceless stops. In fact, the Tamil alphabet lacks symbols for voiced and aspirated stops. Dravidian languages are also characterized by a three-way distinction between dental, alveolar, and retroflex places of articulation as well as large numbers of liquids.

Proto-Dravidian

Proto-Dravidian had five short and long vowels: *a, *ā, *i, *ī, *u, *ū, *e, *ē, *o, *ō. There were no diphthongs; ai and au are treated as *ay and *av (or *aw).[74][68][75] The five-vowel system is largely preserved in the descendent subgroups.[76]

The following consonantal phonemes are reconstructed:[67][68][77]

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | *p | *t | *ṯ | *ṭ | *c | *k | |

| Nasals | *m | *n | *ṉ (??) | *ṇ | *ñ | ||

| Fricatives | (*H) | ||||||

| Flap/Rhotics | *r | *ẓ (ḻ, r̤) | |||||

| Lateral | *l | *ḷ | |||||

| Glides | *w [v] | *y |

Numerals

The numerals from 1 to 10 in various Dravidian and Indo-Aryan languages (here exemplified by Hindi, Sanskrit and Marathi).[78]

| Number | Southern | South-Central | Central | Northern | Proto-Dravidian | Indo-Aryan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tamil | Malayalam | Kodava | Tulu | Kannada | Telugu | Kolami | Kurukh | Brahui | Hindi | Sanskrit | Marathi | ||

| 1 | oṉṟu | onnu | ond | onji | ondu | okaṭi | okkod | oṇṭa | asiṭ | *onṯu 1 | ek | éka | ek |

| 2 | iraṇṭu | raṇḍu | danḍ | raḍḍ | eraḍu | renḍu | irāṭ | indiŋ | irāṭ | *iraṇṭu 2 | do | dvi | don |

| 3 | mūṉṟu | mūnnu | mūṉd | mūji | mūṟu | mūḍu | mūndiŋ | mūnd | musiṭ | *muH- | teen | tri | teen |

| 4 | nāṉku | nālu | nāl | nāl | nālku | nālugu | nāliŋ | nāx | čār (II) | *nāl | char | chatúr | chār |

| 5 | aintu | añcu | añji | ayN | aidu | ayidu | ayd 3 | pancē (II) | panč (II) | *cay-m- | panch | pañcha | pātc |

| 6 | āru | āṟu | ār | āji | āṟu | āṟu | ār 3 | soyyē (II) | šaš (II) | *cāṯu | che | ṣáṣ | sahā |

| 7 | ēẓu | ēẓu | ēḻ | yēl | ēlu | ēḍu | ēḍ 3 | sattē (II) | haft (II) | *ēẓ | sat | saptá | sāt |

| 8 | eṭṭu | eṭṭu | eṭṭ | enma | eṇṭu | enimidi | enumadī 3 | aṭṭhē (II) | hašt (II) | *eṇṭṭu | āṭh | aṣṭá | āṭh |

| 9 | oṉpatu 5 | ompatu 5 | oiymbad | ormba | ombattu | tommidi | tomdī 3 | naiṃyē (II) | nōh (II) | *toḷ/*toṇ | nau | náva | nau |

| 10 | pattu | pattu | patt | patt | hattu | padi | padī 3 | dassē (II) | dah (II) | *paH(tu) | das | dáśa | dahā |

- This is the same as the word for another form of the number one in Tamil and Malayalam, used as the indefinite article ("a") and when the number is an attribute preceding a noun (as in "one person"), as opposed to when it is a noun (as in "How many are there?" "One").

- The stem *īr is still found in compound words, and has taken on a meaning of "double" in Tamil, Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam. For example, irupatu (20, literally meaning "double-ten"), iravai (20 in Telugu), "iraṭṭi" ("double") or iruvar ("two people", in Tamil).

- The Kolami numbers 5 to 10 are borrowed from Telugu.

- The word tondu was also used to refer to the number nine in ancient sangam texts but was later completely replaced by the word onpadu.

- These forms are derived from "one (less than) ten". Proto-Dravidian *toḷ is still used in Tamil and Malayalam as the basis of numbers such as 90, thonnooru.

- Words indicated (II) are borrowings from Indo-Iranian languages (in Brahui's case, from Persian).

See also

Notes

- ↑ Derenko: "The spread of these new technologies has been associated with the dispersal of Dravidian and Indo-European languages in southern Asia. It is hypothesized that the proto-Elamo-Dravidian language, most likely originated in the Elam province in southwestern Iran, spread eastwards with the movement of farmers to the Indus Valley and the Indian sub-continent."[44]

Derenko refers to:

* Renfrew (1987), Archaeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins

* Renfrew (1996), Language families and the spread of farming. In: Harris DR, editor, The origins and spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia, pp. 70–92

* Cavalli-Sforza, Menozzi, Piazza (1994), The History and Geography of Human Genes.

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Dravidian". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ https://books.google.com.au/books?id=aUDAAAAAQBAJ&pg=PT72&lpg=PT72&dq=kurukh+people+bhutan+dravidian&source=bl&ots=MnYBtruTVA&sig=4sFJtn9Pte5RO6RNYUb9Er5bkJ8&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjz8sPR8-LKAhVBjpQKHWxTA-YQ6AEINjAF#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ West, Barbara A. (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 713. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- 1 2 Namita Mukherjee; Almut Nebel; Ariella Oppenheim; Partha P. Majumder (December 2001), "High-resolution analysis of Y-chromosomal polymorphisms reveals signatures of population movements from central Asia and West Asia into India" (PDF), Journal of Genetics, Springer India, 80 (3): 125–35, doi:10.1007/BF02717908, PMID 11988631, retrieved 2008-11-25,

... More recently, about 15,000–10,000 years before present (ybp), when agriculture developed in the Fertile Crescent region that extends from Israel through northern Syria to western Iran, there was another eastward wave of human migration (Cavalli-Sforza et al., 1994; Renfrew 1987), a part of which also appears to have entered India. This wave has been postulated to have brought the Dravidian languages into India (Renfrew 1987). Subsequently, the Indo-European (Aryan) language family was introduced into India about 4,000 ybp ...

- 1 2 Dhavendra Kumar (2004), Genetic Disorders of the Indian Subcontinent, Springer, ISBN 1-4020-1215-2, retrieved 2008-11-25,

... The analysis of two Y chromosome variants, Hgr9 and Hgr3 provides interesting data (Quintan-Murci et al., 2001). Microsatellite variation of Hgr9 among Iranians, Pakistanis and Indians indicate an expansion of populations to around 9000 YBP in Iran and then to 6,000 YBP in India. This migration originated in what was historically termed Elam in south-west Iran to the Indus valley, and may have been associated with the spread of Dravidian languages from south-west Iran (Quintan-Murci et al., 2001). ...

- 1 2 Andronov (2003), p. 299.

- ↑ Tamil Literature Society (1963), Tamil Culture, 10, Academy of Tamil Culture, retrieved 2008-11-25,

... together with the evidence of archaeology would seem to suggest that the original Dravidian-speakers entered India from Iran in the fourth millennium BC ...

- 1 2 Avari (2007).

- ↑ Erdosy (1995), p. 271.

- ↑ Edwin Bryant, Laurie L. Patton (2005), The Indo-Aryan controversy: evidence and inference in Indian history, p. 254

- ↑ Alexander Duncan Campbell (1816) A Grammar of the Teloogoo Language, commonly termed the Gentoo, peculiar to the Hindoos inhabiting the north eastern provinces of the Indian peninsula, College of Fort St. George Press, Madras OCLC 416559272

- ↑ Sreekumar (2009).

- ↑ Robert Caldwell (1856) A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian Family of Languages, Williams and Norgate, London OCLC 20216805

- ↑ Zvelebil (1990), p. xx.

- ↑ Caldwell (1856), p. 4.

- ↑ Zvelebil (1990), p. xxi.

- ↑ Zvelebil (1975), p. 53.

- ↑ Krishnamurti (2003), p. 2, footnote 2.

- ↑ Sanskrit, Tamil and Pahlavi Dictionaries

- ↑ Krishnamurti (2003), p. 21.

- ↑ Ruhlen (1991), pp. 138–141.

- ↑ McAlpin, David W. (2003). "Velars, Uvulars and the Northern Dravidian hypothesis". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 123 (3): 521–546. doi:10.2307/3217749.

- ↑ Ishtiaq, M. (1999). Language Shifts Among the Scheduled Tribes in India: A Geographical Study. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. pp. 26–27. ISBN 9788120816176. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ↑ Comparative Speaker's Strength of Scheduled Languages – 1971, 1981, 1991 and 2001, Census of India, 1991

- ↑ Krishnamurti (2003), pp. 38–42.

- ↑ Tyler, Stephen (1968). "Dravidian and Uralian: the lexical evidence". Language. 44 (4): 798–812. doi:10.2307/411899.

- ↑ Webb, Edward (1860). "Evidences of the Scythian Affinities of the Dravidian Languages, Condensed and Arranged from Rev. R. Caldwell's Comparative Dravidian Grammar". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 7: 271–298. doi:10.2307/592159.

- ↑ Burrow, T (1944). "Dravidian Studies IV: The Body in Dravidian and Uralian". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 11 (2): 328–356. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00072517.

- 1 2 Zvelebil, Kamal (2006). Dravidian Languages. In Encyclopædia Britannica (DVD edition).

- ↑ Andronov, Mikhail S. (1971), "Comparative Studies on the Nature of Dravidian-Uralian Parallels: A Peep into the Prehistory of Language Families". Proceedings of the Second International Conference of Tamil Studies Madras. 267–277.

- ↑ Zvelebil, Kamal (1970), Comparative Dravidian Phonology Mouton, The Hauge. at p. 22 contains a bibliography of articles supporting and opposing the theory

- ↑ Krishnamurti (2003), p. 43.

- 1 2 Krishnamurti (2003), p. 20.

- 1 2 Krishnamurti (2003), p. 22.

- ↑ Mahadevan (2003), pp. 90–95.

- 1 2 Reich et al. (2009).

- ↑ Metspalu et al. (2011).

- 1 2 3 Moorjani et al. (2013).

- ↑ Basu et al. (2016), p. 1598.

- ↑ Moorjani et al. (2013), p. 422–423.

- ↑ Srinath Perur, The origins of Indians. What our genes are telling us., Fountain Ink

- ↑ David McAlpin, "Toward Proto-Elamo-Dravidian", Language vol. 50 no. 1 (1974); David McAlpin: "Elamite and Dravidian, Further Evidence of Relationships", Current Anthropology vol. 16 no. 1 (1975); David McAlpin: "Linguistic prehistory: the Dravidian situation", in Madhav M. Deshpande and Peter Edwin Hook: Aryan and Non-Aryan in India, Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (1979); David McAlpin, "Proto-Elamo-Dravidian: The Evidence and its Implications", Transactions of the American Philosophical Society vol. 71 pt. 3, (1981)

- ↑ Cavalli-Sforza (1994), p. 221-222.

- 1 2 3 Derenko (2013).

- ↑ Kivisild 1999, p. 1331.

- 1 2 Kivisild 1999, p. 1333.

- ↑ Gallego Romero (2011), p. 9.

- 1 2 Rob Mitchum (2011), Lactose Tolerance in the Indian Dairyland, ScienceLife

- ↑ Palanichamy (2015), p. 645.

- ↑ P. 83 The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate By Edwin Bryant

- ↑ P. 18 The Orāons of Chōtā Nāgpur: their history, economic life, and social organization. by Sarat Chandra Roy, Rai Bahadur; Alfred C Haddon

- ↑ P. 12 Origin and Spread of the Tamils By V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar

- ↑ P. 32 Ideology and status of Sanskrit : contributions to the history of the Sanskrit language by Jan E M Houben

- ↑ P. 45 The Brahui language, an old Dravidian language spoken in parts of Baluchistan and Sind by Sir Denys Bray

- ↑ Ancient India; Culture and Thought By M. L. Bhagi

- ↑ P. 23 Ceylon & Indian History from Early Times to 1505 A. D. By L. H. Horace Perera, M. Ratnasabapathy

- ↑ Mallory (1989), p. 44.

- ↑ Elst (1999), p. 146.

- ↑ Trask (2000), p. 97"It is widely suspected that the extinct and undeciphered Indus Valley language was a Dravidian language, but no confirmation is available. The existence of the isolated northern outlier Brahui is consistent with the hypothesis that Dravidian formerly occupied much of North India but was displaced by the invading Indo-Aryan languages, and the presence in the Indo-Aryan languages of certain linguistic features, such as retroflex consonants, is often attributed to Dravidian substrate influence."

- ↑ Elfenbein, Josef (1987). "A periplus of the 'Brahui problem'". Studia Iranica. 16 (2): 215–233. doi:10.2143/SI.16.2.2014604.

- ↑ Krishnamurti (2003), pp. 27, 142.

- ↑ Parpola (2010).

- ↑ "Dravidian languages." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 30 Jun. 2008

- ↑ Krishnamurti (2003), p. 6.

- 1 2 Kuiper (1991).

- 1 2 Witzel (1999).

- 1 2 Subrahmanyam (1983), p. 40.

- 1 2 3 Zvelebil (1990).

- ↑ Krishnamurti (2003), p. 36.

- ↑ Krishnamurti (2003), pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Krishnamurti (2003), pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Erdosy (1995), p. 18.

- ↑ Thomason & Kaufman (1988), pp. 141–144.

- ↑ Subrahmanyam (1983).

- ↑ Krishnamurti (2003), p. 90.

- ↑ Krishnamurti (2003), p. 48.

- ↑ Krishnamurti (2003), p. 91.

- ↑ Krishnamurti (2003), pp. 260–265.

Bibliography

- Andronov, Mikhail Sergeevich (2003). A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Languages. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-04455-4.

- Avari, Burjor (2007), Ancient India: A History of the Indian Sub-Continent from C. 7000 BC to AD 1200, Routledge, ISBN 9781134251629

- Basu, Analabha; Sarkar-Roya, Neeta; Majumder, Partha P. (February 9, 2016), "Genomic reconstruction of the history of extant populations of India reveals five distinct ancestral components and a complex structure", PNAS, 113 (6): 1594–9, Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.1594B, doi:10.1073/pnas.1513197113, PMC 4760789

, PMID 26811443

, PMID 26811443 - Caldwell, Robert (1856), A comparative grammar of the Dravidian, or, South-Indian family of languages, London: Harrison; Reprinted London, K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & co., ltd., 1913; rev. ed. by J.L. Wyatt and T. Ramakrishna Pillai, Madras, University of Madras, 1961, reprint Asian Educational Services, 1998. ISBN 81-206-0117-3

- Campbell, A.D. (1849), A grammar of the Teloogoo language, commonly termed the Gentoo, peculiar to the Hindoos inhabiting the northeastern provinces of the Indian peninsula (3d ed.), Madras: Hindu Press.

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca; Menozzi, Paolo; Piazza, Alberto (1994), The History and Geography of Human Genes, Princeton University Press

- Derenko, Miroslava (2013), "Complete Mitochondrial DNA Diversity in Iranians", PLoS ONE, 8 (11): e80673, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080673, PMC 3828245

, PMID 24244704

, PMID 24244704 - Elst, Koenraad (1999), Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate, New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, ISBN 81-86471-77-4.

- Erdosy, George, ed. (1995), The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: Language, Material Culture and Ethnicity, Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 3-11-014447-6.

- Gallego Romero, Irene; et al. (2011), "Herders of Indian and European Cattle Share their Predominant Allele for Lactase Persistence", Mol. Biol. Evol., 29 (1): 249–60, doi:10.1093/molbev/msr190, PMID 21836184

- Kivisild; et al. (1999), "Deep common ancestry of Indian and western-Eurasian mitochondrial DNA lineages" (PDF), Curr. Biol., 9 (22): 1331–1334, doi:10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80057-3, PMID 10574762

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003), The Dravidian Languages, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-77111-0.

- Kuiper, F.B.J. (1991), Aryans in the Rig Veda, Rodopi, ISBN 90-5183-307-5.

- Mallory, J. P. (1989), In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology and Myth, London: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-05052-1.

- Metspalu, Mait; Romero, Irene Gallego; Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Mallick, Chandana Basu; Hudjashov, Georgi; Nelis, Mari; Mägi, Reedik; Metspalu, Ene; Remm, Maido; Pitchappan, Ramasamy; Singh, Lalji; Thangaraj, Kumarasamy; Villems, Richard; Kivisild, Toomas (2011), "Shared and Unique Components of Human Population Structure and Genome-Wide Signals of Positive Selection in South Asia", The American Journal of Human Genetics, 89 (6): 731–744, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.010, ISSN 0002-9297

- Moorjani, P.; Thangaraj, K.; Patterson, N.; Lipson, M.; Loh, P. R.; Govindaraj, P.; Singh, L. (2013), "Genetic evidence for recent population mixture in India", The American Journal of Human Genetics, 93 (3): 422–438, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.07.006, PMC 3769933

, PMID 23932107

, PMID 23932107 - Palanichamy, Malliya Gounder (2015), "West Eurasian mtDNA lineages in India: an insight into the spread of the Dravidian language and the origins of the caste system", Human Genetics, 134 (6): 637–47, doi:10.1007/s00439-015-1547-4, PMID 25832481

- Parpola, Asko (2010), A Dravidian solution to the Indus script problem (PDF), World Classical Tamil Conference

- Reich, David; Thangaraj, Kumarasamy; Patterson, Nick; Price, Alkes L.; Singh, Lalji (2009), "Reconstructing Indian population history", Nature, 461 (7263): 489–494, Bibcode:2009Natur.461..489R, doi:10.1038/nature08365, ISSN 0028-0836, PMC 2842210

, PMID 19779445

, PMID 19779445 - Ruhlen, Merritt (1991), A Guide to the World's Languages: Classification, Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0-8047-1894-3.

- Sreekumar, P. (2009), "Francis Whyte Ellis and the Beginning of Comparative Dravidian Linguistics", Historiographia Linguistica, 36 (1): 75–95, doi:10.1075/hl.36.1.04sre.

- Subrahmanyam, P.S. (1983), Dravidian Comparative Phonology, Annamalai University.

- Thomason, Sarah Grey; Kaufman, Terrence (1988), Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics, University of California Press (published 1991), ISBN 0-520-07893-4.

- Trask, Robert Lawrence (2000), The Dictionary of Historical and Comparative Linguistics, Routledge, ISBN 1-57958-218-4.

- Witzel, Michael (1999), "Early Sources for South Asian Substrate Languages" (PDF), Mother Tongue (extra number): 1–76.

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1975), Tamil Literature, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-04190-7.

- —— (1990), Dravidian Linguistics: An Introduction, Pondicherry Institute of Linguistics and Culture, ISBN 978-81-8545-201-2.

External links

- Dravidian Etymological Dictionary. The complete Dravidian Etymological Dictionary in a searchable online form.

- Swadesh lists of Dravidian basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)