Dramatistic pentad

The dramatistic pentad forms the core structure of dramatism, a method for examining motivations that the renowned literary critic Kenneth Burke developed. Dramatism recommends the use of a metalinguistic approach to stories about human action that investigates the roles and uses of five rhetorical elements common to all narratives, each of which is related to a question. These five rhetorical elements form the "dramatistic pentad." Burke argues that an evaluation of the relative emphasis that is given to each of the five elements by a human drama enables a determination of the motive for the behaviour of its characters. A character's stress on one element over the others suggests their world view.

Burke introduced the pentad in his 1945 book "A Grammar of Motives". Burke based his pentad on the scholastic hexameter which defines "questions to be answered in the treatment of a topic: Who, what, where, by what means, why, how, when".[1] Burke created the pentad by combining several of the categories in the scholastic hexameter. The result was a pentad that has the five categories of: act, scene, agent, agency, and purpose. Burke states, "The 'who' is obviously covered by agent. Scene covers the 'where' and the 'when'. The 'why' is purpose. 'How' and 'by what means' fall under agency. All that is left to take care of is act in our terms and 'what' in the scholastic formula".[2]

The pentad also closely follows the journalistic 'Five Ws': who, what, when, where, why. 'Who' maps to agent. 'What' maps to action. 'When' and 'Where' map to scene. 'Why' maps to purpose. There is no direct mapping from the Five Ws to the pentads category of agency but Geoff Hart states "Some authorities add a sixth question, “how”, to this list, but “how to” information generally fits under what, where, or when, depending on the nature of the information." [3]

Rhetorical elements of the dramatistic pentad

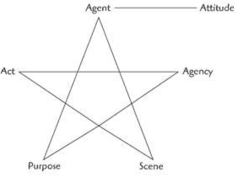

The dramatistic pentad comprises the five rhetorical elements: Act, Scene, Agent, Agency, and Purpose. The “world views” listed below reflect the prominent schools of thought during Burke’s time, “without dismissing any of them," to read them "at once sympathetically and critically in relation to each other," and "in a wider context than any of them recognizes."[4]

Act

Act, which is associated with dramatic action verbs and answers the question "what?", is related to the world view of realism; What happened? What is the action? What is going on? What action; what thoughts? Burke defines the act as that which “names what took place, in thought or deed.” Since an act is likely composed of many separate actions, Burke states that “any verb, no matter how specific or general, that has connotations of consciousness or purpose falls under this category.”[5]

Scene

Scene, which is associated with the setting of an act and answers the questions "when?" and "where?", is related to the world view of materialism and minimal or non-existent free will. Burke defines the scene as “the background of an act, the situation in which it occurred.” [6]

Agent

Agent, which answers the question "by whom?", reflects the world view of philosophical idealism. Burke defines the agent as “what person or kind of person performed the act.” [7]

Agency

Agency (means), which is associated with the person or the organization that committed the deed and answers the question "how?", implies a pragmatic point of view. Burke defines agency as “what instrument or instruments he used.”[8]

Purpose

Purpose, which is associated with meaning and answers the question "why?", indicates that the agent seeks unity through identification with an ultimate meaning of life. Reflects the world view of mysticism. Purpose is inextricably linked to the analysis of “Motive” which, derived from the title of A Grammar of Motives, is the main subject of its analysis. Since Purpose is both the subject of analysis and an element of the dramatistic pentad, it is not a common element to be included in a ratio.

Ratios within the dramatistic pentad

In A Grammar of Motives, Burke provides a system of analysis for the Scene-Act ratio and the Scene-Agent ratio, though his analysis of ratios in the analysis of rhetoric is not limited to these. He states that, “The principles of dramatic consistency would lead one to expect such cases of overlap among the terms; but while being aware of them we should firmly fix in our minds such cases as afford a clear differentiation. Our terms leaning themselves towards merger and division, we are here trying to divide two of them while recognizing their possibilities of merger.” [9] Thus any two dramatistic elements can be analyzed in relation to each other, creating a ratio, and can produce individual, yet separate meanings which are equally valid. However, the rhetor’s selection of elements to compose a ratio should be scrutinized, as it can deflect attention away from or direct attention towards aspects of the rhetor’s desire.

This is what Burke calls the “Ubiquity of the Ratios,” claiming that the composition of ratios “are at the very centre of motivational assumptions,” [10] For example, “The maxim ‘terrain determines tactics’ is a strict localization of the scene-act ratio, with ‘terrain’ as the casuistic equivalent for ‘scene’ in a military calculus of motives, and ‘tactics’ as the corresponding ‘act.’"[11] The analysis of a situation as a multi-faceted occurrence is central to Burke’s concept of ratios. Likewise, the substitution of a dramatistic element with another can change an interpretation of the motive, allowing the analyst to modify the ratio in order to highlight the importance of a specific factor. For example, “the resistance of the Russian armies to the Nazi invasion could be explained ‘scenically’ in terms of the Soviet political and economic structure; or one could use the act-agent ratio, attributing the power and tenacity to ‘Russian’ traits of character. However, in deriving the act from the scene, one would have to credit socialism as a major scenic factor, whereas a derivation of the act from agents would allow for a much more felicitous explanation from the standpoint of capitalist apologists.”[12]

The rhetor-agent also has a significant amount of power in crafting the perception of these ratios to their effect, “If an agent acts in keeping with his nature as an agent (act-agent ratio), he may change the nature of the scene accordingly (scene-act ratio) and thereby establish a state of unity between himself and his world (scene-agent ratio)."[13]

Scene-Act ratio

The scene, or the setting, will contain the act, or the what/actions. The way in which the agent interacts with the scene draws out specific analyses usually related to the atmosphere of the setting. While Burke states that, “It is a principle of drama that the nature of acts and agents should be consistent with the nature of the scene,” some “comic and grotesque works may deliberately set these elements at odds with one another, audiences make allowances for such liberty, which reaffirms the same principle of consistency in its very violation.”[14] This reflects the division of most plays into very literal “acts,” as the agents who construct the scene are very literally “acters” whose work is played against the backdrop of the scene.The actions that a person performs are interpreted through the setting or happenings.[15]

Scene-Agent ratio

A relationship between the agent (person) and the scene (place or setting). A scene can pose restrictions on the agent; in a narrative, the person and place should have some connection.[15]

Act-Agent ratio

While requiring the scene to contain them, the agent does not contain the act. Burke states that, “the agent is an author of his acts,” which can “make him or remake him in accordance with their nature.”[16] This is one of the main principles that separates act and agent, producing a linked cycle which constructs the presentation of the agent’s identity.

A sixth element

In A Grammar of Motives, Burke mentions that attitude is “a state of mind,”[17] remaining exterior from the pentad, as it is often “a preparation for an act, which would make it kind of symbolic act, or incipient act. But in its character as a state of mind that may or may not lead to an act, it is clearly classified under the head of agent.”. Burke also refers to attitude as a variation of agency. [18] Prior to 1969 the term attitude is placed under agency, act or agent and is not considered a sixth element.[19] In 1969, Burke places attitude as a new sixth element, yet he does not refer to the pentad as a hexad.[18] Attitude is defined as "the preparation for an act, which would make it a kind of symbolic act, or incipient act." The attitude, like the agency, would answer the “how?”.[20] There is still some uncertainty over whether attitude is an additional element, and thus makes the dramatistic pentad a hexad, or if it is still a sub-element of the original pentad.[18] While Burke has never directly stated that the pentad is a hexad, he has admitted that the addition of attitude to the pentad is similar to gaining “another soul” or an “extra existence.”[21] Scholars have read this as Burke’s desire not to “dispose of” ambiguity, but rather to “study and clarify the resources of ambiguity.”[18] As a result, many diagrams of the pentad depict attitude as a derivative of agent.

Notes

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth. "A Grammar of Motives". University of California Press, 1969, p. 228

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth. "A Grammar of Motives". University of California Press, 1969, p. 228.

- ↑ "The Five Ws of Online Help". by Geoff Hart, TECHWR-L. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- ↑ Fergusson, Francis (1957). Kenneth Burke's A Grammar of Motives. NY: Doubleday Anchor Books. pp. 193–204.

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth (2001). "A Grammar of Motives". The Rhetorical Tradition: 1298.

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth (2001). "A Grammar of Motives". The Rhetorical Tradition: 1301.

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth (2001). "A Grammar of Motives". The Rhetorical Tradition: 1298.

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth (2001). "A Grammar of Motives". The Rhetorical Tradition: 1298.

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth (2001). "A Grammar of Motives". The Rhetorical Tradition: 1305.

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth (2001). "A Grammar of Motives". The Rhetorical Tradition: 1307.

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth. "A Grammar of Motives". The Rhetorical Tradition: 1308.

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth (2001). "A Grammar of Motives". The Rhetorical Tradition: 1310.

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth (2001). "A Grammar of Motives". The Rhetorical Tradition: 1312.

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth (2001). "A Grammar of Motives". The Rhetorical Tradition: 1302.

- 1 2 Burke,Kenneth."Questions and Answers about the Pentad". National Council of Teachers of English, 1978, p. 332-333.

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth (2001). "A Grammar of Motives". The Rhetorical Tradition: 1309.

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth (2001). "A Grammar of Motives". The Rhetorical Situation: 1302.

- 1 2 3 4 Anderson, F. D., & Althouse, M. T. (2010). “Five Fingers or Six? Pentad or Hexad”. KB Journal, 6(2). Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth. "A Grammar of Motives". University of California Press, 1969, p. 476

- ↑ Burke, Kenneth. (1965). “Permanence and Change”. 1954. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

- ↑ King, Andrew (2001). "Disciplining The Master: Finding the Via Media for Kenneth Burke". American Communication Journal. 4 (2).

- ↑ "The Five Ws of Online Help Systems" by Geoff Hart, TECHWR-L. Retrieved April 30, 2012.