Douglas MacArthur in World War II

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur (January 26, 1880 – April 5, 1964) was an American general and field marshal of the Philippine Army. He was a Chief of Staff of the United States Army during the 1930s and played a prominent role in the Pacific theater during World War II. He received the Medal of Honor for his service in the Philippines Campaign.

MacArthur was recalled to active duty in 1941 as commander of U.S. Army Forces in the Far East. A series of disasters followed, starting with the destruction of his air force on December 8, 1941, and the invasion of the Philippines by the Japanese. MacArthur's forces were soon compelled to withdraw to Bataan, where they held out until May 1942. In March 1942, MacArthur, his family and his staff left Corregidor in PT boats, and escaped to Australia, where MacArthur became Supreme Commander, Southwest Pacific Area. For his defense of the Philippines, MacArthur was awarded the Medal of Honor. After more than two years of fighting in the Pacific, he fulfilled a promise to return to the Philippines. He officially accepted Japan's surrender on September 2, 1945.

Philippines Campaign (1941–42)

On July 26, 1941 Roosevelt federalized the Philippine Army, recalled MacArthur to active duty in the U.S. Army as a two star/major general, and named him commander of U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE). MacArthur was promoted to lieutenant general the following day,[1] and then to general on December 20. At the same time, Sutherland was promoted to major general, while Marshall, Spencer B. Akin, and Hugh John Casey were all promoted to brigadier general.[2] On July 31, 1941 the Philippine Department had 22,000 troops assigned, 12,000 of whom were Philippine Scouts. The main component was the Philippine Division, under the command of Major General Jonathan M. Wainwright.[3] Between July and December 1941 the garrison received 8,500 reinforcements.[4] After years of parsimony, much equipment was shipped. By November, a backlog of 1,100,000 shipping tons of equipment intended for the Philippines had accumulated in U.S. ports and depots awaiting vessels.[5]

At 0330 local time on December 8, 1941, Sutherland learned of the attack on Pearl Harbor and informed MacArthur. At 0530, Chief of Staff of the United States Army General George Marshall ordered MacArthur to execute the existing war plan, Rainbow Five. MacArthur did nothing. When, on three occasions, Gen. Breteron requested permission to attack Japanese bases in Formosa (now called Taiwan), in accordance with prewar intentions, he was refused. At 12:30, the Japanese pilots of the 11th Air Fleet achieved complete tactical surprise when they attacked Clark Field and the nearby fighter base at Iba Field. They destroyed or disabled 18 of Far East Air Force's 35 B-17s, 53 of its 107 P-40s, three P-35s, and more than 25 other aircraft. Substantial damage was done to the bases, and casualties totaled 80 killed and 150 wounded.[6] What was left of the Far East Air Force was all but destroyed over the next few days.[7]

Prewar defense plans assumed the Japanese could not be prevented from landing on Luzon and called for U.S. and Filipino forces to abandon Manila and retreat with their supplies to the Bataan peninsula. MacArthur attempted to slow the Japanese advance with an initial defense against the Japanese landings. However, he reconsidered his confidence in the ability of his Filipino troops when the Japanese landing force made a rapid advance after landing at Lingayen Gulf on December 21.[8] He subsequently ordered a retreat to Bataan.[9] Manila was declared an open city and on December 25 MacArthur moved his headquarters to the island fortress of Corregidor in Manila Bay.[10] A series of air raids by the Japanese destroyed all the exposed structures on the island and USAFFE headquarters was moved into the Malinta Tunnel. Later most of the headquarters moved to Bataan, leaving only the nucleus with MacArthur.[11] The troops on Bataan knew that they had been written off but continued to fight. Some blamed Roosevelt and MacArthur for their predicament. A ballad sung to the tune of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" called him "Dugout Doug."[12] However, most clung to the belief that somehow MacArthur "would reach down and pull something out of his hat."[13]

On January 1, 1942 MacArthur was offered and accepted a payment of $500,000 ($8.1 million in current value) from President Quezon of the Philippines as payment for his pre-war service. MacArthur's staff members also received payments: $75,000 for Sutherland, $45,000 for Richard Marshall, and $20,000 for Huff.[14][15] Eisenhower, after being appointed Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force, was also offered money by Quezon, but declined.[16] These payments were known only to a few in Manila and Washington, including President Roosevelt and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, until they were made public by historian Carol Petillo in 1979. The revelation tarnished MacArthur's reputation.[17]

Escape to Australia and Medal of Honor citation

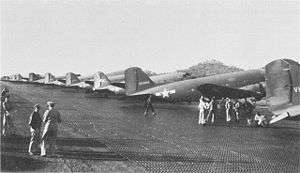

In February 1942, as Japanese forces tightened their grip on the Philippines, MacArthur was ordered by President Roosevelt to relocate to Australia. MacArthur discussed the idea with his staff that he resign his commission and fight on as a private soldier in the Philippine resistance but Sutherland talked him out of it.[18] On the night of March 12, 1942, MacArthur and a select group (that included his wife Jean and son Arthur, as well as Sutherland, Akin, Casey, Marshall, Willoughby, Diller, and George) left Corregidor in four PT boats. MacArthur, his family and Sutherland traveled in PT 41, commanded by Lieutenant John D. Bulkeley. The others followed in PT 34, PT 35 and PT 32. MacArthur and his party reached Del Monte Airfield in Bukidnon province on the island of Mindanao two days later. General George Marshall sent three U.S. Navy B-17s to pick them up. Two of them arrived, and brought the entire group to Australia.[19][20]

MacArthur arrived on March 17 at Batchelor Airfield, about 60 miles (97 km) south of Darwin, before flying to Alice Springs, where he took the Ghan through the Australian outback to Adelaide. His famous speech, in which he said, "I came out of Bataan and I shall return", was first made at Terowie, a small railway township in South Australia on March 20. Upon his arrival in Adelaide, MacArthur abbreviated this to the now-famous, "I came through and I shall return" that made headlines.[21] Washington asked MacArthur to amend his promise to, "We shall return". He ignored the request.[22] Bataan eventually surrendered on April 9,[23] and Wainwright surrendered on Corregidor on May 6.[24]

For his leadership in the defense of the Philippines, General Marshall decided to award MacArthur the Medal of Honor, the decoration for which he had twice previously been nominated. It was admitted that MacArthur had not actually performed acts of valor in battle on Bataan but the 1927 award to Charles Lindbergh set a precedent. MacArthur chose to accept the medal on the basis that "this award was intended not so much for me personally as it is a recognition of the indomitable courage of the gallant army which it was my honor to command."[25] Arthur MacArthur, Jr. and Douglas MacArthur thus became the first father and son to be awarded the Medal of Honor. They remained the only pair until 2001 when Theodore Roosevelt was awarded posthumously for his service during the Spanish–American War, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. having received one posthumously for his service during World War II.[26][27]

New Guinea Campaign

General Headquarters

.jpg)

On April 18, 1942, MacArthur was appointed Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA). Lieutenant General George Brett became Commander, Allied Air Forces, and Vice Admiral Herbert F. Leary became Commander, Allied Naval Forces (though neither of these men were of MacArthur's choosing).[28] Since the bulk of land forces in the theater were Australian, General Marshall insisted an Australian be appointed as Commander, Allied Land Forces, and the job went to General Sir Thomas Blamey. Although predominantly Australian and American, MacArthur's command also included small numbers of personnel from the Netherlands East Indies, the United Kingdom, and other countries.[29] MacArthur established a close relationship with the Prime Minister of Australia, John Curtin,[30] although many Australians resented MacArthur as a foreign general who had been imposed upon them.[31]

The staff of MacArthur's General Headquarters (GHQ) was built around the nucleus that had escaped from the Philippines with him, who became known as the "Bataan Gang".[32] Though Roosevelt and General Marshall pressed for Dutch and Australian officers to be assigned to GHQ, the heads of all the staff divisions were American and such officers of other nationalities as were assigned served under them.[29] Initially located in Melbourne,[33] the GHQ was moved to Brisbane in July because Brisbane was the northernmost city in Australia with the necessary communications facilities.[34] GHQ occupied the AMP Insurance Society building. MacArthur's office and Willoughby's G-2 section were located on the 8th floor, while other staff sections occupied the four floors below.[35]

MacArthur formed his own signals intelligence organization, known as the Central Bureau, from Australian intelligence units and American cryptanalysts who had escaped from the Philippines;[36] this unit forwarded Ultra information to Willoughby for analysis.[37] After a press dispatch revealed details of the Japanese naval concentration at Rabaul during the Battle of the Coral Sea,[38] President Roosevelt ordered that censorship be imposed in Australia. The Advisory War Council subsequently granted censorship authority to the GHQ over the Australian press. Australian newspapers were henceforth restricted to what was reported in the daily GHQ communiqué.[38][39] Veteran correspondents considered them "a total farce" and characterized them as "Alice-in-Wonderland information handed out at high level."[40]

Papuan Campaign

Anticipating that the Japanese would strike at Port Moresby again, the garrison was strengthened and MacArthur ordered the establishment of new bases at Merauke and Milne Bay to cover its flanks.[41] The Battle of Midway in June 1942 led to plans to exploit this victory with a limited offensive in the Pacific. MacArthur's proposal for an attack on the main Japanese base at Rabaul met with objections from the U.S. Navy, which favored a less ambitious approach and objected to an Army general being in command of what would be an amphibious operation. The resulting compromise called for a three-stage advance, with the first, the seizure of the Tulagi area, being conducted by the Pacific Ocean Areas command, under Admiral Chester W. Nimitz. The later stages would be conducted under MacArthur's command as Supreme Allied Commander, South West Pacific Area.[42]

The Japanese struck first, landing at Buna in July,[43] and at Milne Bay in August. The Australians soon defeated the Japanese at Milne Bay,[44] but a series of defeats in the Kokoda Track campaign had a depressing effect back in Australia. On August 30, MacArthur radioed Washington that unless action was taken, the New Guinea Force would be overwhelmed.[45] Having committed all the available Australian troops, MacArthur decided to send American troops. The 32nd Infantry Division, a poorly trained United States National Guard division, was selected to carry out a flanking maneuver.[46] A series of embarrassing American reverses in the Battle of Buna-Gona led to outspoken criticism of the American troops by Blamey and other Australians. MacArthur sent Lieutenant General Robert L. Eichelberger to "take Buna, or not come back alive."[47][48] MacArthur moved the advanced echelon of GHQ to Port Moresby on November 6, 1942.[49] Buna finally fell on January 3, 1943.[50] MacArthur awarded the Distinguished Service Cross to twelve officers for "precise execution of operations." This use of the country's second highest award aroused some resentment, because while some, like Eichelberger and Major General George Alan Vasey, had fought in the field, others, like Sutherland and Willoughby, had not.[51] For his part, MacArthur was awarded his third Distinguished Service Medal,[52] and the Australian government made him an honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath. [53]

MacArthur had little confidence in Brett's abilities as commander of Allied Air Forces SWPA,[28][54][55] and in August 1942 selected Major General George C. Kenney to replace him.[56][57] Kenney's application of air power in support of Blamey's ground forces would soon prove critical to Blamey's victory in the Battle of Wau.[58] In September 1942, Vice Admiral Leary was replaced by Vice Admiral Arthur S. Carpender as commander of Allied Naval Forces SWPA.[59] At that time, MacArthur's naval assets (commonly referred to as MacArthur's Navy) consisted of only 5 cruisers, 8 destroyers, 20 submarines and 7 small craft.[59] This fleet became the Seventh Fleet on 15 March 1943, in advance of Operation Cartwheel.[60]

Operation Cartwheel

At the Pacific Military Conference in March 1943, the Joint Chiefs of Staff approved General MacArthur's plan for Operation Cartwheel, an advance on Rabaul. Owing to a shortage of resources, particularly heavy bomber aircraft, the final stage of the plan, the capture of Rabaul itself, was postponed until 1944.[61] MacArthur explained his strategy:

My strategic conception for the Pacific Theater, which I outlined after the Papuan Campaign and have since consistently advocated, contemplates massive strokes against only main strategic objectives, utilizing surprise and air-ground striking power supported and assisted by the fleet. This is the very opposite of what is termed "island hopping" which is the gradual pushing back of the enemy by direct frontal pressure with the consequent heavy casualties which will certainly be involved. Key points must of course be taken but a wise choice of such will obviate the need for storming the mass of islands now in enemy possession. "Island hopping" with extravagant losses and slow progress...is not my idea of how to end the war as soon and as cheaply as possible. New conditions require for solution and new weapons require for maximum application new and imaginative methods. Wars are never won in the past.[62]

Lieutenant General Walter Krueger's Sixth Army headquarters arrived in SWPA in early 1943 but MacArthur had only three American divisions, and they were tired and depleted from the fighting at Buna and Guadalcanal. As a result, "it became obvious that any military offensive in the South-West Pacific in 1943 would have to be carried out mainly by the Australian Army."[63]

In New Guinea, a country without roads, large-scale transportation of men and material would have to be accomplished by aircraft or ships. A multi-pronged approach was employed to solve this problem. Disassembled landing craft were shipped to Australia, where they were assembled in Cairns.[64] The range of these small landing craft was to be greatly extended by the landing ships of Rear Admiral Daniel E. Barbey's VII Amphibious Force, which began arriving in late 1942.[65] Barbey's force formed part of Carpender's newly formed Seventh Fleet.[59][65] Carpender reported to MacArthur as Supreme Allied Commander, SWPA, but to Admiral Ernest King as Commander Seventh Fleet, which was part of King's United States Fleet.[66] Since the Seventh Fleet had no aircraft carriers, the range of naval operations SWPA was limited by that of the fighter aircraft of the Fifth Air Force. Although a few long-range P-38 Lightning fighters had arrived in SWPA in late 1942, further deliveries were suspended owing to the demands of Operation Torch.[67]

The main offensive began with the landing at Lae by Major General George Wootten's Australian 9th Division and the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade on September 4, 1943. The next day MacArthur watched the landing at Nadzab by paratroops of the 503rd Parachute Infantry from a B-17 circling overhead. The B-17 made the trip on three engines because one failed soon after leaving Port Moresby, but MacArthur insisted that it fly on to Nadzab.[68] For this, MacArthur was awarded the Air Medal.[69]

Vasey's Australian 7th Division and Wooten's 9th Division converged on Lae, which fell on September 16. MacArthur advanced his timetable, and ordered the 7th Division to capture Kaiapit and Dumpu, while the 9th Division mounted an amphibious assault on Finschhafen. Here, the offensive bogged down. Part of the problem was that MacArthur had based his decision to assault Finschhafen on Willoughby's assessment that there were only 350 Japanese defenders at Finschhafen when there were actually nearly 5,000. A furious battle ensued.[70]

In early November, MacArthur's plan for a westward advance along the coast of New Guinea to the Philippines was incorporated into plans for the war against Japan approved at the Cairo Conference.[71][72] Three months later, airmen reported no signs of enemy activity in the Admiralty Islands. Although his intelligence staff did not agree that the islands had been evacuated, MacArthur ordered an amphibious landing on Los Negros Island, marking the beginning of the Admiralty Islands campaign. MacArthur accompanied the assault force aboard USS Phoenix, the flagship of Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, who had recently replaced Carpender as commander of the Seventh Fleet. MacArthur, who came ashore with Kinkaid only seven hours after the first wave of landing craft, was awarded the Bronze Star for his actions in this campaign.[73] After six weeks of fierce fighting, the 1st Cavalry Division captured the islands; the campaign officially ended on 18 May 1944.[74]

MacArthur now bypassed the Japanese forces at Hansa Bay and Wewak, and assaulted Hollandia and Aitape, which Willoughby reported to be lightly defended. Although they were out of range of the Fifth Air Force's fighters based in the Ramu Valley, the timing of the operation allowed the aircraft carriers of the Pacific Fleet to provide air support.[75] Though risky, the operation turned out to be a brilliant success. MacArthur caught the Japanese off balance and cut off Lieutenant General Hatazō Adachi's Japanese XVIII Army in the Wewak area. Because the Japanese were not expecting an attack, the garrison was weak, and Allied casualties were correspondingly light. However, the terrain turned out to be less suitable for airbase development than first thought, forcing MacArthur to seek better locations further west. Moreover, while bypassing Japanese forces had great tactical merit, it had the serious strategic drawback of tying up large numbers of Allied troops in order to contain them, and Adachi was far from beaten. In the Battle of Driniumor River, he would bring on "the New Guinea campaign's bloodiest and most strategically useless battle."[76]

Philippines Campaign (1944–45)

Leyte

In July 1944, President Roosevelt summoned MacArthur to meet with him in Hawaii "to determine the phase of action against Japan." Nimitz and MacArthur agreed that the next step should be to advance on the southern and central Philippines. MacArthur emphasized the moral and political issues involved in a decision to liberate or bypass Luzon. He also spoke briefly of his plan to use the Australian Army to liberate Indonesia. Although the issue was not settled, both Roosevelt and Leahy were convinced of the soundness of MacArthur's plan.[77] In September, Halsey's carriers made a series of air strikes on the Philippines. Opposition was feeble and Halsey concluded that Leyte was "wide open" and possibly undefended, and recommended that projected operations be skipped in favor of an assault on Leyte.[78]

On October 20, 1944, troops of Krueger's Sixth Army landed on Leyte, while MacArthur watched from USS Nashville. That afternoon he arrived off the beach. The advance had not progressed far; snipers were still active and the area was under sporadic mortar fire. When his whaleboat grounded in knee-deep water, MacArthur requested a landing craft, but the beachmaster was too busy to grant his request. MacArthur was compelled to wade ashore.[79][80] In his prepared speech he said:

People of the Philippines: I have returned. By the grace of Almighty God our forces stand again on Philippine soil — soil consecrated in the blood of our two peoples. We have come dedicated and committed to the task of destroying every vestige of enemy control over your daily lives, and of restoring upon a foundation of indestructible strength, the liberties of your people.[81]

Since Leyte was out of range of Kenney's land-based aircraft, MacArthur was entirely dependent on carrier aircraft for cover.[82] Japanese air activity soon increased, with raids on Tacloban, where MacArthur decided to establish his headquarters, and on the fleet offshore. MacArthur enjoyed staying on Nashville's bridge during air raids, although several bombs landed close by, and two nearby cruisers were hit.[83] Over the next few days, the Imperial Japanese Navy staged a major counterattack in the Battle of Leyte Gulf. MacArthur attributed the near-disaster to command being divided between himself and Nimitz.[84] Nor did the campaign ashore proceed smoothly. The timing of the assault so late in the year forced the combat troops, pilots, and the supporting logistical units to contend with heavy monsoonal rains that disrupted the airbase construction program. Adverse weather and valiant Japanese resistance slowed the American advance ashore. MacArthur was forced to ask Nimitz to recall the carriers to support the Sixth Army but they proved to be no substitute for land-based aircraft, and the lack of air cover permitted the Japanese Army to pour troops into Leyte.[85][86] By the end of December, Krueger's headquarters estimated that 5,000 Japanese remained on Leyte, and on December 26 MacArthur issued a communiqué announcing that "the campaign can now be regarded as closed except for minor mopping up." Yet Eichelberger's Eighth Army would kill more than 27,000 Japanese on Leyte between then and the end of the campaign in May 1945.[87] On December 18, 1944, MacArthur was promoted to the new five-star rank of General of the Army — one day before Nimitz was promoted to Fleet Admiral, also a five-star rank.[88] MacArthur had a Filipino silversmith make the rank badges from American, Australian, Dutch and Filipino coins.[89]

Luzon

MacArthur's next move was the invasion of Mindoro, where there were good potential airfield sites around the San Jose area. Willoughby estimated, correctly as it turned out, that the island had only about 1,000 Japanese defenders. The problem this time was getting there. A parachute drop was considered, but the airfields on Leyte lacked the space to hold the required transport aircraft. Kinkaid balked at sending escort carriers into the restricted waters of the Sulu Sea, and Kenney could not guarantee land based air cover. The operation was clearly hazardous, and MacArthur's staff talked him out of accompanying the invasion on the Nashville. As the invasion force entered the Sulu Sea, a kamikaze struck Nashville, killing 133 people and wounding 190 more, including the task force commander, Brigadier General William C. Dunkel. The landings were made unopposed on December 15, 1944, and within two weeks Australian and American engineers had three airstrips in operation, but "not since Anzio had the navy experienced so much difficulty supporting an amphibious operation after the initial landing." The resupply convoys were repeatedly attacked by kamikaze aircraft and on December 26–27 a Japanese naval force attacked the area, sinking a destroyer and damaging other ships.[90]

The way was now clear for the invasion of Luzon. This time, based on different interpretations of the same intelligence data, Willoughby's G-2 Section at GHQ estimated the strength of General Tomoyuki Yamashita's forces on Luzon at 137,000, while that of Sixth Army estimated it at 234,000. The Sixth Army Brigadier General Clyde D. Eddleman attempted to lay out the reasons for the Sixth Army's assessment, but MacArthur's response was "Bunk!". He felt that even Willoughby's estimate was too high. "Audacity, calculated risk, and a clear strategic aim were MacArthur's attributes," and he was prepared to disregard the intelligence estimates. However, all the estimates were too low: Yamashita had more than 287,000 troops on Luzon.[91] This time MacArthur traveled on the USS Boise, watching as the ship was near-missed by a bomb and torpedoes fired by midget submarines.[92] The GHQ communiqué read: "The decisive battle for the liberation of the Philippines and the control of the Southwest pacific is at hand. General MacArthur is in personal command at the front and landed with his assault troops."[93]

MacArthur's primary concern was the capture of the port of Manila and the airbase at Clark Field, which were required to support future operations. He urged his front line commanders on.[94] On January 25, 1945 he moved his advanced headquarters forward to Hacienda Luisita, closer to the front than Krueger's at Calasiao.[95] On January 30, MacArthur ordered the 1st Cavalry Division's commander, Major General Verne D. Mudge, to conduct a rapid advance on Manila. On February 3, it reached the northern outskirts of Manila and the campus of the University of Santo Tomas where 3,700 internees were liberated.[96] Unknown to the Americans, Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi had decided to defend Manila to the death. The Battle of Manila raged for the next three weeks.[97] In order to spare the civilian population, MacArthur prohibited the use of air strikes, but thousands of civilians died in the crossfire or Japanese massacres.[98] He also refused to restrict the traffic of civilians who clogged the roads in and out of Manila, placing humanitarian concerns above military ones except for emergencies.[99] Most of MacArthur's 8,000-volume military library, which included books inherited from his father, was lost.[100] Nonetheless, he continued his habit of reading military history and biography until his death.[101] For his part in the capture of Manila, MacArthur was awarded his third Distinguished Service Cross.[102]

Southern Philippines

Although MacArthur had no specific directive from the Joint Chiefs to do so, and the fighting on Luzon was far from over, he committed the Eighth Army, Seventh Fleet and Thirteenth Air Force to a series of operations to liberate the remainder of the Philippines from the Japanese. A series of 52 amphibious landings were made in the central and southern Philippines between February and July 1945.[103] In the GHQ communiqué on July 5, MacArthur announced that the Philippines had now been liberated and all operations ended, although Yamashita still held out in northern Luzon.[104] Starting in May 1945, MacArthur used his Australian troops in the invasion of Borneo. MacArthur accompanied the assault on Labuan on USS Boise, and visited the troops ashore, along with Lieutenant General Sir Leslie Morshead and Air Vice Marshal William Bostock. En route back to his headquarters in Manila, he visited Davao, where he told Eichelberger that no more than 4,000 Japanese remained alive on Mindanao. A few months later, six times that number would surrender. In July 1945, he set out on Boise once more to be with the Australian 7th Division for the landing at Balikpapan.[105] MacArthur was awarded his fourth Distinguished Service Medal.[106]

In April 1945, MacArthur became commander in chief U.S. Army Forces Pacific (AFPAC), in charge of all Army and Army Air Force units in the Pacific, except the Twentieth Air Force. At the same time, Nimitz became commander of all naval forces. Command in the Pacific therefore remained divided. GHQ became AFPAC headquarters in addition to SWPA. MacArthur created two new commands, AFMIDPAC under Lieutenant General Robert C. Richardson, Jr., and AFWESPAC under Lieutenant General Wilhelm D. Styer, which absorbed USASOS and USAFFE.[107] This reorganization, which took some months to actually accomplish, was part of preparations for Operation Downfall, the invasion of Japan. The first phase, the invasion of Kyushu, known as Operation Olympic, was scheduled to commence on November 1, 1945.[108] The invasion was pre-empted by the surrender of Japan in August 1945. On September 2, MacArthur accepted the formal Japanese surrender aboard USS Missouri, thus ending hostilities in World War II.[109] In recognition of his role as a maritime strategist, the U.S. Navy awarded him the Navy Distinguished Service Medal.[110]

References

- ↑ Morton 1953, p. 19.

- ↑ Rogers 1990, p. 100.

- ↑ Morton 1953, p. 21.

- ↑ Morton 1953, p. 50.

- ↑ Morton 1953, pp. 35–37.

- ↑ Morton 1953, pp. 84–88.

- ↑ Morton 1953, p. 97.

- ↑ Morton 1953, p. 125.

- ↑ Morton 1953, p. 163.

- ↑ Rogers 1990, pp. 118–121.

- ↑ Rogers 1990, pp. 125–141.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 65–66.

- ↑ James 1975, p. 68.

- ↑ Rogers 1990, p. 165.

- ↑ Petillo 1979, pp. 107–117

- ↑ Halberstam 2007, p. 372.

- ↑ "But writer says she has proof – Claims MacArthur took half million denied", Ellensburg Daily Record, January 30, 1980, retrieved March 23, 2010

- ↑ James 1975, p. 98.

- ↑ Morton 1953, pp. 359–360.

- ↑ Rogers 1990, pp. 190–192.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 105–106.

- ↑ "Down but Not Out", Time, December 2, 1991, retrieved May 7, 2010

- ↑ Morton 1953, pp. 463–467.

- ↑ Morton 1953, p. 561.

- ↑ James 1975, p. 132.

- ↑ Arthur MacArthur, Jr., Arlington National Cemetery Website, retrieved May 7, 2010

- ↑ President Clinton Awards Medals of Honor to Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith and President Teddy Roosevelt, CNN.com, January 16, 2001, retrieved May 7, 2010

- 1 2 Gailey 1950, pp. 7–14.

- 1 2 Milner 1957, pp. 18–23.

- ↑ Horner, David (2000). "MacArthur, Douglas (1880–1964)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ↑ Rogers 1990, p. 253.

- ↑ James 1975, p. 80.

- ↑ Rogers 1990, p. 202.

- ↑ Milner 1957, p. 48.

- ↑ Rogers 1990, pp. 285–287.

- ↑ Drea 1992, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Drea 1992, p. 26.

- 1 2 James 1975, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Rogers 1990, p. 265.

- ↑ "The Press: Who Is Fooling Whom?", TIME, Time, January 15, 1951, retrieved May 7, 2010

- ↑ Milner 1957, pp. 39–41.

- ↑ Milner 1957, pp. 46–48.

- ↑ Milner 1957, pp. 53–55.

- ↑ Milner 1957, pp. 77–88.

- ↑ McCarthy 1959, p. 225.

- ↑ Milner 1957, pp. 91–92.

- ↑ McCarthy 1959, pp. 371–372.

- ↑ Luvaas 1972, pp. 32–33

- ↑ McCarthy 1959, p. 235.

- ↑ Milner 1957, p. 321.

- ↑ James 1975, p. 275.

- ↑ MacArthur 1964, p. 167.

- ↑ Honours and Awards – Douglas MacArthur (PDF), Australian War Memorial, retrieved March 15, 2010

- ↑ Rogers 1990, pp. 275–278.

- ↑ Craven & Cate 1948, pp. 417–418.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 197–198.

- ↑ Kenney 1949, p. 26.

- ↑ McCarthy 1959, p. 488.

- 1 2 3 Morison 1950, pp. 30–32.

- ↑ Morison 1950, p. 130.

- ↑ Hayes 1982, pp. 312–334.

- ↑ Willoughby 1966, p. 100.

- ↑ Dexter 1961, p. 12.

- ↑ Casey 1959, pp. 31–33.

- 1 2 Morison 1950, pp. 130–132.

- ↑ Leary 1988, p. 119

- ↑ James 1975, p. 220.

- ↑ James 1975, p. 327.

- ↑ MacArthur 1964, p. 179.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 328–329.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 364–365.

- ↑ Hayes 1982, pp. 487–490.

- ↑ MacArthur 1964, p. 189.

- ↑ Willoughby 1966, pp. 137–141.

- ↑ Willoughby 1966, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Taafe 1998, pp. 100–103.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 526–533.

- ↑ Drea 1992, pp. 152–159.

- ↑ Video: Third Army blasts Nazi Strongholds, 1944/11/02 (1944). Universal Newsreel. 1944. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 552–556.

- ↑ MacArthur 1964, p. 216.

- ↑ MacArthur 1964, p. 228.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 561–562.

- ↑ MacArthur 1964, pp. 222–231.

- ↑ MacArthur 1964, pp. 231–234.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 568–569.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 602–603.

- ↑ Five-Star Generals and Dates of Rank. United States Army Center of Military History, Fort Lesley J. McNair, Washington, DC. Last updated 4 August 2009. Accessed 12 May 2010.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 590–591.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 604–609.

- ↑ Drea 1992, pp. 180–187.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 619–620.

- ↑ James 1975, p. 622.

- ↑ James 1975, p. 629.

- ↑ James 1975, p. 623.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 632–633.

- ↑ Drea 1992, pp. 195–200.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 642–644.

- ↑ James 1975, p. 654.

- ↑ James 1975, p. 635.

- ↑ James 1985, p. 364.

- ↑ MacArthur 1964, p. 244.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 737–741.

- ↑ James 1975, p. 749.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 757–761.

- ↑ MacArthur 1964, p. 260.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 725–726.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 765–771.

- ↑ James 1975, pp. 786–792.

- ↑ MacArthur 1964, p. 265.

Bibliography

- Bartsch, William H. (2003), December 8, 1941: MacArthur's Pearl Harbor, College Station: Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 1-58544-246-1, OCLC 50920708

- Bix, Herbert P. (2000), Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, New York: Harper Collins, ISBN 0-06-019314-X, OCLC 43031388

- Casey, Hugh J., ed. (1959), Volume IV: Amphibian Engineer Operations, Engineers of the Southwest Pacific 1941–1945, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, OCLC 220327009

- Connaughton, Richard; Pimlott, David; Anderson, Duncan (1995), The Battle for Manila, London: Bloomsbury, ISBN 0-7475-3709-7, OCLC 260177075

- Costello, John (1981), The Pacific War, New York: Rawson, Wade, ISBN 0-89256-206-4, OCLC 7554100

- Costello, John (1994), Days of Infamy, New York: Pocket Books, ISBN 0-671-76985-5, OCLC 7671402

- Craven, Wesley Frank; Cate, James Lea, eds. (1948), "Vol. I, Plans and Early Operations", The Army Air Forces in World War II, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, OCLC 9828710, retrieved March 30, 2006

- Craven, Wesley Frank; Cate, James Lea, eds. (1950), "Vol. IV, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, August 1942 to July 1944", The Army Air Forces in World War II, University of Chicago Press, OCLC 9828710, retrieved October 20, 2006

- Dexter, David (1961), "The New Guinea Offensives", Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Canberra: Australian War Memorial, OCLC 2028994, retrieved November 21, 2009

- Dower, John (1999), Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-393-32027-5, OCLC 39143090

- Drea, Edward J. (1992), MacArthur's ULTRA: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942–1945, Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, ISBN 0-7006-0504-5, OCLC 23651196

- Drea, Edward; Bradsher, Greg; Hanyok, Robert; Lide, James; Petersen, Michael; Yang, Daqing (2006), Researching Japanese War Crimes Records, Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, ISBN 1-880875-28-4, OCLC 71126844

- Ferrell, Robert H. (2008), The Question of MacArthur's Reputation: Côte-de-Châttillon October 14–16, 1918, Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, ISBN 978-0-8262-1830-8, OCLC 227919803

- Franzwa, Gregory M.; Ely, William J. (1980), Leif Sverdrup: "... Engineer Soldier at his Best", Tucson: Patrice Press, ISBN 0-935284-12-5, OCLC 6091961

- Gailey, Harry A. (2004), MacArthur's Victory: The War in New Guinea, 1943-1944, New York: Presidio Press, ISBN 0-345-46386-2

- Gold, Hal (1996), Unit 731 Testimony, Boston: Tuttle, ISBN 0-8048-3565-9, OCLC 57440210

- Halberstam, David (2007), The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War, New York: Hyperion, ISBN 1-4013-0052-9, OCLC 137324872

- Hayes, Grace P. (1982), The History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in World War II: The War Against Japan, Annapolis: United States Naval Institute, ISBN 0-87021-269-9, OCLC 7795125

- Herzstein, Robert (2005), Henry Luce and the American Crusade in Asia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-83577-1, OCLC 56559249

- Imparato, E. T. (2000), General MacArthur: Speeches and Reports 1908-1964, Paducah, Kentucky: Turner Pub, ISBN 1-56311-589-1, OCLC 45603650

- James, D. Clayton (1970), "Volume 1, 1880–1941", The Years of MacArthur, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-10948-5, OCLC 60070186

- —— (1975), "Volume 2, 1941–1945", The Years of MacArthur, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-20446-1, OCLC 12591897

- —— (1985), "Volume 3, Triumph and Disaster 1945–1964", The Years of MacArthur, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-36004-8, OCLC 36211311

- Kenney, George C. (1949), General Kenney Reports: A Personal History of the Pacific War (PDF), New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, ISBN 0-912799-44-7, OCLC 16466573, retrieved February 20, 2009

- Leary, William M., ed. (1988), We Shall Return!: MacArthur's Commanders and the Defeat of Japan, 1942–1945, Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, ISBN 978-0-8131-9105-8, OCLC 17483104

- Leary, William M., ed. (2001), MacArthur and the American Century: A Reader, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-2930-5, OCLC 44420468

- Long, Gavin Merrick (1969), MacArthur as Military Commander, London: Batsford, ISBN 978-0-938289-14-2, OCLC 464094918

- Luvaas, Jay (1972), Dear Miss Em: General Eichelberger's war in the Pacific, 1942–1945, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-8371-6278-5, OCLC 415330

- MacArthur, Douglas (1964), Reminiscences of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, Annapolis: Bluejacket Books, ISBN 1-55750-483-0, OCLC 220661276

- Manchester, William (1983), American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880–1964, Laurel, ISBN 0-440-30424-5, OCLC 3844481

- McCarthy, Dudley (1959), South-West Pacific Area—First Year: Kokoda to Wau, Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Canberra: Australian War Memorial, OCLC 6152102, retrieved March 13, 2010

- Miller, Roger G. (Spring 2001), "A 'Pretty Damn Able Commander'—Lewis Hyde Brereton: Part II", Air Power History, 48 (1): 22–45, OCLC 46849079

- Milner, Samuel (1957), Victory in Papua, United States Army in World War II, Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History, ISBN 1-4102-0386-7, OCLC 1260772, retrieved March 13, 2010

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1950), "Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier: 22 July 1942–1 May 1944", History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, ISBN 0-7858-1307-1, OCLC 10310299

- Morton, Louis (1953), The Fall of the Philippines, United States Army in World War II, Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Army, ISBN 1-4102-1696-9, OCLC 29293689, retrieved March 13, 2010

- Mossman, B.; Stark, M. W. (1991), "Chapter XXIV: General of the Army, Douglas MacArthur, State Funeral", The Last Salute: Civil and Military Funeral, 1921–1969, pp. 216–262, retrieved March 11, 2010

- Pearlman, Michael D. (2008), Truman & MacArthur: Policy, Politics, and the Hunger for Honor and Renown, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-35066-2, OCLC 159919446

- Perret, Geoffrey (1996), Old Soldiers Never Die: The Life of Douglas MacArthur, New York: Random House, ISBN 0-679-42882-8, OCLC 32396366

- Petillo, Carol M. (February 1979), "Douglas MacArthur and Manuel Quezon: A Note on an Imperial Bond", Pacific Historical Review, University of California Press, Volume 48 (No. 1): 107–117, JSTOR 3638940

- Rogers, Paul P. (1990), The Good Years: MacArthur and Sutherland, New York: Praeger Publishers, ISBN 978-0-275-92918-3, OCLC 20452987

- —— (1991), The Bitter Years: MacArthur and Sutherland, New York: Praeger Publishers, ISBN 978-0-275-92919-0, OCLC 21523648

- Schaller, Michael (1985), The American Occupation of Japan: The Origins of the Cold War in Asia, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-503626-3, OCLC 11971554

- —— (1964), Douglas MacArthur: The Far Eastern General, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-7351-0354-2, OCLC 18325485

- Schnabel, James F. (1972), United States Army in the Korean War, Washington: United States Department of the Army, ISBN 1-4102-2485-6, OCLC 70157987

- Smith, Robert Ross (1963), Triumph in the Philippines, United States Army in World War II, Washington: United States Department of the Army, ISBN 0-16-023810-2, OCLC 946510

- Stanton, Shelby L. (1989), America's Tenth Legion, Novato, California: Presidio, ISBN 0-89141-258-1, OCLC 19921899

- Taaffe, Stephen (1998), MacArthur's Jungle War: The 1944 New Guinea Campaign, Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, ISBN 0-7006-0870-2, OCLC 37107216

- Torricelli, Robert G.; Carroll, Andrew; Goodwin, Doris Kearns (2008), In Our Own Words Extraordinary Speeches of the American Century, Paw Prints, ISBN 1-4395-6895-2, OCLC 262883456

- Valley, David J. (2000), Gaijin Shogun: General Douglas MacArthur, Stepfather of Postwar Japan, Sektor Company, ISBN 0-9678175-2-8, OCLC 45586737

- Weintraub, Stanley (2000), MacArthur's War: Korea and the Undoing of an American Hero, New York: Free Press, ISBN 0-684-83419-7, OCLC 41548333

- Willoughby, Charles A., ed. (1966), "Japanese Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area Volume II – Part I", Reports of General MacArthur, Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History, OCLC 482111659, retrieved February 10, 2009