Doomsday Clock

The Doomsday Clock is a symbolic clock face that represents a countdown to possible global catastrophe (e.g., nuclear war or climate change). It has been maintained since 1947 by the members of The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists' Science and Security Board,[2] who are in turn advised by the Governing Board and the Board of Sponsors, including 18 Nobel Laureates. The closer they set the Clock to midnight, the closer the scientists believe the world is to global disaster.

Originally, the Clock, which hangs on a wall in The Bulletin's office in the University of Chicago,[3] represented an analogy for the threat of global nuclear war; however, since 2007 it has also reflected climate change,[4] and new developments in the life sciences and technology that could inflict irrevocable harm to humanity.[5] The most recent officially announced setting—three minutes to midnight—was made in January 2015 due to "[un]checked climate change, global nuclear weapons modernizations, and outsized nuclear weapons arsenals".[6] This setting was retained in January 2016.[7]

History

The Clock's origin can be traced to the international group of researchers called the Chicago Atomic Scientists, who had participated in the Manhattan Project.[3] After the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they began publishing a mimeographed newsletter and then the magazine, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which, since its inception, has depicted the Clock on every cover. The Clock was first represented in 1947, when The Bulletin co-founder Hyman Goldsmith asked artist Martyl Langsdorf (wife of Manhattan Project research associate and Szilárd petition signatory Alexander Langsdorf, Jr.) to design a cover for the magazine's June 1947 issue. As Eugene Rabinowitch, another co-founder of The Bulletin, explained later,

The Bulletin's clock is not a gauge to register the ups and downs of the international power struggle; it is intended to reflect basic changes in the level of continuous danger in which mankind lives in the nuclear age...[8]

In January 2007, designer Michael Bierut, who was on The Bulletin's Governing Board, redesigned the Clock to give it a more modern feel. In 2009, The Bulletin ceased its print edition and became one of the first print publications in the U.S. to become entirely digital; the Clock is now found as part of the logo on The Bulletin's website. Information about the Doomsday Clock Symposium,[9] a timeline of the Clock's settings,[6] and multimedia shows about the Clock's history and culture[10] can also be found on The Bulletin's website.

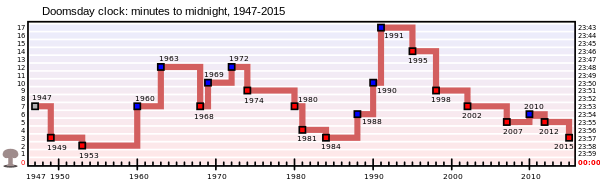

The 5th Doomsday Clock Symposium[9] was held on November 14, 2013, in Washington, D.C.; it was a daylong event that was open to the public and featured panelists discussing various issues on the topic "Communicating Catastrophe". There was also an evening event at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in conjunction with the Hirshhorn's current exhibit, "Damage Control: Art and Destruction Since 1950".[11] The panel discussions, held at the American Association for the Advancement of Science, were streamed live from The Bulletin's website and can still be viewed there.[12] Reflecting international events dangerous to humankind, the Clock's hands have been adjusted 21 times since its inception in 1947,[13] when the Clock was initially set to seven minutes to midnight.

Symbolic timepiece changes

In 1947, during the Cold War, the Clock was started at seven minutes to midnight and was subsequently advanced or rewound per the state of the world and nuclear warfare prospects. The Clock's setting is decided by The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists's Science and Security Board and is an adjunct to essays published in The Bulletin on global affairs. The Clock is not set and reset in real time as events occur; rather than respond to each and every crisis as it happens, the Science and Security Board meets twice annually to discuss global events in a deliberative manner. The closest nuclear war threat, the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, reached crisis, climax, and resolution before the Clock could be set to reflect that possible doomsday.[14]

| Year | Minutes to midnight | Change | Reason | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1947 |  | 7 | — | The initial setting of the Doomsday Clock. |

| 1949 |  | 3 | -4 | The Soviet Union tests its first atomic bomb, officially starting the nuclear arms race. |

| 1953 |  | 2 | -1 | The United States and the Soviet Union test thermonuclear devices within nine months of one another. (This is the Clock's closest approach to midnight since its inception.) |

| 1960 |  | 7 | +5 | In response to a perception of increased scientific cooperation and public understanding of the dangers of nuclear weapons (as well as political actions taken to avoid "massive retaliation"), the United States and Soviet Union cooperate and avoid direct confrontation in regional conflicts such as the 1956 Suez Crisis. Scientists from various countries help establish the International Geophysical Year, a series of coordinated, worldwide scientific observations between nations allied with both the United States and the Soviet Union, and the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, which allow Soviet and American scientists to interact. |

| 1963 |  | 12 | +5 | The United States and the Soviet Union sign the Partial Test Ban Treaty, limiting atmospheric nuclear testing. |

| 1968 |  | 7 | -5 | The involvement of the United States in the Vietnam War intensifies, the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 takes place, and the Six-Day War occurs in 1967. France and China, two nations which have not signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty, acquire and test nuclear weapons (the 1960 Gerboise Bleue and the 1964 596, respectively) to assert themselves as global players in the nuclear arms race. |

| 1969 |  | 10 | +3 | Every nation in the world, with the notable exceptions of India, Israel, and Pakistan, signs the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. |

| 1972 |  | 12 | +2 | The United States and the Soviet Union sign the first Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I) and the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty. |

| 1974 |  | 9 | -3 | India tests a nuclear device (Smiling Buddha), and SALT II talks stall. Both the United States and the Soviet Union modernize multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs). |

| 1980 |  | 7 | -2 | Unforeseeable end to deadlock in American–Soviet talks as the Soviet–Afghan War begins. As a result of the war, the U.S. Senate refuses to ratify the SALT II agreement. |

| 1981 |  | 4 | -3 | The Clock is adjusted in early 1981.[15] The Soviet war in Afghanistan toughens the U.S.' nuclear posture. President Jimmy Carter withdraws the United States from the 1980 Summer Olympic Games in Moscow. The Carter administration considers ways in which the United States could win a nuclear war. Ronald Reagan becomes president, scraps further arms reduction talks with the Soviet Union, and argues that the only way to end the Cold War is to win it. Tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union contribute to the danger of the nuclear annihilation. |

| 1984 |  | 3 | -1 | Further escalation of the tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, with the ongoing Soviet–Afghan War intensifying the Cold War. U.S. Pershing II medium-range ballistic missile and cruise missiles are deployed in Western Europe.[15] Ronald Reagan pushes to win the Cold War by intensifying the arms race between the superpowers. The Soviet Union and its allies (except Romania) boycott the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, as a response to the U.S-led boycott in 1980. |

| 1988 |  | 6 | +3 | In December 1987, the Clock is moved back three minutes as the United States and the Soviet Union sign the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, to eliminate intermediate-range nuclear missiles, and their relations improve.[16] |

| 1990 |  | 10 | +4 | The Fall of the Berlin Wall and the Iron Curtain, along with the unification of Germany, mean that the Cold War is nearing its end. |

| 1991 |  | 17 | +7 | The United States and Soviet Union sign the first Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I), and the Soviet Union is dissolved on December 26. (This is the furthest from midnight the Clock has been since its inception.) |

| 1995 |  | 14 | -3 | Global military spending continues at Cold War levels amid concerns about post-Soviet nuclear proliferation of weapons and brainpower. |

| 1998 |  | 9 | -5 | Both India (Pokhran-II) and Pakistan (Chagai-I) test nuclear weapons in a tit-for-tat show of aggression; the United States and Russia run into difficulties in further reducing stockpiles. |

| 2002 |  | 7 | -2 | Little progress on global nuclear disarmament. United States rejects a series of arms control treaties and announces its intentions to withdraw from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, amid concerns about the possibility of a nuclear terrorist attack due to the amount of weapon-grade nuclear materials that are unsecured and unaccounted for worldwide. |

| 2007 |  | 5 | -2 | North Korea tests a nuclear weapon in October 2006,[17] Iran's nuclear ambitions, a renewed American emphasis on the military utility of nuclear weapons, the failure to adequately secure nuclear materials, and the continued presence of some 26,000 nuclear weapons in the United States and Russia.[18] After assessing the dangers posed to civilization, climate change was added to the prospect of nuclear annihilation as the greatest threats to humankind.[19] |

| 2010 |  | 6 | +1 | Worldwide cooperation to reduce nuclear arsenals and limit effect of climate change.[6] New START agreement is ratified by both the United States and Russia, and more negotiations for further reductions in the American and Russian nuclear arsenal are already planned. 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, Denmark results in the developing and industrialized countries agreeing to take responsibility for carbon emissions and to limit global temperature rise to 2 degrees Celsius. |

| 2012 |  | 5 | -1 | Lack of global political action to address global climate change, nuclear weapons stockpiles, the potential for regional nuclear conflict, and nuclear power safety.[20] |

| 2015 |  | 3 | -2 | Concerns amid continued lack of global political action to address global climate change, the modernization of nuclear weapons in the United States and Russia, and the problem of nuclear waste.[21] |

| 2016 |  | 3 | — |

See also

References

- ↑ http://thebulletin.org/timeline

- ↑ "Science and Security Board". The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

- 1 2 "Doomsday Clock moving closer to midnight?". The Spokesman-Review. October 16, 2006.

- ↑ Stover, Dawn (September 26, 2013). "How Many Hiroshimas Does it Take to Describe Climate Change?". The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

- ↑ "'Doomsday Clock' Moves Two Minutes Closer To Midnight". The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Timeline". The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. January 2015.

- ↑ "It is still three minutes to midnight". The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. January 2016.

- ↑ "The Doomsday Clock". The Southeast Missourian. February 22, 1984.

- 1 2 "Doomsday Clock Symposium". The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ↑ "A Timeline of Conflict, Culture, and Change". The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Damage Control: Art and Destruction Since 1950". Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. 2013.

- ↑ "5th Doomsday Clock Symposium". The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Doomsday Clock ticks closer to midnight". Washington Post. January 10, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- ↑ "Remembering the Cuban Missile Crisis". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- 1 2 "Doomsday Clock at 3'til midnight". The Daily News. December 21, 1983.

- ↑ "Hands of the 'Doomsday Clock' turned back three minutes". The Reading Eagle. December 17, 1987.

- ↑ "The North Korean nuclear test". The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- ↑ "'Doomsday Clock' Moves Two Minutes Closer To Midnight". The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. 17 January 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ "Nukes, climate push 'Doomsday Clock' forward". MSNBC. 2012-01-15. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ↑ "Doomsday Clock moves to five minutes to midnight". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved 2013-06-29.

- ↑ Casey, Michael (22 January 2015). "Doomsday Clock moves two minutes closer to midnight". CBS News. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Doomsday Clock. |