Demétre Chiparus

Demétre Haralamb Chiparus (16 September 1886 – 22 January 1947) was a Romanian Art Deco era sculptor who lived and worked in Paris, France. He was one of the most important sculptors of the Art Deco era.

Life

Demétre H. Chiparus, also known as Dumitru Chipăruş, was born in Dorohoi, Romania, the son of Haralamb and Saveta Chiparus. In 1909 he went to Italy, where he attended the classes of Italian sculptor Raffaello Romanelli. In 1912 he traveled to Paris to attend the Ecole des Beaux Arts to pursue his art at the classes of Antonin Mercie and Jean Boucher.[1] Demétre Chiparus died in 1947, suffering a stroke on returning from studying animals at the zoo in Vincennes.[1] He was buried in Bagneux Cemetery, just south of Paris.

Work

Early career

The first sculptures of Chiparus were created in the realistic style and were exhibited at the Salon of 1914. He employed the combination of bronze and ivory, called chryselephantine, to great effect. Most of his renowned works were made between 1914 and 1933. The first series of sculptures manufactured by Chiparus were the series of the children.

Later career

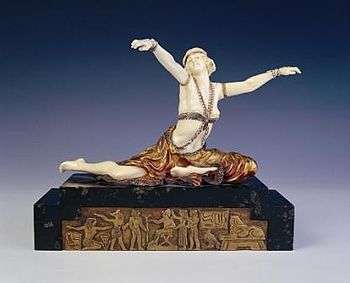

The mature style of Chiparus took shape beginning in the 1920s. His sculptures are remarkable for their bright and outstanding decorative effect. Dancers of the Russian Ballet, French theatre,[1] and early motion pictures were among his more notable subjects and were typified by a long, slender, stylized appearance. His work was influenced by an interest in Egypt, after Pharaoh Tutankhamen's tomb was excavated.

Chiparus created one of the most iconic bronzes in 1928 called "Danseuse au cerceau" or "Ring Dancer" inspired in the famous and prodigious dancer Zoula de Boncza of the Parisian "Folies Bergere", a first dancer of The Belgrado Royal Opera and a Mime dancer of "l'Opéra-Comique" in Paris. Later in life Zoula de Boncza, a descendant of Polish nobility and one of Loie Fuller best students, created a book published in 1961: the dance method "La Danse classique san barre". The book was published with texts from Eugène de Rijac and Illustrations by Alexandre Berlant and Yvonne Breton.

He worked primarily with the Edmond Etling and Cie Foundry in Paris administrated by Julien Dreyfus. Les Neveux de J. Lehmann was the second foundry who constantly worked with Chiparus and produced the sculptures cast from his models. He based many of his works on the ballet and the theatre, one particular theme being the Ballets Russes from which resulted "The Russian Dancers" depicting Vaslav Nijinsky and Ida Rubenstein in that role in Schéhérazade.[1]

The Salon

Chiparus rarely exhibited at the Salon. In 1923 he showed his “Javelin Thrower” and in 1928 exhibited his “Ta-Keo” dancer, which was edited by the manufacture Friedrich Goldscheider. During the period of Nazi persecution and the World War II the foundries discontinued production of work by Chiparus. The economic situation of that time was not favorable to the development of decorative arts and circumstances for many sculptors worsened.

For a time in the early 1940s almost no works of Chiparus were sold but he continued sculpting for his own pleasure, depicting animals in the Art Deco style. At the 1942 Paris Salon, the plaster sculptures “Polar Bear” and “American Bison” were exhibited and in 1943 he showed a marble “Polar Bear” and plaster “Pelican”.

Style

Sculptures of Dimitri Chiparus represent the classical manifestation of Art Deco style in decorative bronze ivory sculpture. Traditionally, four factors of influence over the creative activity of the artist can be distinguished: Serge Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, ancient Egyptian art, and French theatre. Early motion pictures were among his more notable subjects and were typified by figures with a long, slender, stylized appearance. Some of his sculptures were directly inspired by Russian dancers.[1] For example, faces of “Persian Dance” figures reveal the likenesses of Vaslav Nijinsky and Ida Rubinstein, and the dress in “Starfish Girl” exactly reproduces the sketch for Goldfish’s dress from the ballet “Underwater kingdom” by Lev Annensky. Chiparus could have been influenced by Russian ballets indirectly, through the performances of French music halls and cabarets which bore traces of the strong impact of Russian ballet. Quite often, Chiparus used the photos of Russian and French dancers, stars and models from fashion magazines of his time.

After the tomb of Tutankhamun was discovered in 1922, the art of ancient Egypt and the East came to French fashion and is also reflected in the creative activity of Chiparus. Several sculptures by Dimitri Chiparus and Claire Colinet represent queen Cleopatra and Egyptian dancers. The sculptures of Chiparus reflect his time and 1920-1930s sentiment of “folle”. Coming from the oldest French tradition of high-quality and extra-artistic decorative arts, the sculptures of Dimitri Chiparus combine elegance and luxury, embodying the spirit of the Art Deco epoch.

Collector interest in the work of Chiparus appeared in the 1970s and has flourished since the 1990s. A major collection of Chiparus' work is on display in the permanent collection of Casa Lis, the art nouveau and art deco museum in Salamanca, Espana.

Death and legacy

Demétre Chiparus died in Paris in 1947, suffering a stroke on returning from studying animals at the zoo in Vincennes.[1] He was buried in Bagneux Cemetery, just south of Paris. Chiparus is remembered as one of the most important artists of the Art Deco era.

Gallery

References

Sources

- Alberto Shayo Chiparus - Master of Art Deco (Abbeville Press, Publishers 1993) ISBN 1-55859-475-2

- Victor Arwas. «Art deco» — London: 1992

- Victor Arwas. «Art Deco Sculpture: Chryselephantine Statuettes of the Twenties and Thirties» — London: 1975

- Bryan Catley. «Art Deco and other Figures» — Woodbridge, Suffolk: 1978

- Alexey Witt. «Demetre Chiparus - the great sculptor of an era of the Art deco» - A. Witt & D. Leontyev, Moscow: 2015

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Demetre Chiparus. |

- Gallery of sculptures

- Examples of his works

- Demétre Chiparus in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website