Deggendorf

| Deggendorf | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| ||

Deggendorf | ||

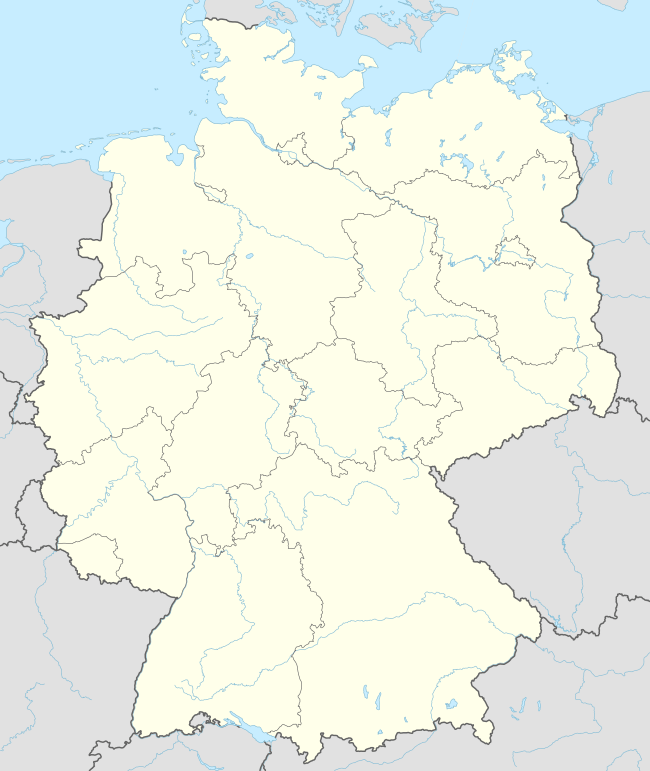

Location of Deggendorf within Deggendorf district  | ||

| Coordinates: 48°50′N 12°58′E / 48.833°N 12.967°ECoordinates: 48°50′N 12°58′E / 48.833°N 12.967°E | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | Bavaria | |

| Admin. region | Niederbayern | |

| District | Deggendorf | |

| Government | ||

| • Lord Mayor | Dr. Christian Moser (CSU) | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 77.21 km2 (29.81 sq mi) | |

| Population (2015-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 32,189 | |

| • Density | 420/km2 (1,100/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 94469 | |

| Dialling codes | 0991 | |

| Vehicle registration | DEG | |

| Website | www.deggendorf.de | |

Deggendorf (Bavarian: Degndorf) is a town in Bavaria, capital of the Deggendorf district.

It is located on the left bank approximately in the middle between the Danube cities of Regensburg and Passau. The crossing railway bridge situated on the Danube kilometers 2286th forms the natural border to the city about south-east of the Danube, it is the other side at the foot of the central Bavarian Forest. A few miles downstream, near the district Deggenau, the Isar flows into the Danube.

Historical background

Early history

The earliest traces of settlement in the area are found near the Danube, about 8,000 years ago. Both Bronze Age and Celtic era archeological finds indicate continuous habitation through the years.

The first written mention of Deggendorf occurs in 868, and Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor established his supremacy over the area in 1002. It appears as a town in 1212. Heinrich (d. 1290) of the Landshut branch of the ruling family of Bavaria made it the seat of a custom-house; and in 1331 it became the residence of Heinrich III of Natternberg (d. 1333), so-called from a castle in the neighbourhood.[2]

Massacre of 1337

In the beginning of the 1330s, Deggendorf was an expanding market town with commerce and trade. In the beginning of this new decade, however, it was caught in the middle of a conflict between the Bavarian dukes. A fire damaged large parts of the town. Possibly this was one of the reasons for the high levels of debt to the local Jewish community.[3]:196

The first reference to the murder of the Jews is found in an official document by Duke Heinrich XIV originating from 1338. In this document, the duke forgave the citizens of Deggendorf for the murder of the Jews and spared them any kind of punishment. He even granted them the right to keep all the possessions they took from the Jews.[3]:199–202

Further clues to the murders are found, for example, in the annals of some important monasteries of the time and in the works of Johann von Viktring (d. ca. 1346). For 1338, these sources mention a plague of locusts which destroyed much of that year’s crop. Johann von Viktring refers to this infestation in connection to the murder of the Jews of Deggendorf.[3]:203–221, esp. 212–214

Yet, the inscription in the basilica of Deggendorf differs from all former sources. As the date of events it gives 1337. The Jews are purported to have set fire to the town. The body of God was found so that the community of Deggendorf started to build a church.

''"Im Jahre des Herrn 1337, am nächsten Tag nach St. Michaels-Tag, wurden die Juden erschlagen, die Stadt zündeten sie an, da wurde Gottes Leichnam gefunden, das sahen Frauen und Männer, da hob man das Gotteshaus zu bauen an."

In the year of the Lord 1337, on the day after Michaelmas, the Jews were slain. They had set fire to the town. Then the body of God was found. This was seen by women and men and the building of the house of God was begun.

The wrong date indicates that this inscription stems from a much later date. The mention of the body of God points to a host desecration.[3]:223–226

It must be assumed that the accusation of host desecration had already taken on a life of its own at that time so that further explanations were not needed. Everyone was familiar with the narratives of this legend.[4]

The fully formed legend of the host desecration by the Jews of Deggendorf and about the miracles happening after their "punishment" appears in a composite manuscript in the library of the monastery St Emmeram in Regensburg not before the 15th century. "Das Gedicht von den Deggendorfer Hostien" (The poem of the hosts of Deggendorf) has strictly no credibility at all. Its sudden appearance centuries after the actual events took place makes just one piece of evidence for this. Its content is schematic and clichéd. Stereotypically, Easter Day is given as the date and the accusation of well poisoning is added even though it had never been mentioned before in this context. Details that could be interpreted as specific to Deggendorf are left out. The only name given is that of Hartmann von Degenberg who could not be identified as an actual historical person.[3]:230–244

A complete deformation of reality becomes manifest in the poem. What happened in Deggendorf in 1338 is probably that the pogrom came about because of the high debts the Christian citizens owed the Jews. The locusts destroying much of the crop tightened the situation. The end of September or the beginning of October 1338 is likely the correct date (around the payday on Michaelmas.[3]:287–288) This means the Jews were murdered for economic reasons. Events were reworked later to justify the act so that in the 15th century the stereotypical legend took on its own life.[3]:287–288

The course of the "Deggendorfer Gnad"

Genesis and development of attendances

In the years following the economic downturn and the aforementioned massacre, Deggendorf regained some of its former wealth. Thus, the construction of the basilica ("Heilig-Grab-Kirche") could be completed by 1400.[5]:105f By the beginning of the 15th century the fully formed legend had already spread far enough to encourage more and more people to pilgrimage to Deggendorf.[5]:107 An average of 40.000 people per year traveled to Deggendorf and its famous hosts.[3]:506 The development of the pilgrimage to become a time of worship of the magic hosts of Deggendorf was particularly promoted by pastor Johannes Sartorius (1599–1609) and Duke Albrecht of Bavaria (1584–1666).[5]:107 The much admired hosts, however, had been retrospectively purchased and had to be replaced regularly.[5]:107 During the 18th and 19th century and especially in 1737 (year of the 400-year-jubilee) the "Gnad" reached its peak attracting six-figure attendances. The pilgrimage constituted one of the major factors of the Deggendorf economy.[3]:507 Yet, after its peak, attendances decreased steadily until 1927. In 1970, only about 10.000 pilgrims, mainly from the Deggendorf area, took part in the festivities.[3]:509f The supra-regional significance of the "Deggendorfer Gnad" had been lost. In addition, only older people seemed to keep participating in the Gnad. Due to these developments the town pursued a thorough advertising campaign combined with a redesign of the festivities in 1976 resulting in a slight increase in younger peoples’ attendance figures.[3]:509f The growing critique of the "Deggendorfer Gnad" can also be regarded as a reason for the decrease in attendance figures.

The course of the pilgrimage

The pilgrimage started with a ceremonial inauguration and the ritualized unbarring of the "Gnadenpforte," aka the church door of the basilica "Heilig-Grab-Kirche," on 29 September (Michaelmas Day).[3]:509f

On 30 September, a church parade with the magic hosts in a monstrance constituted the highlight of the pilgrimage. In 1962, a vespertine church parade was added to the programme in order to increase the pilgrimage’s appeal.[3]:506

The pilgrimage concluded with a sermon at 4pm on 4 October and the ritualistic barring of the basilica’s church door.[3]:534f In 1973, the vespertine church parade was rescheduled from 30 September to 4 October, and from then on combined with the concluding rituals.

End of the pilgrimage

It was not before the 1960s that the "Deggendorfer Gnad" attracted more and more criticism. It was demanded to remove all anti-Jewish depictions showing them in the middle of the alleged host desecration. Among these was a cycle of sixteen oil paintings, the hosts themselves and the "Judenstein" (an anvil with Jewish figures around it and floating hosts).[3]:660–661

Even though the debate quickly became a heated topic in the press – abroad as well as domestic[3]:664 – it took until 1968 for the first four of the sixteen oil paintings to finally be removed,[3]:689 which was the first concession. The debate quickly polarized. While some saw the "Deggendorfer Gnad" as anti-Semitism in its purest form, others thought it just a piece of Bavarian folklore.[3]:668–669 The diocesan chapter of Regensburg invoked the long tradition of the pilgrimage and assured that the Jews as its cause were hardly ever mentioned in the sermons.[3]:669–671

In the 1980s, Manfred Eder (University of Regensburg) started work on his doctoral thesis carefully researching the origin and development of the "Deggendorfer Gnad". On the basis of his findings, the diocese of Regensburg finally decided to abolish the pilgrimage. Bishop Manfred Müller asked for forgiveness for the centuries-long defamation of the Jews.[5]:102–109

Displaced persons camp

Deggendorf was the site of a displaced persons camp for Jewish refugees after World War II. It housed approximately 2,000 refugees, who created a cultural center that included two newspapers, the Deggendorf Center Review and Cum Ojfboj, a theater group, synagogue, mikvah, kosher kitchen, and more. The camp even issued its own currency known as the Deggendorf Dollar. Many of the camp's residents were survivors of the concentration camp at Theresienstadt. The displaced persons camp closed on 15 June 1949.

Sons and daughters of the town

- Django Asül (born 1972), comedian

- August Högn (1878-1961), teacher, local historian and composer

- Georg Rörer (1492-1557), Lutheran theologian

- Kathrin Passig (born 1970), journalist and writer

- Gudrun Stock (born 1995), cyclist

References

- ↑ "Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes". Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik und Datenverarbeitung (in German). June 2016.

- ↑

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Deggendorf". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 932.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Deggendorf". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 932. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Manfred Eder, Die "Deggendorfer Gnad". Entstehung und Entwicklung einer Hostienwallfahrt im Kontext von Theologie und Geschichte. Deggendorf 1992.

- ↑ cp. Gerhard Czermak, Christen gegen Juden. Geschichte einer Verfolgung. Nördlingen 1989; here: pp. 59–63. Friedrich Lotter, Hostienfrevelvorwurf und Blutwunderfälschung bei den Judenverfolgungen von 1298 ('Rintfleisch') und 1336–1338 ('Armleder'). In: Fälschungen im Mittelalter. Teil 5: Fingierte Briefe, Frömmigkeit und Realienfälschungen (= Monumenta Germaniae Historica 33.5). Hannover 1988, pp. 533–583.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Manfred Eder, "Wär besser euer Moses im Nilschlamm ersoffen…" Hintergründe, Geschichte und Ender der umstrittenen Hostienwallfahrt zur "Deggendorfer Gnad". In: Jüdisches Museum Wien (Hrsg.), Die Macht der Bilder. Antisemitische Vorurteile und Mythen. Wien 1995.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Deggendorf. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Deggendorf. |

- City of Deggendorf home page

-

"Deggendorf". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"Deggendorf". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Deggendorf in christlichen und jüdischen Nachschlagewerken Stadt Deggendorf (Research at haGalil dated 4 June 2012)

- "Deggendorf: History of the coat-of-arms" (in German). Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte.

- "digitalised image". Photograph Archive of Old Original Documents (Lichtbildarchiv älterer Originalurkunden). University of Marburg. Urkunde Kaiser Heinrichs II., Regensburg, 20 November 1002 with first record of the place name of Deggindorf

- Template:LStDV GKZ