Modernization of the People's Liberation Army

The military modernization program of the People's Liberation Army which began in the late 1970s had three major focuses. First, under the political leadership of Deng Xiaoping, the military became disengaged from civilian politics and, for the most part, resumed the political quiescence that characterized its pre-Cultural Revolution role. Deng reestablished civilian control over the military by appointing his supporters to key military leadership positions, by reducing the scope of the PLA's domestic non-military role, and by revitalizing the party political structure and ideological control system within the PLA.

Second, modernization required the reform of military organization, doctrine, education and training, and personnel policies to improve combat effectiveness in combined-arms warfare. Among the organizational reforms that were undertaken were the creation of the state Central Military Commission, the streamlining and reduction of superfluous PLA forces, civilianization of many PLA units, reorganization of military regions, formation of group armies, and enactment of the new Military Service Law in 1984. Doctrine, strategy, and tactics were revised under the rubric of "people's war under modern conditions," which envisaged a forward defense at selected locations near China's borders, to prevent attack on Chinese cities and industrial sites, and emphasized operations using combined-arms tactics. Reforms in education and training emphasized improving the military skills and raising the education levels of officers and troops and conducting combined-arms operations. New personnel policies required upgrading the quality of PLA recruits and officer candidates, improving conditions of service, changing promotion practices to stress professional competence, and providing new uniforms and insignia.

The third focus of military modernization was the transformation of the defense establishment into a system capable of independently maintaining a modern military force. As military expenditures remained relatively constant, reforms concentrated on reorganizing the defense research and development and industrial base to integrate civilian and military science and industry more closely. Foreign technology was used selectively to upgrade weapons. Defense industry reforms also resulted in China's entry into the international arms market and the increased production of civilian goods by defense industries. The scope of PLA economic activities was reduced, but the military continued to participate in infrastructure development projects and initiated a program to provide demobilized soldiers with skills useful in the civilian economy.

Currently, China focus on domestic weapon designs and manufacturing, while still importing certain military products from Russia such as jet engines. China decided to become independent in its defense sector and become competitive in global arms markets; its defense sector is rapidly developing and maturing. Gaps in certain capability remain—most notably in the development of some sophisticated electronic systems and sufficiently reliable and powerful propulsion systems—but China's defense industry is now producing warships and submarines, land systems and aircraft that provide the Chinese armed forces with a capability edge over most military operating in the Asia-Pacific. Where indigenous capability still falls short, China procures from Russia and, until local industry eventually bridges the gap, it hopes that quantity will overcome quality.[1] China's 2015 Defense White Paper called for "independent innovation" and the "sustainable development" of advanced weaponry and equipment.[2]

According to national interest, Chinese industry can still learn much from Russia, but in many areas it has caught up with its model. The vibrancy of China’s tech sector suggests that Chinese military technology will leap ahead of Russian tech in the next decade.[3]

Civil-military relations

Lines between civilian and military leadership and institutions in China have been indistinct. All high-ranking military leaders have high-level party positions, and many high-ranking party officials have some military experience. When military leaders participate in national policy making, therefore, it is not clear whether their positions reflect PLA corporate interests or the interests of groups that cut across institutional lines. In general, in times where there was national leadership consensus on national policy, such as in the 1950s, the PLA was politically quiescent. Once the PLA was drawn into civilian politics during the Cultural Revolution, the military became divided along the lines of civilian factions. As long as the national leadership remained divided on a number of policy issues, the PLA, fearing factional struggles and political instability, was reluctant to leave the political scene. When Deng Xiaoping was rehabilitated in 1977, however, the stage was set for the withdrawal of the military from politics and a partial return to the PLA's previous political passivity.

Political role of the PLA

Deng Xiaoping's efforts in the 1980s to reduce the political role of the military stemmed from his desire to reassert civilian control over the military and to promote military modernization. To accomplish his objectives, Deng revitalized the civilian party apparatus and leadership and built a consensus on the direction of national policy. He also established personal control over the military through personnel changes, and he reduced the scope of the PLA's domestic political, economic, and social roles. Finally, he strengthened party control over the military through institutional reforms and political and ideological education. The revitalization of the party and the establishment of a consensus on national policy assured top military leaders of political stability and a vigorous party capable of handling national and regional affairs without extensive military participation (see Four Modernizations, 1979–82).

Deng's personal political control was established over the military through his assumption of the position of chairman of the party Central Military Commission in June 1981 and through his appointment of his supporters to key positions in the party Central Military Commission, Ministry of National Defense, and the PLA's General Staff Department, General Political Department, and General Logistics Department. Occasional replacement of military region and military district commanders also strengthened Deng's hand. Military leaders who objected to Deng's policies were replaced with more amenable personnel.

The creation of the state Central Military Commission in 1982 aimed to further strengthen civilian control over the military by stressing the PLA's role as defender of the state and by establishing another layer of supervision parallel to party supervision. The civilianization of several PLA corps and internal security units reduced the size of the PLA and the scope of its involvement in civilian affairs. The placement of defense industries under civilian control and the transfer or opening up of military facilities, such as airports and ports, to civilian authorities also limited the PLA's influence in economic and political matters. Propaganda using the PLA as a model for society also diminished, and emphasis was placed on the PLA's military rather than political role.

Party control

In addition to making personnel changes, Deng revitalized party control over the PLA and diffused the military's political power by designating provincial-level, municipal, district, and county party committee secretaries to serve concurrently as the first political commissars of their equivalent-level units in the regional PLA. The percentage of PLA personnel permitted to join the party was limited by restricting party membership to military academy graduates. Political and ideological training stressed the military rather than the social, ideological, or economic role of the PLA. Special effort was made to discredit the PLA's role in the Cultural Revolution; the PLA's support for the left was described as incorrect because it caused factionalism within the military. While emphasizing the necessity and appropriateness of reforms to modernize the military, political education also sought to guarantee military support for Deng's reform agenda. Beginning in 1983 a rectification campaign (part of the party-wide rectification campaign aimed primarily at leftists) reinforced this kind of political and ideological training (see History of the People's Republic of China (1976–1989)).

Beginning in the late 1970s, Deng Xiaoping succeeded in decreasing military participation in national-level political bodies. Military representation on the Political Bureau fell from 52 percent in 1978 to 30 percent in 1982, and military membership in the party Central Committee declined from 30 percent in 1978 to 22 percent in 1982. Most professional military officers shared common views with the Deng leadership over military modernization and the fundamental direction of national policy, and they willingly limited their concerns to military matters. Nonetheless, some elements in the PLA continued to voice their opinions on non-defense matters and criticized the Deng reform program. Dissent centered on prestigious military leaders, notably Ye Jianying, who feared that ideological de-Maoification, cultural liberalization, and certain agricultural and industrial reforms deviated from Marxist values and ideals. The Deng leadership contained these criticisms with the help of the personnel changes, political education, and the rectification campaign just mentioned. In this way it was able to keep military dissent within bounds that did not adversely affect civil-military relations.

Popular attitudes toward the PLA

Starting in the late 1970s, popular attitudes toward the PLA also underwent considerable changes. In the 1950s and 1960s, the military's prestige was very high because of its wartime exploits, because it was held up as a role model for society, and because of its participation in civilian construction projects. But the power gained by the PLA during the Cultural Revolution reawakened civilian resentment of military privileges and abuses of power. By the early 1980s, with the restriction of the PLA's domestic role and the implementation of agricultural reforms offering greater opportunities for rural youth, the PLA's reputation as a prestigious, elite, Marxist-model organization and a promising channel for social mobility was severely tarnished. Society's perception of the military appeared to be returning to the traditional viewpoint that "one doesn't make nails out of good iron; one doesn't make soldiers out of good men." To restore this damaged image in the late 1980s, the media extolled the PLA's martial virtues and the great strides made in military modernization in recent years.

Military organization

By 1987 changes in military organization indicated the importance Chinese leaders attached to structural reform in building military forces capable of waging modern, combined-arms warfare. These reforms included the creation of the state Central Military Commission parallel to the party Central Military Commission, reduction in force, reorganization of military regions, formation of group armies, enactment of the new Military Service Law, and reorganization of defense industries.

State and Party Central Military Commissions

At the apex of Chinese military organization stood two bodies—the state and party Central Military Commissions. The 1982 state Constitution created the state Central Military Commission as the state organ subordinate to the National People's Congress responsible for "directing the country's armed forces". The party Central Military Commission, elected by the party Central Committee, exercised de facto, authoritative policy-making and operational control over the military. In addition to the chairman, the party Central Military Commission in 1987 included a permanent vice chairman who was concurrently secretary general, two vice chairmen, and four deputy secretaries general. The leadership of the state and party Central Military Commissions was identical, but the membership of the party Central Military Commission below the top leadership was thought to include regional commanders and service chiefs.

Ministry of National Defense and NDSTIC

Beneath the two Central Military Commissions were the Ministry of National Defense and the National Defense Science, Technology, and Industry Commission (NDSTIC), which separately took orders from the two Central Military Commissions but had no operational control over the PLA. The Ministry of National Defense was responsible for military modernization and provided administrative support for the PLA. It was responsible for planning, manpower, budget, foreign liaison, and training materials, but it possessed no policy-making or implementation authority. The NDSTIC—formed in August 1982 by merging the National Defense Science and Technology Commission, National Defense Industries Office, and Office of the Science, Technology, and Armaments Commission of the party Central Military Commission—was responsible for military research and development, weapons procurement, and coordination of the defense and civilian economic sectors.

Operational control

In 1987 operational control of the PLA ran from the two Central Military Commissions to the PLA's three general departments: General Staff Department, General Political Department, and General Logistics Department. Below the department level ran parallel chains of command for operational, political, and logistical matters, each with its own separate communications facilities. Military policy originated in the party Political Bureau or the party Central Military Commission, became an operational order at the General Staff Department level, flowed through the military regions, and arrived at a main-force unit. Orders to regional forces also passed through the military district (provincial) level.

General Staff Department

The General Staff Department carried out staff and operational functions for the PLA and had major responsibility for implementing military modernization plans. Headed by the chief of general staff, the department served as the headquarters for the ground forces and contained directorates for the three other armed services: Air Force, Navy, and Strategic Missile Force. The General Staff Department included functionally organized subdepartments for artillery, armored units, engineering, operations, training, intelligence, mobilization, surveying, communications, quartermaster services, and politics. Navy Headquarters controlled the North Sea Fleet, East Sea Fleet, and South Sea Fleet. Air Force Headquarters generally exercised control through the commanders of the seven military regions. Nuclear forces were directly subordinate to the General Staff Department. Conventional main, regional, and militia units were controlled administratively by the military region commanders, but the General Staff Department in Beijing could assume direct operational control of any main-force unit at will. Thus, broadly speaking, the General Staff Department exercised operational control of the main forces, and the military region commanders controlled the regional forces and, indirectly, the militia.

General Political Department

The General Political Department was responsible for ideological indoctrination, political loyalty, morale, personnel records, cultural activities, discipline, and military justice, and it provided the party structure for the PLA. It also published Jiefangjun Bao (Liberation Army Daily), the PLA's influential newspaper. The General Political Department director was at the head of a system of political commissars assigned to each echelon in the PLA. One of the primary tasks of the political commissar was the supervision of the party organization through party committees at the battalion level and above or through party branches in companies. Virtually all high-ranking officers in the military were party members. Until the early 1980s, when party membership in the PLA was restricted, an effort was made to have a party or Communist Youth League member in every unit down to the smallest maneuver element. Political commissars were equal in rank and authority to the commander of their echelon in peacetime but theoretically deferred to the commander during war. Commissars assumed many time-consuming chores, such as personnel problems, relations with civilians, and troop entertainment.

General Logistics Department

The General Logistics Department, headed by a director, was responsible for production, supply, transportation, housing, pay, and medical services. Historically, much of this support came from the civilian populace, and before the establishment of the General Logistics Department it was organized most often by commissars. PLA logistical resources in 1980 were far fewer than those of Western or Soviet forces; in the event of war the Chinese military would be heavily dependent upon the militia and civilians. In 1985 the General Logistics Department was reorganized, its staff cut by 50 percent, and some of its facilities turned over to the civilian sector.

Streamlining and reduction in force

Efforts began in the 1980s to streamline the PLA and organize it into a modern fighting force. The first step in reducing the 4.5-million-member PLA in the early 1980s was to relieve the PLA of some of its nonmilitary duties. The Railway Engineering Corps and the Capital Construction Engineering Corps were civilianized, and in 1983 the PLA internal security and border patrol units were transferred to the People's Armed Police Force.

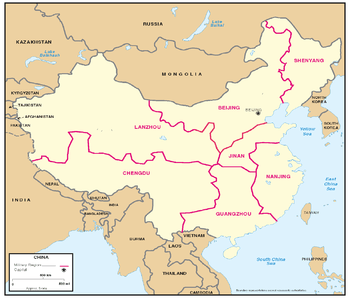

In 1985 China reorganized its 11 military regions into 7 and began a 2-year program to reduce the force by 1 million. Eight military regions were merged into four—Chengdu, Jinan, Lanzhou, and Nanjing—and three key regions—Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shenyang—remained intact. The PLA accomplished its 1-million-troop cut by streamlining the headquarters staffs of the three general departments, the military regions, and the military districts; reducing the size of the Air Force and the Navy; retiring older, undereducated, or incompetent officers; and transferring county- and city-level people's armed forces departments, which controlled the militia, to local civil authorities.

The PLA also reorganized its field armies (main-force armies) into group armies to increase its capability to wage combined-arms warfare. Breaking with the previously triangular organization of military units, the group armies combined formerly independent arms or services into a comprehensive combat unit. Group armies consisted of infantry and mechanized infantry divisions, tank divisions or brigades, and a number of artillery, antichemical, air defense, engineer, signal, reconnaissance, electronic countermeasure, and logistics troops. In the late 1980s, some group armies also had helicopter, air support, or naval units.

In 1987 PLA strength was about 3 million. Ground forces numbered about 2.1 million—the world's largest standing army; the Navy about 350,000—including those assigned to Naval Aviation, Coastal Defense Forces, and Marine Corps; the Air Force about 390,000; and the Strategic Missile Force about 100,000. The PLA was supported by an estimated 4.3 million basic (armed and trained) militia and 6 million ordinary (poorly armed and trained) militia. According to the 1984 Military Service Law, the militia, which was being combined with a newly developed reserve system, and the People's Armed Police Force also formed part of the Chinese armed forces. In 1986 reserve forces were included officially in the organizational system.

Doctrine, strategy, and tactics

From the early 1950s until the mid-1970s, people's war remained China's military doctrine. The PLA's force structure, however, which came to include nuclear weapons as well as artillery, combat aircraft, and tanks, did not reflect the concept of people's war. In the late 1970s, Chinese military leaders began to modify PLA doctrine, strategy, and tactics under the rubric of "people's war under modern conditions." This updated version of people's war lacked a systematic definition, but it permitted Chinese military leaders to pay tribute to Mao's military and revolutionary legacy while adapting military strategy and tactics to the needs of modern conventional and nuclear warfare. Elaborating on Mao's concept of active defense—tactically offensive action with a defensive strategy—Chinese strategy was designed to defeat a Soviet invasion before it could penetrate deeply into China. Chinese strategists envisaged a forward defense, that is, near the border, to prevent attack on Chinese cities and industrial facilities, particularly in north and northeast China. Such a defense-in-depth would require more positional warfare, much closer to the border, in the initial stages of a conflict. This strategy downplayed the people's war strategy of "luring in deep" in a protracted war, and it took into account the adaptations in strategy and tactics necessitated by technological advances in weaponry. The PLA emphasized military operations using modernized, combined arms tactics for the dual purpose of making the most effective use of current force structure and of preparing the armed forces for more advanced weaponry in the future.

The doctrine of "people's war under modern conditions" also incorporated the use of strategic and tactical nuclear weapons. China's own nuclear forces, which developed a second-strike capability in the early 1980s, provided Beijing with a credible, if minimum, deterrent against Soviet or United States nuclear attack. China repeatedly has vowed never to use nuclear weapons first, but it has promised retaliation against a nuclear attack. Chinese strategists also evinced an interest in tactical nuclear weapons, and the PLA has simulated battlefield use of such weapons in offensive and defensive exercises.

Education and training

Reforms in training and education constituted an important part of the military modernization program in the 1980s. Senior officials recognized that improving the military skills and raising the education levels of both officers and troops were necessary prerequisites for the utilization of more advanced weaponry and the conduct of combined-arms operations. The PLA leadership focused education reforms on the military academy system and altered training to emphasize the officer corps, mechanized warfare, and combined arms operations.

Revitalization of the military academy system

Beginning in 1978, the PLA began to revive the military academy system, which the Cultural Revolution had devastated. By 1984 the system had over 100 institutions and consisted of two kinds of schools: command schools and specialized technical training centers. The PLA increased funding for military education, incorporated the study of foreign military experiences into the curriculum, and expanded contacts with foreign military academies. The rejuvenation of the military academies highlighted the emphasis placed on officer training. The PLA stipulated that most new officers should be military academy graduates, set minimum education levels for all officers, and established special classes to help officers meet those standards. Education and military academy training thus became criteria for promotion, in addition to seniority, performance, and experience.

In 1986 the PLA introduced three measures that further strengthened the military academy system. First, at the top level the PLA's Military Academy, Political Academy, and Logistics Academy merged to form the National Defense University, China's senior military training and research institution. Second, a new, three-level training system for command officers was announced, whereby command officers would receive regular training at junior, middle, and higher military command academies. Third, noncommissioned officer (NCO) training entered the military academy system with the establishment of a naval academy for petty officers and an air force NCO academy and the creation of NCO classes in over forty ground force academies.

Training reforms

Before the military modernization program began, PLA training was highly politicized and emphasized single-unit infantry troop training. Training reforms started with the depoliticization of training, whereby troops spent 80 percent of their time on military activities and 20 percent on political training. The scope of training then changed to concentrate on training officers capable of directing combined-arms warfare. Improved military education in the rejuvenated military academies provided some of this officer training. In addition, large-scale combined-arms exercises, which served to raise officer capabilities in commanding and coordinating combined-arms operations under combat conditions, occurred on a regular basis. These exercises stressed defense against attacking tanks, paratroopers, and aircraft and on occasion involved the simulated use of tactical nuclear weapons. The PLA also began using simulation equipment in training and in 1985 held its first completely simulated combat exercise. In 1986 the PLA training system underwent further reforms that complemented changes in military organization. A combined-arms tactical training center was created for training the newly formed group armies (former field armies) on a rotational basis. The training center coordinated group army exercises and utilized laser devices and simulation equipment in its training. The PLA also established a systematic training program for new recruits, replacing the old system in which inductees received basic training in their units. Under the new system, before new recruits were assigned to PLA units, they completed four months of training by a training regiment attached to a group army. The training regiments also trained squad leaders.

Personnel

Defense modernization brought changes to military personnel policies and practices. Personnel reforms emphasized upgrading the quality of recruits, improving conditions of service, altering promotion practices to stress professional competence over seniority or political loyalty, and providing new uniforms and insignia. The 1984 Military Service Law codified some of the changes in personnel policies and set the stage for further changes, such as the restoration of ranks.

Recruitment

The Military Service Law provided the legal basis for conscription, and it combined compulsory and voluntary service. All citizens between eighteen and twenty-two, regardless of sex, nationality, profession, family background, religion, or level of education, were obliged to perform military service. Almost 10 million men reached conscription age each year, but the PLA chose less than 10 percent of those eligible. A very small number of women were inducted annually. In the 1980s the PLA attempted to upgrade the quality of its inductees by changing recruiting practices. The PLA previously drew its recruits from rural youth of politically acceptable families. But the Military Service Law, the introduction of rural reforms offering greater economic opportunities for rural youth, and the PLA's requirements for higher educational levels caused recruitment to draw more recruits from better educated urban youth. Officers were drawn from military academy graduates; enlisted men and women who completed officer training in officially designated institutions and passed officer fitness tests; graduates of universities and special technical secondary schools; and civilian cadres and technical personnel recruited by nonmilitary units in the PLA. As a result of the new conscription and officer recruitment practices, the level of education in the PLA was much higher than that of the general population.

Conditions of service

The Military Service Law stipulated changes in conditions of service. Compulsory terms of service were three years for the ground forces and four for the Air Force and Navy. Soldiers could elect another term of one or two years in the ground forces and one year in the Navy and Air Force. After completing five years of compulsory service, a soldier could switch to voluntary service and could serve an eight- to twelve-year term until the age of thirty five. The conscription law also made provisions for limited preferential treatment of service personnel and their families. However, military service was regarded by some as a hardship because of low pay, poor food, lowered marriage prospects, and difficulties in finding jobs after demobilization. To alleviate the unattractive aspects of military service and to help local economic development, the PLA instituted a program of dual-use training, whereby soldiers learned skills useful in civilian life in addition to military training.

Promotion

In the late 1970s, the PLA began altering its promotion practices to reflect the new emphasis on professional competence. Previously, there had been no retirement system in effect, and junior and field-grade officers had remained at their posts for many years with little opportunity for advancement. When promotion occurred, it was based on seniority, political rectitude, or a patron-client relationship. Officers advanced up a single chain of command, remaining in the same branch or service for life. In 1978 the PLA reinstituted the retirement system established by the 1955 Military Service Law and promulgated officer service regulations, which set retirement ages for military officers. Thus the PLA began a two-pronged effort to retire older officers and to promote younger, better educated, professionally competent officers. Older officers, including many over seventy years of age, were offered generous retirement packages as inducements to retire. The PLA also formulated new promotion standards that set minimum education levels for officers and emphasized education in military academies as a criterion for promotion. Officers below the age of forty had to acquire a secondary-school education by 1990 or face demotion. Furthermore, past promotion practices were to be discarded in favor of greater emphasis on formal training, higher education levels, and selection of more officers from technical and noncombat units. With the reduction in force begun in 1985, professional competence, education, and age became criteria for demobilization as well as promotion. By 1987 the PLA's promotion practices were based more on merit than they had been a decade earlier; nevertheless, political rectitude and guanxi (personal connections) continued to play an important role in promotion, and no centralized personnel system had been established.

Ranks, uniforms, and insignia

The 1984 Military Service Law also stipulated that military ranks would be reintroduced to the PLA. Military leaders justified the restoration of ranks as improving organization, discipline, and morale and facilitating coordinated operations among different arms and services, thus serving to modernize and regularize the military. The PLA's experience in the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese border war, in which the absence of ranks led to confusion on the battlefield, was another factor leading to the restoration of ranks. However, the rank system was not immediately implemented because "preparatory work" still needed to be done. Implementation was delayed by disputes in higher echelons in the PLA over who would receive what rank and by the long process of reducing the size of the military. In mid-1987 the PLA still had not restored its system of ranks. The ranks for officers reportedly were to be based on the 1955 rank system, which included one supreme marshal and ten marshals at the very top. Ground force and Air Force ranks were to be general of the army/general of the air force, general or colonel general, lieutenant general, major general, senior colonel, colonel, lieutenant colonel, major, senior captain, captain, first lieutenant, and second lieutenant. Naval officer ranks were to be admiral of the fleet, admiral, vice admiral, rear admiral, senior captain, captain, commander, lieutenant commander, captain lieutenant, lieutenant, lieutenant (junior grade), and ensign. The enlisted ranks, planned to be based on the 1955 pattern, were to be expanded.

Although the restoration of ranks was delayed, in 1985 PLA personnel were issued new uniforms and service insignia. Officers at and above regimental level wore woolen and blended woolen uniforms; officers at battalion level and below and soldiers wore cotton uniforms. All personnel wore visored military caps, new collar insignia, and shoulder boards. The cap emblem was round with a design of five stars and the ideographs bayi (August 1, the anniversary of the 1927 Nanchang Uprising) surrounded by wheat ears and cog wheels. Uniform colors were olive green for the ground forces; dark blue in winter, and a white jacket and dark blue trousers in summer for the Navy; and an olive green jacket and dark blue trousers for the Air Force. Officer jackets had epaulets and golden buttons with the five-star and August 1 design. Collar badges were red for the ground forces, black for the Navy, and blue for the Air Force. Personnel of the intraservice Strategic Missile Force wore distinctive patches but otherwise retained the uniform of their parent service. The new uniforms replaced the baggy, green fatigue uniforms that had made it hard to distinguish between officers and soldiers. The change in uniforms served the needs of military modernization by raising morale, strengthening discipline, and facilitating command and organization.

Defense industry and the economic role of the PLA

The transformation of China's defense establishment into a system capable of independently sustaining modern armed forces was one of the major goals of the military modernization program. In the late 1970s and 1980s, defense spending remained relatively constant despite the shift in resources in favor of overall economic development. Reforms focused on reorganizing the defense research-and-development and industrial base, more closely integrating civilian and military science and industry, and selectively utilizing foreign technology. China sold arms for hard currency to provide additional funds for defense industries. The PLA continued to play its role in economic development by participating in selective construction projects, providing dual-use training, and producing most of its food needs.

Military expenditures

In the 1980s Chinese statistics indicated that defense spending represented a decreasing percentage of government expenditures, falling from 16 percent in 1980 to 8.3 percent of the state budget in 1987. However, United States Department of Defense studies suggested that the published budget figures understated defense spending by about one-half. With the growth of the Chinese economy under the modernization program, defense spending also represented a smaller percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP) than previously. United States Central Intelligence Agency analysts estimated that defense expenditures in 1978 absorbed 8 to 10 percent of GDP; in 1986 United States Department of Defense analysts estimated that China's military expenses fell within the range of 6 to 8 percent of GDP. Comparison of indices of defense procurement spending and industrial production from 1971 to 1983 revealed that the former increased by 15 percent, whereas the latter rose by 170 percent. These studies indicated that Chinese leaders have indeed subordinated military modernization to economic development.

United States Department of Defense officials in 1986 estimated Chinese defense spending by resources and force categories for the 1967 to 1983 period. Roughly 50 percent of defense expenditures were for weapons, equipment, and new facilities; 35 percent for operating costs; and 15 percent for research, development, and testing and evaluation. By service, these costs broke down to 25 percent for the ground forces; 15 percent for the Navy; 15 percent for strategic air defenses; 5 percent for ballistic missile forces; 5 percent for tactical air forces; and about 35 percent for command, logistics, personnel, intelligence, medical care, administration, research, development, testing and evaluation, and other support. Beginning in the late 1970s, China devoted more resources to its Strategic Missile Force, indicating an effort to increase its strategic security while modernizing the economy, and to national command and support activities, reflecting an emphasis on modernization of the defense structure.

Military R&D and NDSTIC

The National Defense Science, Technology, and Industry Commission was the coordinating body for military research and development and industrial production. The NDSTIC reported to the party Central Military Commission's National Defense Industries Committee and the State Council's Leading Group for Science and Technology. The NDSTIC supervised weapons research and development, coordinated military production of defense industries, and controlled funding for weapons procurement. The establishment of the NDSTIC was a reform measure designed to break down the barriers between civilian and military research and development and industry. Military science and industry previously had been secretive, segregated, and privileged sectors, having material, financial, and personnel resources superior to those available to the civilian sector. The creation of the NDSTIC was one measure by which Chinese leaders hoped to facilitate the transfer of technology between the military and civilian sectors. The NDSTIC, in particular through its trading arm, China Xinshidai Corporation, coordinated procurement of foreign technology for military purposes.

Defense industry

Beginning in 1978, Chinese leaders set out to transform the defense industries, which had a huge excess capacity and were criticized for having a "golden rice bowl" (rich but always begging for more). To utilize this excess capacity better and to break down the barriers between military and civilian industry, the machine-building ministries were reorganized, and civilians were appointed to manage them. The civilianized, renamed ministries and their responsibilities consisted of the Ministry of Nuclear Industry—nuclear weapons; Ministry of Aeronautics—aircraft; Ministry of Electronics Industry—electronics; Ministry of Ordnance Industry—munitions and armaments; Ministry of Astronautics—ballistic missiles and space systems; and China State Shipbuilding Corporation—naval construction. In 1986 the Ministry of Machine Building, which produced civilian heavy machinery and industrial equipment, and the Ministry of Ordnance Industry were consolidated into the new State Machine-Building Industry Commission as a way to strengthen the unified management of the national machine-building and weapons enterprises. In 1987 little information was available about this new commission or its relationship to the NDSTIC or to the State Economic Commission, whose Defense Bureau coordinated the civilian production of the defense industry. Further changes in defense industry structure occurred in 1986 and 1987, when inland defense enterprises were either relocated closer to transportation links or cities, closed down, or transferred to local civilian control and production.

Weapons production

In 1987 China adopted a new contractual system for weapons research, development, and production. It was not clear from available information how this contract system would affect the role of the NDSTIC as the coordinating body for defense science and industry. Previously, the NDSTIC controlled procurement funding, reviewed proposals for weapons requirements funneled through the General Staff Department's Equipment Subdepartment, and coordinated with defense industries to produce the needed equipment. Under the new system, the state divided defense research and development funds into three categories: military equipment research, basic and applied sciences research, and unidentified technological services. The first type of appropriation went to military arms and services, which signed contracts with research institutes or enterprises to develop and manufacture the required weapons. The contract system involved the PLA, which had been removed to a large extent from such activities, in the development and manufacture of the weapons it would use. The second category of funds was devoted to basic research and applied science to help modernize the defense industry. The third category went to technological services necessary for research programs. This reform was another measure designed to integrate military and civilian industry by placing the military production of defense industries within the framework of the planned-commodity economy. The new system further sought to provide the military with better equipment at a minimum cost, to force the defense industry to upgrade weapons designs and improve production, to improve the management of weapons research and development through state application of economic levers, to promote cooperation between research institutes and factories, and to increase the decision-making powers of the enterprises.

Procurement of weapons and equipment represented 45 percent of the defense budget during the 1967 to 1983 period. This figure included 25 percent for aircraft, 15 percent for ground forces weapons, and about 10 percent each for naval and missile systems. China's military-industrial complex, the third largest in the world, produced a wide variety of weapons, including light arms and ammunition, armor, artillery, combat aircraft, fast-attack craft, frigates, destroyers, conventional and nuclear submarines, electronic equipment, tactical missiles, and ballistic missiles. With the notable exception of China's indigenously produced nuclear submarines, nuclear missiles, and satellites, most Chinese weaponry was based on Soviet designs of the 1950s and 1960s. Much of this equipment was obsolete or obsolescent, and beginning in the late 1970s China made great efforts to upgrade the equipment by changing indigenous design or by incorporating Western technology. The greatest weaknesses were in conventional arms, precision-guided munitions, electronic warfare, and command, control, communications, and intelligence. China attempted to address these weaknesses by focusing military research on electronics—essential to progress in the previously mentioned areas—and by selectively importing key systems or technologies.

The PLA is extensively modernizing the technological capabilities of its armed forces; The CJ-10 long-range cruise missile made its first public appearance during the military parade on the 60th Anniversary of the People's Republic of China as a part of the Second Artillery Corps' long range conventional and possible nuclear missile forces; the CJ-10 represents the next generation in rocket weapons technology in the PLA. A similar naval cruise missile, the YJ-62, was also revealed during the parade; the YJ-62 serves as the People's Liberation Army Navy's latest development into naval rocketry.

Role of foreign military technology

Following the withdrawal of Soviet aid and advisers in 1960, which in turn crippled the defense industry and weapons production for several years, China stressed self-reliance in developing its own weaponry. The acquisition of foreign military technology became a contentious issue at times, particularly in the 1970s, when Maoists stressed complete self-reliance and more moderate leaders wished to import some foreign technology. The signing of an agreement to coproduce Rolls Royce Spey engines in 1975 signaled the resolution of that debate in favor of selective importation. Beginning in 1977, Chinese military delegations traveled abroad, particularly to Western Europe and, in the 1980s, to the United States, to visit Western defense manufacturers and to inspect the state of the art in military equipment. Chinese representatives showed great interest in a wide variety of weapons systems, but they made few purchases of complete weapons systems, concentrating instead on acquisition of selective components, equipment, or technologies and on concluding coproduction agreements.

China's selective approach to acquiring foreign military technology stemmed from the limited funds available for military modernization and the desire of Chinese leaders to avoid dependence on any one supplier. The selective approach also reflected the knowledge that assimilation of foreign technology could present problems because of the low level of Chinese military technology and lack of qualified personnel. Finally, the leadership realized that China's past emphasis on modifying foreign weapons and on reverse engineering had greatly limited China's weapons development capacity. To overcome weapons deficiency in the short run and achieve indigenous military research, development, and production in the long run, China's leaders combined the selective import of weapons and technology with improved technical training of defense personnel and development of the civilian economy.

China primarily was interested in obtaining defensive weapons from abroad to correct the PLA's most critical weaknesses. These weapons and equipment included antitank and antiaircraft missiles, armor-piercing ammunition, helicopters, trucks, jeeps, automobiles, and tank fire-control systems, engines, and turrets for the ground forces; antiship missiles, air defense systems, antisubmarine warfare systems, and electronic countermeasures systems for the Navy; and avionics, including fire control and navigation systems, for the Air Force. Observers opined that the entire military needed improved command, control, communications, and intelligence equipment and computers for command and logistics.

Arms sales

China's entrance into the international arms market in the 1980s was closely related to reforms in the defense industry and the leadership's desire to acquire the foreign technology needed to modernize PLA weaponry. Before 1980 China provided arms to friendly Third World countries at concessionary prices (see Foreign relations of the People's Republic of China). Because China transferred arms based on ideological and foreign policy considerations, terms were generous. Around 1980 China decided to sell weapons for profit to absorb excess capacity in the defense industry, make defense enterprises more economically viable, and earn the foreign currency required to purchase foreign military technology. China continued to sell military hardware at generous terms to some of its traditional friends and weapons customers, such as Pakistan, North Korea, Egypt, Sudan, and Somalia. Hard-currency sales to Middle Eastern countries, however, particularly Iran and Iraq, accounted for the rapid increase in Chinese weapons sales in the 1980s. United States Arms Control and Disarmament Agency studies indicated that from 1979 to 1983 Chinese arms sales ranked eighth in the world, for a total of about US$3.5 billion, of which an estimated US$2.1 billion went to Middle Eastern countries. In 1979 arms sales accounted for 0.9 percent of total exports; in 1983 arms sales rose to 6.3 percent of total exports. By 1987 China had jumped to fifth place, ranking behind the United States, the Soviet Union, United Kingdom, and France.

In the 1980s the defense industry and the PLA established a number of trading corporations to sell Chinese military hardware and to acquire foreign technology. The most prominent of these corporations were the China Xinshidai Corporation, affiliated with the NDSTIC; China North Industries Corporation (commonly known as Norinco), affiliated with the State Machine-Building Industry Commission; China National Aero-Technology Import and Export Corporation (CATIC), affiliated with the Ministry of Aeronautics; Great Wall Industrial Corporation and China Precision Machinery Import and Export Corporation, both affiliated with the Ministry of Astronautics; China Electronics Import and Export Corporation, affiliated with the Ministry of Electronics Industry; China Shipbuilding Trading Corporation, affiliated with the China State Shipbuilding Corporation; and China Xinxing Corporation, affiliated with the PLA General Logistics Department. In 1984 these corporations began promoting Chinese weapons, actively seeking technology transfer and coproduction agreements with foreign defense companies at international defense exhibitions in 1984.

Civilian production

In late 1978 China initiated a policy of integrating civilian and military industry more closely in order to promote overall civilian economic development. This policy entailed civilianizing the machine-building ministries to make the defense industry more responsive to civilian control and needs; increasing defense industry production of civilian goods, particularly consumer goods; and transferring technology from the more advanced defense sector to the civilian sector of the economy. Production of civilian goods totaled 6.9 percent of total defense industry output in 1975. In 1980 it rose to 18 percent, and by 1985 it had jumped to 41.8 percent of total output. Chinese officials predicted that by 1990 about 80 percent of defense industry output would be civilian goods. The large excess capacity of the defense industry, resulting from declining orders from the PLA, made possible the rapid growth in civilian output. The defense industry manufactured a wide variety of goods for civilian use, including motor vehicles, optical equipment, television sets, electrical appliances, pharmaceuticals, and medical instruments and prostheses. Many of these products were consumer goods in high demand. For example, in 1985 the Ministry of Ordnance Industry manufactured 500,000 motorcycles, representing two-thirds of total motorcycle output, as well as 250,000 cameras, 450,000 bicycles, and 100,000 refrigerators.

Following the formulation of regulations and mechanisms for such transfers, defense industries began transferring technology to civilian industries on a large scale in the mid-1980s. Technology transfers provided defense enterprises with additional, lucrative sources of income and furnished civilian enterprises with a wide range of useful, advanced technology to modernize production. For example, the Ministry of Astronautics disseminated aerospace technology to light industry and to the petroleum, chemical engineering, machine-building, textile, communications, medical, and electronics industries.

Economic roles of the PLA

The PLA played a role in economic development practically from its inception. Beginning in the late 1930s and early 1940s, when the party was headquartered in Yan'an, the Red Army raised its own food. After 1949 the PLA became involved in economic reconstruction tasks—building railroads and factories, reclaiming wasteland, digging irrigation canals, establishing state farms, and participating in disaster relief operations. The PLA accepted its role as a force in economic construction and devoted segments of its structure, such as the Engineering Corps, Railway Engineering Corps, Capital Construction Engineering Corps, Signal Corps, and Production and Construction Corps, to building up the national infrastructure. However, PLA regional- and main-force units played a much smaller role in aiding the civilian economy.

This pattern continued into the 1980s. The PLA remained self-sufficient in food, participated in selective infrastructure development projects, and aided in disaster relief. From 1981 to 1985, the PLA contributed 110 million workdays to 44,500 construction projects, including the diversion of river water from the Luan He to Tianjin, construction of the Shengli oilfield in Shandong and the Huolinhe open-cut coal mine in Shaanxi, expansion of Zhanjiang port in Guangdong, and afforestation work involving the planting of 290 million trees.

The PLA contributed to economic development in two additional ways. First, in November 1984 the government decided to transfer some military facilities to civilian control or joint military-civilian use. These facilities included airfields, ports, docks, railroads, depots and warehouses, and recreational areas. The devolution of these facilities to civilian control helped to alleviate problems that plagued the civilian economy. Second, beginning in the late 1970s, the PLA operated a large-scale program of dual-use training, whereby PLA personnel learned skills useful to the growing economy. Under this program, officers and soldiers received military training and training in specialized skills, such as livestock breeding, cultivation, processing, construction, machine maintenance, repair of domestic appliances, motor vehicle repair, and driving. In 1986 the PLA trained more than 650,000 soldiers in 25,000 training courses at over 6,000 training centers. In early 1987 surveys indicated that over 70 percent of demobilized PLA personnel left the armed forces with skills they could use as civilians.

See also

- Revolution in Military Affairs

- Arms industry

- Technological and industrial history of the People's Republic of China

- People's Republic of China military reform

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.