Deendayal Upadhyaya

| Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of Bharatiya Jana Sangh | |

|

In office 1967–1968 | |

| Preceded by | Balraj Madhok |

| Succeeded by | Atal Bihari Vajpayee |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

25 September 1916 Nagla Chandrabhan, Mathura, British India (now Uttar Pradesh, India) |

| Died |

11 February 1968 (aged 51) Mughalsarai, Uttar Pradesh, India |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Political party | Bharatiya Jana Sangh |

| Alma mater | Birla Institute of Technology and Science |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Profession |

Philosopher Economist Sociologist Historian Journalist Political scientist |

| Religion | Hinduism |

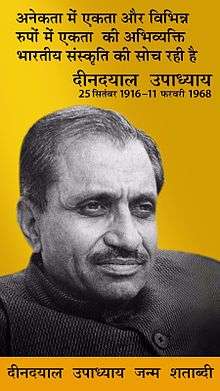

Pandit Deendayal Upadhyay (25 September 1916 – 11 February 1968) was an Indian philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and political scientist. He was one of the most important leaders of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, the forerunner of the present day Bharatiya Janata Party.

Early life and education

He was born in 1916 in the village Chandrabhan, now called Deendayal Dham, near the Farah town in Mathura District, 26 km away from Mathura. His father, Bhagwati Prasad, was a well known astrologer and his mother Shrimati Rampyari was a religious-minded lady. Both his parents died when he was young and he was brought up by his maternal uncle. He excelled academically under the guardianship of his maternal uncle and aunt. He went to high school in Sikar, Rajasthan where he matriculated. He stood first in the board exam, obtaining a Gold Medal from Maharaja Kalyan Singh of Sikar, along with a monthly scholarship of 10 rupees and an additional 250 rupees towards his books. He did Intermediate at the Birla College in Pilani, the predecessor of the present Birla Institute of Technology and Science. He did B. A. at the Sanatan Dharma College, Kanpur in 1939 and graduated in first division. He joined St. John's College, Agra to pursue a master's degree in English literature and got a gold medal. His maternal uncle persuaded him to sit for the Provincial Services Exam, where he got selected but declined to join the Services on account of his interest in working with the common man. He obtained a B.Ed and M.Ed degrees at Prayag and entered public service.[1]

RSS and Jana Sangh

While he was a student at Sanatan College, Kanpur in 1937, he came into contact with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) through his classmate Baluji Mahashabde. He met the founder of the RSS, K. B. Hedgewar, who engaged with him in an intellectual discussion at one of the shakhas. Sunder Singh Bhandari was also one of his classmates at Kanpur. This gave a fillip to his public life. He dedicated himself to full-time work in the RSS from 1942. He had attended the 40-day summer vacation RSS camp at Nagpur where he underwent training in Sangh Education. After completing second-year training in the RSS Education Wing, Upadhyaya became a lifelong pracharak of the RSS. He worked as the pracharak for the Lakhimpur district and, from 1955, as the joint prant pracharak (regional organiser) for Uttar Pradesh.

Deendayal Upadhyaya was a man of soaring idealism and had a tremendous capacity for organisation and reflected different aspects of a social thinker, economist, educationalist, politician, writer, journalist, speaker, organiser etc. He was regarded as an ideal swayamsevak of the RSS essentially because ‘his discourse reflected the pure thought-current of the Sangh’.[2]

He started a monthly Rashtra Dharma from Lucknow in the 1940s. The publication was meant for spreading the ideology of nationalism. Though he did not have his name printed as editor in any of the issues of this publication but there was hardly any issue which did not have his long lasting impression due to his thought provoking writings. Later he started a weekly Panchjanya and a daily Swadesh.[3]

In 1951, when Syama Prasad Mookerjee founded the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, Deendayal was seconded to the party by the RSS, tasked with moulding it into a genuine member of the Sangh Parivar. He was appointed as General Secretary of its Uttar Pradesh branch, and later the all-India General Secretary. The acumen and meticulousness shown by Deendayal deeply impressed Syama Prasad Mookerjee and elicited his famous remark:

| “ | If I had two Deendayals, I could transform the political face of India. | ” |

After Mookerjee's death in 1953, the entire burden of nurturing the orphaned organisation and building it up as a nationwide movement fell on the young shoulders of Deendayal. For 15 years, he remained the outfit's general secretary and built it up, brick by brick. He raised a band of dedicated workers imbued them with idealism and provided the entire ideological framework of the outfit. He also contested for Lok Sabha from Uttar Pradesh, but did not get elected.

Philosophy and social thought

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu politics |

|---|

|

|

Upadhyaya conceived the political philosophy Integral Humanism – the guiding philosophy of the Bharatiya Janata Party. The philosophy of Integral Humanism advocates the simultaneous and integrated program of the body, mind and intellect and soul of each human being. His philosophy of Integral Humanism, which is a synthesis of the material and the spiritual, the individual and the collective, bears eloquent testimony to this. In the field of politics and economics, he was pragmatic and down to earth. He visualised for India a decentralised polity and self-reliant economy with the village as the base.

Deendayal Upadhyay was convinced that India as an independent nation cannot rely upon Western concepts like individualism, democracy, socialism, communism or capitalism and was of the view that the Indian polity after Independence has been raised upon these superficial Western foundations and not rooted in what Upadhyay considered to be timeless traditions of India's ancient culture. He was of the view that the Indian intellect was getting suffocated by Western theories, which left a "roadblock" to the growth and expansion of original Bharatiya (Sanskrit: "of Bharat" [India]) thought. Upadhyay was compelled to answer what he felt was the urgent need in India for a "fresh breeze".

He welcomed modern technology but wanted it to be adapted to suit Indian requirements. Upadhyaya believed in a constructive approach. He exhorted his followers to co-operate with the government when it was right and fearlessly oppose it when it erred. He believed in Swaraj ("Self-governance") which was campaigned by the Bharathiya Janatha Party until the end of the last century. He died in unexpected circumstances and was found dead on 11 February 1968 at Mughal Sarai railway yard. Upadhyaya stated in the following address before thousands of delegates in Kozhikode :

| “ | We are pledged to the service not of any particular community or section but of the entire nation. Every countryman is blood of our blood and flesh of our flesh. We shall not rest till we are able to give to every one of them a sense of pride that they are children of Bharatmata. We shall make Mother India sujala, suphala ("overflowing with water and laden with fruits") in the real sense of these words. As Dashapraharana Dharini Durga with her ten weapons, she would be able to vanquish evil; as Lakshmi, she would be able to disburse prosperity all over and as Saraswati, she would dispel the gloom of ignorance and spread the radiance of knowledge all around her. With faith in ultimate victory, let us dedicate ourselves to this task. | ” |

Upadhyaya edited Panchjanya (Weekly) and Swadesh (Daily) from Lucknow. In Hindi, he has written a drama Chandragupta Maurya, and later wrote a biography of Shankaracharya. He translated a Marathi biography of Hedgewar, the founder of RSS.

He won awards and scholarships from the Maharaja of Sikar and industrialist Ghanashyam Das Birla. Turning down all offers of government and private sector employment, he joined the RSS. He kept company with Nanaji Deshmukh and Sundar Singh Bhandari, RSS pracharaks who went on to play a critical role in anti-Congress politics in the 1960s and 70s. Rising rapidly through the RSS ranks, he started a series of publications including its current mouthpiece, Panchjanya, and started another when this was banned. When that too, was suppressed, but he launched a third one. He served as its compositor, machine man and dispatcher and never missed an issue.

In a recent lecture, K. N. Govindacharya, who parted ways with the BJP under controversial circumstances, recalls how Upadhyaya expelled seven of the nine Jan Sangh MLAs in Rajasthan for opposing the Zamindari Abolition Act. He was capable of bold, principled decisions. At the same time, he was self-effacing, reluctant to hold office and ran the party by dint of moral authority over his workers. For all his dedication and commitment, he had a light touch and could laugh when shouldered aside by the self-important or rowdy. He washed his own clothes, wore his banians until they were tattered, had his hair cut by street barbers and could whip up a mean khichdi for a sick associate. While Deen Dayal was credited with a genius for organization, he proved to be the Sangh’s foremost thinker. He outlined his philosophy for governance to some 500 party workers in 1964 and presented an expanded version at its plenary session in 1965. The final version was delivered in the form of four lectures in Bombay, titled “Integral Humanism”. According to BJP veteran LK Advani, the title was chosen to contrast it with the thesis of ‘Radical Humanism’ put forward by MN Roy, the former Communist leader.

Integral Humanism was adopted by the BJS as its official doctrine and subsequently passed on to the BJP. The Sangh saw it as a home-grown, entirely indigenous economic and political philosophy that reconciled socialism and capitalism.

Subramanian Swamy, in his book Hindus Under Siege, explains: “IHT [Integral Humanism Theory] recognized that in a democratic market economy an individual has technical freedom of choice but the system without safeguards fails to accommodate the varying capabilities and endowments of a human being. Since the concept of survival of the fittest prevails in such a system, therefore some individuals achieve great personal advancement while others get trampled on or disabled in the ensuing rat race. We need to build a safety net into our policy for the underprivileged or disabled while simultaneously rewarding the meritorious or gifted. Otherwise, the politically empowered poor in a democracy who are in a majority will clash with the economically empowered rich who are the minority, thereby causing instability and upheaval in a market system.”

In a subsequent book, India and China, A Comparative Perspective, Swamy says IHT was the only alternative to Marxism and capitalism presented after 1947, but did not gain currency for political reasons. While capitalism suffers from the “one dimensional concept of the human pursuit of material progress”, IHT envisages a system that permits competitiveness while seeking adjusting complementaries, harmonizing material progress with spiritual advancement.

Advani devoted a chapter in his book My Country, My Life to his “political guru”, Deen Dayal Upadhyaya in which he says, “Deen Dayal-ji felt that both Capitalism and Communism were flawed philosophies...one considers man a mere selfish being hankering after money, having only one law, the law of fierce competition...whereas the other views him as a feeble lifeless cog in the whole scheme of things. The centralization of power, economic and political, is implied in both. They pit one section of society against the other, the individual against the collective, man against nature.” Integral Humanism, he adds, did not receive the attention that western political theories did. But it is “worthy of being placed alongside the works of Mahatma Gandhi and Dr Ram Manohar Lohia, with both of whom Deendayal-ji had so much in common.”

In the 1950s and 60s, Upadhyaya was lambasted for being right-wing and pro-capitalist, but insisted the BJS stood for a socialist economy, with a 1:20 ratio between the lowest and highest incomes and nationalization of infrastructure industries. Nehru, he said, was a socialist when it came to levying taxes but a capitalist when it came to amassing profits.

He certainly favoured economic freedom and opportunities for entrepreneurship, and criticized the government of the day for stifling avenues of investment. He had a horror of statist monopolies. On the other hand, he emphasized decentralization of the economy to empower local communities to make economic and developmental choices. He did not favour big business; he preferred the Gandhian ideal of large production from small units, “manufacture by the masses for the masses”.

He spoke of a “national sector”, a sort of public-private partnership that would facilitate self-employment and individual entrepreneurship. In brief, says Mahesh Chandra Sharma, who heads the Research and Development Foundation for Integral Humanism, Upadhyaya wanted economic freedom, along with the Right to Work. He wanted private ownership of the means of production but not centralization of ownership. In agriculture, he favoured land ownership and strongly opposed Soviet-style cooperatives, then a hot topic of discussion. Dr Mahesh Chandra Sharma’s book Economic Philosophy of Deen Dayal Upadhyaya quotes him as saying, “We should finish the unaccomplished task of land reforms and agricultural marketing.” Upadhyaya wanted self-reliance in foodgrains but warned against building up excessive buffer stocks that would distort the market – a tune many economists are singing in the wake of heavy procurement by the Food Corporation of India. Nor did he believe that government administered prices could combat inflation.

He was no admirer of the planning process and strongly critiqued all the Five-Year Plans for failing to focus on employment, infrastructure, agricultural production, education and public health. Upadhyaya spoke of appropriate technology as opposed to arbitrary mechanization, advocated sustainable consumption and set out principles of corporate ethics and social responsibility. Two of Upadhyaya’s acolytes sought to put his theories into practice. Dattopant Thengadi founded the Bharatiya Kisan Sangh and Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh, which went on to become the biggest trade union in the country. He also launched the Swadeshi Jagran Manch and famously turned down a Padma Bhushan from the Vajpayee government because he disapproved of its policies. Nanaji Deshmukh set up the Deen Dayal Research Institute, which created a model of rural development based on self-reliance. The fact that it boosted economic prosperity in the several hundred villages in Chitrakoot where it was applied attracts a great deal of attention from development agencies worldwide and drew fulsome praise from former President APJ Abdul Kalam. What about Upadhyaya’s political thought? Integral Humanism believes Dhamma is the guiding principle of the state. Dhamma is distinct from religion; it is the moral compass of government. He rejects statism and espouses liberal notions of individual liberty, within the parameters of social responsibility. His state was secular and unitary, albeit one in which power was decentralized. Upadhyaya accepted that western concepts of ‘nationalism, democracy, socialism, world peace and world unity’ were good ideals even though they did not appear to have worked well in practice. 11, 1968, Upadhyaya boarded the first-class coupe of the Sealdah-Pathankot Express from Lucknow, bound for Patna. His body was found lying parallel to the railway tracks outside Mughalserai station in the early hours of the morning. A commission was appointed to probe the murder and concluded that he had been pushed out of the compartment by unidentified thieves, struck his head against a traction pole and died. It was murder, but was it assassination? A currency note was found in the hand of Sri Upadhyaya which led to the conjecture that he might have tried to get down from the running train and died of trauma.

Recently, Madhya Pradesh BJP general secretary Arvind Menon kicked up a political storm by alleging that the Congress was indirectly responsible for Upadhyaya’s death. Congress leader Ajay Singh responded by challenging Menon to name the murderer. Singh pointed out that BJS leader Balraj Madhok, in his autobiography Zindagi Ka Safar had alleged that Atal Bihari Vajpayee exhorted him to float the accident theory about Upadhyaya's death and he was shunted out when he refused to do so. It was common knowledge, said Singh, that Vajpayee became the Bharatiya Jana Sangh president after Upadhyaya’s death.

Advani writes: “Till date, his murder has remained an unsolved mystery, although outwardly it appeared to have been a case of ordinary crime. The government accepted the demand of a group of MPs belonging to different political parties for a judicial enquiry, which was headed by Justice YV Chandrachud. The report he submitted, in which he said that he found no political angle to the murder and that it was a case of ordinary crime, satisfied no one.”

Nanaji Deshmukh punched holes in the Chandrachud commission’s findings. “Even the Sessions Judge of Varanasi disbelieved the CBI story that two petty thieves had murdered Punditji,” he wrote. The commission’s report did not explain why Upadhyaya was standing near the door of the bogie, or why he was clutching a Rs 5 note in his hand. Nor did it deal with the presence of a stranger in the bogie, which railway staff had testified to. The theft motive, too, was dubious because his suitcase and watch – the only items of value he was carrying – were untouched. The timing of the death, too, remains a mystery, with the state CID and CBI giving separate versions. The commission itself acknowledges that the symmetrical, neat manner in which the body was found did not argue death from a single impact with the traction pole. Govindacharya points out that the extent of injuries – his head had sustained a huge gash and his arms and legs were broken – also did not gel with the accident theory. Private investigations conducted at the time, he says, traced the killer to Nepal and identified him as a “Pathan”.

Had Upadhyaya survived, there’s little doubt he would have impacted the politics of India. He, rather than Vajpayee and Advani, would have steered the fortunes of the political right. Deshmukh played a critical role in the struggle against Emergency but retired from politics and left the field to the younger duo. Thengadi, who evinced no interest in politics, nonetheless made it clear that the NDA regime had strayed from the party’s principles. His BMS staged a rally against its economic policies and the SJM’s mouthpiece described them as “anti-national”. For all its lip service to Upadhyaya, the Vajpayee government made no attempt to propagate or apply his teachings. He remained unknown to the nation at large.

The Deen Dayal Research Institute is already a hub of frenetic activity as it deals with a flood of queries from government departments trying to familiarize themselves with Upadhyaya and his works.[4]

Death

He was assassinated on 11 February 1968 at Mughalsarai in UP, while travelling in a train.[5]

Legacy

Several institutions are named after him:

- Pt. Deendayal Upadhyay Shekhawati University, Sikar (Rajasthan)

- Pt. Deendayal Upadhyay Sanatan Dharma Vidyalaya, Kanpur

- Deen Dayal Upadhyay Gorakhpur University

- Deen Dayal Upadhyay Hospital, Delhi[6][7]

- Pandit Deendayal Upadhyay Vidyalaya, Kanpur

- Deen Dayal Upadhyaya College

- Pandit Deendayal Petroleum University, Gandhinagar, Gujarat.[8]

- Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya Medical College, Rajkot.[9]

- Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Hospital, Shimla, Himachal Pradesh.

- Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya Park, Indian Space Research Organisation Layout, Bengaluru, Karnataka 560078

See also

- Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana

- Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gram Jyoti Yojana

- Deen Dayal Antyoday Upchar Yojna

Notes

- ↑ Shekhar rawat (Resident of Deen Dayal Dham)

- ↑ Jaffrelot 2007, p. 140.

- ↑ "Deendayal Upadhyaya". Bharatiya Janata party. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ↑ https://in.news.yahoo.com/who-is-this-man-who-features-in-every-modi-speech-063715210.html

- ↑ "End of an Era". News Bharati. Retrieved 2014-09-28.

- ↑ Deendayal Upadhyaya hospital listing at Delhi Government web site

- ↑ "DOTS TB Centre".

- ↑ http://www.pdpu.ac.in

- ↑ "Medical Colleges". Medadmbjmc.in. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2007). Hindu Nationalism - A Reader. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-13097-3.