Declaration of war by the United States

A declaration of war is a formal declaration issued by a national government indicating that a state of war exists between that nation and another. The document Declarations of War and Authorizations for the Use of Military Force: Historical Background and Legal Implications gives an extensive listing and summary of statutes which are automatically engaged upon the US declaring war.

For the United States, Article One, Section Eight of the Constitution says "Congress shall have power to ... declare War". However, that passage provides no specific format for what form legislation must have in order to be considered a "declaration of war" nor does the Constitution itself use this term. Many have postulated "Declaration(s) of War" must contain that phrase as or within the title. Others oppose that reasoning. In the courts, the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, in Doe v. Bush, said: "[T]he text of the October Resolution itself spells out justifications for a war and frames itself as an 'authorization' of such a war."[1] in effect saying an authorization suffices for declaration and what some may view as a formal Congressional "Declaration of War" was not required by the Constitution.

This article will use the term "formal declaration of war" to mean Congressional legislation that uses the phrase "declaration of war" in the title. Elsewhere, this article will use the terms "authorized by Congress", "funded by Congress" or "undeclared war" to describe other such conflicts.

History

The United States has formally declared war against foreign nations five separate times, each upon prior request by the President of the United States. Four of those five declarations came after hostilities had begun.[2] James Madison reported that in the Federal Convention of 1787, the phrase "make war" was changed to "declare war" in order to leave to the Executive the power to repel sudden attacks but not to commence war without the explicit approval of Congress.[3] Debate continues as to the legal extent of the President's authority in this regard. Public opposition to American involvement in foreign wars, particularly during the 1930s, was expressed as support for a Constitutional Amendment that would require a national referendum on a declaration of war.[4] Several Constitutional Amendments, such as the Ludlow Amendment, have been proposed that would require a national referendum on a declaration of war.

After Congress repealed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in January 1971 and President Richard Nixon continued to wage war in Vietnam, Congress passed the War Powers Resolution (Pub.L. 93–148) over the veto of Nixon in an attempt to rein in some of the president's claimed powers. The War Powers Resolution proscribes the only power of the president to wage war which is recognized by Congress.

Declarations of war

Formal

The table below lists the five wars in which the United States has formally declared war against eleven foreign nations.[5] The only country against which the United States has declared war more than once is Germany, against which the United States has declared war twice (though a case could be made for Hungary as a successor state to Austria-Hungary).

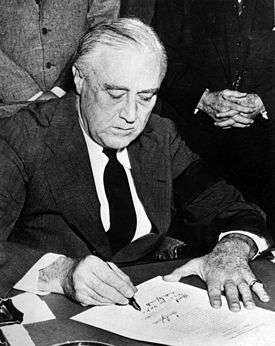

In World War II, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Germany and Italy, led respectively by Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, declared war on the United States, and the U.S. Congress responded in kind.[6][7]

Military engagements authorized by Congress

In other instances, the United States has engaged in extended military combat that was authorized by Congress.

| War or conflict | Opponent(s) | Initial authorization | Votes | President | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Senate | U.S. House | |||||

| Quasi-War | |

Act Further to Protect the Commerce of the United States July 9, 1798 |

18-4 | John Adams | Treaty of Mortefontaine | |

| First Barbary War | Tripoli | February 6, 1802[11] | Thomas Jefferson | War ended 1805 | ||

| Second Barbary War | Algiers | May 10, 1815[12] | James Madison | War ended 1816 | ||

| Enforcing 1808 slave trade ban; naval squadron sent to African waters to apprehend illegal slave traders | |

"Act in addition to the acts prohibiting the Slave Trade" 1819 | James Monroe | 1822 first African-American settlement founded in Liberia, 1823 U.S. Navy stops anti-trafficking patrols | ||

| Redress for attack on U.S. Navy's USS Water Witch | |

1858.[13] | James Buchanan | |||

| Occupation of Veracruz | |

H.J.R. 251, 38 Stat. 770 April 22, 1914 |

337–37 | Woodrow Wilson | Force withdrawn after six months. However, the Joint Resolution was likely used to authorize the Pancho Villa Expedition. In the Senate, "when word reached the Senate that the invasion had gone forward before the use-of-force resolution had been approved, Republicans reacted angrily" saying it was a violation of the Constitution, but eventually after the action had already started, a resolution was passed after the action to "justify" it since Senators did not think it was a declaration of war.[14][15] | |

| Intervention during the Russian Civil War | |

1918[16] | Woodrow Wilson | |||

| Lebanon crisis of 1958 | Lebanese opposition, led by |

H.J. Res. 117, Public Law 85-7, Joint Resolution "To promote peace and stability in the Middle East", March 9, 1957[17] | 72–19 | 355–61 | Dwight D. Eisenhower | U.S. forces withdrawn, October 25, 1958 |

| Vietnam War | |

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, August 7, 1964 | 88–2 | 416–0 | John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard M. Nixon | U.S. forces withdrawn under terms of the Paris Peace Accords signed January 27, 1973 |

| Multinational Force in Lebanon | Shia and Druze militias; Syria | S.J.R. 159 September 29, 1983 |

54–46 | 253–156 | Ronald W. Reagan | Forces withdrawn in 1984 |

| Persian Gulf War | |

H.R.J. Res. 77 January 12, 1991. |

52–47 | 250–183 | George H.W. Bush | The United Nations Security Council drew up terms for the cease-fire, April 3, 1991 |

| War in Afghanistan | |

S.J. Res. 23 September 14, 2001 |

98–0 | 420–1 | George W. Bush | Combat operations ended on December 28, 2014 |

| Iraq War[18] | |

H.J. Res. 114, March 3, 2003 |

77–23 | 296–132 | George W. Bush | Ba'athist Iraqi government deposed April 2003. U.S. combat operations ended August 31, 2010. War ended December 15, 2011. Destabilization of Iraq and emergence of ISIL in the region 2011–present.[19] |

Military engagements authorized by United Nations Security Council Resolutions and funded by Congress

In many instances, the United States has engaged in extended military engagements that were authorized by United Nations Security Council Resolutions and funded by appropriations from Congress.

| Military engagement | Opponent(s) | Initial authorization | President | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korean War | |

UNSCR 84, 1950 | Harry S. Truman | Korean Armistice Agreement,[20] 1953 |

| Multinational Force in Lebanon | Shia militias, Druze miltias, Syria | UNSCR 425, 1978

UNSCR 426, 1978 |

Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan | U.S. forces withdrew in 1984 |

| Persian Gulf War | |

UNSCR 678, 1990 | George H. W. Bush | UNSCR 689, 1991 |

| Bosnian War | |

UNSCR 770, 1992 UNSCR 776, 1992 UNSCR 836, 1993 |

Bill Clinton | Reflagged as IFOR in 1995, Reflagged as SFOR in 1996, Completed in 2004 |

| Second Liberian Civil War | Peacekeeping | UNSCR 1497, 2003 | George W. Bush | U.S. forces are withdrawn in 2003 after the UNMIL is established. |

| Haitian coup d'état | UNSCR 1529, 2004

UNSCR 1542, 2004 |

2004 | ||

| Libyan Civil War | |

UNSCR 1973, 2011 | Barack Obama | Debellation of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, October 31, 2011 |

Other undeclared wars

On at least 125 occasions, the President has acted without prior express military authorization from Congress.[21] These include instances in which the United States fought in the Philippine–American War from 1898–1903, in Nicaragua in 1927, as well as the NATO bombing campaign of Yugoslavia in 1999.

The United States' longest war was fought between approximately 1840 and 1886 against the Apache Nation. During that entire 46-year period, there was never more than 90 days of peace.

The Indian Wars comprise at least 28 conflicts and engagements. These localized conflicts, with Native Americans, began with European colonists coming to North America, long before the establishment of the United States. For the purpose of this discussion, the Indian Wars are defined as conflicts with the United States of America. They begin as one front in the American Revolutionary War in 1775 and had concluded by 1918. The United States Army still maintains a campaign streamer for Pine Ridge 1890–1891 despite opposition from certain Native American groups.[22]

The American Civil War was not an international conflict under the laws of war, because the Confederate States of America was not a government that had been granted full diplomatic recognition as a sovereign nation by other sovereign states.[23][24] The CSA was recognized by the United States government as a belligerent power, a different status of recognition that authorized Confederate warships to visit non-U.S. ports. This recognition of the CSA's status as a belligerent power did not impose any duty upon the United States to recognize the sovereignty of the Confederacy, and the United States never did so.

The War Powers Resolution

In 1973, following the withdrawal of most American troops from the Vietnam War, a debate emerged about the extent of presidential power in deploying troops without a declaration of war. A compromise in the debate was reached with the War Powers Resolution. This act clearly defined how many soldiers could be deployed by the President of the United States and for how long. It also required formal reports by the President to Congress regarding the status of such deployments, and limited the total amount of time that American forces could be deployed without a formal declaration of war.

Although the constitutionality of the act has never been tested, it is usually followed, most notably during the Grenada Conflict, the Panamanian Conflict, the Somalia Conflict, the Persian Gulf War, and the Iraq War. The only exception was President Clinton's use of U.S. troops in the 78-day NATO air campaign against Yugoslavia during the Kosovo War. In all other cases, the President asserted the constitutional authority to commit troops without the necessity of Congressional approval, but in each case the President received Congressional authorization that satisfied the provisions of the War Powers Act.

On March 21, 2011, a number of lawmakers expressed concern that the decision of President Barack Obama to order the U.S. military to join in attacks of Libyan air defenses and government forces exceeded his constitutional authority because the decision to authorize the attack was made without Congressional permission.[25] Obama explained his rationale in a two-page letter, stating that as commander in chief, he had constitutional authority to authorize the strikes, which would be limited in scope and duration, and necessary to prevent a humanitarian disaster in Libya.

See also

- Cold War

- Declaration of war by Canada

- Declaration of war by the United Kingdom

- Just War Theory

- Police action

- Timeline of United States military operations

- War on Terror

- War on Drugs

References

- ↑ "Doe v. Bush, 03-1266, (March 13, 2003)". FindLaw. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ Henderson, Phillip G. (2000). The presidency then and now. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-8476-9739-7.

- ↑ The Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 reported by James Madison : August 17,The Avalon Project, Yale Law School, retrieved Feb 13, 2008

- ↑ "Petition for a Constitutional Amendment to Hold National Referendums on Declarations of War from Danville, Ohio". The National Archives of the United States. 1938. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- ↑ Official Declarations of War by Congress

- ↑ BBC News, On This Day

- ↑ Whereas the Government of Germany has formally declared war against the government and the people of the United States of America... the state of war between the United States and the Government of Germany which has thus been thrust upon the United States is hereby formally declared. The War Resolution

- ↑ United States Congress (May 13, 1846). "An Act providing for the Prosecution of the existing War between the United States and the Republic of Mexico." (PDF). Government of the United States of America. Government of the United States of America. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 10, 2006. Retrieved August 10, 2006.

- 1 2 3 Declarations of War and Authorizations for the Use of Military Force: Historical Background and Legal Implications

- ↑ H.J.Res.169: Declaration of War with Austria-Hungary, WWI, United States Senate

- ↑ Key Events in the Presidency of Thomas Jefferson, Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia, (retrieved on August 10, 2010).

- ↑ Key Events in the Presidency of James Madison, Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia, (retrieved on August 10, 2010).

- ↑ Expenses - Paraguay Expedition, House of Representatives, 36th Congress, 1st Session, Mis. Doc. No. 86 (May 11, 1860), p. 142

- ↑ Cyrulik, John M., A Strategic Examination of the Punitive Expedition into Mexico, 1916-1917. Fort Leavenworth, KS, 2003. (Master's thesis)

- ↑ Wolfensberger, Don. Congress and Woodrow Wilson's Introductory Forays into Mexico, an Introductory Essay. Congress Project Seminar On Congress and U.S. Military Interventions Abroad. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Monday, May 17, 2004

- ↑ A History of Russia, 7th Edition, Nichlas V. Riasanovsky & Mark D. Steinberg, Oxford University Press, 2005.

- ↑ http://www.shafr.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/U.S.-Congress-Approval-of-the-Eisenhower-Doctrine-1957.pdf

- ↑ Obama's full speech: Operation Iraqi Freedom is Over, MSNBC

- ↑ Londoño, Ernesto (August 19, 2010). "Operation Iraqi Freedom ends as last combat soldiers leave Baghdad". The Washington Post.

- ↑ s:Korean Armistice Agreement

- ↑ The President's Constitutional Authority To Conduct Military Operations Against Terrorists and Nations Supporting Them

- ↑ Army Continues to Parade Wounded Knee Battle Streamer, National Congress of American Indians.

- ↑ "Preventing Diplomatic Recognition of the Confederacy, 1861–1865". U.S. Department of State.

- ↑ McPherson, James M. (2007). This Mighty Scourge: Perspectives on the Civil War. Oxford University Press US. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-19-531366-6.

- ↑ Obama Attacked for No Congressional Consent on Libya, New York Times.

Further reading

- Grotius, Hugo (2004). On The Law Of War And Peace. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4191-3875-1.

- Edwin Meese; Matthew Spalding; David F. Forte (2005). The Heritage guide to the Constitution. Regnery Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59698-001-3.

- Kenneth A. Schultz, Tying Hands and Washing Hands: The U.S. Congress and Multilateral Humanitarian Intervention, Ch. 4, pp 105–142, in Daniel Drezner, Ed. Locating the Proper Authorities: The Interaction of Domestic and International Institutions, University of Michigan Press, 2003.

External links

- The House of Rep, Republican Study Committee of War and Military Authorized Conflicts. 2003.

- Declarations of war and votes

- Text of Declaration of War on Japan

- Text of Declaration of War on Germany

- Text of Declaration of War on Bulgaria

- Authorization for Use of Military Force — signed September 18, 2001

- House Joint Resolution Authorizing Use of Force Against Iraq — signed October 16, 2002

- Instances of Use of United States Forces Abroad, 1798–1993

- A partial list of U.S. military interventions from 1890 to 2006

- U.S.-Africa Chronology