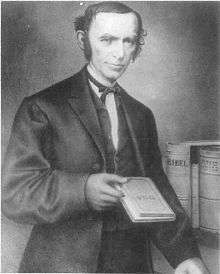

David Einhorn (rabbi)

| David Einhorn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

November 10, 1809 (2 Kislev 5570) Diespeck, Kingdom of Bavaria |

| Died |

November 2, 1879 (aged 69) (16 Cheshvan 5640) New York, New York, United States |

| Education | University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, University of Munich, University of Würzburg |

| Occupation | Reform rabbi |

| Parent(s) | Maier and Karoline Einhorn |

David Einhorn (November 10, 1809 – November 2, 1879) was a German rabbi and leader of Reform Judaism in the United States. Einhorn was chosen in 1855 as the first rabbi of the Har Sinai Congregation in Baltimore, the oldest congregation in the United States that has been affiliated with the Reform movement since its inception. While there he created an early American prayer book for the congregation that became one of the progenitors of the 1894 Union Prayer Book. In 1861, Einhorn was forced to flee to Philadelphia, where he became rabbi of Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel. He moved to New York City in 1866, where he became rabbi of Congregation Adath Israel.

Early years

He was born in Diespeck, Kingdom of Bavaria on November 10, 1809, to Maier and Karoline Einhorn. He was educated at the rabbinical school of Fürth, where he earned his rabbinical ordination at age 17.[1] He then studied at the universities of Erlangen, Munich and Würzburg, where he studied from 1828 to 1834, supported by his mother following the death of his father.[2]

Beliefs

He was a supporter of the principles of Abraham Geiger, and while still in Germany advocated the introduction of prayers in the vernacular German, the exclusion of nationalistic hopes[3] and the restoration of the Temple in Jerusalem and the sacrificial services there from the synagogue service, and other ritual modifications, lobbying on behalf of these changes at the 1844 Frankfurt Assembly.[1] He was chosen Landesrabbiner of the Birkenfeld at Hoppstädten, and afterward Landesrabbiner of Mecklenburg-Schwerin in 1847, succeeding Rabbi Samuel Holdheim whose views were a major influence on Einhorn.[1] An incident in which he blessed an uncircumcised boy, which upset many of his more traditional congregants, led to his departure from Germany.[1] He was called to Pest, Hungary in 1851 where his views met with such opposition that his temple was ordered closed only two months after his arrival there by the Emperor of Austria, who saw a connection between the Jewish reform movement and the Revolutions of 1848.[2]

Emigration

Einhorn emigrated to the United States and was named on September 29, 1855, as the first rabbi of the Har Sinai Congregation in Baltimore. In that role, Einhorn formulated the Olat Tamid siddur for use in services, which became one of the models for the Union Prayer Book published in 1894 by the Central Conference of American Rabbis.[4] Olat Tamid contrasted with Wise's Minhag America in particular by removing references to the status of Jews as a chosen people and eliminating references to the restoration of sacrificial services in the Temple.[1]

Reform Judaism

Einhorn was an opponent of the Cleveland Conference of 1855 and its decision that the Talmud had primacy in interpreting the Torah. In this stand, Einhorn stood in contrast to Rabbi Wise's efforts to find language that could accommodate the various strands of Judaism in the United States, arguing that such efforts betrayed the progress of reform.[1] Starting in 1856, he started publishing the German language magazine, Sinai, devoted to interests of radical reform, which he also used as a platform for his antislavery pronouncements. Einhorn remained an opponent of Interfaith marriage in Judaism, arguing in Sinai that such practices were "a nail in the coffin of the small Jewish race", though he opposed the retention of practices such as the wearing of phylacteries, the limitations on activity prohibited on Shabbat and kosher dietary laws, all of which he viewed as outmoded. Only those portions of the Torah that derived from a moral basis were to be retained.[1] He became the acknowledged leader of Reform Judaism in America.

Views on slavery

In 1861, Einhorn delivered a sermon as a response to a sermon by Morris Jacob Raphall that supported the existence of slavery, which Einhorn called a "deplorable farce" and argued that the institution of slavery in the South was inconsistent with Jewish values, noting the Jewish experience as slaves in Egypt as a reason that Jews should be more sensitive to the plight of slaves. He staunchly advocated this position, despite the fact that many of his congregants and colleagues were sympathetic to slavery in what was then a slave state. In his sermon titled War on Amalek, based on Exodus 17, Einhorn stated that "We are told that this crime [slavery] rests upon a historical right! ... Slavery is an institution sanctioned by the Bible, hence war against it is war against, and not for, God! It has ever been a strategy of the advocate of a bad cause to take refuge from the spirit of the Bible to its letter." A riot broke out in response to his sermon on April 19, 1861, in which the mob sought to tar and feather the rabbi.[1] Einhorn fled to Philadelphia where he became spiritual leader of Congregation Keneseth Israel.[1]

Retirement

In 1866 he moved to New York City, where he became the inaugural rabbi of Congregation Adas Jeshurun on 39th Street, which merged with Congregation Anshei Chesed in 1873 and adopted the new name Congregation Beth-El and built a new structure on 63rd Street. Einhorn retained the position as spiritual leader of the merged synagogue, delivering his final sermon on July 12, 1879, after which the congregation agreed to bestow upon him a pension of $3,500.[2] Upon his retirement, Einhorn was recognized by his fellow rabbis across denominations who held a farewell ceremony held at his apartment where he was presented with a resolution on behalf of the participants at the convention of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations that recognized Einhorn for his rabbinic service, noting the "ability and character which have marked his career, and the earnestness, honesty and zeal which have animated the heart of a man whom we proudly recognize as one of Israel's purest champions and noblest teachers."[5]

Death

Einhorn died at age 69 on November 2, 1879, at his home on East 64th Street of old age. He had become increasingly debilitated and was forced to stay in his room for some time.[2] His funeral was held before a packed house at Beth-El on November 6, 1879, where his plain coffin was carried into the congregation by 12 pallbearers and placed before the pulpit, which included such gathered rabbinic notables as Richard James Horatio Gottheil of Congregation Emanu-El, Einhorn's son-in-law and successor Kaufmann Kohler of Beth-El, another son-in-law Emil G. Hirsch of Louisville, Kentucky, along with representatives of the congregations he served in Baltimore and Philadelphia. He was buried at Green-Wood Cemetery.[6] Kaufmann Kohler carried on many of the efforts that Einhorn had initiated, collecting Einhorn's sermons and published them in book form, playing a major role in formulating the Pittsburgh Platform of 1885 and helped develop the Union Prayer Book using material that Einhorn had developed decades earlier in Olat Tamid.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Biography of David R. Einhorn, yourdictionary.com. Accessed August 29, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Staff. "DEATH OF THE REV. DAVID EINHORN.", The New York Times, November 3, 1879. Accessed August 30, 2010.

- ↑

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Einhorn, David". Encyclopædia Britannica. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 135.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Einhorn, David". Encyclopædia Britannica. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 135. - ↑ About Us: History, Har Sinai Congregation. Accessed August 29, 2010.

- ↑ Staff. "HONORS TO RABBI EINHORN.; PRESENTATION OF A TESTIMONIAL BY ORTHODOX AND REFORM MINISTERS.", The New York Times, July 14, 1879. Accessed August 30, 2010.

- ↑ Staff. "A JEWISH BURIAL SERVICE.; FUNERAL OF THE LATE RABBI EINHORN AT THE TEMPLE BETH-EL", The New York Times, November 7, 1879. Accessed August 30, 2010.

Sources

-

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Einhorn, David". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Einhorn, David". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

External links

- JewishEncyclopedia

- Abolitionist Rabbi David Einhorn Carte-de-Visite, circa 1855-1861 Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Highbeam entry

- The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 2003

- The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001

- David Einhorn: Das vom Judenthum gebotene Verhalten des Israeliten gegenüber seiner stiefväterlichen Behandlung von Seiten des Vaterlandes. Predigt, am 13. November 1847 in der Synagoge zu Schwerin gehalten Schwerin: Kürschner 1847 Original (German)

- Einhorn's reply to Raphall, condemning slavery