Dart's Elevator

Dart's Elevator was the world's first steam-powered grain elevator. It was designed and built by Joseph Dart and Robert Dunbar in 1842 in Buffalo, New York.[1][2] The elevator burned in the 1860s.

Description

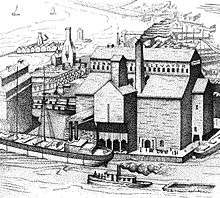

Designed and built in 1842 by Dart and Dunbar, the Dart Elevator in Buffalo, New York was 50 by 100 feet. It was the world's first steam-powered grain elevator.[3][4][5][6] It had a leather vertical conveyor belt with buckets.[7] This system could unload grain from the interiors of a lake boat hull, and do it far faster than the manual methods previously employed.[upper-alpha 1] The boat just had to be moored next to the storage elevator. Dunbar designed most of the grain elevators that at the end of the nineteenth century were along the Buffalo River. The city of Buffalo received grain from the states of Michigan and Illinois in volume in the 1830s. That presented the problem of congestion on the docks. The existing method of managing the transfer of grain from boats overwhelmed the port. Dart invented a mechanical system of belts with buckets attached to scoop up the grain from the hulls of boats and put into storage.[10]

Dart also devised a means of lowering the bottom end of the bucket into the holds of the large vessels that brought grain across the Great Lakes or of the barges that moved it along the Erie Canal. This was a turning point in the industry, marking a shift from the manual labor of men on ladders to a mechanized system. An important feature in Dart’s invention was the use of a rigid, nearly vertical frame to hold the bucket, chain, and sprocket assembly. This vertical assembly is contained in a building and referred to as the "marine tower" leg. This vertical conveyor assembly is housed in a wooden sleeve and could be leaned outward at the bottom of the elevator structure. It then is lowered directly into the interior of a vessel that had grain in its hold.[11]

Dart's elevator utilized a set of grain bins. On top of them was a cupola that had equipment for weighing. Incoming grain was taken to the top by the grain elevator vertical assembly and discharged by gravity to storage after being weighed. Then sold grain to be transferred was taken from the storage bins. It was elevated again to the cupola, weighed out and dispensed to a barge, train or grain carriage vehicle. The" marine leg" of the elevator was most important to these procedures and functions. Dart's innovations permitted the grain to be brought up with a set of scoop buckets attached to an endless loop belt. The elevator system undone and positioned the elevator leg in different forms. One was the "stiff leg" within the building which brought up grain into the grain elevator storage facilities from land based transports. Another was the "loose leg" brought up grain from ships and barges into the grain elevator building. The "loose leg" was kept in a raised position within the grain elevator building when not in use. That required an unusual tower above the cupola roof. When a ship's cargo of grain was to be unloaded the "loose leg" was lowered into the belly interior of the ship's hull.[10]

Dart's gain elevator set into place industrial principles of grain storage management. By the end of the nineteenth century these elevator systems had promoted a new style in architecture. The application of these grain transfer systems affected how storage buildings were designed and built. These elevator conveyor systems permitted the transfer of grain to bins separated by a distance, where before they had to be close to each other. The equipment that was designed with this new technology was more efficient and cost effective in management of grain. The layout of conveying equipment had an effect on the architecture of the elevator building. The classic high cupola grain storage building became typical. Many of the elevator companies incorporated these new innovations of Dart. Dart with engineer Dunbar applied state-of-the-art technology to the administration of grain. They applied their grain elevator innovations to boats and rail transportation that updated the old school methods of moving grain by hand to fit the greater needs of modern times.[10]

Dart's improved innovation of 1842 was an arrangement of buckets that were placed apart on a leather belt by a couple of feet. The bucket mechanism was taken out of the warehouse building and into the interior of a vessel holding grain. This mechanism was called a "marine leg." Dart further improved the system to where the buckets were put sixteen inches apart. The elevator bucket mechanism operated up to 2,000 bushels an hour. That amount was equivalent to a crew of men working all day in ideal conditions.[12] Dart's grain elevator building was finished in late 1842 at a site where the Buffalo river and the Evans Ship Canal meet. His elevator was a successful enterprise from the start. The Bennett Elevator was later built at this property. Dart was often paid double his regular fee for emergency storage of grain from a farm.[13] The first vessel unloaded at Dart's elevator was the schooner Philadelphia which had 4,515 bushels of wheat.[11][14] The first cargo of corn unloaded was on 22 June 1843 from the schooner South America.[5] Dart's elevator unloaded during the first year of operation over 200,000 bushels of grain.[15]

This early mechanization displaced the backs of Irish workers, who on a good day could manually carry "not more than 2,000 bushels a day" from the ship's hold.[9]

The invention had a profound effect on Buffalo and the movement of grains on the Great Lakes. The technology had worldwide application:

"The grain elevator developed as a mechanical solution to the problem of raising grain from the lake boats to bulk storage bins where it remained until being lowered for shipment on canal boats or railroad car. Less than fifteen years after Joseph Dart's invention of the grain elevator, Buffalo had become the world's largest grain port, surpassing Odessa, Russia; London, England; and Rotterdam, Holland."[16]

Demise

Dart's Elevator burned down around 1862 or 1863. Bennett Elevator was built at the same place in 1864. Dunbar was involved in the design of this new grain elevator also.[17]

References

Notes

- ↑ "The innovation was an immediate success. The schooner, John S. Skinner, came in from Milan, Ohio and docked in the early afternoon. She was unloaded by Dart's system, took on a ballast of salt, and was out of the harbor before dark. She was able to make a return trip to Milan and transfer her second cargo at Buffalo before other ships, being emptied by the hand method, had finished unloading their first cargoes. The grain trade, with this automatic aid, was to advance Buffalo to the position of the leading grain center in America."[8][9]

Citations

- ↑ Maio, Mark. "Grain Elevators: A History". The Buffalo & Erie County Historical Society. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- ↑ Baxter 1980.

- ↑ Hall 1896, p. 265.

- ↑ Green, H.J. (1888). "Buffalo's First Elevators and Mills". The Northwestern Miller. Miller Publishing Company. 26: 437. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

To Joseph Dart is due the honor of erecting the first steam storage and transfer elevator in the world.

- 1 2 Kane 1997, p. 4.

- ↑ Mingus 2003, p. 43.

- ↑ Jerome 2010, p. xv.

- ↑ Holder 2013, pp. 5–6.

- 1 2 LaChiusa 2014.

- 1 2 3 Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service,

U.S. Department of The Interior (1954), BUFFALO GRAIN ELEVATORS (PDF), Library of Congress, retrieved October 1, 2015 line feed character in

|first=at position 23 (help) - 1 2 Malloy, Jerry M. "Dart Street in Buffalo; So Who Was Dart?". The Buffalo History Gazette. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ↑ "IHS Built Environment Typology : Structures : Buildings : Grain Elevators".

- ↑ Smith 1884, p. 215.

- ↑ Dixon 2008, p. 264.

- ↑ Smith 1884, p. 216.

- ↑ "Nomination – Great Northern Grain Elevator 250 Ganson Street, Buffalo, NY". Buffalo Preservation Board. April 10, 2010. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- ↑ Smith 1884, p. 219.

Sources

- Baxter, Henry H. (1980). Grain Elevators. Adventures in Western New York History. 26. Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society. ASIN B0006EAECY.

- Dixon, Laurinda S. (2008). Twenty-first-century Perspectives on Nineteenth-century Art: Essays in Honor of Gabriel P. Weisberg. Associated University Presses. ISBN 978-0-87413-011-9.

- Hall, Henry (1896). America's Successful Men of Affairs: The United States at large. New York Tribune.

Settling then in Buffalo, N. Y., he invented flour mills, and designed and built there the first grain elevator in the world, becoming the father of the present system of handling and stowing grain.

- Holder, Robert (August 2013). The Beginnings of Buffalo Industry (PDF). pp. 5–6.

- Jerome, Kate Boehm (2010). Buffalo, NY: Cool Stuff Every Kid Should Know. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-0069-6.

- Kane, Joseph Nathan (1997). Famous First Facts, Fifth Edition. The H. W. Wilson Company. ISBN 0-8242-0930-3.

The first grain elevator operated by steam to transfer and store grain for commercial purposes was designed by Robert Dunbar and made by Jewett and Root for Joseph Dart, Buffalo, NY, in 1842. The first cargo of corn was unloaded on June 22, 1843, from the South America.

- LaChiusa, Chuck (2014). "History of Buffalo – Joseph Dart". Center for the Study of Art, Architecture, History and Nature. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- Mingus, Nancy Blumenstalk (2003). Buffalo: Good Neighbors, Great Architecture. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-2449-8.

- Smith, Henry Perry (1884). History of the City of Buffalo and Erie County: With ... Biographical Sketches of Some of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers ... D. Mason & Company.

External links

- Behrens, Scott Derek. "Thesis: From Grain to Waste: Repurposing Buffalo's Grain Elevators" (PDF). Retrieved October 1, 2015.

In 1842, Dart built the first steam-powered grain elevator

- "The First Grain Elevator: Early Grain Elevators". The Industrial Heritage Trail. Historical Marker Project. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

It was during this time that Buffalo entrepreneur Joseph Dart and engineer Robert Dunbar constructed the first steam-powered grain elevator and storage warehouse in the world.