Damsel in distress

The damsel in distress or persecuted maiden is a classic theme in world literature, art, film and video games. She is usually a beautiful young woman placed in a dire predicament by a villain or monster and who requires a male hero to achieve her rescue. After rescuing her, the hero often obtains her hand in marriage. She has become a stock character of fiction, particularly of melodrama. Though she is usually human, she can also be of any other species, including fictional or folkloric species; and even divine figures such as an angel, spirit, or deity.

The word "damsel" derives from the French demoiselle, meaning "young lady", and the term "damsel in distress" in turn is a translation of the French demoiselle en détresse. It is an archaic term not used in modern English except for effect or in expressions such as this. It can be traced back to the knight-errant of Medieval songs and tales, who regarded protection of women as an essential part of their chivalric code which includes a notion of honour and nobility.[1]

History

Ancient history

The damsel in distress theme featured in the stories of the ancient Greeks. Greek mythology, while featuring a large retinue of competent goddesses, also contains helpless maidens threatened with sacrifice. For example, Andromeda's mother offended Poseidon, who sent a beast to ravage the land. To appease him Andromeda's parents fastened her to a rock in the sea. The hero Perseus slew the beast, saving Andromeda. Andromeda in her plight, chained naked to a rock, became a favorite theme of later painters. This theme of the Princess and dragon is also pursued in the myth of St George.

Another early example of a damsel in distress is Sita in the ancient Indian epic Ramayana. In the epic, Sita is kidnapped by the villain Ravana and taken to Lanka. Her husband Rama goes on a quest to rescue her, with the help of the monkey-god Hanuman.

Jewish literature is replete with allusions to the Jewish people as the King's (i.e. God's) daughter. Rabbi Nathan of Breslov wrote an exposition of this theme and its place in Kabbalah and Judaism in second introduction to Tales of Rabbi Nachman, where he also explains the first tale, which is precisely the tale of The Lost Princess. Furthermore, the first introduction explains that in worldly stories there are hidden these concepts, albeit in spoiled or befuddled states, thus attributing such stories to veiled manifestations of such central Kabbalistic themes as redemption, the tzaddik, the Messiah, etc.

Post-classical history

European fairy tales frequently feature damsels in distress. Evil witches trapped Rapunzel in a tower, cursed the princess to die in "Snow White", and put Sleeping Beauty into a magical sleep. In all of these, a valorous prince comes to the maiden's aid, saves her, and marries her (though Rapunzel is not directly saved by the prince, but instead saves him from blindness after her exile).

A number of tales in the One Thousand and One Nights (Arabian Nights) also feature damsels in distress. A particularly influential Arabian Nights tale of this type was "The Ebony Horse", which revolves around the Arabian Prince, Qamar al-Aqmar, with the help of his flying mechanical horse, rescuing his lover, the Princess of Sana'a, from a Persian sage and then from the Byzantine Emperor. This story appears to have influenced later European tales such as Adenes Le Roi's Cleomades and "The Squire's Tale" told in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales.[2]

The damsel in distress was an archetypal character of medieval romances, where typically she was rescued from imprisonment in a tower of a castle by a knight-errant. Chaucer's The Clerk's Tale of the repeated trials and bizarre torments of patient Griselda was drawn from Petrarch. The Emprise de l'Escu vert à la Dame Blanche (founded 1399) was a chivalric order with the express purpose of protecting oppressed ladies.

The theme also entered the official hagiography of the Catholic Church – most famously in the story of Saint George who saved a princess from being devoured by a dragon. A late addition to the official account of this Saint's life, not attested in the several first centuries when he was venerated, it is nowadays the main act for which Saint George is remembered.

Obscure outside Norway is Hallvard Vebjørnsson, the Patron Saint of Oslo, recognised as a martyr after being killed while valiantly trying to defend a woman – most likely a slave – from three men accusing her of theft.

Modern history

17th century

In the 17th century English ballad The Spanish Lady (one of several English and Irish songs with that name), a Spanish lady captured by an English captain falls in love with her captor and begs him not to set her free but to take her with him to England, and in this appeal describes herself as "A lady in distress".[3]

18th century

The damsel in distress makes her debut in the modern novel as the title character of Samuel Richardson's Clarissa (1748), where she is menaced by the wicked seducer Lovelace.

Reprising her medieval role, the damsel in distress is a staple character of Gothic literature, where she is typically incarcerated in a castle or monastery and menaced by a sadistic nobleman, or members of the religious orders. Early examples in this genre include Matilda in Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto, Emily in Ann Radcliffe's The Mysteries of Udolpho, and Antonia in Matthew Lewis' The Monk.

The perils faced by this Gothic heroine were taken to an extreme by the Marquis de Sade in Justine, who exposed the erotic subtext which lay beneath the damsel-in-distress scenario.

One exploration of the theme of the persecuted maiden is the fate of Gretchen in Goethe's Faust. According to the philosopher Schopenhauer:

The great Goethe has given us a distinct and visible description of this denial of the will, brought about by great misfortune and by the despair of all deliverance, in his immortal masterpiece Faust, in the story of the sufferings of Gretchen. I know of no other description in poetry. It is a perfect specimen of the second path, which leads to the denial of the will not, like the first, through the mere knowledge of the suffering of the whole world which one acquires voluntarily, but through the excessive pain felt in one's own person. It is true that many tragedies bring their violently willing heroes ultimately to this point of complete resignation, and then the will-to-live and its phenomenon usually end at the same time. But no description known to me brings to us the essential point of that conversion so distinctly and so free from everything extraneous as the one mentioned in Faust (The World as Will and Representation, Vol. I, §68)

19th century

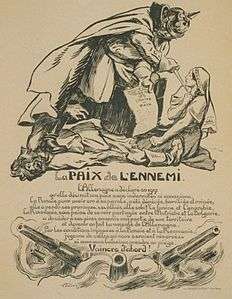

The misadventures of the damsel in distress of the Gothic continued in a somewhat caricatured form in Victorian melodrama. According to Michael Booth in his classic study English Melodrama the Victorian stage melodrama featured a limited number of stock characters: the hero, the villain, the heroine, an old man, an old woman, a comic man and a comic woman engaged in a sensational plot featuring themes of love and murder. Often the good but not very clever hero is duped by a scheming villain, who has eyes on the damsel in distress until fate intervenes to ensure the triumph of good over evil.[4]

Such melodrama influenced the fledgling cinema industry and led to damsels in distress being the subject of many early silent films, especially those that were made as multi-episode serials. Early examples include The Adventures of Kathlyn in 1913 and The Hazards of Helen, which ran from 1914 to 1917. The silent movie heroines frequently faced new perils provided by the industrial revolution and catering to the new medium's need for visual spectacle. Here we find the heroine tied to a railway track, burning buildings, and explosions. Sawmills were another stereotypical danger of the industrial age, as recorded in a popular song from a later era:

| “ | ... A bad gunslinger called Salty Sam was chasin' poor Sweet Sue He trapped her in the old sawmill and said with an evil laugh, |

” | |

| — Along Came Jones by The Coasters | |||

20th century

Another form of entertainment in which the damsel-in-distress emerged as a stereotype at this time was stage magic. Restraining attractive female assistants and imperiling them with blades and spikes became a staple of 20th century magicians' acts. Noted illusion designer and historian Jim Steinmeyer identifies the beginning of this phenomenon as coinciding with the introduction of the "sawing a woman in half" illusion. In 1921 magician P. T. Selbit became the first to present such an act to the public. Steinmeyer observes that: "Before Selbit's illusion, it was not a cliche that pretty ladies were teased and tortured by magicians. Since the days of Robert-Houdin, both men and women were used as the subjects for magic illusions". However, changes in fashion and great social upheavals during the first decades of the 20th century made Selbit's choice of "victim" both practical and popular. The trauma of war had helped to desensitise the public to violence and the emancipation of women had changed attitudes to them. Audiences were tiring of older, more genteel forms of magic. It took something shocking, such as the horrific productions of the Grand Guignol theatre, to cause a sensation in this age. Steinmeyer concludes that: "beyond practical concerns, the image of the woman in peril became a specific fashion in entertainment".[5]

The damsel-in-distress continued as a mainstay of the comics, film, and television industries throughout the 20th century. Imperiled heroines in need of rescue were a frequent occurrence in black-and-white film serials made by studios such as Columbia Pictures, Mascot Pictures, Republic Pictures, and Universal Studios, and in the 1930s, 40s and early 50s. These serials sometimes drew inspiration for their characters and plots from adventure novels and comic books. Notable examples include the character Nyoka the Jungle Girl, whom Edgar Rice Burroughs created for comic books and who was later adapted into a serial heroine in Republic productions such as Perils of Nyoka (1942). Additional classic damsels in that mold were Jane Porter, in both the novel and movie versions of Tarzan, and Ann Darrow, as played by Fay Wray in the movie King Kong (1933), in one of the most iconic instances. The notorious hoax documentary Ingagi (1930) also featured this idea, and Wray's role was repeated by Jessica Lange and Naomi Watts in remakes. As journalist Andrew Erish has noted: "Gorillas plus sexy women in peril equals enormous profits".[6] A small screen iconic portrayal, this time in children's cartoons, was Underdog's girlfriend, Sweet Polly Purebred.

Frequently cited examples of a damsel in distress in comics include Lois Lane, who was eternally getting into trouble and needing to be rescued by Superman, and Olive Oyl, who was in a near-constant state of kidnap, requiring her to be saved by Popeye.

The book Female Action Heroes described Princess Zelda as "perhaps one the most well-known 'damsel in distress' princesses in video game history".[7]

Critical and theoretical responses

Damsels in distress have been cited as an example of differential treatment of genders in literature, film, and works of art. Feminist criticism of art, film, and literature has often examined gender-oriented characterisation and plot, including the common "damsel in distress" trope.[8] Many modern writers, such as Angela Carter and Jane Yolen, have revisited classic fairy tales and "damsel in distress" stories or collected and anthologised stories and folk tales that break the "damsel in distress" pattern.[9] Often, such stories reverse the gender disparity by empowering the "damsel", or by placing boys or men in distress to be rescued thereby.

While late twentieth century feminist criticism may have highlighted alternatives to the damsel stereotype, the origins of some alternatives are to be found elsewhere. Joseph Campbell's work on comparative mythology has provided a theoretical model for heroes throughout the history of literature, drama, and film, which has been further developed by dramaturgical writers such as Christopher Vogler. These theories suggest that within the underlying story arc of every hero is found an episode known as the ordeal, where the character is almost destroyed. By surviving fear, danger, or torture the hero proves he or she has special qualities and ultimately emerges re-invented to progress to ultimate victory. Within this theory the empowered "damsel" can be a female hero rendered powerless and imperilled during her heroic ordeal but who ultimately emerges as a strong figure who claims victory; yet the male and female versions of such ordeal and empowerment still differ at a fundamental level, in that when there is a character doing the rescuing (sometimes referred to as "help unlooked for"), he is almost invariably male.

Examples can be found in films that date back to the early days of movie making. One of the films most often associated with the stereotype of the damsel in distress, The Perils of Pauline (1914), in fact provides at least a partial counterexample, in that Pauline, as played by Pearl White, is a strong character who decides against early marriage in favour of seeking adventure and becoming an author. Despite common belief, the film does not feature scenes with Pauline tied to a railroad track and threatened by a buzzsaw, although such scenes were incorporated into later re-creations and were also featured in other films made in the period around 1914. Academic Ben Singer has contested the idea that these "serial-queen melodramas" were male fantasies and has observed that they were marketed heavily at women.[10] The first motion picture serial made in the United States, What Happened to Mary? (1912), was released to coincide with a serial story of the same name published in McClure's Ladies' World magazine.

Empowered damsels were a feature of the serials made in the 1930s and 1940s by studios such as Republic Pictures. The "cliffhanger" scenes at the end of episodes provide many examples of female heroines bound and helpless and facing fiendish death traps. But those heroines, as played by actresses such as Linda Stirling and Kay Aldridge, were often strong, assertive women who ultimately played an active part in vanquishing the villains.

C.L. Moore's 1934 story "Shambleau" – generally acknowledged as epoch-making in the history of science fiction – begins in what seems a classical damsel in distress situation: the protagonist, space adventurer Northwest Smith, sees a "sweetly-made girl" pursued by a lynch mob intent on killing her and intervenes to save her, but finds her not a girl nor a human being at all, but a disguised alien creature, predatory and highly dangerous. Soon, Smith himself needs rescuing and barely escapes with his life.

These themes have received successive updates in modern-era characters, ranging from 'spy girls' of the 1960s to current movie and television heroines. In her book The Devil With James Bond (1967) Ann Boyd compared James Bond with an updating of the legend of St George and the "princess and dragon" genre, particularly with Dr. No's dragon tank. The damsel in distress theme is also very prominent in The Spy Who Loved Me, where the story is told in the first person by the young woman Vivienne Michel, who is threatened with imminent rape by thugs when Bond kills them and claims her as his reward.

The female spy Emma Peel in the 1960s British television series The Avengers was often seen in "damsel in distress" situations. The character and her reactions, as portrayed by actress Diana Rigg, differentiated these scenes from other movie and television scenarios where women were similarly imperilled as pure victims or pawns in the plot. A scene with Emma Peel bound and threatened with a death ray in the episode From Venus with Love is a direct parallel to James Bond's confrontation with a laser in the film Goldfinger.[11] Both are examples of the classic hero's ordeal as described by Campbell and Vogler. The serial heroines and Emma Peel are cited as providing inspiration for the creators of strong heroines in more recent times. Ranging from Joan Wilder in Romancing the Stone and Princess Leia in Star Wars to "post feminist" icons such as Buffy Summers from Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Sydney Bristow from Alias, Kim Possible from the series of the same name and Veronica Mars also from the series of the same name.[12][13][14]

Reflecting these changes, Daphne Blake of the Scooby-Doo cartoon series (who throughout the series is captured dozens of times, falls through trap doors, etc.) is portrayed in the Scooby-Doo film as a wisecracking feminist heroine (quote: "I've had it with this damsel in distress thing!"). The 2009 film Sherlock Holmes includes a classical damsel in distress episode, where Irene Adler (played by Rachel McAdams) is helplessly bound to a conveyor belt in an industrial slaughterhouse, and is saved from being sawn in half by a chainsaw; yet in other episodes of the same film Adler is strong and assertive – for example, overcoming with contemptuous ease two thugs who sought to rob her (and robbing them instead). In the film's climax it is Adler who saves the British Empire, dismantling at the last moment a device set to poison the entire membership of Parliament.

In the final scene of the 2007 Walt Disney Pictures film Enchanted the traditional roles are reversed when male protagonist Robert (Patrick Dempsey) is captured by Queen Narissa (Susan Sarandon) in her dragon form. In a King Kong fashion, she carries him to the top a New York skyscraper, until Robert's beloved Giselle climbs, sword in hand, to save him.

A similar role reversal is evident in Stieg Larsson's The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, in whose climatic scene the male protagonist is captured by a mass murderer, locked in an underground torture room, chained, stripped naked, and humiliated when his female partner enters to save him and destroy the villain. Still another example is Foxglove Summer, part of Ben Aaronovitch's Rivers of London series - where the protagonist Peter Grant is bound and taken captive by the Queen of the Faeries, and it is Grant's girlfriend who comes to rescue him, riding a Steel Horse.

In Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale The Snow Queen (1844), the protagonist Gerda, a little girl, rescues her friend Kay, a little boy, from the Snow Queen. In the 2013 film adaptation Frozen, Gerda and Kay are substituted with the sisters Anna and Elsa respectively.

See also

- Amy Rose

- Bella Swan

- Muriel Bagge

- Daphne Blake

- Femme fatale

- Feminist film theory

- Feminist literary criticism

- Feminist science fiction

- Final girl

- Ingenue

- Lily Bell

- Missing white woman syndrome

- Pearl White

- Portrayal of women in comics

- Portrayal of women in video games

- Predicament escape

- Princess and dragon

- Princess Daisy

- Princess Peach

- Princess Zelda

- Scream queen

- Target girl

- White Slavery

- Women in Refrigerators

References

- ↑ Johan Huizinga remarks in his book The Waning of the Middle Ages, "the source of the chivalrous idea, is pride aspiring to beauty, and formalised pride gives rise to a conception of honour, which is the pole of noble life". Huizinga, The Waning of the Middle Ages (1919) 1924:58.

- ↑ Ulrich Marzolph, Richard van Leeuwen, Hassan Wassouf (2004). The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 172–4. ISBN 1-57607-204-5.

- ↑ "Spanish Lady".

- ↑ Booth, Michael (1965). English Melodrama. Herbert Jenkins.

- ↑ Steinmeyer, Jim (2003). Hiding the Elephant: How Magicians Invented the Impossible. William Heinemann/Random House. pp. 277–295. ISBN 0-434-01325-0.

- ↑ Erish, Andrew (8 January 2006). "Illegitimate dad of 'Kong'; One of the Depression's highest-grossing films was an outrageous fabrication, a scandalous and suggestive gorilla epic that set box office records across the country". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Knight, Gladys L. (2010). Female Action Heroes: A Guide to Women in Comics, Video Games, Film, and Television. ABC-CLIO. p. 62. ISBN 0-313-37612-3.

- ↑ See, e.g., Alison Lurie, "Fairy Tale Liberation", The New York Review of Books, v. 15, n. 11 (Dec. 17, 1970) (germinal work in the field); Donald Haase, "Feminist Fairy-Tale Scholarship: A Critical Survey and Bibliography", Marvels & Tales: Journal of Fairy-Tale Studies v.14, n.1 (2000).

- ↑ See Jane Yolen, "This Book Is For You", Marvels & Tales, v. 14, n. 1 (2000) (essay); Yolen, Not One Damsel in Distress: World folktales for Strong Girls (anthology); Jack Zipes, Don't Bet on the Prince: Contemporary Fairy Tales in North America and England, Routledge: New York, 1986 (anthology).

- ↑ Singer, Ben (February 1999). Richard Abel, ed. Female Power in the Serial-Queen Melodrama: The Etiology of An Anomaly in Silent Film. Continuum International Publishing Group - Athlone. pp. 168–177. ISBN 0-485-30076-1.

- ↑ "Visitor Reviews: From Venus With Love". The Avengers Forever. Retrieved 2007-05-11.

- ↑ Jowett, Lorna (2005). Sex and The Slayer: A Gender Studies Primer for the Buffy Fan. Wesleyan University Press.

- ↑ Graham, Paula (2002). "Buffy Wars: The Next Generation". Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge. Bowling Green State University (4, Spring).

- ↑ Gough, Kerry (August 2004). "Active Heroines Study Day - John Moores University, Liverpool (in partnership with The Association for Research in Popular Fiction)". Scope - An Online Journal of Film and Television Studies. Institute of Film & Television Studies, University of Nottingham,.

Bibliography

- Mario Praz (1930) The Romantic Agony Chapter 3: 'The Shadow of the Divine Marquis'

- Robert K. Klepper, Silent Films, 1877-1996, A Critical Guide to 646 Movies, pub. McFarland & Company, ISBN 0-7864-2164-9