Rebecca West

| Dame Rebecca West | |

|---|---|

|

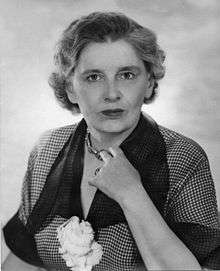

Portrait of Rebecca West by Madame Yevonde | |

| Born |

Cicely Isabel Fairfield 21 December 1892 Kerry, Ireland, United Kingdom (modern-day Ireland) |

| Died |

15 March 1983 (aged 90) London, United Kingdom |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | British |

| Children | Anthony West (1914–1987) |

Dame Cicely Isabel Fairfield DBE (21 December 1892 – 15 March 1983), known as Rebecca West, or Dame Rebecca West, was a British author, journalist, literary critic and travel writer. An author who wrote in many genres, West reviewed books for The Times, the New York Herald Tribune, the Sunday Telegraph, and the New Republic, and she was a correspondent for The Bookman. Her major works include Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941), on the history and culture of Yugoslavia; A Train of Powder (1955), her coverage of the Nuremberg trials, published originally in The New Yorker; The Meaning of Treason, later The New Meaning of Treason, a study of the trial of the British Fascist William Joyce and others; The Return of the Soldier, a modernist World War I novel; and the "Aubrey trilogy" of autobiographical novels, The Fountain Overflows, This Real Night, and Cousin Rosamund. Time called her "indisputably the world's number one woman writer" in 1947. She was made CBE in 1949,[1] and DBE in 1959,[2] in each case, the citation reads: "writer and literary critic".

Biography

Rebecca West was born Cicely Isabel Fairfield in 1892 in Kerry and grew up in a home full of intellectual stimulation, political debate, lively company, books and music.[3] Her mother, Isabella, a Scotswoman, was an accomplished pianist but did not pursue a musical career after her marriage to Charles Fairfield. Charles, an Anglo-Irish journalist of considerable reputation but financial incompetence, deserted his family when Cicely was eight years old. He never rejoined them and died impoverished and alone in a boarding house in Liverpool in 1906, when Cicely was 14.[4] The rest of the family moved to Edinburgh, Scotland, where Cicely was educated at George Watson's Ladies College. She had to leave school in 1907 due to a bout of tuberculosis.[5] Cicely did not have any formal schooling after the age of 16, due to lack of funds.

She had two older sisters. Letitia ("Lettie"), who was the best educated of the three, became one of the first fully qualified female doctors in Britain, as well as a barrister at the Inns of Court. Winifred ("Winnie"), the middle sister, married Norman Macleod, Principal Assistant Secretary in the Admiralty, and eventually director general of Greenwich Hospital. Winnie's two children, Alison and Norman, became closely involved in Rebecca's life as she got older;[6] Alison Macleod would achieve a literary career of her own.[7] West trained as an actress in London, taking the name "Rebecca West" from the rebellious young heroine in Rosmersholm by Henrik Ibsen. She and Lettie became involved in the women's suffrage movement, participating in street protests. Meanwhile, West worked as a journalist for the feminist weekly Freewoman and the Clarion, drumming up support for the suffragette cause.

In September 1912 West accused the famously libertine writer H. G. Wells of being "the Old Maid among novelists" in a provocative review in Freewoman of his novel Marriage. The review attracted Wells's interest and an invitation to lunch at his home. The two writers became lovers in late 1913.[8] Their 10-year affair produced a son, Anthony West, born on 4 August 1914; their friendship lasted until Wells's death in 1946.

West is also said to have had affairs with Charlie Chaplin and newspaper magnate Lord Beaverbrook.[9]

Early career

West established her reputation as a spokesperson for feminist and socialist causes and as a critic, turning out essays and reviews for The New Republic, New York Herald Tribune, New York American, New Statesman, The Daily Telegraph, and many more newspapers and magazines. George Bernard Shaw said in 1916 that "Rebecca West could handle a pen as brilliantly as ever I could and much more savagely."[10] During the 1920s, West began a lifelong habit of visits to the U.S. to give lectures, meet artists, and get involved in the political scene. There, she befriended CIA founder Allen Dulles, Charlie Chaplin, Harold Ross of The New Yorker, and historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., among many other significant figures of the day. Her lifelong fascination with the United States culminated in 1948 when President Truman presented her with the Women's Press Club Award for Journalism, calling her "the world's best reporter."[10]

In 1930, at the age of 37, she married a banker, Henry Maxwell Andrews, and they remained nominally together, despite one public affair just before his death in 1968.[11] West's writing brought her considerable wealth, and by 1940 she owned a Rolls Royce and a grand country estate, Ibstone House, in the Chiltern Hills of southern England. During World War II, West housed Yugoslav refugees in the spare rooms of her blacked-out manor, and she used the grounds as a small dairy farm and vegetable plot, agricultural pursuits that continued long after the war had ended.

Later life

As West grew older, she turned to broader political and social issues, including humankind's propensity to inflict violent injustice on itself. Before and during World War II, West traveled widely, collecting material for books on travel and politics. In 1936–38, she made three trips to Yugoslavia, a country she came to love, seeing it as the nexus of European history since the late Middle Ages. Her non-fiction masterpiece, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon is an amalgamation of her impressions from these trips. New York Times reviewer Katherine Woods wrote: "In two almost incredibly full-packed volumes one of the most gifted and searching of modern English novelists and critics has produced not only the magnification and intensification of the travel book form, but, one may say, its apotheosis." West was assigned by Ross' magazine to cover the Nuremberg Trials for The New Yorker, an experience she memorialized in the book A Train of Powder. In 1950 she was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[12] She also went to South Africa in 1960 to report on Apartheid in a series of articles for the Sunday Times.

She traveled extensively well into old age. In 1966 and 1969, she undertook two long journeys to Mexico, becoming fascinated by the indigenous culture of the country and its mestizo population. She stayed with actor Romney Brent in Mexico City and with Katherine (Kit) Wright, a long-time friend, in Cuernavaca.[13] She collected a large number of travel impressions and wrote tens of thousands of words for a "follow-up" volume to Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, tentatively titled "Survivors in Mexico." The work, however, was never finished, and only saw publication posthumously in 2003. Even into her late 70s, she visited Lebanon, Venice, Monte Carlo, and always went back to the United States.

Old age

Her husband became both sleepy and inattentive as he got older. The sleepiness led to a car accident where no one was hurt but Henry was charged with dangerous driving. He became obsessed by the Norwegian ballerina Gerd Larsen and he would refuse to travel with West but wanted to return to London to be with Larsen. West initially considered this to be purely her husband's infatuation, but she came to think that Larsen was driven by money. At her husband's funeral she had the upsetting problem of Larsen's request to be amongst the mourners, even though she had only known him for 18 months. Henry's will left £5,000 for Larsen.[11]

After her husband's death in 1968, West discovered that her husband had been unfaithful with other women.[11] She moved to London, where she bought a spacious apartment overlooking Hyde Park. Unfortunately, it was next door to the Iranian embassy. During the May 1980 incident, West, then 87, had to be evacuated.[14] In the last two decades of her life, West kept up a very active social life, making friends with Martha Gellhorn, Doris Lessing, Bernard Levin, comedian Frankie Howerd, and film star and director Warren Beatty, who filmed her for the movie Reds, a biography of journalist John Reed and his connection with the Russian Revolution. She also spent time with scholars such as Jane Marcus and Bonnie Kime Scott, who began to chronicle her feminist career and varied work.[15] She wrote at an unabated pace, penning masterful reviews for the Sunday Telegraph, publishing her last novel The Birds Fall Down (1966), and overseeing the film version of the story by BBC in 1978. The last work published in her lifetime was 1900 (1982). 1900 explored the last year of Queen Victoria's long reign, which was a watershed in many cultural and political respects.

At the same time, West worked on sequels to her autobiographically inspired novel The Fountain Overflows (1957); although she had written the equivalent of two more novels for the planned trilogy, she was never satisfied with the sequels and did not publish them. She also tinkered at great length with an autobiography, without coming to closure, and she started scores of stories without finishing them. Much of her work from the late phase of her life was published posthumously, including Family Memories (1987), This Real Night (1984), Cousin Rosamund (1985), The Only Poet (1992), and Survivors in Mexico (2003). Unfinished works from her early period, notably Sunflower (1986) and The Sentinel (2001) were also published after her death, so that her oeuvre was augmented by about one third by posthumous publications.

Relationship with her son

West's relationship with her son, Anthony West, was not a happy one. The rancor between them came to a head when Anthony, himself a gifted writer, his father's biographer (H. G. Wells: Aspects of a Life [1984]), and a novelist, published Heritage (1955), a fictionalized autobiography. West never forgave her son for depicting in Heritage the relationship between an illegitimate son and his two world-famous, unmarried parents, and for portraying the mother in unflattering terms. Essentially, she felt Anthony was airing in public his accusations against her as a bad mother, which stemmed partly from the fact that she had made a fiction of his provenance. She had asked him to call her Auntie, and his father Wellsie, until he was about four or five. He also felt she had made a habit of leaving him in institutions in his early years while she developed her career in the United States. West countered by claiming that she spent as much time with him as any child could reasonably hope to spend with a mother who was a professional. She was exasperated at his focus on her parenting, when he did not accuse his father of abandonment, even though Wells had been even more absent during Anthony's youth. Anthony, in fact, idolized Wells. The depiction of West's alter ego in Heritage as a deceitful, unloving actress (West had trained as an actress in her youth) and poor caregiver so wounded West that she broke off relations with her son and threatened to sue any publisher who would bring out Heritage in England. She successfully suppressed an English edition of the novel, which was only published there after her death, in 1984. Although there were temporary rapprochements between her and Anthony, a state of alienation persisted between them, causing West grief until her dying hour. She fretted about her son's absence from her deathbed, but when asked whether he should be sent for, answered: "perhaps not, if he hates me so much".[16]

Death

West suffered from failing eyesight and high blood pressure in the late 1970s, and she became increasingly frail. Her last months were mostly spent in bed, sometimes delirious, sometimes lucid, and she complained that she was dying too slowly.[16] She died on 15 March 1983 and is buried at Brookwood Cemetery, Woking.[17]

On hearing of her death, William Shawn, then editor in chief of The New Yorker, said:

| “ | Rebecca West was one of the giants and will have a lasting place in English literature. No one in this century wrote more dazzling prose, or had more wit, or looked at the intricacies of human character and the ways of the world more intelligently."[10] | ” |

Politics

West grew up in a home filled with discussions of world affairs. Her father was a journalist who often involved himself in controversial issues. He brought home Russian revolutionaries and other political activists, and their debates helped to form West's sensibility, which took shape in novels such as The Birds Fall Down, set in pre-revolution Russia.[18] But the crucial event that molded West's politics was the Dreyfus affair.[19] The impressionable Rebecca learned early on just how powerful was the will to persecute minorities and to subject individuals to unreasonable suspicion based on flimsy evidence and mass frenzy.[20] West had a keen understanding of the psychology of politics, how movements and causes could sustain themselves on the profound need to believe or disbelieve in a core of values—even when that core contradicted reality.[21]

It would seem that her father's ironic, sceptical temper so penetrated her sensibility that she could not regard any body of ideas as other than a starting point for argument. Although she was a militant feminist and active suffragette, and published a perceptive and admiring profile of Emmeline Pankhurst, West also criticized the tactics of Pankhurst's daughter, Christabel, and the sometimes doctrinaire aspects of the Pankhursts' Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).[22]

The first major test of West's political outlook was the Bolshevik Revolution. Many on the left saw it as the beginning of a new, better world, and the end of the crimes of capitalism. West regarded herself as a member of the left, having attending Fabian socialist summer schools as a girl. But to West, both the Revolution and the revolutionaries were suspect. Even before the Bolsheviks took power in October 1917, West expressed her doubts that events in Russia could serve as a model for socialists in Britain or anywhere else.[23]

West paid a heavy price for her cool reaction to the Russian Revolution; her positions increasingly isolated her. When Emma Goldman visited Britain in 1924 after seeing Bolshevik violence firsthand, West was exasperated that British intellectuals ignored Goldman's testimony and her warning against Bolshevik tyranny.[24]

For all her censures of Communism, however, West was hardly an uncritical supporter of the Western democracies. Thus in 1919–1920, she excoriated the U.S. government for deporting Goldman and for the infamous Palmer raids. She was also appalled at the failure of Western democracies to come to the aid of Republican Spain, and she gave money to the Republican cause.[25]

A staunch anti-Fascist, West attacked both the Conservative governments of her own country for appeasing Adolf Hitler and her colleagues on the left for their pacifism. Neither side, in her view, understood the evil Nazism posed. Unlike many on the left, she also distrusted Joseph Stalin. To West, Stalin had a criminal mentality that Communism facilitated.[26] She was outraged when the Allies switched their loyalties in regards to Yugoslav resistance movements by deciding in 1943 to start backing the Communist-led Partisans led by Tito in Yugoslavia, thus abandoning their support of Draža Mihailović's Chetniks whom she considered the legitimate Yugoslav resistance.[27] She expressed her feelings and opinions on the Allies' switch in Yugoslavia by writing the satirical short story titled "Madame Sara's Magic Crystal", but decided not to publish it upon discussion with Orme Sargent, Assistant Under-Secretary of State at the Foreign Office. Writing in her diary, West mentioned Sargent persuaded her that "the recognition of Tito was made by reason of British military necessities, and for no other reason" and following Sargent's claim, she described her decision not to publish the story as an expression of "personal willingness to sacrifice myself to the needs of my country".[28] After the war, West's anti-Communism hardened as she saw Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and other Eastern and Central European states succumb to Soviet domination.

It is not surprising in the context that West reacted to U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy differently from her colleagues. They saw a demagogue terrorizing liberals and leftists with baseless accusations of Communist conspiracy. West saw an oaf blundering into the minefield of Communist subversion. For her, McCarthy was right to pursue Communists with fervor, even if his methods were roughshod, though her mild reaction to McCarthy provoked powerful revulsion among those on the left and dismay even among anti-Communist liberals. She refused, however, to amend her views.[29]

Although West's anti-Communism earned the high regard of conservatives, she never considered herself one of them. In postwar Britain, West voted Labour and welcomed the Labour landslide of 1945. But she spoke out against domination of the Labour Party by British trade unions, and thought leftwing politicians such as Michael Foot unimpressive. She had mixed feelings about the Callaghan government. West admired Margaret Thatcher, not for Thatcher's policies, but for Thatcher's achievement in rising to the top of a male-dominated sphere.[30] She admired Thatcher's willingness to stand up to trade-union bullying.

In the end, West's anti-Communism remained the centerpiece of her politics because she so consistently challenged the Communists as legitimate foes of the status quo in capitalist countries. In West's view, Communism, like fascism, was merely a form of authoritarianism. Communists were under party discipline and therefore could never speak for themselves. And West was a supreme example of an intellectual who spoke for herself, no matter how her comments might injure her. Indeed, few writers explicitly acknowledged how much West's embrace of unpopular positions hurt her on the left. A whole generation of writers abandoned West and refused to read her, as Doris Lessing suggested.[31]

Religion

West's parents had her baptised into the Church of England two months after birth[32] and she considered herself a Christian, though an unconventional believer. At times, she found God to be wicked; at other times she considered Him merely ineffectual and defeated.[33] However, she revered Christ as the quintessentially good man,[34] she had great respect for the literary, pictorial, and architectural manifestations of the Christian ethos, and she considered faith a valid tool to grapple with the conundrums of life and the mysteries of the cosmos.[35] Although her writings are full of references to the Bible and ecclesiastical history, she was essentially anti-doctrinaire and occasionally blasphemous. In 1926 she expressed the unorthodox belief that "Christianity must be regarded not as a final revelation but as a phase of revelation."[36] Moreover, she rejected specific articles of belief such as the virgin birth, Original sin, the Atonement, and Providence. Her contribution to Virginia Woolf's Hogarth Letters Series, Letter to a Grandfather (1933), is a declaration of "my faith, which seems to some unfaith"[37] disguised as philosophical fiction. Written in the midst of the Great Depression, Letter to a Grandfather traces the progressive degeneration of the notion of Providence through the ages, concluding skeptically that "the redemptive power of divine grace no longer seemed credible, nor very respectable in the arbitrary performance that was claimed for it."[38] As for the Atonement, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon is in part meant as a refutation of that very doctrine, which she saw as having sparked a fatal obsession with sacrifice throughout the Christian era and, specifically, as having prompted Neville Chamberlain to formulate his policy of appeasement, which she vehemently opposed. She wrote

"All our Western thought is founded on this repulsive pretence that pain is the proper price of any good thing... [Augustine] developed a theory of the Atonement which was pure nonsense, yet had the power to convince... This monstrous theory supposes that God was angry with man for his sins and that He wanted to punish him for these, not in any way that might lead to his reformation, but simply by inflicting pain on him; and that He allowed Christ to suffer this pain instead of man and thereafter was willing on certain terms to treat man as if he had not committed these sins. This theory flouts reason at all points, for it is not possible that a just God should forgive people who are wicked because another person who was good endured agony by being nailed to a cross."[39]

World War II shocked her into a more conventional belief: "I believe if people are looking for the truth, the truth of the Christian religion will come out and meet them."[40] And in the early 1950s, she thought she had a mystical revelation in France and actively tried to convert to Catholicism.[41] There was a precedent in her family for this action, as her sister, Letitia, had earlier converted to Catholicism, thereby causing quite a stir. But West's attempt was short-lived, and she confessed to a friend: "I could not go on with being a Catholic... I don't want, I can't bear to, become a Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh, and I cannot believe that I am required to pay such a price for salvation."[42] Her writings of the 1960s and early 1970s again betray a profound mistrust towards God: "The case against religion is the responsibility of God for the sufferings of mankind, which makes it impossible to believe the good things said about Him in the Bible, and consequently to believe anything it says about Him."[43]

West's fluctuating attitude towards Christianity was offset by a more constant form of belief. She was informally a Manichaean all her life.[44] Although she was critical of Manichaeanism's puritanical excesses,[45] she did believe in dualism as the most fundamental working principle of the universe.[46] Although she conceded, optimistically, that "it is not possible to kill goodness,"[47] she also indulged in pessimistic statements like "natural man is mean,"[48] which is as much as saying that she adhered to the Manichaean belief that the essence of goodness was diffused inside gross matter like particles of light trapped in darkness. In accordance with this Manichaean skepticism, West wrote in a draft of her own memoirs: "I had almost no possibility of holding faith of any religious kind except a belief in a wholly and finally defeated God, a hypothesis which I now accept but tried for a long time to reject, I could not face it."[49]

Manichaean was also her lifelong struggle with the very question of how to deal with dualisms. At times she appears to favor the merging of opposites, for which Byzantium served as a model: "church and state, love and violence, life and death, were to be fused again as in Byzantium."[50] More dominant, however, was her tendency to view the tensions generated in the space between dualistic terms as life-sustaining and creative; hence, her aversion to homosexuality and her warning not to confuse the drive for feminist emancipation with the woman's desire to become like a man. Her insistence on the fundamental difference between men and women reveals her essentialism,[51] but it also bespeaks her innate Manichaean sensibility. She wanted respect and equal rights for women, but at the same time she required that women retain their specifically feminine qualities, notably an affinity with the life force: "Men have a disposition to violence; women have not. If one says that men are on the side of death, women on the side of life, one seems to be making an accusation against men. One is not doing that."[52] One reason why she does not want to make an accusation against men is that they are simply playing their assigned role in a flawed universe, which is, of course, the result of an imperfect deity. Only love can alleviate destructive aspects of the sex-antagonism: "I loathe the way the two cancers of sadism and masochism eat into the sexual life of humanity, so that the one lifts the lash and the other offers blood to the blow, and both are drunken with the beastly pleasure of misery and do not proceed with love's business of building a shelter from the cruelty of the universe."[53] In addition to the operations of love, female emancipation is crucial to removing the moral, professional, and social stigma associated with the notion of the "weaker sex," without trying to do away altogether with the temperamental and metaphysical aspects of the gender dualism itself. Thus, the "sex war" so graphically rendered in West's early short story "Indissoluble Matrimony" (1914) elevates the female character, Evadne, in the end because she accepts the terms of the contest without superficially trying to "win" that war.

Manichaeanism also informs West's political propensities. As Bernard Schweizer has argued: "St. Augustine and Schopenhauer emphasized the fallenness of human life, implying a quietistic stance that could be confused with conservatism, while the Reclus brothers [famous French anarchists] urged her to revolt against such pessimistic determinism. West's characteristically heroic personal and historic vision is a result of these two contending forces."[54] West's conviction that humanity will only fulfill its highest potentials if it adheres to the principle of process similarly arises from her Manichaean temperament: "Process is her most encompassing doctrine," states Peter Wolfe. "Reconciling her dualism, it captures the best aspects of the male and female principles."[55] In this way, West's Manichaean disposition infuses her religious sensibility, as well as her thinking about gender, politics, and art.

Cultural references

Virginia Woolf questioned Rebecca West being labelled as an "arrant feminist" because she offended men by saying they are snobs in chapter two of A Room of One's Own: "[W]hy was Miss West an arrant feminist for making a possibly true if uncomplimentary statement about the other sex?"

Bill Moyers's interview "A Visit With Dame Rebecca West," recorded in her London home when she was 89, was aired by PBS in July 1981. In a review of the interview, John O'Connor wrote that "Dame Rebecca emerges as a formidable presence. When she finds something or somebody disagreeable, the adjective suddenly becomes withering."[56]

West's first novel, The Return of the Soldier, was turned into a major motion picture in 1982, directed by Alan Bridges, starring Alan Bates, Glenda Jackson, and Julie Christie. More recently, an adaptation of The Return of the Soldier for the stage by Kelly Younger titled Once a Marine took West's theme of shell-shock-induced amnesia and applied it to a soldier returning from the war in Iraq with PTSD.

There have been two plays about Rebecca West produced since 2004. That Woman: Rebecca West Remembers, by Carl Rollyson, Helen Macleod, and Anne Bobby, is a one-woman monologue in which an actress playing Rebecca West recounts her life through some of her most famous articles, letters, and books. Tosca's Kiss, a 2006 play by Kenneth Jupp, retells West's experience covering the Nuremberg trials for The New Yorker.

Robert D. Kaplan's influential book Balkan Ghosts (1994) is an homage to West's Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941), which he calls "this century's greatest travel book"[57]

A 1990s female Canadian rock group headed by Alison Outhit called itself "Rebecca West."

In February 2006, BBC broadcast a radio version of West's novel The Fountain Overflows, dramatized by Robin Brook, in six 55-minute installments.

Bibliography

| Library resources about Rebecca West |

| By Rebecca West |

|---|

Fiction

- The Return of the Soldier (1918), the first World War I novel written by a woman, about a shell-shocked, amnesiac soldier returning from World War I in hopes of being reunited with his first love, a working-class woman, instead of continuing to live with his upper-class wife.

- The Judge (1922), a brooding, passionate novel combining Freudian Oedipal themes with suffragism and an existential take on cosmic absurdity.

- Harriet Hume (1929), a modernist story about a piano-playing prodigy and her obsessive lover, a corrupt politician.

- The Harsh Voice:Four Short Novels (1935), contains the short story "The Salt of the Earth," featuring Alice Pemberton, whose obsessive altruism becomes so smothering that her husband plots her murder. This was adapted for "The Alfred Hitchcock Hour" as "The Paragon" starring Joan Fontaine (season 2, episode 20) in 1963.[58] An additional story from the collection, "There is No Conversation" is the tale of a romance as told in hindsight by both parties, one a caddish Frenchman and the other a coarse American woman. This story was adapted for an hour-long radio drama in 1950 on NBC University Theatre and featured a commentary on West's story and writing skills by Katherine Anne Porter.

- The Thinking Reed (1936), a novel about the corrupting influence of wealth even on originally decent people. Perhaps a disguised self-critique of her own elegant lifestyle.

- The Fountain Overflows (1956), a semi-autobiographical novel weaving a fascinating cultural, historical, and psychological tapestry of the first decade of the 20th century, reflected through the prism of the gifted, eccentric Aubrey family.

- This Real Night (1984), sequel to The Fountain Overflows published posthumously

- Cousin Rosamund (1985), final, unfinished installment of the "Aubrey Trilogy" published posthumously[59]

- The Birds Fall Down (1966), spy thriller based on the deeds of the historical double agent Yevno Azef.[60]

- Sunflower (1986), published posthumously, about a tense love-relationship between an actress and a politician, reminiscent of West's relationship with H. G. Wells.

- The Sentinel (2002), edited by Kathryn Laing and published posthumously, West's very first extended piece of fiction, an unfinished novel about the suffragist struggle in Britain, including grim scenes of female incarceration and force-feeding.

Non-fiction

- Henry James (1916)

- The Strange Necessity: Essays and Reviews (1928), a blend of modernist literary criticism and cognitive science, including a long essay explaining why West disliked James Joyce's Ulysses, though she judged it an important book

- Ending in Earnest: A Literary Log (1931)

- Arnold Bennett Himself, John Day (1932)

- St. Augustine (1933), first psycho-biography of the Christian Church Father

- The Modern Rake's Progress (co-authored with cartoonist David Low) (1934)

- Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941), a 1,181-page classic of travel literature, giving an account of Balkan history and ethnography, and the significance of Nazism, structured around her trip to Yugoslavia in 1937

- The Meaning of Treason (1949)

- The New Meaning of Treason (1964)

- A Train of Powder (1955)

- The Court and the Castle: some treatments of a recurring theme (1958), excellent revisionist interpretations of literary classics, including Hamlet and Kafka's stories

- 1900 (1982), cultural history and fascinating "thick description" of this pivotal year

- The Young Rebecca (1982), West's early, radical journalism for The Freewoman and Clarion, edited by Jane Marcus

- Family Memories: An Autobiographical Journey (1987), West's autobiographical musings which remained unpublished during her life, assembled and edited by Faith Evans

- The Selected Letters of Rebecca West (2000), edited by Bonnie Kime Scott

- Survivors in Mexico[61] (2003), posthumous work about West's two trips to Mexico in 1966 and 1969, edited by Bernard Schweizer

- Woman as Artist and Thinker (2005), re-issues of some of West's best essays, together with her short-story "Parthenope"

- The Essential Rebecca West: Uncollected Prose (2010)[62]

Criticism and biography

- Wolfe, Peter (1 November 1971). Rebecca West: artist and thinker. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-0483-7.

- Deakin, Motley F. (1980). Rebecca West. Twayne Authors. Twayne. ISBN 978-0-8057-6788-9.

- Orel, Harold (1986). The literary achievement of Rebecca West. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-23672-7.

- Glendinning, Victoria (1987). Rebecca West: A Life. Knopf. ISBN 0394539354.

- Rollyson, Carl E. (1996). Rebecca West: a life. Scribner. ISBN 0684194309.

- Rollyson, Carl (March 2007) [1998]. The Literary Legacy of Rebecca West. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-43804-4.

- Norton, Ann V. (2000). Paradoxical Feminism: The Novels of Rebecca West. International Scholars Publications. ISBN 978-1-57309-392-7.

- Schweizer, Bernard (2002). Rebecca West: heroism, rebellion, and the female epic. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-32360-7.

- Rollyson, Carl (2005). Rebecca West and the God That Failed: Essays. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-36227-1.

- Schweizer, Bernard, ed. (2006). Rebecca West Today: Contemporary Critical Approaches. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 978-0-87413-950-1.

References

- ↑ The London Gazette, 3 June 1949, Supplement: 38628, p. 2804.

- ↑ The London Gazette, 30 December 1958, Supplement: 41589, p. 10.

- ↑ Glendinning 1987, p. 9

- ↑ Glendinning 1987, pp. 21–22

- ↑ Rollyson 1996, p. 29

- ↑ Rollyson 1996, pp. 418–27

- ↑ "Archives Hub". Archives Hub. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ↑ Gordon N. Ray, H.G. Wells & Rebecca West (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974), pp. 1–32.

- ↑ Rollyson 1996, pp. 100, 115

- 1 2 3 Linda Charlton, "Dame Rebecca West Dies in London, The New York Times, 16 March 1983.

- 1 2 3 Gibb, Lorna (2013). West's World: The Life and Times of Rebecca West. London: Macmillan. p. contents. ISBN 0230771491.

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter W" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ Rollyson 1996, pp. 353–9

- ↑ Rollyson 1996, pp. 413–4

- ↑ Jane Marcus, The Young Rebecca: Writings of Rebecca West 1911–17, Indiana University Press, 1982, p. x; Bonnie Kime Scott, Refiguring Modernism (Vol. 1), Indiana University Press, 1995, p. xli.

- 1 2 Rollyson 1996, p. 427

- ↑ "Rebecca West". Necropolis Notables. The Brookwood Cemetery Society. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- ↑ Schweizer 2006, Rollyson, Carl p. 10

- ↑ Rollyson 1996, p. 25

- ↑ Rollyson 1996, p. 286

- ↑ Rollyson 2005, pp. 51–52

- ↑ West, Rebecca (1982). Marcus, Jane, ed. The young Rebecca: writings of Rebecca West, 1911–17. Indiana University Press. pp. 108–110, 206–9, 243–62. ISBN 978-0-253-23101-7.

- ↑ Rollyson 2005, pp. 51–57

- ↑ Glendinning 1987, pp. 105–8 Rollyson 2005, p. 53

- ↑ Rebecca West, Introduction to Emma Goldman's My Disillusionment with Russia, Doubleday, 1923

- ↑ Rebecca West, "The men we sacrificed to Stalin," Sunday Telegraph, n.d.

- ↑ Rebecca West wrote a mordant satire in short story form of the Allies' switch titled "Madame Sara's Magic Crystal", which was published posthumously in The Only Poet (1992), edited by Antonia Till, Virago, pp. 167–78.

- ↑ Madame Sara's

- ↑ Rebecca West, "McCarthyism," U.S. News & World Report, 22 May 1953; "Miss West Files and Answer," The Herald Tribune, 22 June 1953, p. 12; "Memo from Rebecca West: More about McCarthyism," U.S. News & World Report, 3 July 1953, pp. 34–35

- ↑ Rebecca West, "Margaret Thatcher: The Politician as Woman," Vogue, September 1979

- ↑ Rollyson 2005, p. 54

- ↑ London Metropolitan Archives, Bryanston Square St Mary, Register of Baptism, p89/mry2, Item 040

- ↑ Schweizer 2002, pp. 72–76

- ↑ West, Rebecca (1994). Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. Penguin. p. 827.

- ↑ Rebecca West, "My Religion" in My Religion, edited by Arnold Bennett, Appleton, 1926. pp. 21–22]

- ↑ Rebecca West My Religion, pp. 22–23

- ↑ West, Rebecca (1933). Letter to a Grandfather. Hogarth. p. 43.

- ↑ West 1933, p. 30

- ↑ West 1994, pp. 827–8

- ↑ Rebecca West, "Can Christian faith survive this war?" interview conducted by the Daily Express, 17 January 1945

- ↑ Glendinning 1987, p. 221

- ↑ Rebecca West, Letter dated 22 June 1952, to Margaret and Evelyn Hutchinson. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

- ↑ Rebecca West, Survivors in Mexico, Yale, 2003, p. 81

- ↑ Schweizer 2002, p. 71

- ↑ Bonnie Kime Scott, Refiguring Modernism: Postmodern Feminist Readings of Woolf, West, and Barnes (Vol. 2), Indiana University Press, 1995, p. 151

- ↑ West 1994, pp. 172 ff

- ↑ West 1994, p. 827

- ↑ West 1994, p. 172

- ↑ Rebecca West, unpublished typescript, Mc Farlin Special Collections, University of Tulsa

- ↑ West 1994, p. 579

- ↑ Bonnie Kime Scott, Refiguring Modernism (Vol. 2), p. 161

- ↑ Rebecca West, Woman as Artist and Thinker, iUniverse, 2005, p. 19

- ↑ West 1933, p. 34

- ↑ Schweizer 2002, p. 141

- ↑ Peter Wolfe, Rebecca West: Artist and Thinker, Southern Illinois, 1971, p. 12

- ↑ John J. O'Connor, "Moyers and a Provocative Dame Rebecca West." The New York Times, 8 July 1981.

- ↑ Robert, D. Kaplan, Balkan Ghosts (1994), p. 3

- ↑ Opening credit reads, "From a story by Rebecca West."

- ↑ From a copy of Cousin Rosamund with an afterword by Victoria Glendinning; Macmillan, 1995.

- ↑ First published in the UK by Macmillan in 1966, and published in the US by Viking Press also in 1966.

- ↑ Rebecca West; Edited and Introduced by Bernard Schweizer (18 October 2004). "Survivors in Mexico – West, Rebecca; Schweizer, Bernard – Yale University Press". Yalepress.yale.edu. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ↑ http://www.pearhousepress.com/rebeccawest.html

External links

- Works by Rebecca West at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Rebecca West at Internet Archive

- Works by Rebecca West at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Rebecca West papers at The University of Tulsa McFarlin Library's Department of Special Collections and University Archives.

- Rebecca West Papers at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

- New York Times obituary, 16 March 1983

- Petri Liukkonen. "Rebecca West". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Archived from the original on 4 July 2013.

- International Rebecca West Society

- "Archival material relating to Rebecca West". UK National Archives.

- Biography of Rebecca West on the Yale Modernism Lab

- Marina Warner (Spring 1981). "Rebecca West, The Art of Fiction No. 65". The Paris Review.