Culture of Panama

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Panama |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Literature |

|

Music and performing arts |

| Sport |

|

Monuments |

|

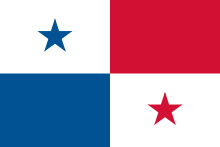

Symbols |

|

Panamanian culture is a hybrid of African, Native Panamanian, and European culture - specifically Spanish. For example, the tamborito is a Spanish dance that was blended with Native American rhythms and dance moves. Dance is a symbol of the diverse cultures that have coupled in Panama. The local folklore can be experienced through a multitude of festivals, dances and traditions that have been handed down from generation to generation.

Panamanian cuisine

Panamanian Cuisine is a mix of African, Spanish, and Native American techniques, dishes, and ingredients, reflecting its diverse population. Since Panama is a land bridge between two continents, it has a large variety of tropical fruits, vegetables and herbs that are used in native cooking.

Typical Panamanian foods are mildly flavored, without the pungency of some of Panama's Latin American and Caribbean neighbors. Common ingredients are corn, rice, wheat flour, plantains, yuca (cassava), beef, chicken, pork and seafood.(in Panama they call this example tortilla,because the arepas are from Colombia)

Literature

Panamanian historian and essayist Rodrigo Miró (1912-1996) cites Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés as the author of the first Panamanian literary work, the story of a character named Andrea de la Roca, which was published as part of the "Historia General y Natural de Las Indias" (1535). However, the first manifestations of literature written in Panama come from the 17th century with the title of "Llanto de Panamá a la muerte de don Enrique Enríquez" (Crying from Panama at the Death of Don Enrique Enríquez). Although this anthology was formed during the Colony, most of the poems in it were written by authors born in Panama.

Other Panamanian wrtiers working during Spanish Colony: Mateo Rosas de Oquendo, author of an autobiographic romance; Juan de Miramontes y Zuázola, author of "Armas Antárticas" (Antarctic Weapons); Juan de Páramo y Cepeda, author of "Alteraciones del Dariel" (Dariel Alterations); and others.

During the 19th century, the romantics: Manuel María Ayala (1785–1824) and Tomás Miró Rubini (1800–1881). Subsequently appeared José María Alemán (1830–1887), Gil Colunje (1831–1899), Tomás Martín Feuillet (1832–1899), José Dolores Urriola (1834–1883), Amelia Denis de Icaza (1836–1911), Manuel José Pérez (1837–1895), Jerónimo de la Ossa (1847–1907), Federico Escobar (1861–1912) and Rodolfo Caicedo (1868–1905).

The modernists: Darío Herrera (1870–1914), León Antonio Soto (1874–1902), Guillermo Andreve (1879–1940), Ricardo Miró (1883–1940), Gaspar Octavio Hernández (1893–1918), María Olimpia de Obaldía (1891–1985), and Demetrio Korsi (1899–1957).

The Avant-garde movement: Rogelio Sinán (1902–1994), Ricardo J. Bermúdez (1914-), Mario Augusto Rodríguez (1917-2009), José María Núñez (1894–1990), Stella Sierra, Roque Javier Laurenza, Ofelia Hooper, Tobías Díaz Blaitry (1919–2006), Moisés Castillo (1899–1974), Gil Blas Tejeira (1901–1975), Alfredo Cantón (1910-1967), José María Sánchez (1918–1973), Ramón H. Jurado (1922–1978), Joaquín Beleño (1921), Carlos Francisco Changmarín (1922), Jorge Turner (1922), and Tristán Solarte (1924)

Working during the second half of the 20th century: Tristán Solarte (1934), José de Jesús Martínez, Diana Morán (1932), Alvaro Menéndez Franco (1932), José Guillermo Ross-Zanet (1930), José Franco (1931), Elsie Alvarado de Ricord (1928–2005), Benjamín Ramón (1939), Bertalicia Peralta (1939), Ramón Oviero (1939–2008), Moravia Ochoa López (1941), Dimas Lidio Pitty (1941-2015), Roberto Fernández Iglesias (1941), Eric Arce (1942), Enrique Jaramillo Levi (1944), Jarl Ricardo Babot (1945), Ernesto Endara (1932), Enrique Chuez (1934), Justo Arroyo (1936), Rosa María Britton (1936), Victoria Jiménez Vélez (1937), Pedro Rivera (1939), Gloria Guardia (1940), Dimas Lidio Pitty (1941), Mireya Hernández (1942–2006), Raúl Leis (1947-2010), and Giovanna Benedetti (1949).

And the most recent writers: Manuel Orestes Nieto (1951), Moisés Pascual (1955), Consuelo Tomás (1957), Yolanda Hackshaw (1958), Allen Patiño (1959), Ariel Barría Alvarado (1959), Héctor Collado (1960), Gonzalo Menéndez González (1960), David Robinson Orobio (1960), Erika Harris (1963), Rogelio Guerra Ávila (1963), Carlos Fong (1967), Alexander Zanches (1968), Katia Chiari (1969), Porfirio Salazar (1970), Javier Stanziola (1971), Carlos Oriel Wynter Melo (1971), José Luis Rodríguez Pittí (1971), Eyra Harbar Gomez (1972), Melanie Taylor (1972), Salvador Medina Barahona (1973), Roberto Pérez-Franco (1976), Gloria Melania Rodríguez (1981), and Javier Alvarado (1982).

Music

Present day Panamanian music has been influenced first by the Cuevas Gunas or Kunas, Teribes, Ngöbe–Buglé and other indigenous populations, since the 16th century by the European musical traditions, specially those from the Iberian Peninsula, and then by the black population who were brought over, first as slaves from West Africa, between the 16th and 19th centuries, and then voluntarily (especially from Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, Martinique, Guadeloupe, Trinidad, Saint Lucia) to work on the Panamanian Railroad and Canal projects between the 1840s and 1914.

With this heritage, Panama has a rich and diverse music history, and important contributions to Cumbia, Saloma, Pasillo, Punto, Tamborito, Mejorana, Bolero, Jazz, Salsa, Reggae, Calypso, Rock and other musical genres.

The arts

Visual arts

Another example of Panama’s blended culture is reflected in the traditional products, such as woodcarvings, ceremonial masks and pottery, as well as in its architecture, cuisine and festivals. In earlier times, baskets were woven for utilitarian uses, but now many villages rely almost exclusively on the baskets they produce for the people.

The Kuna people are known for molas, the elaborate embroidered panels that make up the front and back of a Kuna woman's blouse. Originally the Kuna word for blouse, the term mela now refers to the several layers of cloth varying in color that are loosely stitched closely together made using a reverse appliqué process.

Performance arts

Performance arts are relatively new to the country’s art scene. The first expressions date back to the late 1990s, when local painters explored and incorporated some aspects of performance to their art shows and exhibits. Cabeza de Vélez, a Panamanian painter, was one of the first artists to introduce it. Performance arts are somewhat relegated to what is locally called ‘alternative culture’ but it is slowly gaining recognition and acceptance in the local contemporary arts circles. Today, artists such as Diego Bowie are at the forefront of the Panamanian performance arts.

Museums

The best overview of Panamanian culture is found in the Museum of the Panamanian, in Panama City. Other views can be found at the Museum of Panamanian History, the Museum of Natural Sciences, the Museum of Religious Colonial Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Museum of the Interoceanic Canal, and the national institutes of culture and music.

A number of museums located in smaller communities throughout Panama's interior strive to preserve numerous aspects of the country's pre-Columbian, colonial and post-independence heritage. Examples include the Museum of Nationality in Los Santos, located in an original colonial home and exhibiting relics from the region’s pre-Columbian inhabitants, colonial period and nascent struggle for independence from Spain. The Herrera Museum was ranked #2 of 6 things to do in Chitre by Lonely Planet travelers. The two-story museum includes permanent exhibits covering the pre-Hispanic period, the region’s first mammals, and the contact between the Spanish and the natives. The main highlight of the second floor is a carefully constructed replica of the burial site of the Indian chief (Cacique) Parita.

An additional museum will soon be opening in Chitre as part of a unique tourism/residential project currently being developed. The Cubitá Museum will allow visitors and residents the opportunity to explore the variety of cultural influences that have shaped the history, art and folklore of the Azuero Peninsula, and to appreciate the unique and painstakingly crafted work of local artisans.

A scholarly analysis of Panamanian Museums, their history, exhibitions and social, political and economic contexts is available in the 2011 book "Panamanian Museums and Historical Memory".[1]

See also

- Public holidays in Panama

- Pollera, national dress

- Señorita Panamá

References

- ↑ Sánchez Laws, Ana Luisa (2011). Panamanian Museums and Historical Memory. Oxford: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-0-85745-240-5.

.svg.png)