Cultural references to Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci (April 15, 1452 – May 2, 1519) was an Italian Renaissance painter and polymath who achieved legendary fame and iconic status within his own lifetime. His renown primarily rests upon his brilliant achievements as a painter, the Mona Lisa and the Last Supper, being two of the most famous artworks ever created, but also upon his diverse skills as a scientist and inventor. He became so highly valued during his lifetime that the King of France bore him home like a trophy of war, supported him in his old age and, according to legend, cradled his head as he died.

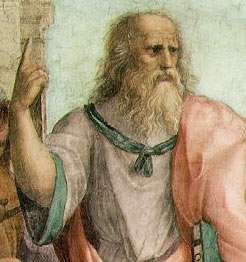

Leonardo's portrait was used, within his own lifetime, as the iconic image of Plato in Raphael's School of Athens. His biography was written in superlative terms by Vasari. He has been repeatedly acclaimed the greatest genius to have lived. His painting of the Mona Lisa has been the most imitated artwork of all time and his drawing the Vitruvian Man iconically represents the fusion of Art and Science.

Leonardo's biography has appeared in many forms, both scholarly and fictionalized. Every known aspect of his life has been scrutinized and analyzed. His paintings, drawings and notebooks have been studied, reproduced and analyzed for five centuries. The interest in and appreciation of the character of Leonardo and his talents has never waned.

Leonardo has appeared in many fictional works, such as novels, television shows and movies, the first such fiction dating from the 16th century. Various characters have been named after him.

Artworks after originals by Leonardo

Copies

Leonardo's pupils and followers copied or closely imitated many of his pictures. Several of his important works exist only as copies by his admirers. These include:

- His cartoon of The Virgin and Child with St Anne and St John the Baptist copied as an oil painting by Luini

- The Battle of Anghiari was copied several times by unknown Florentine artists as well by Peter Paul Rubens.

- Leda and the Swan exists only as copies in the Louvre and Villa Borhgese.

Other much much-copied works include:

- Mona Lisa for which Angela della Chiesa cites 14 examples of which 6 are bare-breasted. These include paintings by Bernardino Luini, Salaì and Joos van Cleve.

- John the Baptist for which there exist at least five versions by other hands including Salai.

Parodies

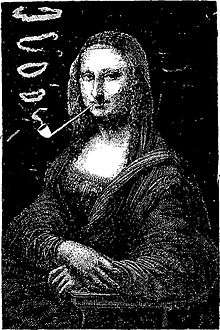

No painting has been more imitated and satirised than the Mona Lisa. Beginning possibly with a naked portrait of Diane de Poitiers by Clouet, the pose and expression have been freely adapted to many female portraits. The avant-garde art world has made note of the undeniable fact of the Mona Lisa's popularity. Because of the painting's overwhelming stature, Dadaists and Surrealists often produce modifications and caricatures. Already in 1883, Le rire, an image of a Mona Lisa smoking a pipe, by Sapeck (Eugène Bataille), was shown at the "Incoherents" show in Paris. In 1919, Marcel Duchamp, one of the most influential modern artists, created L.H.O.O.Q., a Mona Lisa parody made by adorning a cheap reproduction with a moustache and a goatee, as well as adding the rude inscription, when read out loud in French sounds like "Elle a chaud au cul" literally translated: "she has a hot ass". This is a manner of implying the woman in the painting is in a state of sexual excitement and availability. This was intended as a Freudian joke,[1] referring to Leonardo's alleged homosexuality. According to Rhonda R. Shearer, the apparent reproduction is in fact a copy partly modelled on Duchamp's own face.[2]

Salvador Dalí, famous for his surrealist work, painted Self portrait as Mona Lisa in 1954.[3] In 1963 following the painting's visit to the United States, Andy Warhol created serigraph prints of multiple Mona Lisas called Thirty are Better than One, like his works of Marilyn Monroe (Twenty-five Coloured Marilyns, 1962), Elvis Presley (1964) and Campbell's soup (1961–1962).[4]

Replicas of lost works

"Il Gran Cavallo". This monumental bronze horse, 7 metres (24 feet) high, is a conjectural re-creation of a clay horse that was created in Milan by Leonardo da Vinci for the Ludovico Sforza and was intended to be cast in bronze. Leonardo never finished the project because of war with France, and the clay horse was ruined. This representation was based on a number of Leonardo's preparatory drawings. It was created in 1999 in New York and given to the city of Milan.

Presentation of existing works

The Last Supper is to be the subject of an animation by British film-maker Peter Greenaway, who plans to project interpretative images onto its surface to enliven the scene in which the apostles all question Jesus' statement that one of them will betray him.[5]

Representations of Leonardo in art

The Death of Leonardo

The story of Leonardo dying in the arms of the French king Francis I, although apocryphal,[6] appealed to the self-image of later French kings and to French history painters of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Apparently on commission from Louis XVI,[7] Ménageot painted The Death of Leonardo da Vinci in the arms of Francis I in 1781, setting it in a background of classical statuary. This painting, which was the triumph of the Salon of 1781, included a portrayal of the Borghese Gladiator (Ménageot probably having seen it at the Villa Borghese during his stay at the French Academy in Rome from 1769 to 1774), although this was an anachronism since Leonardo died in 1519, about ninety years before the statue was discovered.

In 1818 the French painter Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres depicted the scene of Leonardo's death which is shown taking place in the home Clos Lucé provided for him at Amboise by King Francis I. The King is shown supporting Leonardo's head as he dies, as described by Vasari, watched by the Dauphin who is comforted by a cardinal. A distraught young man may represent Leonardo's pupil Melzi.

The treatment of this subject by Ingres is indicative of Leonardo's iconic status and also specifically that he was of particular significance to the school of French Classicism. A number of his paintings had passed into the Royal collection and certain elements of them were much imitated. Leonardo's manner of soft shading known as sfumato was particularly adapted by Ingres, Jacques-Louis David and their followers. An influential painting was Leda and the swan, now regarded as by a pupil of Leonardo but then generally accepted as the master's work.

Statues

- A monument to Leonardo was erected in 1872 in Piazza del Scala, Milan. It comprises five marble statues by Pietro Magni, of Leonardo and his pupils Cesare da Sesto, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, Marco d'Oggiono and “Andrea Salaino”, and four reliefs depicting scenes in Leonardo’s life.

- A statue of Leonardo by the Bulgarian sculptor Assen Peikov stands outside Leonardo da Vinci–Fiumicino Airport (Rome).[8]

Leonardo Monument, Milan

Leonardo Monument, Milan The statue of Leonardo outside the Uffizi, Florence

The statue of Leonardo outside the Uffizi, Florence- Statue of Leonardo in the pose of a river god in Amboise

References in other media

Novels and short stories

- The Romance of Leonardo da Vinci (1901) by Dmitry Merezhkovsky.

- The Second Mrs. Giaconda (1975) by E. L. Konigsburg is a children's novel about why Leonardo painted the Mona Lisa.

- Leonardo Da Vinci: Detective a short story by Theodore Mathieson, portrays him using his genius to solve a murder during his time in France.

- Pasquale's Angel by Paul J. McAuley, set in an alternate universe Florence, portrays Leonardo as "the Great Engineer", creating a premature industrial revolution (see clockpunk).

- The novel The Memory Cathedral by Jack Dann is a fictional account of a "lost year" in the life of Leonardo. Dann has his genius protagonist actually create his flying machine.

- The novel Pilgrim by Timothy Findley describes the encounters of an immortal named Pilgrim with Leonardo da Vinci among others, as told to Carl Jung.

- Terry Pratchett's character Leonard of Quirm is a pastiche of Leonardo.

- Three novels by Martin Woodhouse and Robert Ross feature the adventures of Leonardo da Vinci in the guise of a James Bond-type spy of the Italian Renaissance: The Medici Guns (1974); The Medici Emerald and The Medici Hawks.

- The Secret Supper (2006) by Javier Sierra explores the symbology of Leonardo's Last Supper, and its threat to the Catholic Church, as he is painting the fresco in 15th century Milan.

- Black Madonna (1996) by Carl Sargent and Marc Gascoigne, is set in the Shadowrun game universe and portrays Leonardo as still living in the 21st century, blackmailing corporations to finance his inventions.

- The Medici Seal, a children's novel by Theresa Breslin (2006).

- In the Children of the Red King series, a Donatella Di Vinci married a Bertram Babbington-Bloor. Donatella was the daughter of an Italian magician. No connection between Leonardo and Donatella has been stated since.

- In Robert Heinlen's The Door Into Summer, Dr. Twitchell recounts a tale of a student whom he displaced in time by 500 years. While there was no way of knowing whether the student went to the past or the future, Dr. Twitchell hints that he believes it was the past due to the student's name—Leonard Vincent.

- In the novel Saturn's Apprentice by M.A. Lang, an alchemical experiment gone wrong causes Leonardo to be lost in the present day, while back in Renaissance Florence his friend Tomasso Masini desperately tries to save him.

- Leonardo da Vinci is a significant character in the novels; Assassin's Creed: Renaissance and Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood (novel), books based on the video game series Assassin's Creed. Leonardo is portrayed as a close friend of the protagonist, Ezio Auditore da Firenze, a Florentine nobleman's son who joined the Assassin Brotherhood after the murder of his father and brothers by the ruling families of Italy, each part of the once thought disbanded Knight's Templar. Leonardo helps the assassin decipher encrypted codex pages left behind by legendary master assassin, Altair (the protagonist of the original Assassin's Creed game). Leonardo's flying machine is successfully built and helps Ezio travel across Venice in order to assassinate one of his targets. Leonardo makes a brief appearance in Assassin's Creed: Revelations (novel). Ezio and his close friend and fellow Assassin, Niccolò Machiavelli visit him during the week that he died, present at his side while he passes away. Machiavelli recalls a rumour that King Francis cradled his head in his arms as he died, to which Ezio remarked: "'Some people – even Kings – will do anything for publicity'".

The Da Vinci Code

This work of fiction has been the centre of controversy over the accuracy of its depictions of Christianity and of da Vinci.

A bestselling 2003 novel by Dan Brown, adapted and released as a major motion picture in 2006, The Da Vinci Code revolves around a conspiracy based on elements of Leonardo's Last Supper and other works. A preface to the novel claims that depictions of artworks, secret societies and rites described within the novel are factual. For this reason much of the content of the novel has been widely accepted by readers as authoritative. Because the theme involves a conspiracy within the Church over the life of Jesus and the suggestion that the Church has hidden the facts of his marriage, there has been a strong reaction against the novel and much material published examining and refuting its claims.

Within the novel it is claimed that from 1510–1519, Leonardo was the Grand Master of a secret society, the Priory of Sion. In reality this society existed only as a 20th-century hoax, but author Dan Brown used as a source the 1982 pseudohistory book The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail. The writers of this book had based their research on forged medieval documents that had been created as part of the Priory of Sion fraud. The mix of fact and fiction in the documents made it difficult to discount immediately as a forgery. For example, it was claimed that the Grand Master prior to Leonardo was Botticelli, who had indeed had an association with Leonardo, as they were both students at the Florence workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio.

The Priory of Sion story and the veracity of The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail was eventually debunked, and many of those involved publicly recanted, although Dan Brown continued to assert that the facts as presented were true.

In portraying the Priory of Sion as "fact" The Da Vinci Code expanded on the claims in The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail:

- That there were additional secrets hidden in Leonardo's paintings, such as an "M" letter in the painting of The Last Supper, indicating the presence of Mary Magdalene and that the figure to the left of Jesus traditionally said to represent John the Evangelist actually represents Mary Magdalene.

- That the Mona Lisa was actually a self-portrait.

- That among the differences in the two versions of the painting of the Virgin of the Rocks which hang in the Louvre and London's National Gallery, is the fact that in the Louvre painting the baby to the left of the picture depicts Jesus, and to the right John the Baptist, rather than the accepted view, which is the other way round.

- That Leonardo invented a cryptex for carrying secret messages.

The book also used a variation of Leonardo's backwards handwriting to hide a secret message on the American bookjacket.

Among the many criticisms of Brown's writing is that he uses the name da Vinci (meaning "from Vinci") in the manner that surnames are commonly used nowadays. Leonardo would never have been referred to simply as da Vinci in his lifetime. Such designations were appended to common baptismal names in order to identify individuals.

Film

Films which are about the life of Leonardo or in which he appears as a character:

- Leonardo Da Vinci (1919), silent film[9]

- The Life of Leonardo da Vinci (1971) starring Philippe Leroy as Leonardo da Vinci

- Nothing Left to Do But Cry (1984) starring Roberto Benigni and Massimo Troisi

- Quest of the Delta Knights (1993) depicting a fictional version of the young Leonardo

- Leonardo Da Vinci (1996) – Animated movie[10]

- Ever After (1998) starring Drew Barrymore and Patrick Godfrey as Leonardo da Vinci

- Christie Malry's Own Double-Entry (2000) starring Mattia Sbragia as Leonardo da Vinci[11]

- Leonardo (2003), TV movie starring Mark Rylance as Leonardo da Vinci[12]

- "Mr. Peabody & Sherman" (2014), da Vinci and Peabody work together to build a machine to recharge the wabac. However, Peabody first helps da Vinci make Mona Lisa smile. At the end of the film, da Vinci and Mona Lisa are doing graffiti.

Films which refer to Leonardo's works or inventions:

- Hudson Hawk (1991) starring Bruce Willis and Danny Aiello revolves around Leonardo da Vinci's inventions

- The Da Vinci Code (2006) starring Tom Hanks

- The Da Vinci Treasure (2006) depicts Da Vinci's paintings as clues that lead to enlightenment

- The Three Musketeers (2011) depicts the musketeers stealing plans by Da Vinci for an airship from 'Leonardo's vault' in Venice

- "Mr. Peabody & Sherman" (2014 film) Sherman and Penny fly through Florence with da Vinci's flying machine until Peabody spots them.

Theatre

- Peter Barnes's 1969 play Leonardo's Last Supper centres on Leonardo being "resurrected" in a filthy charnel house after being prematurely declared dead.

- David Davalos's 2002 play Daedalus tells a fantasized story of Leonardo's time as a military engineer in the service of Cesare Borgia, in the company of Lucrezia Borgia and Niccolò Machiavelli.

Music

- Author Charles Anthony Silvestri and composer Eric Whitacre collaborated to create an "opera bréve" based on text from da Vinci's journals and original text by Silvestri. This piece, Leonardo Dreams of His Flying Machine, was modeled after da Vinci's conceptual flying machine. This piece was written on commission by the American Choral Directors Association as the second piece in Whitacre's series of "Element Works," the first being Cloudburst, written in 1992.

- Dream Theater vocalist James LaBrie performed as Leonardo in the progressive metal album 'Leonardo: The Absolute Man', an album which itself explored his life and works through the milieu of music.

- In the Red Hot Chili Peppers video for Californication, a cartoon John Frusciante can be seen riding Leonardo's helicopter.

- Mona Lisa is used as a stage name by Kimberley Leadbetter, an American pop and R&B singer-songwriter.

- The Ballad of Mona Lisa is a song by Panic! at the Disco, an American rock band, published in February 2011.

Television fiction

- 1966: In the SF sitcom My Favorite Martian episode "Martin Meets His Match", Martin uses his time machine to bring Da Vinci to the present day to help him repair his spaceship. Instead, da Vinci decides to steal back his painting the Mona Lisa and take it back with him.

- 1967: In the Bewitched episode "Samantha's Da Vinci Dilemma", Aunt Clara tries to conjure up a house painter, but she goofs and summons Leonardo da Vinci from the past instead.

- 1969: In the Star Trek episode "Requiem for Methuselah", Leonardo da Vinci is revealed to be one of many aliases to "Flint", an immortal man born in the year 3834 BC. Leonardo's abilities and knowledge are thus attributed to centuries of scientific and artistic study. Leonardo appears again in the Star Trek universe, in the series Star Trek: Voyager, where he and his workshop are created as a holographic simulation. Actor James Daly played Flint/Leonardo in Star Trek, while John Rhys-Davies portrayed Leonardo in Star Trek: Voyager. Also, in the S.C.E. (Starfleet Corps of Engineers) novellas, the main starship of the series is called the U.S.S. da Vinci (NCC-81623), a Sabre-class vessel, named for the artist.

- 1969: In the Ironside Season 2 episode "The Prophecy," a fictional Leonardo painting called "The Seraglio" is stolen from a museum. A psychic friend of Ironside's tells Mark Sanger he will catch "a lovely black girl all in silver and emeralds with golden rings around her ankles," and it is Mark who saves the painting—which features a bejeweled black woman dancing in a seraglio—from rolling into the sea toward the end of the episode.

- 1970: In the British comedy series Monty Python's Flying Circus in the "Art Gallery Strike" sketch in the episode "Spam", the Mona Lisa was used in two animated links by Terry Gilliam, the first as one of many paintings going on strike (she dons a cap and declares in a low-pitched voice, "I'm off") and as a temptress who reveals large breasts under her garment; here she tells the viewer (in a seductive, smoky American accent), "Come over here to my window, big boy."

- 1979: The Doctor Who story City of Death features a theft of the Mona Lisa. The Doctor goes back in time to visit Leonardo's workshop and claims to be an old acquaintance of the artist. Leonardo also appears as a character in several Doctor Who novels.

- 1984- : In the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles cartoon series, comics, films, and other media, the leader of the turtles is named Leonardo after Da Vinci.[13]

- 1989: In The Super Mario Bros. Super Show! live-action segment "The Painting", the Mario Bros. find a painting which happens to be Leonardo da Vinci's painting "The Last Supper". They call up Howard Stevens (played by the show's producer Andy Heyward), and he explains that it's the "second Last Supper" by Leonardo da Vinci "Rooney". However, upon further examination, they discover that the painting is actually worthless because it was painted by an impostor, Leonard da Vinci "Mahoney". Howard was able to identify it as Mahoney's painting because one of the people in the painting is Mahoney's uncle, Roy Orbisoni Mahoney. The information dealing with da Vinci in this episode is incorrect.

- 1989-1990: The anime Time Quest features Professor Leonardo as inventor of the kettle-shaped time machine, who is revealed to be Leonardo da Vinci in the final episodes.

- 1995: The cartoon The Tick features Leonardo in "Leonardo DaVinci and his Fightin' Genius Time Commandos!" (Season 2, Episode 17) in which a number of famous inventors are brought to the present by an inventor seeking to take credit for their work. (Other inventors include Ben Franklin, George Washington Carver, and the neolithic inventor of the wheel, named Wheel.) Leonardo is portrayed as being able to create fantastic flying devices out of rudimentary objects.

- 1998: An episode of Histeria! focusing on the Renaissance featured a cartoon caricature of Leonardo as a host. Over the course of the episode, he is criticized by World's Oldest Woman for wearing a dress, and also parodies the 1960s Batman series as Renaissance Man, with Loud Kiddington as his sidekick.

- 1999: In the animated television series Dilbert (TV series) episode "Art" has Leonardo as the secret ruler of the art world. He reveals that he discovered immortality centuries ago through the invention of the fountain of youth.

- 1999: In Blackadder: Back & Forth, Baldrick builds a time machine to Leonardo's exact design specifications and it actually works. Earlier in the Blackadder series the episode Money featured a painter by the name of “Leonardo Acropolis”, ostensibly based on Leonardo.

- 2001-2006: The television show Alias features a character Milo Giacomo Rambaldi, a fictional character clearly based on Leonardo.

- 2006: Featured on the History Channel's Man, Moment, Machine.

- 2006: The Boston Legal episode "The Nutcrackers" portrayed the main character, Alan Shore, as the Mona Lisa, a play on his stoic demeanor in the show.[14]

- 2010: The Futurama episode "The Duh-Vinci Code" reveals Leonardo to be an alien from Planet Vinci, which is inhabited by brilliant intellectuals of human appearance. However, he is considered to be the least intelligent of the planet's inhabitants and is bullied by everyone else for it. He came to Earth as a means of escape, but eventually returned to Vinci after being disillusioned by how much more unintelligent the people of Earth were compared to him. He builds a new machine designed to kill his tormentors, but it is sabotaged by Philip J. Fry, and Leonardo is crushed to death when he pulls a lever on the machine that drops a giant cog on him.

- 2011: The Family Guy episode "The Big Bang Theory" follows Stewie and Brian on a quest to stop Bertram from killing Leonardo, which would permanently erase Stewie from the universe.

- 2011-2012: The BBC series Leonardo centers around Da Vinci when he was a teenager (played by Jonathan Bailey).

- 2013: Da Vinci's Demons is an historical fantasy series about Leonardo da Vinci at the age of 25. Da Vinci is involved in political intrigue amongst the Italian city-states, the Vatican, and the mystery cult known as the Sons of Mithras.

- 2013: In the Sky Arts feature-length documentary Inside the Mind of Leonardo, Da Vinci is played by Peter Capaldi.

Advertising

- Benetton's 1988 "United Superstars of Benetton" print and billboard campaign, paired with Julius Caesar[15]

Comics and graphic novels

- The DC Comics Elseworlds story "Black Masterpiece", in Batman Annual No. 18, shows Leonardo's apprentice becoming a Renaissance Batman, using the Master's devices in his war on Florentine crime.

- DC Comics's Vertigo division published a ten-issue miniseries "strongly laced with sex, violence, and magic"[13] about Leonardo, entitled Chiaroscuro: The Private Lives of Leonardo da Vinci.[13]

- In the mainstream DC Universe, according to Secret Origins No. 27, Leonardo is an ancestor of the famed Freemason Cagliostro, as well as Zatara and Zatanna who are both magicians (in both the Magic (illusion) and Magic (paranormal) senses) and superheroes. Also, in Final Night No. 2, it was revealed that Vandal Savage had blackmailed Leonardo into painting the Mona Lisa.

- The Dargaud cartoon character Léonard by Turk and De Groot.

- The Daily Mirror comic strip character Garth saved Leonardo from the Black Death in the 1972 strip Orb of the Trimandias, written by Jim Edgar and illustrated by Frank Bellamy.

- In 1979, the French weekly Journal de Mickey published a Mickey Mouse adventure based in Renaissance Florence. Goofy is Leonardo, and Mickey gets him to paint the portrait of Mona Lisa, who is represented by Clarabelle Cow.

- Leonardo appeared as a character in the now defunct Marvel Comics imprint Epic Comics mini series The Light and Darkness War.

- Leonardo da Vinci appears in the current Marvel S.H.I.E.L.D. series (which is now a series of mini series) by Jonathan Hickman. Leonardo is depicted as a leader of a sacred order called the Brotherhood of the Shield, and has been shown to time travel to the story's "present", set in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Computer and video games

- In Mario's Time Machine, the MS-DOS and SNES releases of the game feature Leonardo as a non-player character. His notes are stolen by Bowser after the latter travels back in time, and Mario travels back in time himself to Florence to return the notes. In the area, Mario meets several of Leonardo's contemporaries, including Michelangelo and an apprentice of Andrea del Verrocchio, who talk about Leonardo's past, innovations, and status as a "Renaissance man." Some of Leonardo's work is also seen, including his concept of a helicopter (referred to in-game as a "drawing of air screw"), his Vitruvian Man (referred to in-game as a "drawing of Ideal Man"), and the Mona Lisa, which he can only complete once Mario returns his notes to him.

- In The Journeyman Project 2: Buried in Time a temporal saboteur has tampered with several historical items in the past to pass on technological information to an alien race. One of them is the Codex Atlanticus. The player is to explore da Vinci's studio while he was working for Ludovico Sforza.

- In Rise of Legends (2006), the Vinci faction uses steampunk technology inspired by Leonardo.

- In Soulcalibur Legends there is a character that bears a striking resemblance to Leonardo, and even has the same name.

- In Elite Beat Agents, one mission has the agents go back in time to help Leonardo paint the Mona Lisa. He is only ever referred to as "Leo" or "Leonard".

- In Civilization, Leonardo's Workshop is one of the most useful "World Wonders"; Leonardo also appears as a "Great Person".

- Leonardo is an important supporting character in Assassin's Creed series. In Assassin's Creed II, a young Leonardo befriends the protagonist, Ezio Auditore da Firenze, in 1476 when introduced by Ezio's mother Maria, a patron of Leonardo's. He later helps Ezio by deciphering pages of an ancient Assassin Codex written by legendary Assassin Mentor Altaïr Ibn-La'Ahad and using his mechanical know-how to build various devices, inventions and weapons. An older Leonardo appears in Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood, having been forced to make war machines for Cesare Borgia and Rodrigo Borgia and asking Ezio to help him by destroying them. In the DLC The Da Vinci Disappearance for Brotherhood, Leonardo is kidnapped by Hermeticists, members of the Cult of Hermes, and Ezio must rescue him. The DLC also includes Leonardo's pupil and suspected lover, Salaì.

- In Super Monday Night Combat, a clone of Leonardo da Vinci under the name of "Leo" is playable.

- In LittleBigPlanet 2, a tutorial and supporting character is also named Da Vinvi with some few difference: he wore 3-d glasses, his head is made of craft, and his first name is "Larry".

Online

- 2014: In the Epic Rap Battles of History episode "Artists vs. TMNT", da Vinci, portrayed by Link Neal of Rhett and Link, appears alongside portrayals of Donatello, Michelangelo and Raphael, engaged in a battle rap with the eponymous Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

Gallery

.png) Engraving from "The Swedish Family Journal", 1864–87, artist Evald Hansen.

Engraving from "The Swedish Family Journal", 1864–87, artist Evald Hansen. An engraved representation of da Vinci from Wallace Wood's The Hundred Greatest Men (1885), based on an 1817 engraving by Raffaello Sanzio Morghen.[16]

An engraved representation of da Vinci from Wallace Wood's The Hundred Greatest Men (1885), based on an 1817 engraving by Raffaello Sanzio Morghen.[16] Leonardo's drawing of the Vitruvian Man is used in many contexts, including T-shirts.

Leonardo's drawing of the Vitruvian Man is used in many contexts, including T-shirts. The Last Supper carved in salt in the Wieliczka Salt Mine

The Last Supper carved in salt in the Wieliczka Salt Mine

References

- ↑ Jones, Jonathan (26 May 2001). "L.H.O.O.Q., Marcel Duchamp (1919)". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- ↑ Marting, Marco De (2003). "Mona Lisa: Who is Hidden Behind the Woman with the Mustache?". Art Science Research Laboratory. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ↑ Dalí, Salvador. "Self Portrait as Mona Lisa". Mona Lisa Images for a Modern World by Robert A. Baron (from the catalog of an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973, p. 195). Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ↑ Sassoon, Donald (2003). Becoming Mona Lisa. Harvest Books via Amazon Search Inside. p. 251. ISBN 0-15-602711-9.

- ↑ Robert Booth (2008-02-15). "Greenaway prepares to create Da Vinci coda". The Guardian. Retrieved 2013-07-24.

- ↑ King Francis cannot have been present because the day after Leonardo's death, a royal edict was issued by the King at Saint-Germain-en-Laye, a two-day journey distant from Clos Luce.

- ↑ According to François-Charles Joullain fils, Réflexions sur la peinture et la gravure 1786:2.

- ↑ Shkodrova, Albena. "Innocent as a Barbarian, Nostalgic for a Lost World". Balkan Travellers. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ Leonardo Da Vinci at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Leonardo Da Vinci at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Christie Malry's Own Double-Entry at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Leonardo at the Internet Movie Database

- 1 2 3 Fairbrother, Trevor (1997). "The Ongoing Saga of Leonardo's Legend". In Kotz, Suzanne. The Ongoing Saga of Leonardo's Legend (ill. ed.). Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, in assoc. w. University of Washington Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-295-97688-4. OCLC 37465464. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ↑ "Script for Boston Legal episode "The Nutcracker"" (PDF). p. 11. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ↑ "Benetton Group: Evolution of Communication Strategy" scribd.com Accessed February 21, 2010

- ↑ "Leonardo da Vinci". lacma.org. Retrieved November 8, 2015.