Crucifix (Cimabue, Santa Croce)

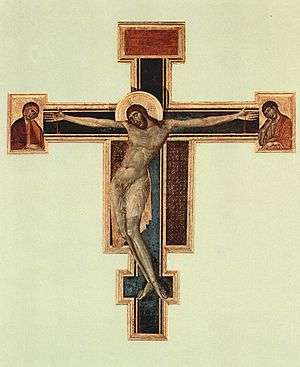

Crucifix (c. 1265) is a wooden crucifix, painted in distemper, attributed to the Florentine painter and mosaicist Cimabue. It is one of two large crucifixes attributed to him.[1] The work was commissioned by the Franciscan friars of Santa Croce and is built from a complex arrangement of five main and eight ancillary timber boards. It is one the first Italian artworks to break from the late medieval Byzantine style and is renowned for its technical innovations and humanistic iconography.

The gilding and monumentality of the cross links it to the Byzantine tradition. Christ's static pose is reflective of this style, while the work overall incorporates newer, more naturalistic aspects. The work presents a lifelike and physically imposing depiction of the passion at Calvary. Christ is shown nearly naked: his eyes are closed, his face lifeless and defeated. His body slumps in a position contorted by prolonged agony and pain. A graphic portrayal of human suffering, the painting is of seminal importance in art history and has influenced painters from Michelangelo, Caravaggio and Velasquez to Francis Bacon.[2]

The work was been in the Basilica di Santa Croce, Florence, since the late thirteenth century, and at the Museo dell'Opera Santa Croce since restoration following flooding of the Arno in 1966.[3][4] It remains in poor condition despite conservation efforts.

Commission

Both of Cimabue's surviving crucifixes were commissioned by the Franciscan order. Founded by Saint Francis of Assisi, their reformist, religious and social views had a profound effect on the visual arts in the century after his death. The son of a wealthy cloth merchant, Francis abandoned his inheritance to take up preaching in his mid-twenties. He venerated poverty and developed a deep appreciation for the beauty of nature. Byzantine depictions tended to show Christ as invincible, even in death. Imagery based on Franciscan ideals in the 13th century generally reinforce his veneration of simplicity and naturalism, infusing the paintings with the new values of humanism.[5][6]

The church at Santa Croce was the third that the Franciscans constructed at the site. The first was begun in 1295, and is where Cimabue's Crucifix probably hung, given its large size, above the rood screen.[7] It was later positioned at the north transept, in the sacristy and by the entrance on the southern flank.[8]

Description

Cimabue achieves a masterful handling of colour; medieval churches tended to be extremely colourful, with frescoed walls, painted capitals, and gold leaf paintings.[9] Pale tonalities dominate, with the main contrast found in the dark areas of Christ's hair and beard, which are utilised to make the features of his face stand out more, and position his head as the focal point.[10]

Crucifixion

Compared to earlier works of this type, Christ's body is more physically corporeal and his anatomy more closely rendered. His hands and feet seem to extend beyond the pictorial space, which is delineated by the flat, coloured borders of the cross,[5] in turn made up of at least six boards. Both Christ's body and his semi-circular nimbus are placed at angles which rise outwards and above the level of the cross.[11]

His body arches, forcing his torso to raise against the cross. Blood pours from the wounds in his hands as his head falls to the side from fatigue and the physical reality of approaching death.[12] His is naked except for a sheer and transparent loincloth that only just covers his thighs and buttocks. The choice of a white, veil-like loincloth, dramatically more modest than the red garment in the Arezzo work, may be influenced by earlier crucifixions by Giunta Pisano.[13] His nakedness highlights his vulnerability and suffering. It seems influenced by a thirteenth-century Franciscan Meditation on Christ that emphasised pathos and human interest in the suffering of the Passion; "Turn your eyes away from His divinity for a little while and consider Him purely as a man".[14]

His eyes are open and his skin is unblemished. The cross is painted with deep blue paint, perhaps evoking an eternal or timeless sky.[15] This evocation, not present in the main crucified figure, was known as the Christus triumphans ("Triumphant Christ"), and for contemporary, especially Franciscan, taste, lacked verisimilitude, as it bore little relation to the actual suffering likely endured during a crucifixion, and overly distanced the divine from the human aspect of Christ.[7][16] From about 1240, painters favoured the Christus patiens ("Suffering Christ") style: a saviour who shared the burden and pain of humanity. The Santa Croce Crucifix is one of the earliest and best known examples of the type.[17]

The work surpasses Cimabue's c. 1268 Arezzo crucifix in several ways. It is more human and less reliant on idealised facial types,[14] and the anatomy is more convincing. Christ's face is longer and narrower, and his nose less idealised. These features, according to art historian Robert Gibbs, give him "a coarser but more personal expression".[13] A similar approach is taken with the cloth in the background of the cross itself, which although highly ornamented, lacks the lavish ornamentation of the equivalent cloth in the Arezzo cross.[10]

His head hangs in exhaustion, his hands bleed from the puncture wounds suffered during his nailing to the cross.[12] His arms are placed higher above his head and strain to carry the weight of his body, which visibly slumps.[14] His body takes on a dramatic, almost feminine curve, the result of the contortions forced upon a body nailed to a vertical support.[18]

The painting contains elements typical of Cimabue's representations of Christ, including the illusionism of the drapery folds, the large halo, long flowing hair, dark angular faces and dramatic expressions.[19] But in other respects it conforms to the then strict iconography of the 13th century. Typical of depictions of the crucified Christ of this era, with his outstretched arms he is as wide as he is long; conforming to prevalent ideals of proportions.[20]

Saints

Representations of the Virgin and John the Evangelist flank Christ in small rectangular panels at either end of his outstretched arms. Both are dark skinned, bear agonised and sorrowful expressions as they rest their heads on their right hands, and face inwards towards Christ. In keeping with the Franciscan idea, the gilding surrounding the mourning saints is kept to a minimum. The size and positions of the figures is reduced compared to usual Byzantine iconography[5] to maintain sole focus on the passion of Christ.[21]

Their cloaks are simpler and lack the lavish gilding of the Arezzo crucifixion.[10] The Virgin wears a red dress. Her robe was originally blue but has darkened.[22]

Carpentry

The crucifix measures 448 cm x 390 cm and consists of five basic physical components; a vertical board reaching from the base to the cymatium onto which Christ is nailed, two horizontal cross-arms, and two vertical pieces acting as aprons adjacent to the central board. There are another eight minor pieces; mostly terminals, bases or framing devices.[23] The structure is reinforced by two full length vertical battens. The horizontal cross-arms extend the full width of his outstretched body, and are slotted into ridges in the vertical supports. The timber would have been cut and arranged by carpenters before Cimabue applied his design and paintwork.[23]

Its dimensions are highly symmetrical and proportionate, probably influenced by the geometric ideals, ratios and rules of design of the ancient Greeks. The balance of measurements, especially between the width and height of the cross, seem derived from the sides and diagonals of squares, and dynamic rectangles.[24] Cimabue was not rigid in his placement however, and to accommodate the sway of Christ's body, altered the positioning of some of the boards on the lower half.[25]

Attribution

Due to lack of surviving documentation, it is difficult to attribute unsigned works from the period with any degree of certainty. The Crucifix's origin has often been contested, but is generally thought to be by Cimabue based on stylistic traits and mentions by both Vasari and Nicolò Albertini.[13][26] It is relatively primitive compared his 1290s works, and is thus believed to date from his early period.[27] According to Vasari, the crucifix's success lead to the commissions at Pisa, Tuscany that established his reputation.[26]

Rejecting these views, Joseph Archer Crowe and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle in 1903 concluded that the Santa Croce crucifix "in technical examination...makes some approach to the Florentine master, but it is rather of its time than by the master himself."[28]

1966 damage and restoration

The crucifix was installed in the church of Santa Croce at the end of the thirteenth century and remained there until 1966, when the banks of the Arno river burst and flooded Florence. Thousands of art works were damaged or destroyed; the Crucifix lost 60% of its paint. It had suffered earlier flood damage in 1333 and 1557. In 1966 it was on display in the lower Museo dell' Opera, which is at a lower elevation and closer to the waterline than the Santa Croce church, where it was located during earlier floods. The water level reached the height of Christ's halo and took large tracts of paint when it retreated. The water deposited oil, mud and naphtha on the wood frame,[29] which further swelled from soakage, forcing the panel to expand and bend, cracking the paint-work.[30]

A team of restorers led by conservators Umberto Baldini and Ornella Casazza at the "Laboratario del Restauro" in Florence,[29][31] spent ten years reapplying paint. They worked in an almost pointillist manner, with the aid of computer modelling. The tiny specks of pigment floating around it were recovered with pliers by staff wading in the water after the torrents had subsided.[29] The wooden frame had significantly weakened, and it was necessary to separate it from both the gesso and canvas to prevent buckling as the reapplied paint dried.[29] The restorers succeeded in returning the work close to its original appearance, and it was put back on public display in 1976.[12]

The restoration was covered by the international press; since then the work has been loaned to galleries outside Italy, the first time it had left Florence since its inception. According to the critic Waldemar Januszczak it was brought "around the globe in a curious, post-restoration state—part original artwork, part masterpiece of modern science ... a thirteenth century—twentieth-century hybrid."[32]

References

Notes

- ↑ The other is the Arezzo crucifix. See Chiellini, 8

- ↑ Bacon said: "You know the great Cimabue Crucifixion? I always think of that as a worm crawling down the cross." Sylvester, 14

- ↑ Emmerson, 256

- ↑ It was in the Uffizi from 1948 to 1959 and is sometimes referred to as the Uffizi Crucifix. See Cecchi, 65

- 1 2 3 Kleinhenz, 224

- ↑ Paolettii, 49

- 1 2 Thompson, 61

- ↑ Jacks, 492

- ↑ Chiellini, 8

- 1 2 3 Chiellini, 15

- ↑ Farthing, 43

- 1 2 3 Larson, Kay. "Survival of the Greatest". New York Magazine, 27 September 1982

- 1 2 3 Gibbs, Robert. "Cimabue". Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 October 2016

- 1 2 3 Paolettii, 52

- ↑ Isaac, 2-3

- ↑ Paolettii, 50

- ↑ Osborne, 245

- ↑ Paolettii, 51

- ↑ Bologna, 333

- ↑ Chiellini, 11

- ↑ Hourihane, 229

- ↑ Messina, 45

- 1 2 Brink, 646

- ↑ Brink, 647

- ↑ Brink, 651

- 1 2 Magill, 272

- ↑ Hourihane, 154

- ↑ Crowe; Cavalcaselle, 207

- 1 2 3 4 Brink, 645

- ↑ Messina, 6

- ↑ Messina, 3

- ↑ Januszczak, 175-76

Sources

- Bologna, Ferdinando. "The Crowning Disc of a Duecento 'Crucifixion' and Other Points Relevant to Duccio's Relationship to Cimabue". The Burlington Magazine, Volume 125, No. 963, June 1983

- Brink, Joel. "Carpentry and Symmetry in Cimabue's Santa Croce Crucifix". The Burlington Magazine, Volume 120, No. 907, October 1978

- Cecchi, Alessandro. In: The Uffizi: History of Italian Painting. Cologne: Taschen, 2000. ISBN 978-3-8228-5999-5

- Cole, Bruce. Italian Art, 1250–1550: The Relation of Renaissance Art to Life and Society. New York: Harper & Row, 1987 ISBN 978-0-06-430162-6

- Chiellini, Monica. Cimabue. London: Scala Books, 1988. ISBN 978-0-935748-90-1

- Crowe, Joseph Archer; Cavalcaselle, Giovanni Battista. "A History of Painting in Italy, Umbria, Florence and Sienna, from the Second to the Sixteenth Century". London: J. Murray, 1903

- Emmerson, Richard. Key Figures in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. London: Routledge, 2006. ISBN 978-0-415-97385-4

- Farthing, Stephen. 1000 Paintings You Must See Before You Die. London: Cassell Illustrated, 2011. ISBN 978-1-84403-704-9

- Gibbs, Robert. "Cimabue". Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press.

- Hourihane, Colum. The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0-19-539536-5

- Jacks, Philip (ed). In: Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Modern Library, 2007. ASIN: B000XU4UR6

- Januszczak, Waldemar. Sayonara, Michelangelo: The Sistine Chapel Restored and Repackaged. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1990 ISBN 978-0-201-52395-9

- Kleinhenz, Christopher (ed). Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Volume I: A-K. New York; London: Routledge, 2003. ISBN 978-0-415-93930-0

- Magill, Frank. The Middle Ages: Dictionary of World Biography, Volume 2: Middle Ages Vol 2. London: Routledge, 1998. ISBN 978-1-57958-041-4

- Messina, Isaac, "A New Approach to the Restoration of Cimabue's Santa Croce Crucifix". New York: Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects, 2014

- Osborne, Harold (ed). The Oxford Companion to Art. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970. ISBN 978-0-19-866107-8

- Paoletti, John; Radke, Gary M. Art in Renaissance Italy. London: Laurence King, 2005. ISBN 978-1-85669-439-1

- Sylvester, David. Interviews with Francis Bacon. London: Pantheon Books, 1975. ISBN 978-0-394-49763-1

- Thompson, Nancy. "The Franciscans and the True Cross: The Decoration of the Cappella Maggiore of Santa Croce in Florence". Gesta, Volume 43, No. 1, 2004

- Viladesau, Richard. The Beauty of the Cross: The Passion of Christ in Theology and the Arts, from the Catacombs to the Eve of the Renaissance. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-19-518811-0