Spectacled caiman

| Spectacled caiman | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| on Tobago | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | Crocodylomorpha |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Alligatoridae |

| Genus: | Caiman |

| Species: | C. crocodilus |

| Binomial name | |

| Caiman crocodilus (Linnaeus, 1758 [originally Lacerta]) | |

| |

| Map of caiman distribution | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Species synonymy

| |

The spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus), also known as the white caiman or common caiman, is a crocodilian reptile found in much of Central and South America.[1] It lives in a range of lowland wetland and riverine habitat types, and can tolerate salt water, as well as fresh; due in part to this adaptability, it is the most common of all crocodilian species.

Characteristics

The spectacled caiman is a Small and medium-sized crocodilian. Males of the species are generally 1.8 to 2 m (5.9 to 6.6 ft), while females are smaller, usually around 1.2–1.4 m (3.9–4.6 ft). The body mass of most adults is between 7 and 40 kg (15 and 88 lb). The maximum reported size for the species is 2.5 m (8.2 ft), with a body mass of 58 kg (128 lb) but they can growing up to 3 m in length potentially. The largest female was reportedly 1.61 m (5.3 ft) long and weighed 20 kg (44 lb). Caimans from the Venezuelan llanos are reportedly larger-bodied than specimens from Mexico.[2] The species' common name comes from a bony ridge between the eyes, which gives the appearance of a pair of spectacles.[2] Overall a typical crocodilian gray-green coloration, this species has been known to change color. During colder weather, the black pigment, found within their skin cells, will expand, making them appear darker.[3]

Biology and behavior

Hunting and diet

Caimans eat a variety of invertebrates such as insects, crustaceans, and mollusks. Larger caimans eat fish and water snails.[4] Older animals are capable of taking larger, mammalian prey (e.g. wild pigs). As conditions become drier, caimans stop feeding. In areas where this species has become depleted, fish populations have also shown a decline. Until recently, C. crocodilus was thought to overeat the fish and snail populations.[4] Some suggest they control piranha populations. However, piranhas have not been found to be a normal diet component.[4] The yacare caiman does demonstrate this particular dietary preference. In reality, C. crocodilus likely is very much a generalist and adaptive predator, given its ecological success.

Reproduction

The spectacled caiman reaches sexual maturity from four to seven years old. Usually, the more dominant individuals mature more quickly.[2] They gather and mate during the dry season. After mating season ends, the females build nests out of dense vegetation. The size of the nest varies depending on the resources available to the female.[5] Each female can lay up to 40 eggs.[3] The larger females have recently been found to lay larger eggs than smaller females lay.[6] Most caimans nest during the wet season. Seeing a caiman nest during any winter months is very unusual; the temperature is too low for the eggs.[5]

Temperature is important to the developing eggs, so females build their nests in a way that insulates them from extreme temperature changes. The nests are made of vegetation; as the vegetation decays, the nests produce heat which can keep the eggs about 5 °C warmer than if they were insulated by mud alone.[5] Heat not only incubates the eggs, but also determines the sex of the developing caimans. When the temperature inside the nest is about 31 °C or lower, the caimans become male. However, when the temperature is about 32 °C or higher, they become female.[7] Young caimans do not hatch with the dark-green colouring of their parents. They are yellow with black spots. This colouration eventually fades away.[2]

Spectacled caimans have strongly protective maternal behaviour. They raise their young in crèches, one female taking care of her own, as well as several others' offspring.[8] They take care of their young for the first two to four months after the eggs hatch, the time it takes for the floods of the wet season to subside.[5]

Conservation

This species benefits from overhunting of competitive species which occupy the same home range. This allows them access to resources normally lost to these other species.[2] Their skin is not wanted for leather production because it contains osteoderms. The only skin on their bodies which does not contain osteoderms are their sides. Therefore, hunting of this species is relatively low.[2] In most countries, hunting this species is legal. Venezuela permits hunting every fall, providing the number of kills does not exceed 150,000 for that season.[3] The skin that is salvageable will be harvested. It is commonly found in the American sometimes mislabeled as Alligator mississippiensis.[2]

About four million spectacled caimans are found in Venezuela. Recent surveys show the population is expected to continue to increase.[3] This is an example of how well the species is able to adapt.[2] However, it is difficult to determine how well the species is doing on a global scale, since populations are not doing well in other countries, including Peru[3] and El Salvador. Despite being commonly mistaken as this species, the incredibly large population of caimans living within the Brazilian pantanal are a separate species, the yacare caiman. More up-to-date surveys are required for clarification, and to examine the interactions between the different subspecies. Further taxonomic work would make control measures easier to implement, as identification of different subspecies currently can be difficult. The major threat to this species and its subspecies is currently illegal hunting. Smuggling rings operating from Thailand and Singapore are extremely damaging to individual populations, and greater control measures and more effective legislation are needed.

According to the Crocodilian Species List:[9] "The subspecies C. c. apaporiensis is under severe threat in Colombia. Feral populations of C. crocodilus are creating problems for other species of crocodilians and native wildlife, however. These populations have become established in three countries. The introduced population in Cuba is thought to have been primarily responsible for the dramatic decline and probable disappearance of Crocodylus rhombifer from the Isla de la Juventud."[2]

Conservation programs are used in many countries. The most common form of conservation is the use of cropping, or manually reducing the numbers of several wild, and abundant, species. Long-term effects have yet to be discovered; more surveys have been recommended. Also, farming or ranching programs seem to be more expensive and possibly less effective.[2] Invasive populations have become established in Florida.[10]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caiman crocodilus. |

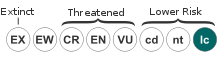

- ↑ Crocodile Specialist Group (1996). "Caiman crocodilus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2006. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 6 May 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Britton, A. Caiman Crocodilus (Linnaeus, 1758). Crocodilian Species List.http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/cnhc/csp_ccro.htm.2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alderton, D. Common Caiman Caiman crocodilus. Crocodiles and Alligators of the World. Facts on File, Inc. 1998. 131-135.

- 1 2 3 Ross,C.A. and Magnusson, W. E. "Living Crocodilians."Crocodiles and Alligators. Ross, C.A. Garnett, S. Dr. Facts on File, New York. 1989.58-73.

- 1 2 3 4 Magnusson, W.E. Vliet, K.A. Pooley, A.C. and Whitaker, R. "Reproduction." Crocodiles and Alligators. Ross, C.A. Garnett, S. Dr. Facts on File, New York. 1989. 118-124.

- ↑ Campos, Z. Magnusson, W. Saniotti, T. and Coutinho,M. "Reproductive trade-offs in Caiman crocodilus and Caiman crocodilus yacare: implications for size related management quotas"Herpetological Journal.Vol. 18 Issue 2. April 2008. 91.

- ↑ Lang, J.W. "Sex Determination."Crocodiles and Alligators. Ross, C.A. Garnett, S. Dr. Facts on File, New York. 1989. 120.

- ↑ Life in Cold Blood: Giants

- ↑ Crocodilian species list from the Florida Museum of Natural History

- ↑ United States Geological Survey. Common Caiman: Fact Sheet.http://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/factsheet.aspx?SpeciesID=222